There is no shop anywhere where one can buy friendship.

—Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, 1943

Gossiping Sparrows, by Zhang Ruoai, eighteenth century. Cleveland Museum of Art.

Tim Burton’s Ed Wood is among the most touching, incisive, and thrillingly peculiar testaments to the power of friendship. Filmed in black and white, the 1994 biopic celebrates the way that a friend can persuade us that we are not alone in the world, the way that a friend can embolden us to become the person we were born to be, to do the things that, we believe, we were put on earth to accomplish. In the case of Edward D. Wood Jr. (played by Johnny Depp), that consuming ambition—that foundational desire—was to write and direct low-budget, crude, unintentionally hilarious 1950s B-movies (Plan 9 from Outer Space, Bride of the Monster) while wearing a blond wig, high heels, and his girlfriend’s angora sweaters.

In Burton’s version, the would-be auteur has an unsurprisingly hard time finding someone who can comprehend, let alone share, his dream until he is befriended by Bela Lugosi: lonely, poor, elderly, long past the end of his career as a star of Hollywood horror films, most famously Dracula. After their meeting—appropriately, in a funeral parlor—and despite the difference in their ages and backgrounds, the two men grow to need and love each other.

Brilliantly played by Martin Landau, Lugosi not only acts in Wood’s movies and gives each scene his all—at one point he jumps into the water to wrestle a broken mechanical octopus—but also encourages Wood’s belief in their vocation: the higher purpose of their art. Their eccentricities complement each other’s, and their dedication to the magic (in this case, the rough magic) of cinema makes their eyes gleam with the same lunatic visionary light. Wood could never do what he does without Lugosi, and their friendship literally keeps Lugosi alive.

This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly illuminates the mystery of friendship, a relationship that, potentially offering both pleasure and pain, sustenance and suffering, so closely resembles the mystery of love. The writers included here address the ways in which friendship can bring out our most and least admirable qualities and the way it allows us to demonstrate our unselfishness and nobility, or, conversely, our faithlessness, smallness, and cruelty. These writers consider the range and complexity of friendships, from the most inspiriting and enduring to the more fragile, unhelpful, and even poisonous.

Aristotle tells us much of what we need to know about friendship, its requirements and rewards: “Perfect friendship is the friendship of men who are good and alike in virtue; for these wish well alike to each other qua good, and they are good in themselves…This kind of friendship, then, is perfect both in respect of duration and in all other respects. In it, each gets from each in all respects the same as, or something like what, he gives. This is what ought to happen between friends.” Such friendship can blunt the sharp, hotly defended borders between one person and another. In the marvelous tale told by Chrétien de Troyes, two knights—Yvain and Gawain—fight bitterly until they identify themselves and recognize the friend beneath the ironclad disguise of medieval armor. Both offer to give up the victory for which they fought so hard, but self-sacrifice and generosity are so natural to their friendship that defeat at the hands of a friend hardly registers as a loss.

Francis Bacon tells us what friendship, in its highest form, can provide: “A principal fruit of friendship is the ease and discharge of the fullness and swellings of the heart which passions of all kinds do cause and induce.” In

The Princess of Clèves, the French queen’s joy at being able to tell a friend the truth sets off a volcanic explosion of suppressed and desperate confidences about the king’s lying mistress, the vain crown princess, the rude and hateful courtiers. Cervantes suggests that the friendship between a married man and a single friend can be a risky business, but at least the discerning friend can alert the husband to the overlooked flaws of a too dearly beloved wife.

Our ability to speak openly to a friend functions as a safety valve, beneficial to the heart even as the mind is sharpened by a friend’s understanding and sage advice. A friend can tell us what we need to hear, truths that might not have occurred to us on our own. Passing the victim of a disastrous, self-inflicted fashion choice, my daughter-in-law will sometimes whisper, “Doesn’t that person have any friends?” It’s the kind of remark that stays with you.

Writing in 1750, Eliza Haywood finds friendship to be purer and less troublesome than love: “Its sole aim being to make the happiness of others. No jealous pangs, no anxious cares disturb the tranquility of its ideas…How then can anyone pretend that such a celestial intercourse is not infinitely to be preferred to all the gross delights of a passion?” Friends provide the ease of company, of secrets shared. The two young men in Dinaw Mengestu’s All Our Names, who are poor, ambitious students at a politically restive African university, fall into step “the way two stray dogs find themselves linked by treading the same path every day in search of food and companionship.” C.S. Lewis captures the instant when friendship begins, “the moment when one man says to another, ‘What! You too? I thought that no one but myself…’ ”

Sherlock Holmes initiates his friendship with John Watson by appearing to read his mind (“You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive”) and in exulting in a new method for identifying bloodstains—an outburst cleverly guaranteed to distinguish a potential friend from a stranger nervously looking for the exit. Holmes has a laundry list of necessities for a friendship; it’s like a job application, or an exam, and Watson gets every answer right.

Friendship at its most elevated—unselfish, thoughtful, egalitarian—should ideally serve as the model for a larger social good, as a standard of how we, as a society, ought to treat one another. If we were to see every suffering as the suffering of a friend, every loss, every deprivation and injustice as something befalling a friend, wouldn’t that radically rearrange—and humanize—the social order? So far it hasn’t happened; likely we will never know.

With characteristic common sense,

Alexis de Tocqueville observes that while democracy should, in theory, encourage friendships and a social life across class divisions, the rich tend to party with the rich, the poor with the poor. A half century later, Peter Kropotkin observed something similar in the way that mutual aid tended to flow rather narrowly within the limited channels of one’s own social class. But he greatly admired the strength and ubiquity of mutual aid among the poor. He was especially struck by the alliance of the mothers: “In a thousand small ways, the mothers support each other and bestow their care upon children that are not their own…They cannot stand the sight of a hungry child; they must feed it, and so they do.” Modern readers will notice how accurately Kropotkin is describing the women in Grace Paley’s stories. Their common ground is the playground. They know one another’s kids. They feed them, pick them up from school. The friends stick around longer than the husbands and boyfriends.

In Paley’s “Living,” a woman remembers the experiences she shared with a friend who has died: “We drove the kids up every damn rock in Central Park. On Easter Sunday, we pasted white doves on blue posters and prayed on Eighth Street for peace. Then we were tired and screamed at the kids. The boys were babies. For a joke we stapled their snowsuits to our skirts, and in a rage of slavery every Saturday for weeks, we marched across the bridges that connect Manhattan to the world.”

In case we wonder why not all of us have healthy, sustaining, lifelong friendships, this issue offers some answers to the riddle of why and how friendships, begun in such pleasure and good faith, can derail so catastrophically.

Obviously, one threat to friendship is death, the built-in drawback to any cherished human connection. Composed in the second millennium, Gilgamesh’s haunting lament for his friend Enkidu makes us realize how little grief and mourning have changed in four thousand years. Saint Augustine is nearly destroyed by sorrow over the death of a friend: “I hated everything, because nothing had him in it, and nothing could now say to me, ‘Look, he’s coming.’ ”

The moral, as always, is that if you’re afraid of losing friends, it’s probably better not to have any. Deborah Eisenberg provides a helpful list of considerations:

Even if “your friend” does something annoying, or if you and “your friend” decide that you hate each other, or if “your friend” moves away and you lose each other’s address, you still have a friendship, and although it can change shape, look different in different lights, become an embarrassment or an encumbrance or a sorrow, it can’t simply cease to have existed…so attempts to disavow or destroy it will not merely constitute betrayals of friendship but, more practically, are bound to be fruitless, causing damage only to the humans involved rather than to that gummy jungle (friendship) in which those humans have entrapped themselves, so if sometime in the future you’re not going to want to have been a particular person’s friend, or if you’re not going to want to have had the particular friendship…then don’t be friends with that person at all, don’t talk to that person, don’t go anywhere near that person, because as soon as you start to see something from that person’s point of view (which, inevitably, will be as soon as you stand next to that person) common ground is sure to slide under your feet.

For all the natural adhesiveness Eisenberg attributes to friendship, plenty of things short of death can cause friendship’s “gummy jungle” to wither and vanish. In The Ring of the Dove, Ibn Hazm discusses a friendship gone wrong: “I once had a friend whose intentions toward me became ignoble…When his feelings toward me changed, he divulged all that he had got to know about me.” In the fourteenth century, Yoshida Kenko complains about the sort of person we’ve all met, the friend whose idea of conversation, after an absence, is the protracted résumé update: “How boring it is when you meet a man after a long separation, and he insists on relating at interminable length everything that has happened to him in the meantime.”

Celia Paul’s memoir confirms

Samuel Johnson’s warning about the way that competitiveness can harm a friendship. “Friendship,” writes Johnson, “is often destroyed by opposition of interest, not only by the ponderous and visible interest which the desire of wealth and greatness forms and maintains but by a thousand secret and slight competitions, scarcely known to the mind upon which they operate.”

Johnson ended his own long and profoundly important friendship with Hester Thrale with a curt, ferociously dismissive letter. He was responding to the news that the widowed Thrale planned to remarry, and to her children’s Italian singing teacher: “If I interpret your letter right, you are ignominiously married; if it is yet undone, let us once more talk together. If you have abandoned your children and your religion, God forgive your wickedness; if you have forfeited your fame and your country, may your folly do no further mischief.”

The friendship between Johnson and Thrale was likely one of those alliances, in literature and life, eroded by possessiveness, romantic love, and sex, even when these impulses are fiercely sublimated. In Anton Chekhov’s story “About Love” and Gustave Flaubert’s novel Sentimental Education, male friendships are undermined by the fact that both men love the same woman. In his Paris memoir, A Moveable Feast, Ernest Hemingway neglects to describe how the friendship between his then wife, Hadley, and her best friend Pauline fared after he succumbed to the lure of what he calls “the other thing” and left the wife for the friend.

Illustration of a scene from Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji, by Ryujo, 1594. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Mary and James G. Wallach Foundation Gift, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2020.

Seneca considers the doomed friendship formed for any but the purest motives, the pretend friendships based largely on social climbing and business: “Anyone thinking of his own interests and seeking out friendship with this in view is making a great mistake. Things will end as they began; he has secured a friend who is going to come to his aid if captivity threatens: at the first clank of a chain, that friend will disappear. These are what are commonly called fair-weather friendships.”

Friendships can die quiet deaths. In a remarkable passage, written with Flaubert’s dazzling attention to observed detail, we tag along with

Bouvard and Pécuchet—close friends who agree on everything and share an easy, enviable camaraderie, who both love antique shops and try hard to like the paintings of Raphael—on a visit to a natural history museum: “They viewed the stuffed quadrupeds with amazement, the butterflies with delight, and the metals with indifference; the fossils made them dream…They examined the hothouses through the glass and groaned at the thought that all these leaves distilled poisons.” Who is having this thought? They both are.

Ironically, the glories of their friendship sensitize them to the less than glorious realities of daily life, and they gradually assume each other’s least appealing traits: “Formerly they had been almost happy, but their occupation humiliated them since they had begun to set a higher value on themselves, and their disgust increased while they were mutually glorifying and spoiling each other. Pécuchet contracted Bouvard’s bluntness, and Bouvard assumed a little of Pécuchet’s moroseness.”

With so many examples of the fragility of friendship, it seems all the more improbable and impressive that long friendships survive. Seneca was right when he called friendship a talent. Like any talent, it’s a gift. Some people have a gift for friendship; some don’t. Is it nature or nurture? No one knows.

My mother had the widest range of friends of anyone I have known: her close pals included a New York state trooper, a fashion industry CEO, fellow doctors, her secretary, a taxi driver, her dry cleaner’s extended family. When she died, at eighty-nine, she still had three friends from childhood. All four women grew up on the Lower East Side, first-generation American girls: stylish, ambitious, pretty. Since then they had gone on to lead very different lives. I often wondered why they remained so close. What did they have in common? I’d overheard them complaining about their kids, but was that enough? Gradually I realized that what they shared was increasing, year by year. What they had in common was time itself, memory and shared experience. The glue of four whole lifetimes connected four octogenarians who had known one another’s grandparents.

Of my friends, I am the only one I have left.

—Terence, 161 BCAmong the things that would seem to stack the odds against long friendships is the fact that every lifelong friendship isn’t one relationship but a succession of serial friendships. The highly charged alliances and bitter breakups of thirteen-year-olds are very unlike the steadier and more dependable friendships those teenagers will form in adulthood. I cannot imagine how Emily Dickinson’s brilliant “We Talked as Girls Do” escaped me until now, proving again that anything I imagine I know about her work is an underestimation. Why should it surprise me that a poem by the (intermittently) reclusive Dickinson should evoke the heady, hyperventilating froth of a group of girls?

The stories of the Argentinian Mariana Enriquez remind us that nothing invigorates young people’s friendship more than the discovery of a common enemy, whether it be a know-it-all older friend or the owner of a hotel that was a police academy during the military dictatorship. A section from Mary McCarthy’s The Group watches a group of young women take stock, adjust, and realign their loyalties in response to new information about one of their friends.

If Ed Wood is a paradigm of the positive benefits of friendship, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (both the book and the excellent film) gives us the opposite extreme. The homicidal poison released inside the twisted psyches of Perry Smith and Dick Hickock was an alchemical by-product of their friendship. They would never have murdered the Clutter family had they never met.

If friendship can bring us contentment and virtue, friendship can also function as a laboratory for the distillation of evil and ill will. Étienne de La Boétie’s description of the way in which wicked individuals form close alliances reminds us of the tyrants—Hitler, Stalin, any number of contemporary rulers—who surround themselves with greedy, malevolent courtiers who applaud their leader’s worst attributes and urge them on to commit ever more odious crimes: “There can be no friendship where there is cruelty, where there is disloyalty, where there is injustice. And in places where the wicked gather, there is conspiracy only, not companionship; these have no affection for one another; fear alone holds them together; they are not friends, they are merely accomplices.”

C.S. Lewis could be writing about Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, or about Hitler and Speer, Stalin and Beria, when he notes that the delights of meeting a kindred spirit are “no less delightful when we first met someone who shared with us a secret evil…Friendship (as the ancients saw) can be a school of virtue, but also (as they did not see) a school of vice. It is ambivalent. It makes good men better and bad men worse.” The danger, according to Lewis, lies in the way that friendship can make us blind and deaf to the world, convinced of the superiority of our insular circle—and of the inferiority of anyone who doesn’t belong, concluding, “Thus, like an aristocracy, it can create around it a vacuum across which no voice will carry.”

Even given the possibility that our friend will bore or betray us, even given the certainty that our friend will die, even given the chance, however slight, that we and our friends will become embroiled in an evil conspiracy or cabal, most people, given the choice, would rather have friends than not. Humans are herd animals; it’s the nature of our species. One reason animals clump in groups larger than the biological family is to improve their chances of staying alive.

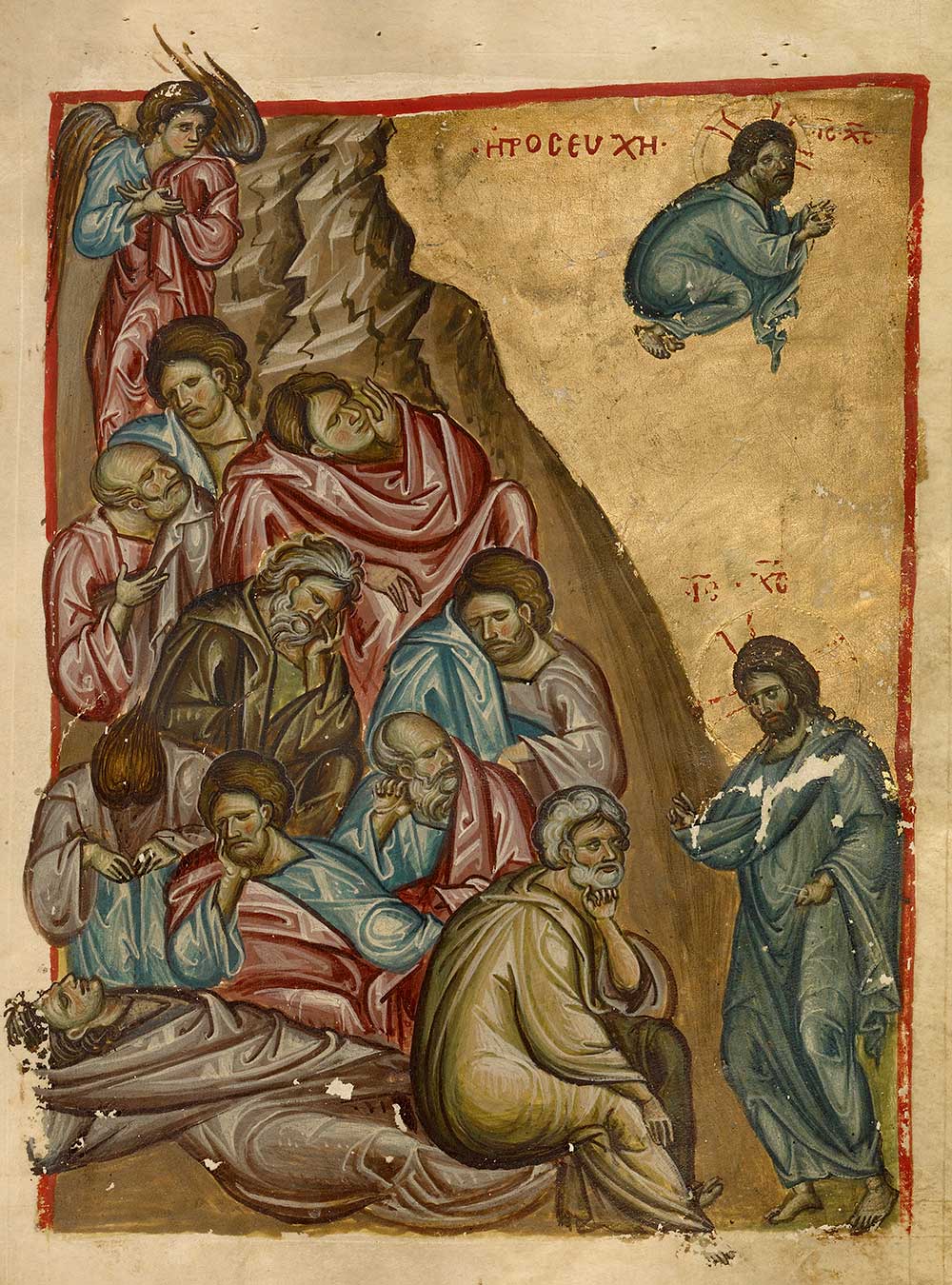

The Agony in the Garden, miniature from a thirteenth-century Byzantine Gospel. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man is, among other things, a record of how, in extremis, friendship helped Levi endure. He and his fellow prisoners work together, talk and eat their thin soup together. Levi observes their habits and calculates the chances that they will survive the horrors of the concentration camp. Among the most well-known passages is the one in which Levi, brutalized by hard labor and perpetual danger, is reminded of his humanity when he quotes Dante to a Frenchman named Jean, a friend of sorts but also an immediate superior in the ghastly hierarchy of the Lager.

A friend is saved, in a very different way, in Edward St. Aubyn’s Some Hope, the third volume of his five Patrick Melrose novels. The book ends at an English country-house party, a circus of bad behavior culminating in an act of hilarious nastiness perpetrated by Princess Margaret. But the most important thing occurs before the party begins. Over drinks, Patrick tells his friend Johnny the “most shameful and secret truth about his life”: the story of the childhood trauma that has propelled him into a spiral of self-loathing; frantically witty, caustic hostility; and manic drug addiction.

Patrick is telling his friend something he would never tell a lover, a spouse, a stranger—certainly not a blood relation. Though he feels that “the catharsis of confession [has] eluded him,” he also feels “his soul, which he could only characterize as the part of his mind that was not dominated by the need to talk, surging and writhing like a kite longing to be let go” and “a strange feeling of elation.”

If we doubt that friendship can offer us rescue and salvation, we need only remember how

Moby Dick ends. In the calm before the storm, before the looming disaster turns from probable to inevitable, Queequeg becomes desperately ill.

He orders his coffin built according to his careful specifications. But as soon as it’s completed, he recovers, claiming that the sudden memory of a chore left undone persuaded him that it wasn’t time to die. The coffin becomes a chest that the harpooner fills with his clothes and carves with images, grotesque figures and vivid patterns like those in his tattoos, hieroglyphics that offer “a complete theory of the heavens and the earth, and a mystical treatise on the art of attaining truth.”

In a brief epilogue, Ishmael tells us that, after the wreck of the Pequod, Queequeg’s coffin bobbed up from the depths to the surface of the sea. Ishmael floated on his friend’s coffin for a day and a night, surrounded by sharks, until, on the second day, he saw a ship’s sails, and he knew that he was saved.