Lake Condah, Victoria, c. 1880. National Library of Australia.

Rain fell heavily on the morning of July 9, 1841, when George Augustus Robinson heard a single gunshot. Two of Robinson’s companions had fired at a kangaroo, so the fifty-three-year-old chief protector of Aborigines mounted his horse and set off toward Budj Bim, a dormant volcano in western Victoria. Robinson, riding in haste, was concerned that the gunfire may have startled the Indigenous Australians he was there to meet.

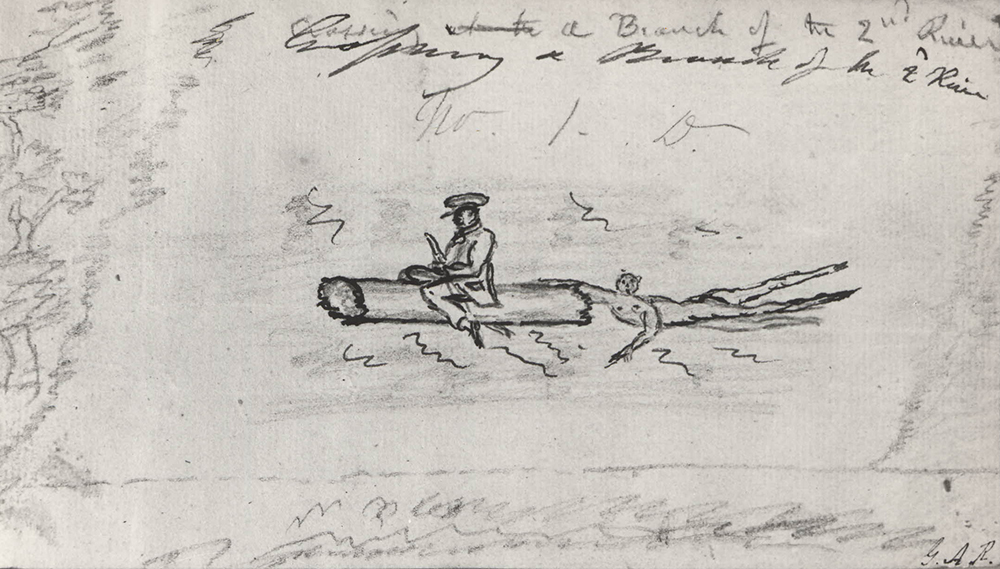

After riding a mile through the verdant bush, Robinson came upon a marshland by a lake—later named Lake Condah—and there he saw something wholly unexpected: “an immense piece of ground trenched and banked,” as Robinson recalled in his journals, “resembling the work of civilized man but which on inspection I found to be the work of the Aboriginal natives, and constructed for the purpose of catching eels.” These trenches were hundreds of yards in length. “I measured at one place in one continuous triple line for the distance of five hundred yards.”

The “civilized” design of these canals countered everything Robinson thought he knew about the Aboriginal culture he had been tasked with protecting. For the forty years of Australia’s colonization, white settlers considered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to be nomadic hunter-gatherers, a view enabling Europeans’ beliefs in their cultural superiority and in their right to claim the land. Here Robinson observed evidence to the contrary: signs of eel farming, engineering, food preservation, settlement, possibly even trade—all harbingers of civilization. Yet none of this would be given due credit until over a century later.

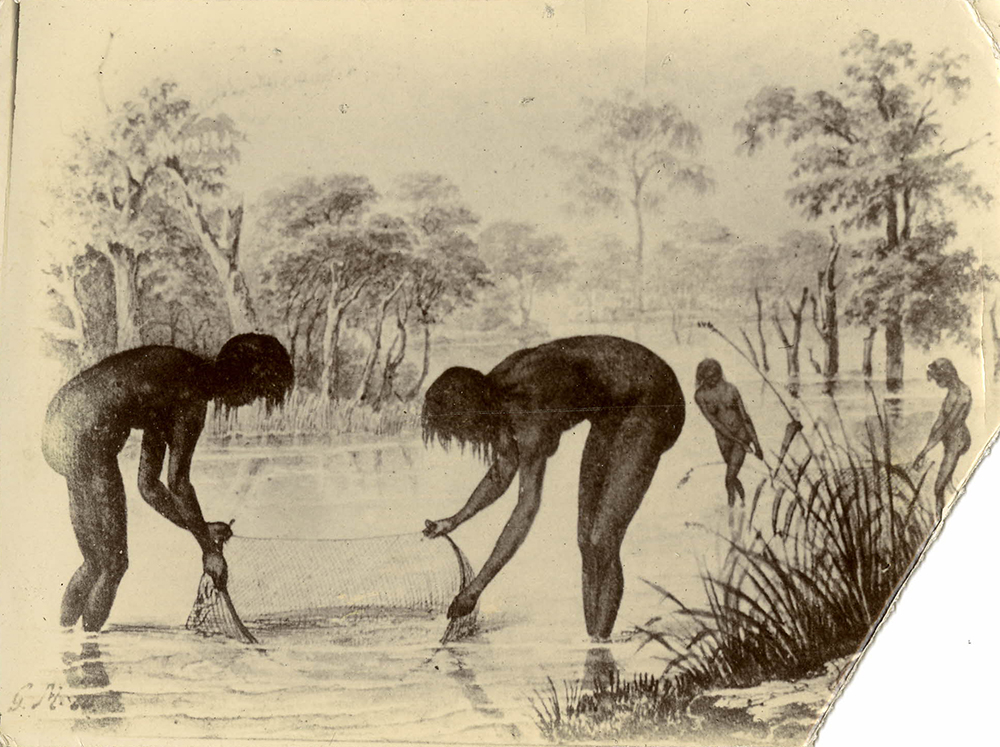

The machinations of the fisheries were intricate: along the winding canals—chiseled with sticks and smoothed by hand into trenches—were low stone walls built from the area’s volcanic basalt rock. These walls had small holes through which shortfin eels would swim and be caught in woven traps. The canals were strategically located to benefit from the lake’s seasonal flooding, at which time the eels would be drained from the lake along with the floodwaters. “It is hardly possible for a single fish to escape,” Robinson wrote.

These triple water courses led to other ramified and extensive trenches of a most torturous form. An area of at least fifteen acres was thus turned over. The whole reminded me of the extensive circumvallations of, in miniature, Chatham Lines, at which works, at an earlier period of my life, I had been engaged with the veteran engineer Colonel De Arcy for seven years.

Alongside these fisheries, Robinson saw something even more remarkable: “Around these entrenchments was a number of large ovens or mounds for baking, there were at least a dozen in the immediate neighborhood.” These earth oven mounds, where the eels would be cooked, were immense. “One I measured was thirty-one yards long, two yards high, and nineteen yards broad,” he wrote.

The most recent dating of the fisheries suggests that the oldest parts of the canals are about 6,600 years old, constructed around the time that Mesopotamians were inventing the wheel. Robinson’s 1841 journal stands as one of the first written records of the site, but this significant discovery did little to dissuade white Australians from their belief that Aboriginal people were incapable of sophisticated engineering.

In 1883 Alexander Ingrim, a Scotsman who had immigrated to Australia when he was a child, found himself working as a surveyor on the government’s drainage scheme at Lake Condah (a plan to improve water flow out of Lake Condah and into Darlot Creek) when he first noticed what he called the “Aboriginal fishery.” Anthropologically curious, Ingrim set out to map the elaborate engineering of the canals in 1893 with the help of fellow amateur historian Reyell Eveleigh Johns. (Johns’ interest in Indigenous culture was not wholly respectful—he was also a notorious robber of Aboriginal graves.) The final document, written by Ingrim with Johns’ assistance, states that the construction and position of the fisheries demonstrates savvy engineering expertise:

These channels have been made by removing loose stones and portions of the more solid rocks between the ridges and the lowest places, also by constructing low wing walls to concentrate the stream. At suitable places are erected stone barricades with timber built in so as to form openings of from one to two feet wide, behind these openings were secured, long narrow bag nets made of strong rushes.

Another amateur historian, Thomas Worsnop, published Ingrim’s map in his 1897 book, The Prehistoric Arts, Manufactures, Works, Weapons, etc., of the Aborigines of Australia. Worsnop also described “the remains of an old aboriginal camping-place, the name of which is Narrarrabeen, consisting of about twenty stone foundations, of horseshoe form, from four feet to seven feet in diameter, and opening towards the east, a point from which the wind rarely blows.” These stone foundations appeared to be the remains of constructed homes, further challenging the colonial perception that all Aboriginal people were nomads.

Essential to the map’s accuracy—providing Ingrim with information on the construction of the canals and stone traps, as well as the traditional place names—was Thomas White, a Gunditjmara local who was born in the early 1830s near Lake Condah, where he resided his entire life. In 1867 the Church of England established a mission by Lake Condah, sequestering the area’s remaining Aboriginal population to this single site. The mission enforced a harsh rule over its residents, including White (a name surely bestowed by the circumstances), where rations and work certificates were withheld to maintain segregation. White was given little credit for the map aside from a single mention in Worsnop’s book.

Documents such as Ingrim’s map and Robinson’s journal are called the first official records of the Lake Condah fisheries, and in one sense this is true. But that designation denies the record-keeping practices of Indigenous oral history that informed White. White’s knowledge of the fisheries and the adjacent homes, passed down through generations, is what lends Ingrim’s records their authority.

After nearly a century of neglect, Lake Condah suddenly became the subject of renewed interest in the late 1970s, due to a survey of the fisheries conducted by Peter Coutts of the Victorian Archaeological Survey. Over the following decade, The Age, Victoria’s state newspaper, frequently reported on Lake Condah. The first piece ran in 1981 and painted a vivid picture of Gunditjmara life by the lake: “Living in a small stone house in a village of similar houses…cooking on a hearth made of basalt stones under a low roof…It’s a far cry from the traditional picture of the Australian Aboriginie as a nomadic hunter and food gatherer.” Later studies would question this description of the “village” and the precise social function of the stone houses, but the ingenuity of the canal system itself went undisputed.

The following year, the Indigenous Australian writer and historian Bruce Pascoe, also writing in The Age, revered this “civilization of the original inhabitants,” noting that “archaeologists couldn’t fully understand the operation of the canals until they saw them functioning during a flood in 1977 when the whole grand design became clear.”

Things moved quickly from there. In 1985 Ingrim’s map resurfaced in a paper for the local anthropological society. That same year, as part of the state of Victoria’s 150th birthday program, Lake Condah was restored as a tourist attraction run by the local Gunditjmarans. In 2007 a native title determination was granted, giving inalienable land rights to the Gunditjmara community. The lake was reflooded in 2010 to repair the damage done by the drainage scheme of the late 1800s (which Ingrim had worked on); since the flooding, water birds including coots, black swans, and brolgas have returned to the area. And in 2017 the Budj Bim cultural landscape was officially placed on the pending list of UNESCO World Heritage sites, the first Australian site to be so placed exclusively for Aboriginal cultural value.

Pascoe, a leading voice for greater recognition of Aboriginal heritage who dedicated a large part of his 2013 book Dark Emu to Lake Condah, was the first to forewarn in 1982 of the tensions that a site like the fisheries were likely to produce among local white farmers, “many of whom refuse to recognize that the ruins of Aboriginal settlement exist in the area.” The remains of stone houses and fish traps, often found on privately owned land, were a cause for concern for these white landowners. “They fear that their farms of four or five generations’ standing might be threatened by land rights claims,” he wrote.

It was more than simply fear. As Robert Hughes wrote in his epic history of Australia’s founding, The Fatal Shore, racism has played a foundational role in Australian character since the arrival of the First Fleet, beginning with the first convicts:

Galled by exile, the lowest of the low, [the convicts] desperately needed to believe in a class inferior to themselves. The Aborigines answered that need. Australian racism began with the convicts, although it did not stay confined to them for long; it was the first Australian trait to percolate upward from the lower class.

People who disdain the notion of Indigenous land rights often deploy the term “hunter-gatherer” in retort. The term posits that a nomadic people, being forever on the move, had no conception of land ownership to begin with, leaving Australia free for the taking. It is also why a site like Lake Condah was dismissed for so long, despite its appearance in early records.

Keith Windschuttle, the writer and editor of the Australian conservative journal Quadrant and a staunch defender of colonization, uses the phrase “hunter-gatherers” repeatedly in his polemics to persuade his reader of Aboriginal inferiority. In a 2018 Quadrant essay defending the celebration of Australia Day (the date has caused national debate because it marks the beginning of white settlement), Windschuttle openly celebrated “the dispossession of the Aboriginal people and the replacement of their hunter-gatherer way of life with a cultural, political, and legal system far more sophisticated and powerful.” After several paragraphs in which he refutes the extent of the violence perpetrated by the first white settlers, Windschuttle ends by stating that “to expect the continent of Australia to remain in the hands of hunter-gatherers is naive.”

Windschuttle has been rightly dismissed for possessing “astonishing ideological blindness,” as Robert Manne wrote in the magazine The Monthly, and Windschuttle’s self-published three-volume work The Fabrication of Aboriginal History has been widely criticized for inaccuracies and selective research. Yet his view that Indigenous people have no claim to land rights is not uncommon. Australian records have often obscured or omitted the facts when the “hunter-gatherer” premise is proven to be inconveniently false. Thanks to Windschuttle and those who think like him, that blindness continues today.

National recognition of sites like Lake Condah dramatically reframe the reductive portrait that white Australians have long painted of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. This is why people like Denis Rose, a senior Gunditjmara elder, one of the advocates for Budj Bim’s heritage listing, and the area coordinator at Lake Condah, are working so hard for the site to be officially recognized. “We have plans to build an eel-processing facility that will contribute, we hope, to economic development and also that important education role,” Rose told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) in 2013. As well as revitalizing the community’s relationship to land, Lake Condah’s development will hopefully establish the fisheries—a site many Australians may still not know—as one of the country’s key historic landmarks.

In 2007, in an op-ed for The Age, Pascoe vented his frustration toward Australia’s ongoing cultural amnesia regarding sites like Lake Condah. During a radio interview with Pascoe, two journalists had suggested that Pascoe’s “reference to stone houses, grain harvests, and fish aquaculture was somehow a fabrication or at best a distortion of history.” Pascoe chastised the country for its educational failures, allowing otherwise intelligent Australians to assume “that a society capable of the engineering to tunnel into rock and build sophisticated structures must have been advised by an Englishman.” (While the earliest dating of the site confirms that white colonists could not have influenced the design, the fisheries were improved upon at a later date, which opponents argue was by way of Western influence.) Pascoe continued:

A cynic would say we hide behind a myth of the hapless Aborigine wandering aimlessly over the continent and failing to resist European invasion so that we might validate our occupation of the continent. But I think that, while the myth may have grown from the source, we persist in believing it because our education has failed us.

There is a name for this Australian cultural amnesia: the Great Australian Silence. Anthropologist William E.H. Stanner coined the phrase in 1968 to describe the “cult of forgetfulness practiced on a national scale,” or what he later called “a sightlessness towards aboriginal life.” The foundation of this great silencing of historical knowledge, Pascoe wrote, is an abandonment and dismissal of historical records. “Young Australians,” he pleaded, “thank your parents for their earnest response to indigenous disadvantage, but then go back to the early archives—you’re in for a surprise.”

Beyond the archives are the people still living by Lake Condah, still tending to the fisheries, and still passing their knowledge down over generations. Eileen Alberts, a Gunditjmara elder and chair of Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation, told the ABC that the site “gave us our food, it gave us our shelter, it was the centerpiece of our community. It’s part of who we are.” Yet the archives are a vital resource, made all the more significant when they include the voices of people like Alberts and Denis Rose, and Thomas White before them, and millions of others in between left unheard.

Read more on the history of water and how humans use it in our Summer 2018 issue, Water.