Zeus: Come, Ganymede—for we have arrived at the proper place—kiss me now, that you may know that I have no longer crooked beak, nor sharp talons, nor wings such as I appeared to you, under the semblance of a bird.

Ganymede: Were you not an eagle but just now, fellow, and did you not pounce down and carry me off from the midst of my flock? How then have those feathers fallen off from you entirely, and you have now come out in quite a different character?

Zeus: But, my dear boy, you see neither a man nor an eagle, but it is I here, the king of all the gods, who have metamorphosed myself at the right moment.

Ganymede: How? What, are you the great Pan? Then how haven’t you panpipes, or horns, and hairy legs?

Zeus: Why, you take him to be the only divinity?

Ganymede: Yes, and we sacrifice to him an uncastrated he-goat, bringing him to the grotto where the god stands. But as for you, you seem to me to be some kidnapping slave-dealer or other.

Zeus: Tell me, have you never heard the name of Zeus, nor seen on Gargarus an altar to the Rain Sender, and Thunderer, and Lightener?

Ganymede: Do you say, fine sir, that you are the same who but lately poured down on us that quantity of hail, who is said to live up above, who makes such a din, to whom my father sacrificed a ram? Then, how have I wronged you that you have carried me off, O king of the gods? Already, I doubt, will the wolves be falling upon my unprotected sheep and tearing them to pieces.

Zeus: What! Have you, who have been made immortal, and who are to live with us here, still a regard for your sheep?

Ganymede: How do you say? Then will you not this very day take me down home to Ida?

Zeus: By no means. In that case, I should have changed from a god into an eagle to no purpose.

Ganymede: My father, then, will certainly be looking for me, and be angry at not finding me, and I shall be whipped by and by for having left my flock.

Zeus: Why, where will he see you?

Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, by Mary Cassatt, 1878. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

Ganymede: Don’t keep me, please, for I am already longing to see him. And if you will take me back, I promise you another ram shall be sacrificed by him as my ransom. We have the three-year-old one—that fine one, who leads the flock to pasture.

Zeus: [aside] How simple and innocent is the child—a child yet all over, truly! But, my dear Ganymede, bid farewell to all those things and forget them, your flock, and Ida; and you from this place—for you are now enrolled among the celestials—will do many services both to your father and to your country. And instead of cheese and milk, you will eat ambrosia and drink nectar—this latter, indeed, you shall yourself pour out and offer to the rest of us. But, what is more than all, you will no longer be mortal, but shall become immortal, and I will make your star shine very bright, and, in a word, you shall be happy.

Ganymede: And if I want to play, who will play with me? On Ida there were many of us playmates of the same age.

Zeus: Here, too, you have a playmate—Eros there, and any number of knucklebones. Only cheer up and be bright, and don’t hanker after any of the things down below there.

Ganymede: In what way can I be of use to you? Must I look after flocks and herds here, too?

Zeus: No, but you shall pour wine into the goblet, and you shall be placed in charge of the nectar, and shall have the care of the banqueting hall.

Ganymede: That’s no hard matter, for I know how to pour in milk and to pass about the milk bowl.

Zeus: [aside] There again he is thinking of his milk, and fancies that he will have to wait upon mortals—but this is heaven here, and we drink, as I told you, the celestial nectar.

Ganymede: Is it sweeter than milk, Zeus?

Zeus: You shall know for yourself shortly, and when you have once tasted it, you will not again have any longing for your milk.

Ganymede: But where shall I sleep at night? With my playfellow, Eros?

Zeus: No. I carried you off on this account—that we might sleep together.

Ganymede: Why, could you not sleep alone; but is it pleasanter to you to sleep with me?

Zeus: Yes, with such a one as you, Ganymede, so handsome as you are.

Ganymede: Why, how will handsome looks give you pleasure, in respect to sleep?

Zeus: They have a certain sweet charm, and bring it on more softly.

Ganymede: Yet my father used to be annoyed with me when I slept in the same bed with him, and used to tell me in the morning how I had taken away his sleep by my restlessness and kicking and talking in my sleep, for which reason he would generally send me to bed with my mother. If it was on that account, as you say, that you carried me off, it is high time for you to put me down on the earth again; or you will be annoyed by being kept awake, for I shall disturb you by my continual tossing about.

Zeus: In doing that very thing you will most please me—since I shall keep awake with you in frequent kisses and embraces.

Ganymede: You would have to see to that yourself. As for me, while you are kissing me, I shall lull myself to sleep.

Zeus: We shall know what is to be done then. But now take him away, Hermes, and when he has quaffed immortality, bring him to us to be our cupbearer, having first of all instructed him how he is to hand his cup.

From Dialogs of the Gods. In other tellings of the myth, Zeus gives to Ganymede’s father a pair of immortal horses in exchange for his beautiful son. The abduction became a subject for Greek vase paintings, and the word catamite, meaning a boy kept for homosexual practices, derives from Ganymede’s name in Latin. William Shakespeare drew inspiration from one of Lucian’s plays for Timon of Athens, and Ben Jonson took the idea that Helen of Troy “launched a thousand ships” from Lucian’s Dialogs of the Dead.

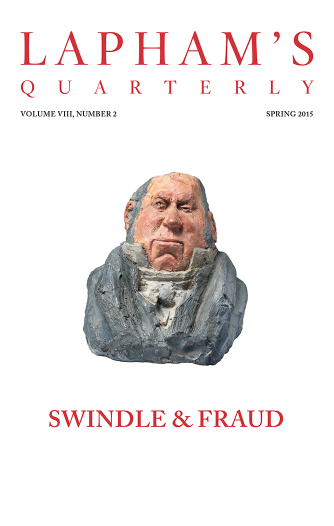

Back to Issue