At the worst, a house unkept cannot be so distressing as a life unlived.

—Rose Macaulay, 1925

Great Arch of Palmyra, c. 1860. © The Getty Museum, Ken and Jenny Jacobson Orientalist Photography Collection.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

The Greco-Roman city of Palmyra is perhaps the most extraordinary site archaeologists have ever uncovered, alongside Pompeii and the vast ruins of Ephesus. The city, however, is now infamous as a victim of terrorist barbarism. ISIS forces captured Palmyra, 150 miles from Damascus, in May 2015. They turned the city’s archaeological museum into a prison. Khalid al-Asaad, who worked for decades as Palmyra’s head of antiquities, was murdered. Its well-preserved theater was used to stage ostentatious executions. ISIS also destroyed many of the sites that made Palmyra unique. Of the shrine of Baalshamin, only four columns remain. The Temple of Bel was blown up, its prayer chamber destroyed. Famous second-century arches were destroyed. The list goes on. Why did ISIS need to destroy the temples? Because these were places where pagans before Islam came to adore mendacious idols? No, I don’t think so. It seems to me that the temples and artifacts of Palmyra were destroyed because they were venerated by citizens of the West. ISIS wanted to show that it doesn’t respect what Western culture admires.

In March 2016 Palmyra was recaptured from ISIS. This is a significant turn of events. And yet many of the ancient monuments and the irreplaceable art and artifacts that brought the ancient city to life have been marred or destroyed. Having studied Greco-Roman antiquity my entire professional life, I have often encountered Palmyra in my work. In light of recent events, I have taken up the task of sketching a new portrait of the city.

In the year 200 Palmyra was part of the vast Roman Empire at the height of its power, which extended from Andalusia to the Euphrates, from Morocco to Syria. When a traveler arrived in the merchant republic of Palmyra, a Greek or Italian trader on horseback, an Egyptian, a Jew, a magistrate sent by Rome, a Roman publican or soldier—in short, a citizen or subject of the empire—the newcomer immediately realized he had entered a new world. He heard an unknown language being spoken, a great language of the civilized world: Aramaic. (This stranger needed not worry about language, however; every rich person he encountered would have known Greek, the English of that time.) Local residents weren’t dressed like other inhabitants of the empire. Their clothing wasn’t draped but sewn like our modern clothing, and men wore wide trousers that looked a lot like those of the Persians. Noble Palmyrene horsemen, lords of import-export, wore a dagger around their waists, defying the prohibition against carrying weapons on one’s person that was imposed on citizens elsewhere in the empire. The women wore full-length tunics and cloaks that concealed only their hair; they wore an embroidered band around their heads, with a twisted turban on top. Others wore voluminous pantaloons. Their faces weren’t veiled, as was the custom in many regions of the Hellenic world. And so much jewelry! They may have been in the heart of the desert, but everything exuded wealth. There were statues everywhere, but they were made of bronze, not marble (there being no marble in Syria); in the great temple the columns had gilded bronze capitals.

To the south, and to the west as far as the eye could see, the desert was scattered with ostentatious monuments, funerary temples, hypogea, and multistory rectangular towers. These were the mausoleums where the great families—those who managed part of the trade between the Roman Empire and Persia, India, and China—buried their dead (whereas the Greco-Roman custom was cremation). To the north, outside the city, the visitor might have noticed strange beasts: camel caravans were stationed around large warehouses; one sensed that nomadism was not far off. When the visitor’s gaze turned back to the city and the palm grove, with its olive trees and vineyards, the massive sanctuary of the Temple of Bel, the patron god of this land, towered above the single-level houses, a sure sign, like the sight of a minaret for Westerners today, that one had entered a new civilization.

At first the shape of the temple resembled that of all temples in the empire. The newcomer would have been familiar with the shape of its Corinthian capitals and its Ionic capitals, which were a bit old-fashioned in 200. But when studied more closely, the building was disconcerting: it was the bizarre temple of a foreign god. The monumental entrance was not at the front, as would have been logical; it was surprisingly placed on one of the long sides. The top of the building was heavily crenellated, something found only in the Orient. And it had windows; a temple with windows, just like a house, had never been seen before. Most surprising was that instead of having a roof with two sloping sides, as did all other temples, it was covered with a terrace. Again, just like a private dwelling. In this region people went up to the roof terrace to eat, feast, or pray to the divinity, at the risk of falling off, as did a young man, according to the Acts of the Apostles.

Without a doubt, our visitor would have seen a great deal to shake his sense of normalcy. In the Roman Empire, or rather the Greco-Roman Empire, everything was uniform: the architecture, houses, written language, clothing, values, authors, and religion, from Scotland to the Rhine, the Danube, the Euphrates, and the Sahara, at least among the elite. Palmyra was a city that felt, by contrast, dangerously close to Persian civilization, the great enemy of Rome, and to even more remote places.

Today, to get to Palmyra it takes four hours by plane from Paris to Damascus; then you have to travel on a paved road that follows the traces of an ancient route. Upon arriving, visitors discover not the “lost jewels of ancient Palmyra” about which Baudelaire wrote (almost no jewels have been found) but a modern town with hotels and restaurants.

Transitory Places I. Cinema Metrokino, Vienna, Austria, by Laura Ribero, 2013. Chromogenic print, nine-photo series. © Laura Ribero, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Hubert Winter, Vienna.

What is most striking for the contemporary visitor is what already struck the ancient traveler: a huge sanctuary, today blasted apart, and a long colonnade, those “streets of Palmyra, those forests of columns in the desert plains” Hölderlin dreamed of as a child. Trade with the outside world had transfigured an Aramaean oasis, just as it would turn a few muddy islands on the Adriatic into Venice. The colonnade represented avant-garde urbanism and everyday life in Palmyra, and the Temple of Bel was the San Marco of this desert port.

The temple was not a monumental reliquary or a shrine, as temples were in Greece and Rome; it was the home where Bel lived and where his statue sat on a throne as the saint of all saints. The building rose up in the middle of a rectangular enclosure two hundred feet on each side, looking inward at the four sides. This enclosure was quadrilateral, with porticoes supported by columns; from the exterior, one saw almost windowless walls that protected the temple (just as the admirable mosques of Istanbul remain separate from the city in their large courtyards).

The porticoes were not just ornamental or used as shelters against the sun; they offered pilgrims an indispensable campground. Here merchants sold religious objects that could be offered to the god and also, I imagine, poultry, which those of lesser means could offer up as sacrifices. On the back wall, devout pilgrims engraved in the plaster the written proof of their visit to the temple, or their thanks to the god who had answered their prayers.

The temple was consecrated in 32; the enclosure and its porticoes must have been constructed only gradually, over decades; many other pagan or Christian sanctuaries were completed over centuries. The temple itself is not that big, a surprise in that Syria was quite fond of all things large—it was one of the wealthiest provinces of the empire, along with Tunisia and eastern Turkey.

As for the long colonnade (whose path was not paved in stone), today it crosses the entire site, from the Temple of Bel to the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian. This double line of columns that rise up to the heavens and no longer support anything was completed over two centuries. The colonnade was not a normal road; one mustn’t imagine caravans traveling along it—they certainly did not enter the city. Along part of the great avenue was the souk of Palmyra, “the portico under which everything was sold,” the place where people strolled. The souk had regular geometrical dimensions, which conformed to the rational design of a place where one went rather than a passageway to somewhere else.

In every ancient city, large or small, the circulation of private conveyances and horseback riders was forbidden. Only wagons carrying goods were allowed to enter the city, while individuals left their mounts and their carriages outside the city walls. However, the streets were often encumbered by herds of livestock that passed through to be slaughtered for the consumption of city dwellers. And every morning, many of those city dwellers left the city and, in the evening, hurried to return before the city gates were shut; they had spent the day working in the fields.

Palmyra was a true city-state, following the Greco-Roman concept. This was a new idea in Syria, which knew only royal, religious, or funerary edifices: surrounding walls and gates, temples, palaces, and tombs. Large-scale urbanism became widespread only in the Roman period. We should mention how popular colonnades really were. It was probably Antioch, the capital of Syria, that was the first city to have these avenues with paved streets lined with hundreds of columns.

As in Rome and elsewhere, in Palmyra the columns of the avenue supported porticoes, and under those overhangs were doors that opened onto shops. From what we have learned, shopkeepers and tenants paid rent to the city or to a temple treasury, depending on who owned the building. If the shop was that of a cobbler who lived off his daily earnings, it also served as his lodgings for the night, I imagine, as in Pompeii, Herculaneum, and, only fifty years ago, in old Naples. In addition to a marketplace, a city worthy of the name had to have a public space, a forum, an agora. Palmyra had one, and it appears to have followed a guiding architectural principle: its columns rise up perfectly straight, it boasts four porticoes, and it is decorated with two hundred official statues.

But where was the city itself? Where did the inhabitants live? Excavations to the north of Palmyra have revealed streets and homes that were more or less lined up between the great colonnade and the current town. The remains of a few houses can still be seen. Some appear to have been homes of wealthy proprietors, similar to the type of private home common throughout the empire: a single-level dwelling spreading out over hundreds of square meters, opening up onto a central courtyard surrounded by porticoes; mosaics no doubt decorated the ground and the walls.

Other houses sheltered a more modest bourgeoisie; from the exterior their layout is similar, but a few details indicate that life was lived differently in them. Two identical doors opened onto two well-separated areas of the home, one where guests were admitted and one where women lived, which was off-limits to anyone else. These homes had only rare openings onto the exterior. The streets thus resembled those of an old Muslim or Greco-Roman city such as Pompeii, where, apart from the commercial street, one passed between two practically windowless walls.

The architectural layout of this northern area appears to have had a geometrical design, but one that was carried out haphazardly, with inexact perpendicular lines and an approximate parallelism; one imagines that preexisting constructions—temples and private dwellings—were later more or less connected by a network of streets. Clearly, this area was first occupied by scattered structures. For more than five hundred years, Mediterranean cities had been strictly geometrical; at least in the fourth century, this was the case in the Persian quarter in Beirut. This orthogonal layout was that of the cities that had been founded by Greece and of those that Rome implanted everywhere, from Bavay to Carpentras in France to as far as Timgad on the edge of the Sahara in Algeria. An ancient city such as Athens seduced tourists with its mazelike streets. Palmyra wanted to be modern, and at that time, Greek civilization was de rigueur. Palmyra was foreign to that civilization by dint of its past, its Aramaic language, its society, its caravan activity, its religion, and its many different customs. In Syria, the more important a building, the more Hellenized it was. Only Greek architecture was conceivable.

The population of the entire Palmyrene city must have been only in the tens of thousands. Other Palmyrenes lived scattered throughout the rural territory that belonged to the city. Let’s remember that at that time the entire Italian peninsula had only six million inhabitants. At a time when a society could survive only if three-quarters of its members worked the land to feed the population, the largest urban areas, such as wealthy Venice in the sixteenth century, rarely reached 150,000 inhabitants. A huge metropolis such as ancient Rome (500,000 inhabitants, or double that) was the exception.

Life must have been expensive in Palmyra because its surrounding territory was not sufficient to provide it with everything it needed unlike most ancient cities, which couldn’t have survived otherwise. It drew salt from the lagoons of the desert and resold it, but it had to import wheat, wine, and oil—the trinity of Mediterranean lands—which it did not produce in sufficient quantities. The land was better suited to raising goats and sheep for the consumption of the city dwellers, camels for the caravans, and horses for the armed guards who escorted them. Palmyra also imported garum, similar to Vietnamese nuoc mam: fermented fish sauce, a common condiment in ancient Middle Eastern and Asian cuisine.

Like every ancient city, Palmyra did have a vast territory (to the west, its borders were forty miles away). The city and the palm grove were not right in the middle of the desert but close to its border, and so the Palmyrene territory was essentially situated in the critical zone with seven inches of annual rainwater that made farming and livestock husbandry possible. In the areas closest to the city, the groundwater was collected through underground canalization, accessible by wells that were scattered over the area. To the east was the desert, but to the north archaeologists have discovered villages of livestock farmers whose unfired brick houses were topped with terraces, and villages with entire cistern systems. Palmyra’s other large rural zone was thirty miles to the south, irrigated by a large Roman-era dam.

Every house: temple, empire, school.

—Joseph Joubert, 1800The city proper was inhabited mainly by landowners who spent what they earned off their land there, by the shopkeepers who provided goods and services, and by their large number of domestic servants. This domestic help was the urban poor. They filled the homes of the wealthy. The truly poor—poverty-stricken peasants—did not live in the city.

The oasis of Palmyra was also a commercial center where peasants from the countryside would come to sell their wares before going to the souk for their own provisions. The private homes of the regional landowners occupied the rest of the space. But here is what made Palmyra unique: the beautiful homes there were inhabited not by the landowners but by the agents of the caravan business. Palmyrenes, wrote an ancient historian, “as they are a trading people, they bring Indian or Arabian products from Persia and market them in Roman territory.”

From Arabia and the Orient, Rome indeed imported goods that were not very heavy but which were in demand: not the heavy cargo of grain or minerals but bundles of incense for all the sanctuaries of the empire, myrrh, pepper, ivory, pearls, and Indian or Chinese fabrics (bits of Chinese cotton and silk have been found in the tombs of Palmyra, where the bodies were often mummified). Roman women wore robes of silk more revealing than if their wearers were naked; moralists and poets railed against them. But even men, above all senators, ultimately adopted silk clothing.

This sumptuous commerce was criticized by moralists and by those who criticized Rome for importing goods instead of focusing on exporting; however, what was imported did not amount to much on an imperial scale (it may have represented 0.5 percent of the GNP). But it was enough to make a handful of importers rich, who thereby earned a revenue equal to what several hundreds of thousands of inhabitants might earn. Their profit came from the huge gap between the buying price and the selling price; our sources—a Latin naturalist and a Chinese informant—speak of goods that were sold for ten or even a hundred times more than their purchase price. For various reasons, we cannot provide the current monetary value of the ancient prices, but here is something that is very telling: just under a pound of raw silk from China sold for the price of tens of thousands of eggs or of six thousand haircuts, or for sixteen months of a farmworker’s salary, not counting what he paid for food. The average cost of living and salaries in the empire were those of current developing nations, with a gap like the one we currently know of between mass poverty and enormous fortunes. Let’s hazard a comparison with the salary of the average Palmyrene: he or she would have earned forty dollars per month, on average, or half that, or double that, but not ten times that.

At the time when Palmyra was at the height of its glory, a Chinese informant was sent westward and arrived in Syria. “The inhabitants are honest in business, and there are no double prices,” he reported, adding that commercial profit was tenfold. But, he says, the Persians “want to continue to sell their Chinese silk, and this is why these inhabitants are cut off from all direct communication with the Chinese.” And so Palmyra sought its treasures from India and Arabia, and those treasures got there by two routes: by boat on the Persian Gulf or via the Silk Road.

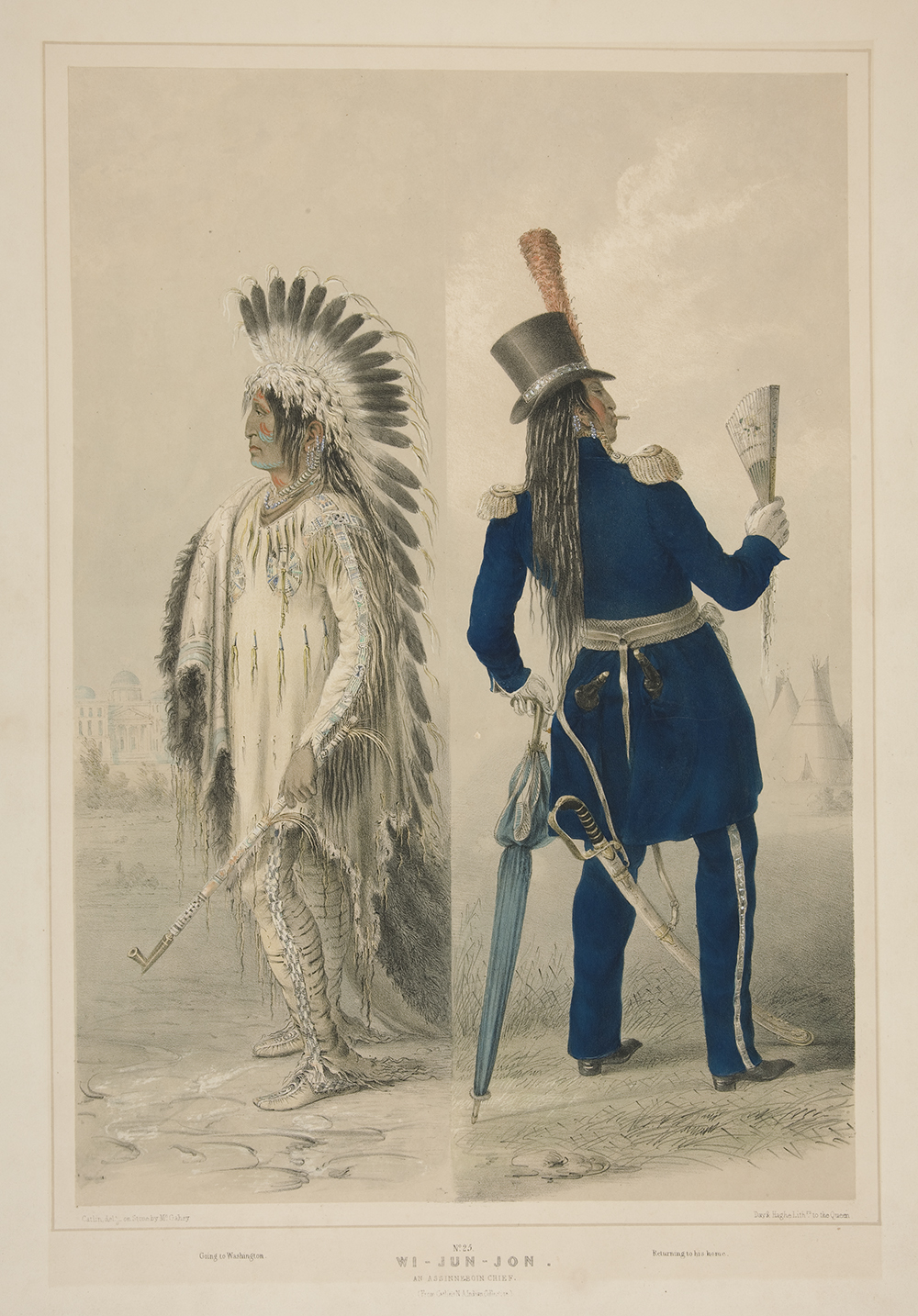

Wi-Jun-Jon, an Assinneboin Chief, Going to Washington; Returning to His Home, by George Catlin, nineteenth century. © Yale University Art Gallery.

The land route led from the Euphrates to Punjab and the Huang He (Yellow River). The sea route left from the base of the Persian Gulf and, with the help of the monsoon, led to a trading center at the mouth of the Indus, near Karachi; then it traveled south along the Indian peninsula to Ceylon (Sri Lanka), then back up to the outskirts of Pondicherry, where spices and silk could be traded for wine, Syrian glass, and beautiful red-glazed pottery made in Arezzo, Tuscany, a common, everyday type of vessel that became expensive only because of how far it had traveled. Once back from their expedition, which might have lasted between one and several years, sailors and traders told of what they had learned on their travels. This is how Rome came to know of the existence of the Great Wall.

Palmyra’s role in all this was to help get the merchandise over the eight hundred miles that separated the cities and ports of Syria from the Persian Gulf and the sea route, by crossing the Syrian desert to the welcoming banks of the Euphrates and the fertile Persian territory; this was the annual adventure of the large caravans. The bartering and the palavers with tribal chiefs and the bribing of the Roman and Persian customs officers were done in Greek and Aramaic, the international languages of business.

We can see what made Palmyra so prosperous: it is on the shortest path between the Mediterranean and the Euphrates; this path was only a road in the rocky desert. But Palmyrenes were technicians of the desert; those camel drivers knew how to cross from one water source to the next, a difficult journey in summer, and one that was threatened by attacks from nomads.

The Palmyrenes were able to build a commercial empire from what might have been merely transport services. They bought and then resold what they were transporting; traders were part of the caravans. What is more, some of them armed the ships on the Red Sea, thereby competing with their Egyptian rivals. Palmyra was not just a caravan city; it was a merchant republic.

They represented a type of entrepreneur that was quite different from the one Max Weber discovered at the origins of modern capitalism: that is, the Protestant businessman. The Palmyrene capitalist was a horseman, a warrior, a sheik: the de facto chief of the more or less sedentary tribes of the Palmyrene territory and the desert. It was thanks to him that Palmyra was able to bring its commercial potential to fruition; his authority and audacity made use of competent caravan leaders.

It is unlikely an exaggeration to say that this Aramaean city, with its networks of clans, of clientele and lineages, was unlike any other Syrian city. It resembled less a city of the empire than it did other merchant cities like Mecca or Medina in the time of Muhammad (who in his youth took part in caravans). Like those Arabian cities, Palmyra was not structured around a civic body but around a group of tribes, and it was dominated by a few families of merchant princes. The magnates of Palmyra, proud of an authority that gave them license to pursue bold undertakings, knew the wider world and profited from it.

Translated from the French by Teresa Lavender Fagan.

This essay is adapted from Palmyra: An Irreplaceable Treasure, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2017 by the University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.