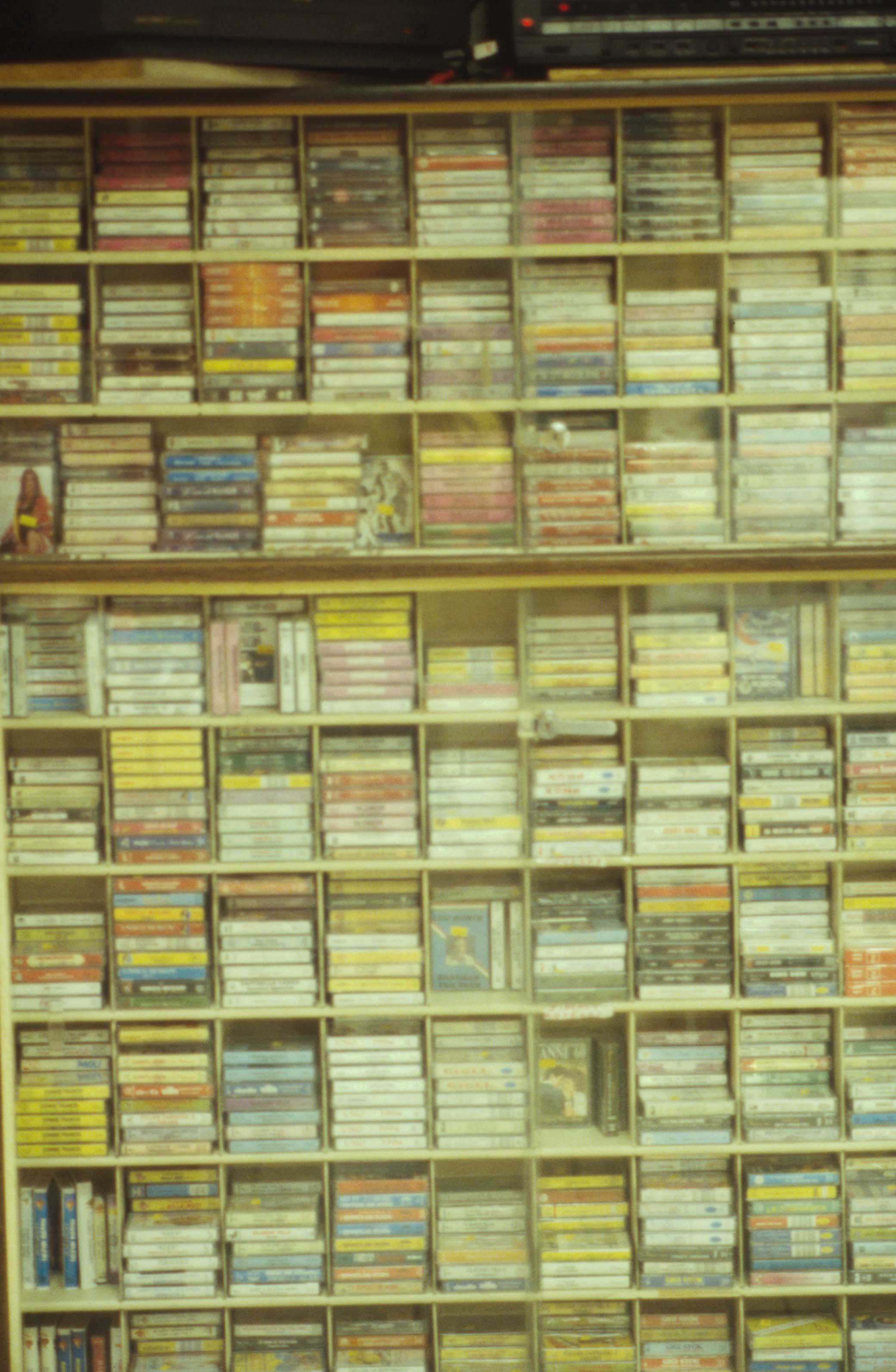

Shelf of cassette tapes, 1994. Photograph by Thomas D. Carroll. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Approaching the end of his rule, Anwar Sadat issued a series of decrees intended to curtail traffic and to combat noise pollution in Cairo. The ordinances, which officially went into effect on November 8, 1980, and remained a topic of conversation for weeks to come, outlawed the use of car horns and criminalized “blaring loudspeakers, televisions at high volumes, and impromptu tape cassette sidewalk concerts.” Courtesy of the president’s executive actions, audiocassettes, enjoyed loudly by many Egyptians in public spaces, were no longer simply a nuisance. Noisy cassette recordings were now illegal.

The noise unleashed by “vulgar” cassettes alone piqued the interest of researchers, artists, politicians, doctors, and security officials, who ostensibly strove to protect the hearing of their compatriots by pushing for certain sounds to be silenced. As early as 1978 one writer, Ragab al-Sayyid, highlighted the dangers posed by particular cassettes to Egypt’s acoustic environment and those who inhabited it. Drawing on his background as an expert at the Institute of Seas and Fisheries in Alexandria, he argued that Egypt’s soundscape, like its waters, could be polluted. To support this claim, he cited a 1977 book by R. Murray Schafer, The Tuning of the World, a seminal text in the field of sound studies that treated noise pollution as a cause for public concern.

Although al-Sayyid touches upon several sources of noise in his treatise, he arguably reserves his harshest words for shaʿbi (popular) cassette ballads and those who blasted them. On the final pages of his booklet, he singles out two types of working-class Egyptians—the “manual laborer” and the “modest seller”—who used cassette players to blare their “favorite shaʿbi singers at the highest possible volume” around the clock. To make matters worse, the extensive mobility of audiotapes, al-Sayyid points out, permitted this “clamorous music,” widely ridiculed for its “vulgar” nature, to travel from stores and street corners to crowded buses and private residences. The reach of these cassette tapes was seemingly infinite and the damage they caused to Egypt’s soundscape, the author concludes, demanded everyone’s immediate attention.

The connection drawn by al-Sayyid between noise pollution and particular cassettes was both deliberate and commonplace. At times, the subject even ascended to the highest corridors of power. In 1988 Egypt’s Upper House of Parliament convened to address the problem of pollution. During the session, one of the council’s members inquired about the steps they could take to “purify Egypt of the pollution in the world of singing.” In response to this question, which no doubt alluded to cassettes carrying shaʿbi music, Muhammad ʿAbd al-Wahhab, a fellow delegate, promised to take immediate action. Shortly after the gathering concluded, the elite artist reached out to other licensed musicians to attend to the pressing issue. At other times, the tumult induced by certain tapes caught the attention of medical professionals and security personnel. In one column published in 1986, an ear and nose doctor compared shaʿbi cassette songs blasting in taxis to “military marches” and alerted readers to the “slow death” of people’s ears in Cairo, while the director of security in the neighboring city of Giza claimed that “the chaos of voices and the chaos of tools with which to disturb” harmed both the hearing and the taste of Egyptian citizens.

Audiocassettes, in the opinion of many critics, facilitated the spread of “vulgar” sounds by making it possible for anyone to be an “artist” regardless of their training. In enabling any citizen to become a cultural producer, as opposed to a mere cultural consumer, cassettes, they claimed, lowered artistic standards and tarnished public taste. Consider, for instance, one writer’s journey into the world of “trivial” recordings. As one Arab singer confessed in the 1980s: “I expected to hear refined songs in Egypt, but I found something else entirely. I was struck by the astonishing number of singers and songs that constantly arose.” “Everyone who enjoys his voice sings,” she elaborated, “and issues a collection of new songs every two months.” By empowering “everyone” to become a performer, cassette technology, critics repeatedly claimed, bred only “chaos” and elevated voices that did not deserve to be broadcast.

As audiotapes gained ground in Egypt, the number of cassette companies rose at an astonishing rate. According to one estimate, there existed twenty well-known labels prior to 1975. By 1987 that number had skyrocketed to 365 ventures, only to climb again three years later to around five hundred businesses. Egyptians with little to no experience in the recording industry or in creating cultural productions of any kind ran a large number of these entities.

Discussions of suspect tapes in the press often censured lower- to middle-class citizens for fancying themselves as cultural producers. One journalist, for instance, attributed the proliferation of cassettes that corrupted taste to “street peddlers,” “repeat offenders,” and skilled workers who launched recording labels with the cash they acquired from the infitah, Sadat’s economic opening. A fellow reporter singled out plumbers, butchers, and cigarette sellers for creating works of art that were highly profitable and “incompatible with public taste,” and that posed a greater danger to citizens than cocaine. Still others occasionally faulted their nonelite compatriots for wielding their newfound financial influence to corrupt established artists. A professor of psychiatry and neurology at a leading medical school in Cairo argued that “trivial” tapes resulted from sweeping social changes in the 1970s and the 1980s that empowered a new parasitical class of “uneducated” Egyptians. “Seduced by money,” the doctor bewailed, “famous writers and composers drifted, and took to writing and composing for a class intruding on art without any study or mere familiarity.” In the course of attacking working-class Egyptians for producing cassettes, local critics portrayed themselves as “educated” and “refined” in relation to their “ignorant” and “crass” compatriots. At the same time, those driving these discussions did not simply differentiate themselves from those they condemned. More importantly, they argued that ordinary people had no business making Egyptian culture.

Egypt’s minister of culture from 1985 to 1987, Dr. Ahmad Haykal, once exclaimed, “Art without obligation is like a river without banks; in the end it leads to drowning.” According to him, those responsible for submerging Egyptians with purposeless, “vulgar” art committed two sins. They shirked their obligation to protect the values, morals, and taste of their compatriots, and they preyed upon Egypt’s “climate of freedom” and Sadat’s economic opening “to introduce cheap laughter they called art.” For Haykal, “vulgar” plays, films, and cassettes were appalling because they failed to fulfill one of culture’s primary objectives: crafting model citizens. Indeed, such works ran counter to the very definition of “culture” he espoused. “Culture is not an amusement,” Haykal once asserted, “culture is not an empty diversion. Culture is not a mockery. Culture is not only art. Culture, rather, is refined art.”

Throughout the mid- to late twentieth century, public culture (al-thaqafa al-jamahiriyya) was more than an idea in modern Egypt; it was a state-engineered program charged with erasing “cultural illiteracy.” The initiative Public Culture came into existence in 1966 at the hands of Tharwat ʿUkasha, a skilled politician who established several new sites linking culture and the state during his eight-year tenure as minister of culture (1958–62, 1966–70). Officially one of ʿUkasha’s creations, Public Culture drew inspiration from earlier programs connecting culture, the state, and subject formation, including the Peoples University (founded in 1945), Culture Centers (founded in 1948), and Culture Palaces (founded in 1960). The first director of Public Culture, Saʿd Kamil, was a prominent intellectual of the Egyptian left. Once appointed, he wasted little time in selecting elite men and women to relocate from Cairo to direct culture palaces, to set up culture houses and clubs, and to oversee culture caravans across Egypt. The objectives of these apparatuses were essentially twofold: to educate and elevate the taste of ordinary Egyptians and to build stronger ties between the capital and its peripheries. The foundation of both aims was a shared national culture, manufactured, distributed, and sanctioned by the government.

The success of the Public Culture program is subject to debate, but what cannot be disputed is the centrality of music to its mission. State officials working for the venture established numerous ensembles, while musical plays, recitals, and competitions took place in government establishments where guests encountered select records and cassettes in “listening clubs.” According to one publication, Public Culture held more than six thousand musical events between 1971 and 1980 that catered to an estimated three million people. Published by a state entity, these statistics should be viewed with a grain of salt. But it is beyond any doubt that music was an indispensable instrument in the state’s attempts to fashion “enlightened” Egyptians. Not all music, however, contributed to these efforts. Songs considered “tasteless” by those on the government’s payroll had no role to play in creating “cultured” citizens. Refined art exclusively advanced this task, which “vulgar” audiotapes only jeopardized. In its mission to forge “cultured” Egyptians, Public Culture was not alone. A second mechanism lent welcomed support.

State-controlled Egyptian radio placed a premium on molding model citizens. To ensure that only the “right” sounds reached the public’s ears, radio officials relied on a system of checks and balances. Two screening committees formed the foundation of this infrastructure. The first, known as the Text Committee (Lajnat al-Nusus), decided whether the radio should record numbers still being developed. If its members approved of a tune, the song entered production. A second panel, the Listening Committee (Lajnat al-Istimaʿ), determined whether recorded songs should be broadcast. If the body’s artists, broadcasters, and sound engineers endorsed a ballad, it was left to the discretion of stations to play it. Channels did not promote everything that came their way.

Radio administrators took pride in the selectivity their system inspired and the high artistic standards it allegedly upheld. And when the medium’s criteria for choosing tracks became too loose, representatives vowed to tighten them. In 1983, for example, the Listening Committee revisited its rules for approving songs. Going forward, one magazine noted, its members would only permit numbers they hailed as a “contribution” to “the world of singing.” From the perspective of officials, those capable of making such a “contribution” were limited.

According to Ibrahim al-Musbah, who oversaw musical works for the Radio and Television Union in the early 1980s, only ten poets out of five thousand writers could create proper songs. “Crass” audiotapes obstructed the efforts of radio personnel to fashion “cultured” Egyptians, and the platform’s guardians did not hesitate to censure “vulgar songs that spread in brisk cassette markets” in the press.

Excerpted from Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt by Andrew Simon, published by Stanford University Press. © 2022 by Andrew Simon. All Rights Reserved.