Slave Cabin Interior, Maryland, by William Earle Williams, 2008. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the artist in memory of Lonnie and Lucille Barksdale.

Frances Anne Kemble had many admirers, some famous, some not. They agreed generally that the British actress, also known as Fanny, was brilliant, engaging, and excitable, as well as difficult in the manner of nineteenth-century women who earned that reputation simply by voicing an opinion. She was a person especially full of opinions—fond of Dante and horseback riding, suspicious of social convention—and eager to share them. Her daughter Sarah called her “the most stimulating companion I have ever known”—and “the most goading.” Kemble’s friend Henry James wrote that she was “like a straight deep cistern without a cover, or even, sometimes, a bucket, into which, as a mode of intercourse, one must tumble with a splash.”

Of the many splashes Kemble herself created, the biggest was a journal kept in the winter of 1838–39. She and her family had left the cold of their home in Philadelphia for a four-month stay on the Georgia coast, where they were surrounded by the vast plantations her husband had inherited, along with nearly one thousand enslaved people. Kemble opposed slavery—“for I am an Englishwoman,” she wrote, “in whom the absence of such a prejudice would be disgraceful.”

The actress, who belonged to a famous family of British dramatists, had met Pierce Mease Butler during an American tour that began in Manhattan in September 1832; Kemble was introduced to Butler in Philadelphia later that fall. “He is, it seems, a great fortune,” she noted. “Consequently, I suppose (in spite of his inches), a great man.” They married in 1834. The original Pierce Butler had signed his name to the Constitution and established one of the largest rice-growing enterprises on the southeast coast, while his grandson was a shiftless socialite who, two years after marrying Kemble, claimed his inheritance. When they wed, Kemble wrote, “I knew nothing of these dreadful possessions of his.”

Butler’s was the “second-largest slave-owning empire in Georgia” when Kemble visited, according to her biographer Catherine Clinton. Kemble had repeatedly asked her husband to see the South—pleas he resisted until 1838, when business brought him down to Georgia. Kemble and their two children joined him. Kemble wanted to see slavery with her own eyes, and Butler thought she might be brought around by learning the realities of a working plantation. They had already argued over slavery: when Kemble published Journal of a Residence in America, diaries of her voyage to and initial observations of the country, in 1835, Butler persuaded her to excise an antislavery essay from the journal.1

In Georgia, the political became horrifyingly personal for Kemble. She realized how much the peculiar institution abetted her own lifestyle. The actress sent her observations in a series of letters to a friend up north, describing in quotidian detail the conditions of the enslaved people. “Inquiry into their mode of existence will form my chief occupation,” she wrote upon arrival.

Kemble was in the exquisitely weird position of being both the plantation master’s wife and a person exploring a form of solidarity, however uneasily, with the people he owned. She established herself as a kind of liaison between the enslaved people and her husband, whom she entreated on their behalf—for better clothing and bedding, less work, and so on. “My conscience forbids my ever postponing their business,” she wrote in one letter. “By their unpaid labor I live—their nakedness clothes me, and their heavy toil maintains me in luxurious idleness. Surely the least I can do is to hear these, my most injured benefactors.” At one point she simply makes a list of the names of some of the women on the plantation and the physical ravages of slavery on them, including how many children they had lost. She also starts teaching a young man named Aleck to read. It’s against the law, but as Kemble notes, any legal trouble would redound to her own master: her husband. “If I were a man,” she wrote, “I would do that and many a thing besides, and doubtless should be shot some fine day from behind a tree by some good neighbor, who would do the community a service by quietly getting rid of a mischievous incendiary.”

She heard the complaints of the enslaved people on the plantation and tried to intervene, and she paid them money for the work she asked them to do for her. But most of all, she watched. Kemble focused especially on the abuses, sexual and otherwise, inflicted on the women on the plantation. The literary scholar Diane Roberts writes that Kemble’s dispatches are “the most explicit white text on slavery as institutionalized rape.” In her 1975 book Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape, Susan Brownmiller cites a colloquy between an enslaved woman named Sophy and Kemble, who asks why Sophy didn’t resist an assault. It’s a dumb question, but part of what makes Kemble a good narrator is that she’s not shy about conveying these moments. Sophy tells Kemble, “What use me tell him no? He have strength to make me.”

Kemble’s Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation in 1838–1839 has been compared to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The books do share a tone of moral emergency, but the journal had none of the novel’s galvanizing effect, largely because it was published twenty-five years after Kemble’s visit, in the midst of the Civil War. She had spent the intervening years trying to save her marriage and regain custody of her children, failing on both counts. (Butler fought for full custody after Kemble traveled to Europe for work; in their settlement, he got the children for ten months of the year and she had them for two.) Even before the trip to Georgia, Kemble had chafed against her husband’s attempts to control her—she ran away from him for the first time just four months into their marriage—and the Southern misadventure helped push them toward a messy and public divorce. She suspected him of infidelity, and in 1850, Butler circulated a remarkable pamphlet defending himself against that charge and many others besides, complaining that his wife “held that marriage should be companionship on equal terms.” While still married to Butler, Kemble entertained offers from the abolitionist publisher Lydia Maria Child to release the Georgia journal. Butler was so fearful of the idea that when Kemble wrote a letter to Child declining the offer, he intercepted it and hid it in a drawer.

The divorce was finalized in 1849, but Kemble continued to sit on her account. She finally decided to publish it in 1863, hoping to sway opinion on the Civil War in England, which was considering recognizing the Confederacy. By then the Journal was too little, too late to be useful to the Northern abolitionists who had been circulating it among themselves for decades while trying to get Kemble to release it. Missing its chance to become propaganda, the book was of no use to the Southerners writing the first drafts of antebellum history after the Civil War—they thought of Kemble as a scurrilous interloper.

While the Butlers’ divorce dragged on, life on the Georgia plantations continued as before—until it didn’t. In 1859, on the eve of the war and two decades after Kemble’s visit, her ex-husband sold half of the people from his plantations in what is thought to be the largest slave auction in American history.

I attended a ceremony in Savannah observing the 160th anniversary of that sale in March. During the 1859 auction, 436 people were put up for sale to buyers around the country. At the anniversary event in 2019, 436 chairs were set up, empty, with two more to the side holding wreaths: one was dedicated to Mortimer Thomson, a Northern reporter who had chronicled the event, and the other to Fanny Kemble.

The fact that Fanny Kemble’s name is still on Georgians’ lips surprised me. In part that’s because her book is, as an antislavery tract, tainted by antiblack prejudices, which Kemble is not shy about relating. The callousness with which she initially makes these observations, and the tenderness she conveys toward the end of her visit, suggest to the reader the sense of an arc, an aspect that’s creditable in fiction but stranger in history. Meanwhile, the people enslaved on the Butler plantations were legally kept from literacy and are relatively silent on the written page; it wouldn’t be until the next century that their own arcs—and the manifold daring ways they resisted slavery—would begin to be explored in depth by scholars. Particularly in light of this evolution in the study of slavery, the story of Fanny Kemble raises the problem of the white savior narrative. Of course, Kemble didn’t successfully resist much. Her Georgia Journal is a long howl of frustration: she petitions her husband so many times on behalf of the enslaved people that he tells her to stop asking. She can’t save anyone from slavery; she can’t even save her own marriage. In Georgia, Kemble found a kind of anguish at being—maybe for the first time in her privileged life—unable to make much difference at all.

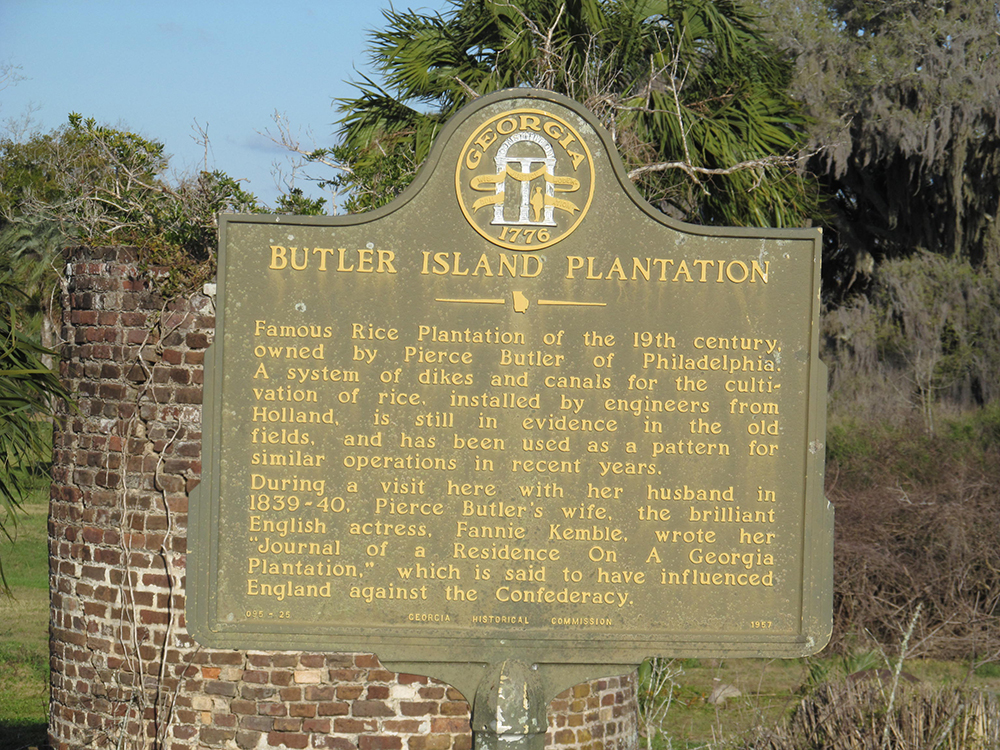

Butler Island, where Kemble spent most of her time in Georgia, today bears little evidence of its awful past, beyond the name and the landscape itself. Lodged in a river delta south of Savannah, the marshy land was converted in the eighteenth century to a rice plantation by enslaved people who cut arrow-straight canals through it and built levees around its edges. (The Butler holdings also included a cotton plantation on nearby Saint Simons Island.) It’s now a state-run wildlife area. The island never exemplified the moonlight-and-magnolias image often associated with Southern plantations. Butler owned from afar, hiring local white overseers to manage the daily operations; the malarial humidity kept all but the poorest white people away from the sweltering summers on the coast. The numbers reflect just how absent white people were from this landscape. In the two coastal counties where Butler held property, enslaved black people made up 80 percent of the population in 1840.

In the beginning of her Journal, Kemble holds out the possibility that she will find “mitigations” that might soften her view of slavery. She is baldly racist, depicting the people who live on the plantation as little more than an undifferentiated mass, disgusted by their living conditions and infatuated with their physical features—lips, nose, hair. Such rhetoric falls away as Kemble’s involvement in the life of the plantation deepens, and her letters begin to explore all the grotesque social arrangements that slavery begets. She observes her young daughter say “something about a swing, and in less than five minutes headman Frank had erected it for her, and a dozen young slaves were ready to swing little ‘missis.’…Think of learning to rule despotically your fellow creatures before the first lesson of self-government has been well spelled over! It makes me tremble.” She describes beatings incurred and injuries sustained, along with subtler degradations. One day she and Jack, a young enslaved man, are riding on horses and come across a burial ground trampled by cattle, where a fence has been erected “round the graves of two white men who had worked on the estate,” separating and preserving them apart from the rest of the graves.

They were strangers, and of course utterly indifferent to the people here; but by virtue of their white skins, their resting place was protected from the hoofs of the cattle, while the parents and children, wives, husbands, brothers and sisters, of the poor slaves, sleeping beside them, might see the graves of those they loved trampled upon and browsed over, desecrated and defiled, from morning till night. There is something intolerably cruel in this disdainful denial of a common humanity pursuing these wretches even when they are hid beneath the earth.

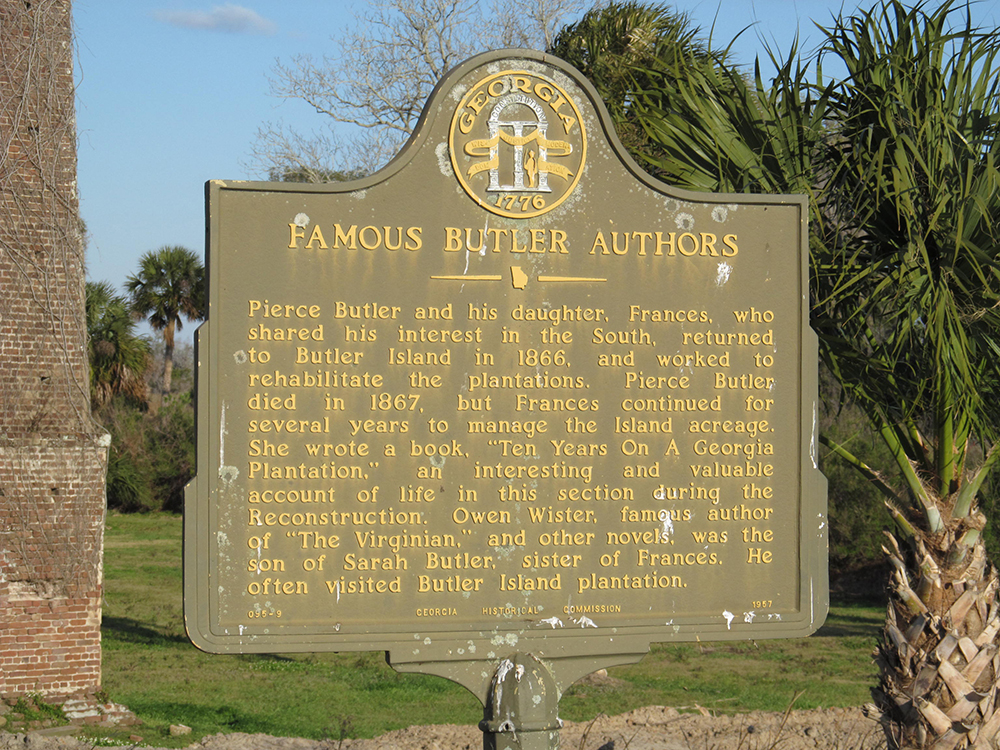

The burial ground was on Saint Simons Island, which was occupied by Union forces during the Civil War and served as a haven for black people freed from slavery. Nearby Butler Island quickly fell into disrepair. Following the war, Pierce Mease Butler returned to Georgia to try to revive the island’s rice plantation, bringing along his daughter Frances Butler Leigh, or Fan, as she was known—who, following the family custom, made a memoir of her time there, published in 1883. (Pierce Butler died in Georgia, of malaria, in 1867.)

If Kemble’s book represents one political tradition, her daughter’s is another affair entirely: an early attempt at rewriting a history that emphasized the nobility of the white slaveholding class, the idea of slavery as a civilizing force, and so on. Even its title, Ten Years on a Georgia Plantation Since the War, demonstrates its challenge to the authority of her mother, who spent only four months in Georgia. While the mother positioned herself as an outsider debunking the white South’s myths about itself and its peculiar institution, the daughter uses her status as an insider to try to reinscribe those myths just as they’re in danger of being destroyed. Diane Roberts explains that this progression echoed a trend in national literature—whereas books revealing the horrors of slavery were popular prior to the war, white readers of the postbellum period began to embrace texts sketching a romantic portrait of the ruined South.

In her temperament and her loquaciousness, Fan closely resembled her mother, according to several observers—including Kemble and Butler’s other daughter, Sarah, who was more Kemble’s political heir. Sarah, who lived in Philadelphia, opposed slavery; according to Clinton, Fan “complained that her sister went so far as to refuse to ‘receive a Southerner in her house.’ ” Again echoing the national narrative, the intrafamily tensions continued long after the country had been formally reunited.

Returning to Georgia in 1866, Leigh found the white people dispirited and the black people in need of direction, grateful for the return of their beloved patrons. She related an exchange between an agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau (“a miserable creature”) and a man named Bram, who had been sold in the Savannah auction in 1859 but had returned. “Why, Bram,” the agent asks, “how can you care so much for your master—he sold you a few years ago?” In Leigh’s telling, Bram is magnanimous, recalling his words to Butler: “Master, if you will keep me I will work for you as long as I live, but if you in trouble and it help you to sell me, sell me, master, I am willing.” Leigh also attended the funeral of James Hamilton Couper, a major Saint Simons Island slave owner who was well-respected among his peers—the benevolent gentleman planter of myth to whom freed people would willingly return. In Leigh’s recollection, his coffin is carried by “four old family negroes, faithful to the end.” As it’s carted off, Leigh says to herself, “Someday justice will be done, and the Truth shall be heard above the political din of slander and lies, and the Northern people shall see things as they are, and not through the dark veil of envy, hatred, and malice.”2

Leigh’s book gave early postbellum white historians further reason to keep her mother from the canon. Southern history doyen Ulrich B. Phillips, author of the influential Life and Labor in the Old South (1929), dismissed the Journal as “a monotonous view of the seamy side, and an exhibit of the critic’s own mental processes.” Leigh’s Ten Years, by contrast, “refutes her mother’s argument and poses experience against theory as to Negro quality, white responsibility, Pierce M. Butler’s character, and the regime on Butler’s Island.” In 1960 a local historian named Margaret Davis Cate published a short article in the Georgia Historical Quarterly called “Mistakes in Fanny Kemble’s Georgia Journal.” Relying for evidence on Leigh’s Ten Years, Cate argued that Kemble spent the quarter century between her Georgia visit and the publication of her Journal thinking up ways to give dramatic heft to what must have been an uneventful visit—“and no one could know better the value of drama than this actress-author,” she wrote.

The following year, the centenary of the outbreak of the Civil War, Knopf published an edition of the Journal that brought renewed attention to Kemble—in part via her detractors, the same kind of white Southerners who had spent the intervening century constructing the mythos of the Lost Cause and who were then contending with the demands of the civil rights movement. Despite its long period of obscurity, and despite protestations from historians like Phillips and Cate, Kemble’s portrait of slavery on Butler and Saint Simons islands is the one that has come to be taken seriously by scholars.

In 1988 the New York Times reporter Ronald Smothers visited Roswell, Georgia, on the occasion of the publication of Major Butler’s Legacy: Five Generations of a Slaveholding Family. Written by Malcolm Bell Jr., the book is the definitive volume on the Butler family. Roswell, now a suburb of Atlanta, had been founded by Roswell King Sr. after he retired from a long career as the overseer of Butler’s plantations. He was succeeded in the job by his son Roswell King Jr. Both figure into Kemble’s Journal as violent disciplinarians who fathered a number of children with enslaved women. One of the women King Jr. raped was Betty, the wife of Frank, the head driver. Visiting Roswell to give a reading, Bell had more success communicating these stories to a white Southern audience than Kemble ever did. Smothers noted that “in more recent years” white locals were inclined to dismiss Kemble because—and here’s a revealing bit of gothic fantasia—Kemble was angry at being “spurned” herself by Roswell King Jr. “Mr. Bell was received a lot better than Fanny Kemble ever would have been,” an attendee said. “We’ve come a long way since then.” It’s worth noting, too, that Bell was a Savannahian of good old stock, whereas Kemble was here a while and then left.

The 1859 auction, occasioned by Pierce Butler’s gambling debts, took place over a couple of days at what was then a racetrack on the outskirts of Savannah. The 436 people put up for sale accounted for about half the enslaved people on the Butler plantations. The sale came to be called the Weeping Time because it rained throughout. The skies then cleared, and people who had lived their whole lives on the Georgia coast were taken all over the country. Butler sailed for Europe. (Mortimer Thomson, the New York reporter who posed as a buyer to get into the sale, published his collected observations in a 1863 pamphlet called What Became of the Slaves on a Georgia Plantation?, subtitled “A Sequel to Mrs. Kemble’s Journal.”)

Kemble was by then long gone. After her separation from Butler, she returned occasionally to acting, giving Shakespeare readings in London and New York, and bought a house in Lenox, Massachusetts. She began writing a column for The Atlantic called “An Old Woman’s Gossip”; published more memoirs; and in 1889, at the age of eighty, published her first novel, Far Away and Long Ago. She died in 1893.

She never returned to Georgia. In a short, chilling afterword she wrote for the Journal when it was published in 1863, Kemble mentioned that the only person she had seen from the plantations in the intervening years was Jack, whom she was particularly close to. He had fallen ill and was sent to convalesce in Philadelphia—where, prior to the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, he could have tried to gain his freedom. Out of concerns that he “should be enlightened as to this fact by some philanthropic abolitionist,” Jack’s handlers kept him shut away in the upper floor of a house, and Kemble was allowed to see him only after promising to keep her mouth shut. In her afterword, she reflects on a conversation she overheard in Georgia between overseers on the topic of traveling north with enslaved people. The key, Roswell King Jr. explained, is to keep their children in the South—that way they won’t be persuaded to run. After the war, in a letter to a friend, Kemble wrote of the Butler plantations, “There must be almost a new heaven and a new earth throughout the whole of that land before it can recover from the leprosy in which it has been steeped for nearly a hundred years.”

Part of the allure of the Fanny Kemble story to historians—she has been the subject of a few biographies—is the way in which it serves as a microcosm of a larger sectional division. Hers and Butler’s is a house almost literally divided against itself, a split repeated after the war when one daughter—but not the other—becomes a full-throated Confederate nostalgist. It’s positively cinematic. And it can draw the attention away from the biggest tragedy of all, which is having to rely on the accident of Fanny Kemble’s time in Georgia to learn of life on the Butler plantations. So many others—scores more than 436—could have said so much more, but their voices occupy a much smaller place in the written record. Instead there is this brilliant, racist British actress turned author, a visitor to Georgia by only the strangest and most contingent circumstances, who left behind such a vibrant, clear-eyed, and morally urgent document that to imagine the history of the Butler empire without it feels a bit like standing at the edge of a canyon and worrying about tripping. What if there were, instead, nothing?

1 The book nonetheless didn’t escape controversy; it’s possible Kemble was still mastering her voice. Clinton writes, “Passages intended as lighthearted, satirical musings came across in print as rather heavy-handed.” While commending the “vivacity of its style” of the 1835 Journal in a review in in the Southern Literary Messenger, Edgar Allan Poe noted, “A female, and a young one too, cannot speak with the self-confidence which marks this book, without jarring somewhat upon American notions of the retiring delicacy of the female character.” In her own diary, Queen Victoria described the book as “full of trash and nonsense which could only do harm.” ↩

2 Clinton cites a later critic who observed that “to contrast Fan’s book with her mother’s was to compare The Swiss Family Robinson to Wuthering Heights.” ↩