A statue of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on display at the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum, Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images.

My guide did not want to talk about police brutality. “People who pay their money for the museum come here for the museum. Freddie Gray is not a topic to discuss here. We’re trying to get people’s minds off Freddie Gray.”

A soft-spoken, cautious man, Eric Cherry is the facilities manager, computer technician, educator, and—when nudged into the role—press officer of Baltimore’s National Great Blacks in Wax Museum. Two weeks before my visit to the museum, in May 2015, Freddie Gray died in the custody of the Baltimore Police Department.

“Some people from out of town were scared,” said Cherry. “We tried to assure them the unrest was more in the northwest quarter, not northeast.”

While Baltimore’s citizens were rising in grief and protest, forty schools canceled their tours of the museum in a single day. The galleries had stood empty until my arrival.

“I still consider this place the safest place to be,” Cherry said as we circled the block. It was a sunny morning in the Oliver neighborhood, on a quiet street of vacant townhouses all owned by the museum.

Cherry’s phone rang: the first school bus since April had broken down en route from New York and would be an hour late. With no immediate claims on his attention, he walked me into the museum’s dimly lit galleries, which smelled of wood, fabric, and beeswax; another employee was delicately Windexing Harriet Tubman. The song “Let My People Go” and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech played simultaneously on opposite sides of the gallery. The air felt stuffy and too warm, but in the close, familiar confines of the exhibits, Cherry grew vivacious.

“If you’re here, it’s my job to educate you, no matter how rowdy or quiet you get. You can talk to me, ask me questions. I’m the only shy one here, so if I can talk, so can you.”

He recounted dialogues with visitors from around the world, their questions, their love of the taxidermied polar bear menacing an apprehensive Matthew Henson, the black navigator who first reached the spot Robert Peary would later claim as the North Pole.

Great Blacks in Wax spans the history of the African diaspora, from Nefertiti to the uncannily lifelike figure of President Obama. Rosa Parks stands stalwart before a bus; Marcus Garvey sits enthroned; Malcolm X wears a suit “donated by Fashann,” according to the placard. Nat Turner loads a rifle; Zora Neale Hurston, laughing, enlivens a study date with Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, and James Baldwin; and, in a revisionary tribute, Mae Jemison, who became the first black woman in space in 1992, operates the shuttle beside Ronald McNair, who was killed onboard Challenger in 1986. Future inductees may include Don Cornelius and Maya Angelou.

“I’m almost positive Maya Angelou gets in here,” said Cherry. “Whitney Houston I don’t know about. Every day, people come here and ask, ‘Where’s Michael Jackson?’ But his heirs haven’t given us consent. You need to file consent to show a wax figure of somebody.”

We move to the political wing. “Some people feel uncomfortable, because they don’t know the person they’re looking at, so I bring them here,” Cherry said. “Everybody knows Thurgood Marshall. Everybody knows Barack Obama.” Shirley Chisholm and Mary McLeod Bethune are here, alongside another new commission, Mahalia Jackson. “We wanted to put her with Billie Holliday in the music exhibit, but there’s no space. We have figures in storage there’s no room for yet.”

“Who?” I imagined them confined, staring, smiling.

“Colin Powell. We got Colin Powell in storage.”

Regular visitors enter the exhibition from the lobby through a heavy wooden door. Once their eyes have adjusted to the dark, they see a shackled man being force-fed by slavers. Another wears an iron punishment mask. To the left, the hull of a ship bears two signs: “Enter Slave Ship Here” and “President Obama Exhibit Up the Stairs.”

I followed Cherry downstairs into deeper darkness. In the hold, chained wax figures were crammed into the berths. Sailors branded or prepared to rape enslaved women. A naked woman hung in wrist shackles, head thrown back, wax breasts and stomach scored with glistening, bloody gouges. A mirror ran the length of the wall. It’s Cherry’s job to bring schoolchildren down here.

“Before we leave, I say, ‘Look in the mirror. It represents where you came from. Remember how you got here. Remember where you’re going. What are you trying to do?’” When he flipped a switch, the claustrophobic hold filled with the sounds of groans, creaking timbers, and waves. “I ask them, ‘Give me one word that describes the audio.’ The kids say, ‘Pain.’ ‘Tired.’”

We listened together. Cherry told the mirror quietly, “In today’s society, you’re still being punished for things you didn’t do. And you get real sick and tired of it.”

Douglas Myers, a Baltimore writer who visited Great Blacks in Wax every February of his youth, puts it succinctly: “Wax museums are creepy.”

Wax figures are the textbook definition of the uncanny: Freud based his theory on Ernst Jentsch’s writings about the uncanniness of waxworks and automata. But centuries before Madame Tussaud cast her first freshly guillotined head, people already found wax uncannily, creepily, beautifully fleshlike: pliant, lustrous, immobile, fragrant, organic. Medieval and early modern artists sculpted wax effigies of saints and ex-votos of body parts. By the time Philippe Curtius opened his Parisian Cabinet de Cire in 1770, wax modeling had become a fashionable, aristocratic form of portraiture. His housekeeper’s daughter, Marie, inherited his collection, learned his trade, and made it her own, most famously with the death mask she had taken of Marat while he lay shriveling in his bathwater.

Marie Tussaud installed a permanent exhibition in London in 1835, but spent much of her career on the road. Most commercial waxworks of her era were either itinerant fairground displays or, later, shop mannequins. Meanwhile, the art flourished in medical schools, which collected wax specimens of diseased organs, as well as Anatomical Venuses: full-scale figures of gracefully posed sleeping women who could be bloodlessly dissected, their organs exposed and removable. These study collections served also as spectacles of curatorial pride and institutional wealth, often exhibited to the public (though admittance was usually restricted to men).

In 1882, the first self-identified wax museum, the Musée Grévin, initiated a new waxworks paradigm in the capitals of Europe and the United States: they would be institutions of bourgeois urban edification and entertainment, funded by investors and staged with glamorous costumes and luxurious props. The Musée Grévin’s founder, publisher Arthur Meyer, sought to “create a kind of plastic newspaper, where the public would find, reproduced with a scrupulous respect for nature, the personalities who, in various capacities, occupy its attention.” The Gilded Age wax palaces were new media, using celebrities and spectacles to teach visitors how to think about news, history, culture—and social and material aspirations.

The writer Alexandre Dumas, fils (whose grandmother had been enslaved in a French colony), imagined the waxworks of the Musée Grévin at nighttime “murmuring low amongst themselves, holding poses, with a stifled laugh in their stuffed lungs: ‘Now, we’re the living.’”

Amid all the upholstery and trompe l’oeil, wax museums stayed creepy. They hewed too close to the wax figures that substituted for actual corpses at the Paris Morgue when the originals had decomposed too much for public display. Wax museums competed to be the first to commemorate recently deceased celebrities. They collected authentic “relics” of the famous dead—their clothes, Marat’s bathtub, even the donated hair of the Danish royalty at the Copenhagen museum—to heighten the realism. And, of course, there was what the London press in 1846 dubbed the “chamber of horrors,” first seen at Madame Tussaud’s but widely imitated at other waxworks, including the Grévin.

These basement chambers depicted suffering, poverty, pain—sensational crimes and criminals, trials and punishments, the French Revolution and the Spanish Inquisition. Leonard Koos, a professor of French at the University of Mary Washington, has argued that the violent, prurient, and disgusting content of the chambers of horrors was entirely consistent with the museums’ bourgeois moral didacticism: Behave, and you’ll win the wealth and fame upstairs. Act up, and you’ll get hacked to pieces by a serial killer or the executioner.

The wax palaces—which went by the suggestive name Panoptikon in Germany and Scandinavia—inflicted consequences for transgressive behavior, just as the lesions and eruptions of the wax anatomical collections portrayed the just deserts of addiction and venery. Wax museums surveilled the bodies not only of the figures portrayed there but also of the spectators, uniting capitalist striving, edification, and respectability with torture, titillation, memento mori, and entertainment.

World War I, inflation, and new trends in visual culture nearly killed the wax museums, and horror films transformed them into bywords for obsolescence, monstrosity, and kitsch. Despite the artistry of Madame Tussaud’s (and the odd outlier like New Orleans’s Musée Conti), calling something a wax museum still implies that both its own existence and whatever it memorializes are anachronistic, like zoetropes and operetta.

But in twenty-first-century Baltimore, 300,000 annual visitors regard Great Blacks in Wax as a vital, relevant institution.

“I’ve brought my children, my grandchild, and big groups. It’s one of the best museums we know of. God’s spirit calls them to do what they’re doing,” said Phillip Basil Hunter, a bow-tied retired lawyer. He had come to book a guided tour for the fiftieth reunion of his high school class, the friends with whom he’d marched in the three 1965 Selma marches, the civil rights rank and file who’d been honored with the Congressional Gold Medal last spring. “We’re coming to this museum to connect with history,” said Hunter—a man who marched with both Dr. King and President Obama but wanted to talk not of them but of his father, the Reverend J.D. Hunter, who’d been instrumental in planning those marches. Even so, my suggestion of honoring him and the other foot soldiers with wax figures startled him (“I’m not sure what the museum owners would think”).

The museum was founded in 1983 by Dr. Joanne Martin and her late husband, Dr. Elmer Martin, who worked at Coppin State and Morgan State Universities, respectively. First they visited Native American heritage museums, Ellis Island, and Paris’s National des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie (incorporated into the Musée du quai Branly) “to learn how different groups of people tell their stories,” explained Martin. “There was a confidence in knowing you had a place in history.”

So why wax? After all their travels in South America, Africa, and Europe, a trip to Florida with Elmer’s grandmother (“I suggested we go to the alligator farm”) took them to Potter’s Wax Museum in St. Augustine.

“Elmer and I were just fascinated by the medium, that way of telling a story. One day, Elmer came home and said he’d been at the Library of Congress all day, looking up wax museums of African or African American history, and he’d found none. That became the spark.”

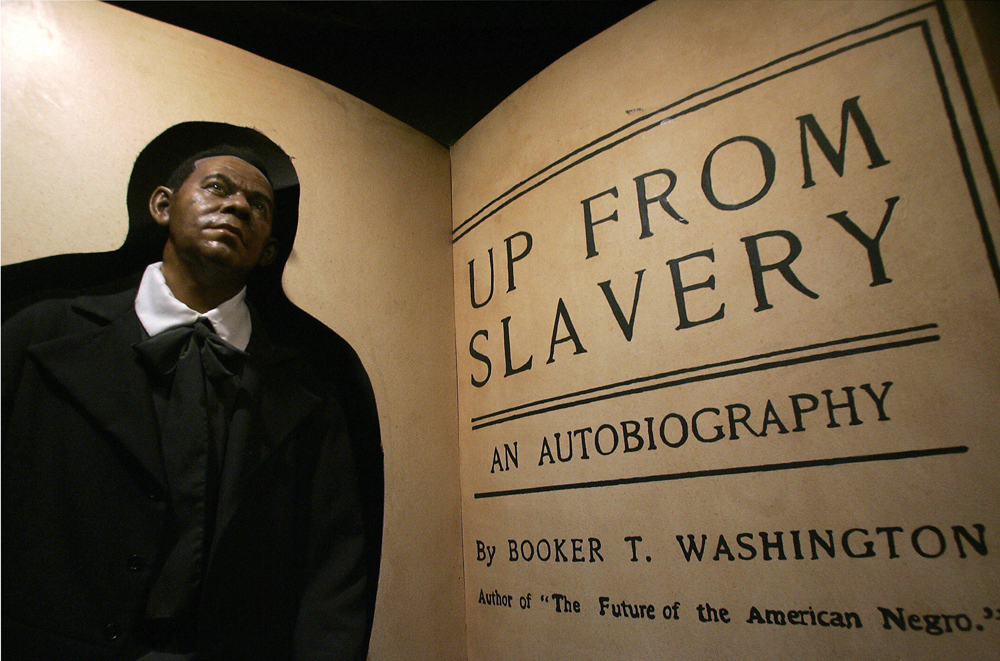

Joanne grew up in Yulee, Florida, where at school, “we had Negro history week, a little program, a few poems, then we got back to the business of ‘real’ history. We knew what George Washington looked like, but not George Washington Carver. Booker T. Washington was probably the most powerful black man of his time, but it was only with our wax figure of him that I knew what he looked like. That’s the importance of wax: it puts a face on our history.”

Great Blacks in Wax began as an itinerant exhibition packed into their Pontiac hatchback: “A cute little car with a racing stripe. We started out with four figures. We’d drive them around and set them up in schools and churches. Elmer gave us the lofty name ‘The Martins’ Wax Museum of Great Afro-Americans.’” Once, when her husband was too tired to break down an exhibit before loading it, “he had Frederick Douglass’s feet sticking out of the hatchback, and he had the nerve to get on the Beltway. The police stopped him, and he had to convince them he wasn’t carrying a body.”

They housed the figures in the guest bedroom of their basement apartment. One neighbor later told them, “I’m so glad to finally see what you and your husband are into, because we’d see you coming out of the basement with these bodies, and I’d say, ‘Look, look, look! They’re out there with those things! And they seem like such normal people!’”

The Drs. Martin used their first home down payment, her wedding ring, and personal loans to move their collection first into a storefront, then the decommissioned firehouse it occupies today.

Great Blacks in Wax makes history outside official channels, even outside the aesthetic and pedagogical aims of many other African American history museums (it finds an unlikely precedent in Curtius’s wax cabinet, which the Société Républicaine des Arts denounced in 1794 as ridiculous, counterrevolutionary charlatanism that the public dangerously preferred to state-sanctioned museums). Yet Great Blacks in Wax is also faithful to the traditions of the Gilded Age waxworks, with its dramatic tableaux (Harriet Tubman extracts a slave from his stove-chimney hiding place); mirrors (“where one can see one’s reflection with the mannequins,” per the Musée Grévin brochure); and animatronics (Henry “Box” Brown peeks from the crate in which he shipped himself to freedom). The plantation scenes evoke Moses Kimball’s Boston Museum, which in 1850 advertised waxworks “so NATURAL and LIFELIKE as to Mock Reality,” including a massacre by pirates, the evils of intemperance, “SIAMESE TWINS and their beautiful American wives,” and the “HORRORS OF SLAVERY, as exemplified by seven figures, being actual likenesses of a slave-owner, a slave-driver, and their victims.” Great Blacks makes no concessions to the past twenty years of curatorial innovations, offering no interactive or video exhibits, as though learning from the ill-fated Swedish Panoptikon, whose introduction of film repelled audiences who reckoned the new medium as shadowy and unreal compared to the narrative heft of wax.

Yet even visitors who have grown up with touchscreens respond to Great Blacks in Wax’s “realness.” At the entrance strides a life-sized elephant ridden by an exuberant Hannibal. The exhibit is old and looks shabby and chipped under the lobby’s fluorescent lighting; Hannibal lacks the detailed modeling of the new figures. But a young man visiting from North Carolina remarked, “This is pretty striking. Usually when you see pictures of Hannibal, he’s not black.” That makes all the difference. Great Blacks in Wax is real to visitors not because of visual verisimilitude, but because it insists on the value of black people’s lives and their presence throughout history. It’s about the black, not the wax.

According to Whitley London, a Temple University student visiting the museum, “African American history’s been smoothed out. You lose focus of how it was, how cruel. But this is the most impacting museum I’ve ever been to. It’s amazing, it’s face-to-face, like reading Nat Turner’s Rebellion—though that was written by a white man.”

Like its nineteenth-century precursors, Great Blacks in Wax delivers the promised Greats, but it also unflinchingly portrays violence. Contemporary visitors, like their nineteenth-century counterparts, flock to those scenes. Several raved about the slave ship; one man from Louisville, Maryland, called it “amazing and powerful—the exhibits are so real and lifelike.”

Phillip Hunter recalled his first visit: “I was awestruck to see where the slaves were packed like sardines into boats. How they had to make the journey in their own fecal matter, and if they died or were sick, they were thrown overboard, like they weren’t worth anything.”

Once, years ago, Martin asked her uncle if he had a lynching story. “He looked at me and said, ‘Oh, child, all black people got a lynching story.’” Hence, Great Blacks in Wax’s own basement chamber of horrors, unveiled in 1997: “The Struggle Against Lynching: Lessons for Today.”

The students from Far Rockaway, Queens, finally arrived and split into groups: the sixth and seventh graders with volunteers Ms. Reba and Ms. Flo, both retired teachers; the fourth and fifth graders with Martin. “Kids! I want your attention right here!” said Ms. Reba. The kids were restive after their long bus trip, and there was so much to look at, so much to photograph with their phones. They took selfies with Obama, laughed over “Box” Brown, and filed patiently through the slave ship. The little ones peered closer and closer at a diorama while their chaperone whispered, “Get back—back—” Too late: they knocked over an African sculpture. Murmurs of consternation. Cherry moved the sculpture to a safer place on the platform.

Beside the stairwell to the basement, a sign strongly warned against admitting children under twelve. A culling ensued. One eleven-year-old kicked the wall: “This trip is lame!” Another rolled his eyes and draped himself over the railing, sneaking around the turn in the stairs. Never had kids been more eager to see a museum exhibit.

Descending the stairs, the twelve-and-ups giggled, psyching themselves up for a carnival haunted house. One girl gasped, “I’m going to scream. I can’t do it. Ooh ooh ooh! All this is just…” Rounding the corner, she faced the display, which, unlike the exhibits upstairs, was starkly lit and kept behind glass. Her friends gathered around her. As the small room filled with kids, the silence deepened.

They were looking at a recreation of the 1918 lynchings of Hayes and Mary Turner. When Mary, who was eight months pregnant, protested her husband’s murder at the hands of white neighbors, the lynchers hanged her, shot her, and set her body afire with gasoline. They cut the fetus from her body and stomped on it. The figure of Mary Turner was the hardest thing to look at in the museum. Ms. Reba’s style was vigorous and no-nonsense. She narrated the Turners’ story, doing the voices of the lynchers discussing “that nigger.” The children shifted. “They smashed the baby to the ground,” she told them, pointing.

“Was she alive?” asked a girl.

“Yes, she was alive.”

Some students covered their mouths with their hands. One stood still, gaze averted from the exhibit, jaw distended in a rictus of distress, before running back upstairs.

A display of glass apothecary jars contained the wax models of genitals and other organs, suspended in what looked like alcohol or brine. They suggested a general store counter, where lynching victims’ body parts were sometimes put on display, or the moulages of the anatomical museums. Or the sacred relics of a shrine. Ms. Reba said, “In this period, many people who were black got mutilated, and their parts were put in jars, and people had parties and had fun talking about what they’d done.” Soft hisses between the children’s teeth.

After their group left, Ms. Flo brought hers, letting them explore by themselves. “I saw a movie about hanging,” whispered one boy to another, looking up at the noose dangling from the ceiling. Another kid read aloud from the list of names of five thousand lynched black Americans.

Ms. Flo showed them the photo of Emmett Till’s swollen, disfigured face. “This was in Jet magazine. I remember seeing that.” When she began Till’s story, two boys whistled: brief trills of notes, such a vivid sound, in this sixtieth anniversary year of a boy’s murder. When she told them that his lynchers never served a day in jail, nobody was surprised.

She pointed to the framed newspaper clipping about the modern-day lynching of James Byrd Jr., the Texas man tortured and murdered by three white supremacists, who chained him to the back of their pickup truck and dragged him. “This happened in June ’98.”

The kids stood on tiptoe, craning their necks to see: this recent relic was real in a different way.

A child asked, “Why did they take him?”

“Why did they take him?” Ms. Flo’s voice was gentle. “Why did they take Freddie Gray? Who can answer that? I don’t know…I don’t know.”

It was time to go. As the room cleared, one boy lingered before the Turners. He asked his teacher, “She was pregnant? And they cut out the baby?” He’d heard it the first time, but he waited for his teacher to nod. Then the boy reached out to touch the glass, lightly, with his fingertips.

Another staffer, Frazier Durham, said, “We have blinders on sometimes; we see what we want to see. But here, we tell you what’s real. I wish more museums were like this. I wish more people would talk about it.” In the lobby, five girls sat in a row, recovering from the basement. One of them chattered gaily with their teacher: an act of mercy, giving cover to her weeping friends so they had time to collect themselves. Both children and adults responded most strongly not to the greatness displayed in the museum but to the history of suffering.

“Ain’t nothing changed,” said one of a group of Maryland women. “I’m from the South; I attended segregated schools. My great-great-grandmother was a slave. In a segregated world, you think it’s different outside. But we migrated to Maryland, and it’s not.”

Her friend said of the recent Baltimore protests, “This is just a part of our history. I was telling the grandkids, when Martin Luther King was assassinated, we had the National Guards come in against the rioting then, too.”

The first woman added, “I love this museum. Many people can’t appreciate where they’re coming from and who they are. From my perspective as a senior citizen, I say things ain’t changed. From a young person’s situation”—she indicated her niece, a college student—“you can feel that maybe things can. You can learn and investigate.”

But the niece said, “Before police brutality started being so common, I thought it was different from back in the day. Then you see the brutality, and you come here, and you see it’s the same.”

Phillip Hunter, who was himself gassed by police on Bloody Sunday in 1965, said, “There should be some depiction of the unjust treatment that blacks have received at the hands of law enforcement. There’s many other instances where this is captured on video, whether Ferguson, or where a black man was fleeing and an officer just shot him seven or eight times. So there should be something in museums that shows how law enforcement has brutalized us, unfairly and unnecessarily.”

Toshiba Cherry, who dropped by to say hello to her husband (our guide), visits again and again to “look at the lynching. It explains all kinds of different things, and that’s just a smidgen of violence. There’s not enough space, not enough words to demonstrate the violence, all that went on then, all that’s still going on. When’s it going to stop? We need change. We’re losing the youth.”

Carol Jolley has worked at the museum for twenty-six years, first as a volunteer, then as an assistant to the Martins. “When they decided to do this museum, Dr. Elmer had a Little League Team in the city,” she said. “When they took team photos, one little child came to Dr. Elmer and said, ‘The photographer needs to take my picture over.’ Dr. Elmer said, ‘Why, son? It’s a beautiful picture.’ The child said, ‘They made me too black in this picture.’ And Dr. Elmer said, ‘Where? Where have we gone wrong?’ He said children needed to know their culture and history, so he decided to open a museum in a neighborhood like this. Not the Harbor. A neighborhood where we are, like this one, that we love.”

Great Blacks in Wax hosts an annual Voices of History summer street fair. In addition to working with Ms. Reba and Ms. Flo—who, Martin tells me, were “teachers and community activists and grew up during some of the times we portray”—the museum has partnered with the Baltimore YouthWorks jobs program for fifteen years to train city youth to be guides, educators, and historians in turn. The museum also hires docents pursuing degrees in museum studies: “They’re young enough that the children can make a connection, and also be in awe that someone their age could have that kind of knowledge and skill.”

The museum is seeking funding for a $75 million expansion to build a theater, garden, and café over the vacant block. Martin hopes to expand and update the galleries to welcome new audiences, supplementing the placards with audiovisual and interactive exhibits.

But as the museum aspires to become a twenty-first-century community hub, one more aspect of wax museum history bears mentioning. All the guides were good teachers, but Martin possessed a leader’s charisma, her elegant storytelling imparting information while eliciting full participation. The kids clustered around her, entranced, trying to impress her. Standing beside the figure in the punishment mask, she asked, “If you saw someone in this”—she rattled the bell rack, which was fitted to enslaved people’s necks to thwart escapes—“how would you feel?”

Hands shot up. “Sad!” “Scared!” “Terrified!”

“Why?”

One child answered, “Because…you don’t know what they’re going to do to…”

“To who?”

“You,” softly.

Martin nodded. “This is what slavery’s all about: control.”

Within minutes, the kids were pledging her an oath. “For my ancestors,” she recited, and they repeated fervently, “For my ancestors…who gave me God’s gift of life…I’m going to know a slave ship when I see one, the ones they call prisons, jails, penitentiaries, where people are taken away in chains. I’m going to know a slave seller when I see one, the ones they call drug dealers.”

The Gilded Age chambers of horrors were designed to scare people straight. At Great Blacks in Wax, right next to the lynchings of the Turners looms another horror scene: the “Blvd. of Broken Dreams”—a “drug and murder alley” where waxen addicts lie dying and a skull-faced, hoodie-clad dealer points a gun at viewers. Two separate signs read, “Now We Lynch Ourselves.” Upstairs lurks the figure of a demonic-looking boy with a needle protruding from his arm, incurring “the tears of the ancestors.”

Doug Myers grew up on Black History Month class trips to these scenes. He doesn’t mind the violence. “It should give you a visceral reaction, a disgust with how things were and hope for the future.” Nonetheless, he added, “I don’t like the shame aspect of it. Being a minority in this country, there’s enough shame manufactured without addressing context: why people sell drugs, do drugs. Minorities have to do things to survive. If you’re eight in this city, you’ll think, ‘That’s the only way I’ll get by.’ Rappers rapping about selling drugs also got out of the hood…[At the museum,] there’s a feeling of, these people did it the right way, and others did it the wrong way, so they won’t get a statue. There’s no way for Great Blacks in Wax not to be political, because it’s about celebrating black people. But there’s a whole range of black people doing a wide range of things. You get the ‘I Have a Dream’ MLK, not the against-Vietnam MLK, the need-to-agitate, won’t-get-it-through-peace MLK. The 12 O’Clock Boys won’t be in there, but they represent Black Baltimore as much as Redd Foxx or Cab Calloway.”

Myers criticizes the museum’s inclusion of certain politicians, entrepreneurial millionaires, and especially Baltimore Republican Ben Carson.

“A certain respectability politics is difficult to gauge with reality. Ben Carson is respectability politics. We get told his story about pulling yourself out of the ghetto, about working hard enough, but he doesn’t represent the best ideals of African Americans in this country. It’s a capitalist perspective on what good is: making a lot of money, moving away from the city, turning your back on black people. Great Blacks in Wax can’t solve that, but that’s endemic to being a black American in a capitalist society. There’s the desire for black people to fit in and be perfect, when they’re still hated by the majority of people. I think the museum serves a great purpose. It’s good for black children who don’t get to see good things about themselves or see their history. There’s a pride aspect, because hey, we can be part of society. It’s good to see Jackie Robinson: he certainly hit those balls. But at the same time, the Booker T.’s say, ‘Go to college, get a good job, and eventually we’ll get to a good place’—when you’ve got Trayvon Martin living a pretty good life, but in the end it didn’t matter, because a dude steeped in white supremacy shot him and got away with it.”

How, then, to broach the complex subject of respectability politics with Martin, a historian and image-maker devoted to saving lives through education and inspiration, who must face white school principals, lawmakers, and funders in addition to the ongoing realities of systemic oppression? A woman who makes clinking noises as she walks—because she’s carrying an eighteenth-century iron collar and chain in her handbag—doesn’t get fazed by questions about her mission.

“Part of the fight is racism and how it continues to manifest itself. I never want to lose that,” she said. “We also fight against how we don’t value ourselves as people of African descent, and we kill each other. I also try to make the connections. We talk to the kids about voter suppression as it existed during the Jim Crow era, but also how it happens today. There’s a tragic connection between Jim Crow and the prison complex today. I talk about the slavery after slavery, the peonage system, where law enforcement was very much part of the plan to take black men in particular and put them back in virtual slavery—the convict lease system, where you were working as a slave then working as a convict. If you couldn’t show you weren’t a vagrant, or were charged with a crime that law enforcement knew you hadn’t committed, you were given a choice: to work on the plantation or go to jail. Or the sharecropping system, where you weren’t designed to get out from under. This now, with the prisons filled with black people, I see that as a throwback to an effort to create a second slavery.”

Regarding the ethos of respectability and empowerment, she says, “I never wanted to [let] the lynchers off the hook. We are fighting every day to stay alive. Everybody’s had to deal with the whole idea of violence. I have had to deal with it. We lose so many children each day, all over this country, and the violence has escalated to a frightening level. So for me, there are Trayvon Martins in all of this, Freddie Grays in all of this. The sacrifice, the role that our youth have played in making the world better by surviving slavery, fighting in the Underground Railroad, fighting for civil rights, and our young people who, every day, go out and sit on the front lines of battle—which is what it is to me—I’d like a memorial to those youth, something that speaks to all the children we have lost and continue to lose in this violent world that we live in.”

One of the oldest functions of the wax figure is memorial. Great Blacks in Wax commemorates Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and King, the Turners and Emmett Till, the millions of the Middle Passage—and Great Blacks much closer to home. When I first asked Martin why she and her husband had opened a wax museum, she laughed.

“This certainly wasn’t my design! I became an armchair historian, because my husband dragged me kicking and screaming into what I do now. Elmer was the activist, the person involved in civil rights, Black Power, and the Black Consciousness Movement. So was I, but I wasn’t the activist he was. But I definitely feel that Elmer gave me an opportunity to live my life in a way I find meaningful. The museum’s like walking around inside the head of Dr. Elmer Martin, a behind-the-scenes perspective of what he was thinking, what he was attempting to do.”

The National Great Blacks in Wax Museum memorializes Elmer’s vision, but it’s Joanne who must continue to address the crises and struggles of 2016. Of the “Blvd. of Broken Dreams,” she said, “It’s all Dr. Elmer Martin, that way of thinking about things; it’s truly his concept. But for me…through Elmer’s teaching, I have evolved, so that I can understand about listening to the visitors, to give a balance that the exhibit does not have, to lay out what the exhibits will be for the future.”

Doug Myers joked, “‘If they wanted to put up a wax statue of me, I wouldn’t say no. I’d tell everybody I dated, ‘I’m in Great Blacks in Wax. It doesn’t look much like me, but…’”

As Eric Cherry and I perused the display of prominent Baltimoreans, he said, “When I’ve got a group of elementary school kids, I take Ben Carson’s head off.”

He stepped over the barrier and, with a twist, lifted Carson’s head off his neck and placed it in my hands. “So they can feel it and take pictures with it. You want a picture?”

I held Ben Carson’s head at arm’s length. It felt hard, heavy, and solid—like a real head, I supposed. It was creepy. Intimate, funny, transgressive—and, after having seen the basement’s lynching souvenir collection, profoundly disturbing.

“That’s real human hair,” said Cherry. “Glass eyes. The ones like Osborne Payne or Harlow Fullwood, who had dentures, those are real dentures. When we’re downstairs, I give the kids Thurgood. His hair’s more curly.” He patted Carson affectionately. “You can touch his hair.”

I didn’t touch it. Eric took my picture: my smile is awkward. And thrilled. Nineteenth-century journalists also enjoyed behind-the-scenes visits to waxworks, cracking morbid jokes about the jumbled body parts but loving the Night at the Museum aspects, the privilege of holding the magician’s rabbit. Only little kids and the staff were allowed to handle Ben Carson’s head—and, now, me.

Cradling Carson’s head in my hands, afraid of dropping it and smashing the bright eyes and individually planted eyelashes, I thought about uncanny wax bodies. They show scars and burns. They glow, crease with wrinkles and smiles, and submit to dusting. They put on Union officers’ uniforms and dashikis; they get stalked by bears and Klansmen. They ride in a Pontiac to nursing homes and Lexington Market; they fly to NAACP conventions; they embody histories and the unfixed possibilities of life. Sparking loyalty, dissent, celebration, and grief, wax manifests the long endurance of sculpture and struggle, the vulnerability of art and bodies, and the love for them that these figures represent, as when Eric carefully replaced one figure’s hand—which had fallen off—back into its shackle.