Battle scene, thirteenth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Jerome A. Straka Gift, Fletcher Fund and Margaret Mushekian Gift, 1975.

Sultan Saladin is a man of myriad guises in the memory and the imagination of the West. The sheer diversity on display is astonishing: time traveler, master of disguise, a just ruler, and a pillar of nobility, or an unscrupulous chancer, a rapist, and tormenter of the Christian faith are just a few of the vices or virtues attributed to the sultan. The starting point for what ultimately became a positive characterization was an unlikely one. The capture of Christendom’s most holy sanctuary by “the son of Satan” inflicted immeasurable spiritual harm on the West, yet over time, a blend of fact and fiction came to dilute and then to transform Saladin’s image.

In every instance, it is the particular context and audience that steer such perceptions, but because the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem was such a profound blow to the people of western Europe—to some, a sign of the impending apocalypse—any change in attitude toward the author of this calamity warrants our attention. For the transformation to be, at times, so complete and certainly so durable, running down even to the present day, is curious. Given this longevity, the framework is vast, drawing in the centuries-long history of crusading and encompassing the evolving relationship between Christians and Muslims. From beneath these great themes Saladin has emerged to hold an overwhelmingly positive image in the West. It is, I would venture, impossible to think of another figure from history who dealt such a deep wound to a people and a faith, and yet became so admired. The Saladin whom we encounter is, in many senses, a literary construct, yet one with tangible historical foundations, upon which have accumulated layer upon layer of authorial agenda and aspiration.

The Saladin of literature had a prolific romantic career in Europe. He frequently became a master of disguise, and texts in Middle Dutch, Old French, and Occitan, as well as works produced in Italy and Spain, bear testimony to his character’s wide literary appeal. Such skills enabled him to come to the West to learn more about, variously, the Christian faith and the strength of western Europe (a sort of pre-Crusade recce), and to meet Western ladies.

Occasionally he was rebuffed, but there was a long list of other conquests, including the chronological challenge of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Setting aside the fact that Saladin was aged only eleven when she was in the Near East, the Minstrel of Rheims, author of a collection of entertaining anecdotes and stories from the Crusades, tells us that Eleanor, fed up with the rather dull Louis VII, learned of the prowess, wisdom, and generosity of Saladin. She offered to renounce her faith and to be his lady. The sultan sent a ship to collect her, but a servant warned Louis and the escape bid was foiled. When asked by the king to explain herself, she answered that Louis was not worth “a rotten apple. And I have heard so much good said about Saladin that I love him more than you.” The couple returned home and the king repudiated her. Multiple variations on this tale emerged in the popular imagination, all glossing the image of Eleanor as a flighty adventuress and of Saladin as a glamorous and charming infidel.

With his knightly worth, his romantic allure, and an ability to visit the Latin West incognito, it was only one small step further to bring Saladin into the Christian fold. Crusade epics frequently included tales of an admirable opponent who converted to Christianity, which implies this was a reasonably familiar path, although not for a man of such high profile. Another literary tradition that first dates from the eleventh century is that of a parable that weighs up the claims of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, and by the late thirteenth century Saladin began to feature in these stories. A further variant was the sultan, on his deathbed, ordering a debate between the caliph of Baghdad, the wisest of the Jews, and the patriarch of Jerusalem.

It was the populist Minstrel of Rheims who finally ushered Saladin over the religious boundary line, albeit not entirely without a whiff of ambiguity. Given the understandable presence of the sultan’s family at his deathbed, he had to perform a covert auto-baptism, asking for a bowl of water, making a secret sign of the cross, and then pouring the water over his head and muttering three words in French that no one managed to catch. Needless to say, other authors repeated the story, or something akin, with one widely circulated version conflating the religious debate with the auto-baptism. Regardless of the utter implausibility of these various scenarios, the basic point remains that Saladin possessed many of the virtues that the West admired. These “compensating fictions” enabled writers to embrace him in their literary and historical worlds, deflecting from the harsh reality of his achievements and forming a more attractive and palatable alternative.

Within the Divine Comedy, Dante’s landmark narrative poem completed in 1320, are the three divisions of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. In the first circle of Hell stands a fine castle reserved for noble pagans and in the main inhabited by classical poets, philosophers, and heroes, unable to enter heaven but nonetheless entirely worthy of comfort and recognition. Only three Muslims are allowed to join them. Two of them, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes), were philosophers; the third, “by himself, apart,” was Saladin, the only man to have tangibly inflicted damage upon Christendom, yet by virtue of his character present in this privileged company. Dante’s poetry also recalled Saladin’s munificence.

A few decades later Giovanni Boccaccio wrote his influential Decameron, a collection of stories within which Saladin appeared prominently on two occasions, displaying his famous generosity, acuity, and good graces. Boccaccio later produced his On the Fates of Famous Men, in which Saladin featured as one of the fifty-six individuals selected. In Castile, the nobleman Don Juan Manuel wrote his Luanor in the 1340s and deployed Saladin as an interlocutor on contemporary politics and moral life. In his search of the most important human virtue, chivalry, he traveled into France and to the papacy, his Muslim origins far removed from the southern Iberian and North African Moors encountered by the author at the time. Soon after this, the Italian poet and scholar Petrarch composed The Triumph of Fame, in which he wrote that the foremost figure amongst the furthest tribes was “mighty Saladin, his country’s boast, the scourge and terror of the baptized host.”

As was evident to all, Saladin was a man of huge generosity. At his death, contemporary Muslim sources reported that he was practically penniless, and from this vein probably emerged another enormously pervasive anecdote. As he lay dying, the sultan supposedly commanded one of his retainers to walk through his lands bearing a shroud or shirt suspended on a spear and to proclaim that this was the only possession that he would take with him when he died. It was a story that quickly made its way across to the Franks. Jacques of Vitry, a leading churchman of the early thirteenth century and a man usually highly critical of the sultan, employed it in his sermon c. 1213–21 on a good death; worldly possessions should be shunned, and Saladin’s humility was cited as a particularly fine exemplar. The Dominican Stephen of Bourbon took up the tale, as did many more preachers and historians; likewise chroniclers repeated it across France and in Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands.

While it is easy enough to cite what can be familiar instances of Saladin’s presence in famous works, it is worth tracing the wider diffusion of some of these images. From the latter decades of the fifteenth century the emergence of printing presses slowly began to bridge the gap between elite and popular cultures in western Europe. Rising literacy was both a trigger and a response to this, meaning there was a growing market for the printed word, from its most elevated form to the most trivial. Between 1660 and 1800 it is argued that over 300,000 book and pamphlet titles appeared in England alone, producing sales of perhaps 200 million copies. The issue of the reception of texts involving Saladin is difficult to ascertain; were they regarded as fact, or fiction, or both?

Matthieu Coignet was a French lawyer and royal adviser whose advice book Instruction aux princes pour garder la foi promise of 1583 was swiftly translated into English; here the tale of the shroud was related in the context of the humility of kings. In 1653 William Ramsey, a physician and astrologer, wrote An Introduction to the Knowledge of the Stars, and in a lengthy opening section he reflected on God’s power and that when humans died, they took nothing of material value with them, thus: “you have heard what the great conqueror of the East, Saladin, carried to his grave of all he had gained: but a black shirt.” Here the hero of Islam is slotted comfortably alongside, and into, Christian theology. Finally, in 1781, the Scottish Enlightenment figure Henry Home, Lord Kames, wrote his Loose Hints upon Education, Chiefly Concerning the Culture of the Heart and was pleased to praise the actions of a man for whom “there was no vanity here, but an angelic moderation preserved amid illustrious victories.” The didactic potential of this tale was plainly too strong to resist.

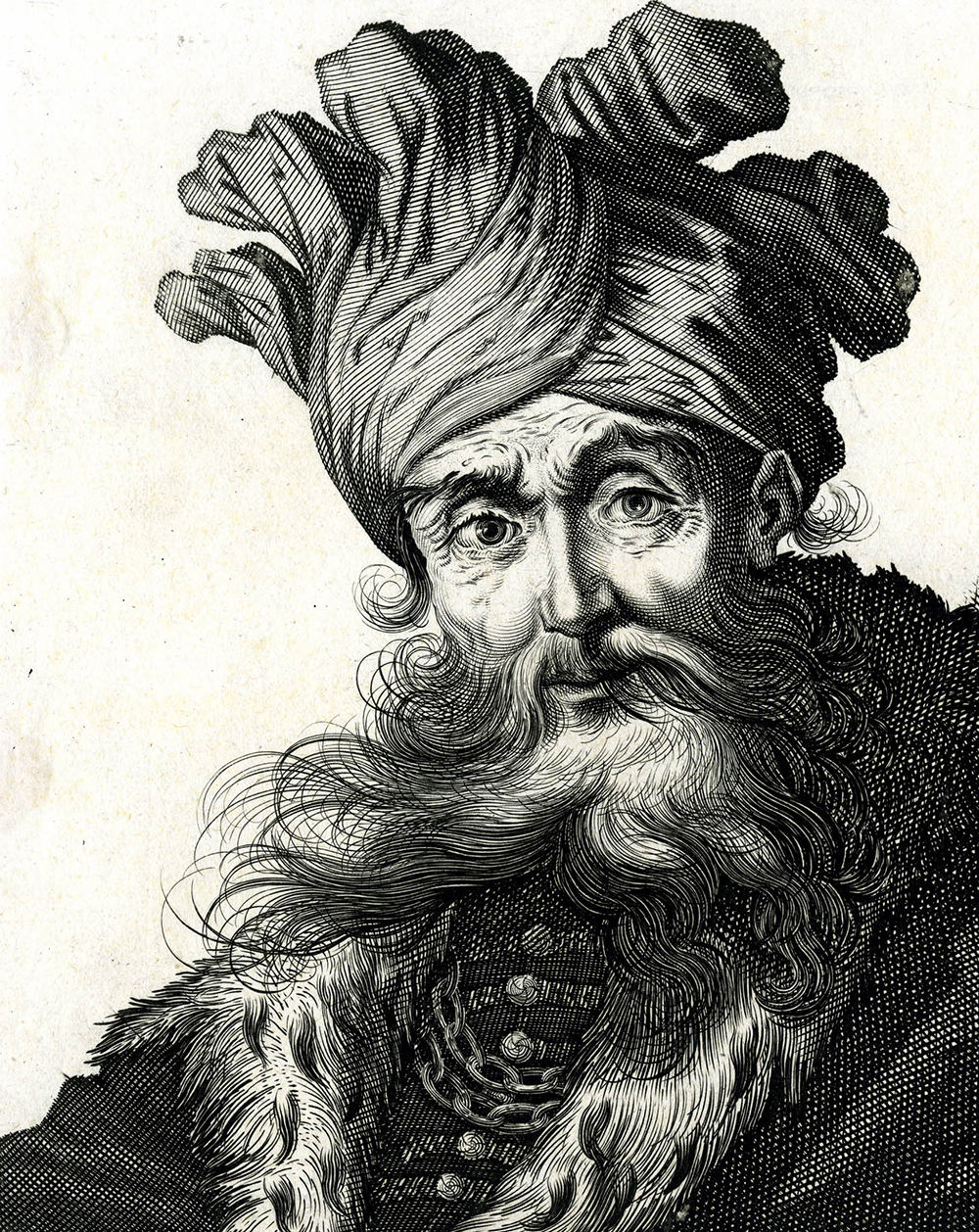

Not all of these stories were in as weighty a context, and accounts of Saladin’s amorous adventures were likewise circulated and repeated in multiple forms, just one example being the translation of The Royal Mistresses of France, Secret History of the Amours of All the French Kings in 1695. The sultan’s romantic liaison with Eleanor of Aquitaine is enthusiastically reported with her attraction to the young warrior easily explained: “’Twas said of him he was a person well shaped, nimble in all manner of exercises, valiant, generous, liberal, courtly, and in a word, that he was endowed with French manners.” More serious historical inquiry concerning the Crusades in this period tended to divide on confessional lines, although by the seventeenth century more nationalistic readings of (often) French scholars were set against a background of ongoing tensions with the Ottomans; within this Saladin could emerge creditably as the dignified conqueror of Jerusalem. In 1639 Thomas Fuller produced his successful Historie of the Holy Warre. The frontispiece features an image of the sultan framed by the phrase “This black shirt is all Saladin, conqueror of the East, hath to his grave,” perpetuating this popular belief. In the text itself, Fuller suggested that historians often described princes as how they should be rather than how they were, “but finding this Saladin so generally commended of all writers, we have no cause to distrust his character.”

By the time of the Enlightenment the Crusades were subject to withering disdain. Voltaire viewed the campaigns as an irrational and pointless exercise. Saladin, however, emerged in a more positive light as a tolerant, civilized character. In the 1750s Voltaire chose to blend some of the history with a couple of the more legendary aspects of the sultan’s reputation, including his single combat with Richard I and deathbed auto-baptism. Soon after this, François-Louis-Claude Marin published the first Western-language Histoire du Saladin (1758), a serious scholarly attempt to evaluate the sultan. In the context of Enlightenment criticism of “fanatical” religions, and a view of Muslim rulers as cruel and ruthless despots, Saladin emerges remarkably well, governing through moderation, generosity, and clemency. The author was unconvinced by the stories of Saladin’s various romantic adventures in the West, although he indicated his belief that the sultan had been dubbed a knight. “Finally,” Marin concluded, “an astonished Europe admired in a Muslim virtues unknown to the Christians of that century.”

The most influential picture of Saladin emerged from the pen of Sir Walter Scott in The Talisman (1825). Scott “turned history into a pageant,” and his practice of “inserting sympathetic, enterprising characters into the company of real kings and queens” was extremely popular. The Talisman itself was immensely successful and soon translated into numerous European languages, including German, Norwegian, Italian, Russian, and French, and it sold well in the United States, too. This was also a time in which the technology of printing and paper production stepped forward again, as did the ease of distribution of the printed word. Governments began to introduce legislation that encouraged formal education, further increasing literacy levels while lending and circulating libraries had already emerged to create greater accessibility to the printed word. The Talisman went into multiple editions, inspiring dozens of works of art and theater, again across Europe and also prompting further fictional accounts. Saladin stands as an obvious exception to the largely negative contemporary image of the Orient, and he reverses stereotypes. As Scott wrote: Richard “showed all the cruelty and violence of an Eastern sultan. Saladin, on the other hand, displayed the deep policy and prudence of a European sovereign.”

Adapted from The Life and Legend of the Sultan Saladin, by Jonathan Phillips, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2019 Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.