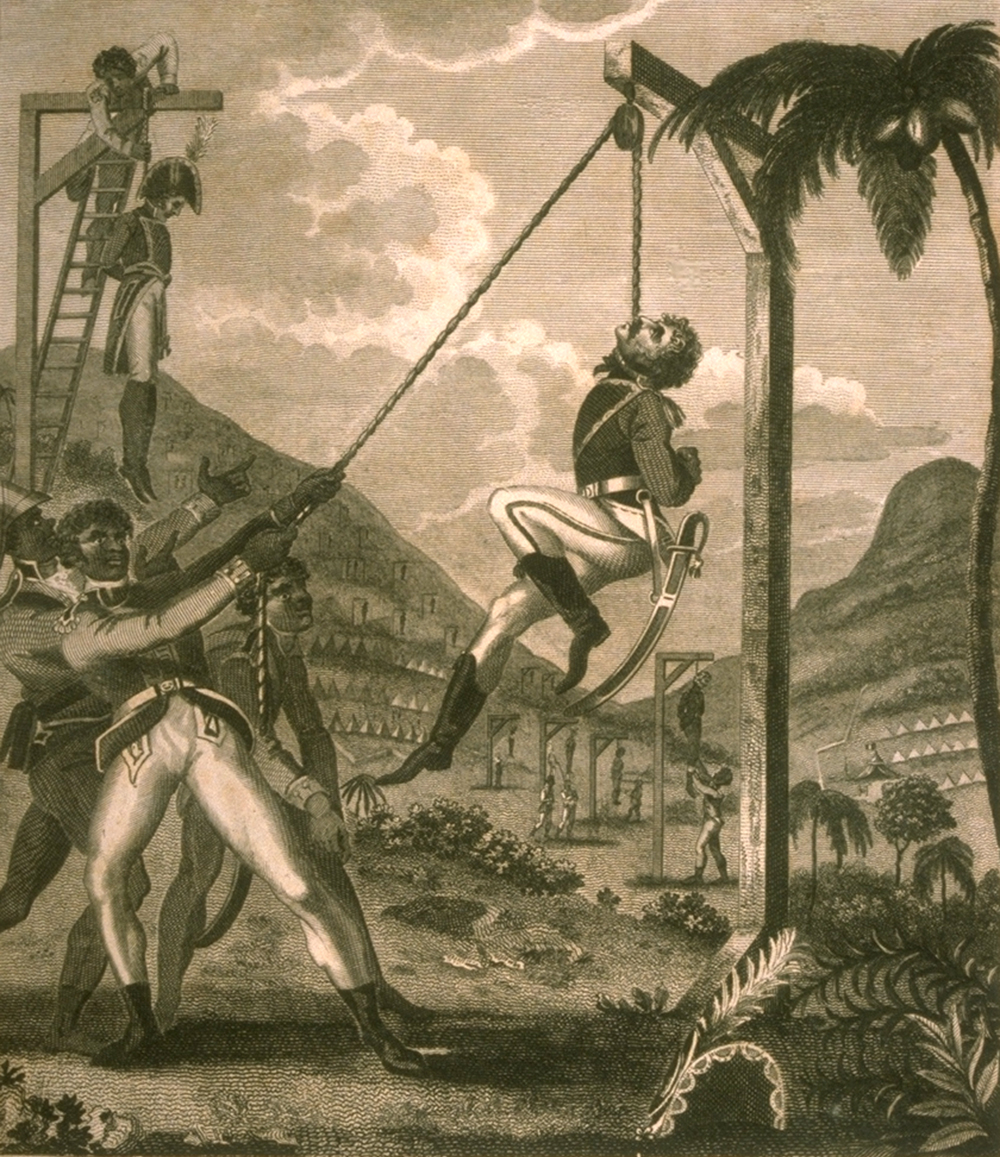

Both during and after the Haitian Revolution, the most widely circulated images of the thirteen-year violent conflict that remade French Saint-Domingue into independent Haiti depicted Black people killing white people. The 1805 book An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti, by Marcus Rainsford—an army officer who had been stationed in Saint-Domingue during the British occupation of the island—included a representative, and frequently reproduced, picture from the genre: Black revolutionaries stringing up white soldiers on a hillside. This Black-on-white violence is described with the words “Revenge taken by the black army for the cruelties practiced on them by the French.” (The book also features a now iconic portrait of Toussaint Louverture.)

Rainsford’s account, like the caption, is generally sympathetic to the revolution and its leaders’ cause of ridding the island of slavery forever. Other less well-known illustrations in the volume support this perspective by offering graphic images of the violence that the French army exerted over the revolutionaries. One such engraving shows Cuban bloodhounds—which the French military notoriously trained to “eat the blacks”—attacking a terrified Black mother and child; another image illustrates the infamous drownings perpetrated by the French in their attempts, as the inscription reads, at “exterminating the Black Army.”

Rainsford had described the genocidal operation the French waged from 1802 to 1803 against the Black revolutionaries in the following dire terms:

The [French] government at this period…assumed a complexion more sanguinary and terrible than can be conceived among civilized people…In attempting to disarm the black troops…the most barbarous methods were practiced, shiploads were collected and suffocated in the holds. In one instance, six hundred being surrounded, and attempting a resistance, were massacred on the spot; and such slaughters daily took place in the vicinity of Cap-Français, that the air became tainted by the putrefaction of the bodies.

Although the British had been at war with France, the officer’s compassion for the Haitian revolutionaries’ utter desperation was unusual in the era. Most accounts of the revolution were stamped with overarching sympathy for the white colonists and deep horror at the very idea that enslaved Africans might kill their “masters” in order to free themselves.

Around 75,000 white French people died during the Haitian Revolution, a dramatic contrast to the more than 350,000 Black people who were killed. Yet it was rare in the nineteenth century to see any acknowledgment of this disparity. Portraying Black people as perpetrators of violence rather than its victims—a tendency that persists in many parts of the world to this day—functioned as a deliberate distraction from the everyday depredations of slavery and the atrocities that both the French colonists and the French army had committed in Saint-Domingue. The visual history of the Haitian Revolution can tell us a lot about how repeated exposure to representations of Black people in aggressive postures smothers histories of white violence and turns our gaze away from Black death. Because these images have become the default—even in contemporary accounts that acknowledge the Haitian Revolution as the most radical attempt in world history to create universal liberty and equality—they have directly contributed to the stereotype that Black rage is the source of societal violence rather than an aching response to it.

Immediately after the beginning of the Haitian Revolution in August 1791, newspapers around the world printed tales of the widespread deaths of whites. “The news from Saint-Domingue is horrifying,” reported the Paris-based Le Courrier extraordinaire on October 30. “Two hundred plantations on fire; three hundred whites massacred.” Historical narratives tended to characterize the revolution in much the same way. In the two-volume Saint-Domingue, ou Histoire de ses Révolutions, anonymously published around 1804, the year the revolution ended, a frontispiece reduced the rebellion of enslaved people to a simple race war: “General revolt of the negroes. Massacre of the whites.”

In 1793, when the capital of the colony, Cap-Français, was set ablaze by Black revolutionaries, paintings depicting the fires told tales of property destruction designed to produce more sympathy for the lost buildings than for the human beings who had been tortured and enslaved within them. Two of the most famous examples, by J.L. Boquet and Swebach-Desfontaines, used the specter of Black vengeance to paint the colony’s nearly forty thousand French residents as innocent victims who had lost all their worldly possessions as they fled the smoke and ashes en masse.

References to the fires in Saint-Domingue and the proliferating images of Black people killing white people were just as ubiquitous in literary fictions of the revolution. In 1802 the French novelist and playwright René Périn published one of the first French-language novels about the Haitian Revolution, L’Incendie du Cap, ou Le règne de Toussaint-Louverture (The burning of Cap, or The reign of Toussaint Louverture). Clearly sympathizing with the planters, in the preface Périn opined, “I am going to take us into the middle of the city of Cap, to look there for the victims of this atrocious negro, and offer a portrait upon which, reader, you may be forced to shed many tears!!!” It was also in 1802 when Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother-in-law General Charles Leclerc landed in Saint-Domingue with a military expedition that eventually brought around eighty thousand French soldiers to the island. Leclerc’s mission was not only to pave the way for the reinstatement of slavery, which the French National Assembly had abolished in 1794, but to restore the authority Bonaparte felt Toussaint Louverture had usurped when he named himself governor-general of Saint-Domingue for life in 1801.

Périn’s tale would never become as famous as Victor Hugo’s anti–Haitian Revolution novel Bug-Jargal (1826) or Alphonse de Lamartine’s melodramatic antislavery verse drama Toussaint Louverture (1850). Yet the frontispiece to The Burning of Cap remains one of the most recognizable images of the revolution.

This unremarkable novel circulated widely enough that a copy of it reached independent Haiti, where it fell into the hands of future king Henry Christophe, then head of the Haitian army. On December 13, 1805, noting that this “petite brochure” had arrived via a merchant ship from the United States, General Christophe sent it with a warning to Emperor Jacques I (Jean-Jacques Dessalines), who led Haiti to independence in 1804:

The contents of this brochure leave no doubt about the views of our enemies, since they do not even accord us the title of men, judging that we are not worthy of the liberty that we enjoy, that we conquered using the strength of our arms, and that no power on earth can ever take from us! But let them come, and I will give them new proof.

Despite his dogged insistence that independence was the righteous outcome of Haiti’s fight to end forever the state of war that is slavery, the Haitian general was well aware that narratives like The Burning of Cap were designed to refocus attention on the white people who died during the conflict.

Tales of “white massacre” had already led some previously sympathetic French writers, such as Olympe de Gouges, to argue that the rebellious slaves and free people in the colony were equally as cruel as the white colonists. Shortly after the Haitian Revolution began, de Gouges—who would be sent to the guillotine by the Jacobins in 1793—wrote that the revolutionaries had paradoxically justified the actions of the colonists by imitating their “most barbaric and atrocious tortures.” Those already ill inclined to support the Haitian Revolution, like the writer François-René de Chateaubriand, son of a slave trafficker, characterized the Black rebels as indefensibly out for blood and undeserving of the world’s sympathy. In his 1802 work The Genius of Christianity (Le Génie du christianisme), Chateaubriand implored, “Who would dare to plead the cause of the Blacks after the crimes they have committed?”

Lamenting that for years Haitians had not been able to counter such spurious claims, in 1814 the Baron de Vastey, King Henry Christophe’s most prominent minister, wrote in his famous pamphlet The Colonial System Unveiled (Le Système colonial dévoilé): “The friends of slavery, those eternal enemies of the human race, have made all the presses of Europe groan for centuries in order to reduce the Black man below the brute.” He proclaimed, “Now that we have Haitian printing presses, we can reveal the crimes of the colonists and respond to even the most absurd calumnies invented by the prejudice and greed of our oppressors.”

In his widely read exposé, Vastey painstakingly described how the colonists of Saint-Domingue had practiced some of the cruelest tortures on enslaved people in the Atlantic world. These included burning and burying them alive; severing limbs, ears, and other body parts; bleeding the enslaved to death; and nailing them to walls and trees, along with various forms of sexual assault, which Vastey called “crapulous debauchery.” Detailing the horrific crimes of a planter named Gallifet, Vastey reported that “he was accustomed to cut the hamstrings of his slaves” and that his plantation was well-known for its dungeons, where enslaved people “perished lying in water, by a cold and dampness which suppressed the circulation of their blood.”

Vastey’s descriptions did lead some foreign readers to wonder who would dare plead the cause of the white colonists after the crimes they had committed. A review of the pamphlet in the British Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine in 1818 damningly concluded, “In reading over the tract before us we have doubted whether we were in the society of men or of wild beasts; but a little reflection easily convinced us that the brutes of the field could not act as the monsters we have been placed in company with.” Still, such affirmations of French barbarity did little to disrupt the general arc of the sympathy-for-whites trope that abounded in nineteenth-century literature and art of the Haitian Revolution.

Today’s French government continues the long-standing tradition of painting France as the champion of human rights, rather than as one of the world’s worst offenders when it comes to slavery and colonialism. But maintaining this narrative requires ignoring, downplaying, and disputing a wealth of historical sources, produced both in Haiti and the broader Atlantic world, that testify to the crimes against humanity the French committed in Saint-Domingue.

Multiple eyewitnesses from the revolutionary era confirm dead Black bodies piled up in every corner of the colony. Such informants second Rainsford’s report that under General Leclerc and his successor General Rochambeau, the French military had attempted to carry out genocide. Leclerc himself confirmed it when he wrote Napoleon Bonaparte on October 7, 1802, “Here is my opinion on this country: We must destroy all the blacks in the mountains—men and women—and spare only the children under twelve years of age. We must destroy half of those in the plains and must not leave a single colored person in the colony who has worn an epaulette.”

This brazen depravity played out directly in the public eye. A U.S. merchant recounted in an 1803 article for the Philadelphia-based Literary Magazine, and American Register that in November 1802 he witnessed “scenes that bear the deepest tinge of barbarous atrocity.”

Seven or eight hundred blacks and men of color were seized upon in the streets, in the public places, in the very houses, and for the moment confined within the walls of a prison. Thence they were hurried on board the national vessels lying in the harbor, from whence they were plunged into eternity.

As a result of all of this “premeditated barbarity,” the merchant concluded, “the billows now washed these unfortunate victims to the shore, floating with their eyes, as it were, turned toward heaven, they seemed to demand vengeance on the author of their untimely death.”

Even some French military officers were horrified. General Jean-Pierre Ramel (the younger), who served under Rochambeau, acknowledged that the French were indiscriminately massacring Black people, including those not in open rebellion:

Who were the men whom we drowned in Saint-Domingue? Blacks who had been captured as prisoners on the fields of battle? No; Conspirators? Even less so! Nobody was convicted of anything: because of a simple suspicion, a report, an equivocal word, 200, 400, 800, up to 1,500 blacks had been thrown into the sea. I saw this happen, and I complained about it.

Despite an abundance of firsthand accounts proving the contrary, contemporary scholars sometimes contribute to the image of a revolutionary Saint-Domingue littered with white bodies by repeating the claims of the era’s reactionaries, who painted the Haitian Revolution as a time when Black people overwhelmingly massacred whites, including pregnant women and children. Recently, using the phrase “Caribbean genocide,” historian Philippe Girard concluded that from 1802 to 1804, “with few exceptions, those who perpetrated the genocide were former slaves, while most victims were former slave owners and soldiers supporting slavery.” This claim is in direct contradiction with history. The only people who ever committed genocide on the island of Saint-Domingue were the Spanish. And the only ones who ever attempted it again were the French.

The Bulgarian-French philosopher, historian, and literary critic Tzvetan Todorov has referred to the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Spanish conquest of the Americas (encompassing South America, Mexico, and the Caribbean)—whereby 90 percent of the indigenous population was exterminated by the Spanish through a fatal combination of war, displacement, and disease—as the “greatest genocide in human history.” The torturous labor conditions in the colony under French rule, which began in 1697, led to an extraordinarily high death rate for enslaved people in the eighteenth century, too. At least 500,000 enslaved Africans died from overwork and exploitation in French Saint-Domingue before the revolution even began. The nearly 900,000 captive Africans forcibly transported to the French side of the island lived an average of only three years afterward, while the life expectancy for those born in the colony was only fifteen years. Shakespeare’s Ferdinand could easily have been speaking of Saint-Domingue when he cried out in The Tempest—a play long considered to have been inspired by European colonialism in the Caribbean—“Hell is empty. And all the devils are here.”

The opposite belief—that it was the formerly enslaved of Saint-Domingue who were ruthless killers—is only partially a result of Dessalines’ postrevolutionary mandate authorizing expulsion or death for all white French people who chose to remain in independent Haiti. While that policy did result in the deaths of a few hundred white soldiers and colonists over the course of four months, it did not even come close to killing the entire French population, as the research of historian Julia Gaffield has shown.

Even though torturing and killing enslaved Black people was devastatingly common in the colony under slavery, constituting its own holocaust, and their deaths during the revolution inordinately outnumber those of white planters and French soldiers, numerous images imply precisely the opposite: Dessalines holding up a white man’s head, a nameless Black revolutionary doing the same. Divorced from historical context, such drawings hardly convey that what compelled the revolutionaries to borrow this classic tactic of terror was actually the deadly display of force relentlessly used by the French. In February 1791 the French government in Saint-Domingue notoriously had the heads of two revolutionary free men of color, Vincent Ogé and Jean-Baptiste Chavannes, placed on pikes to serve as a warning for anyone else who might try to obtain rights equal to those of the white colonists.

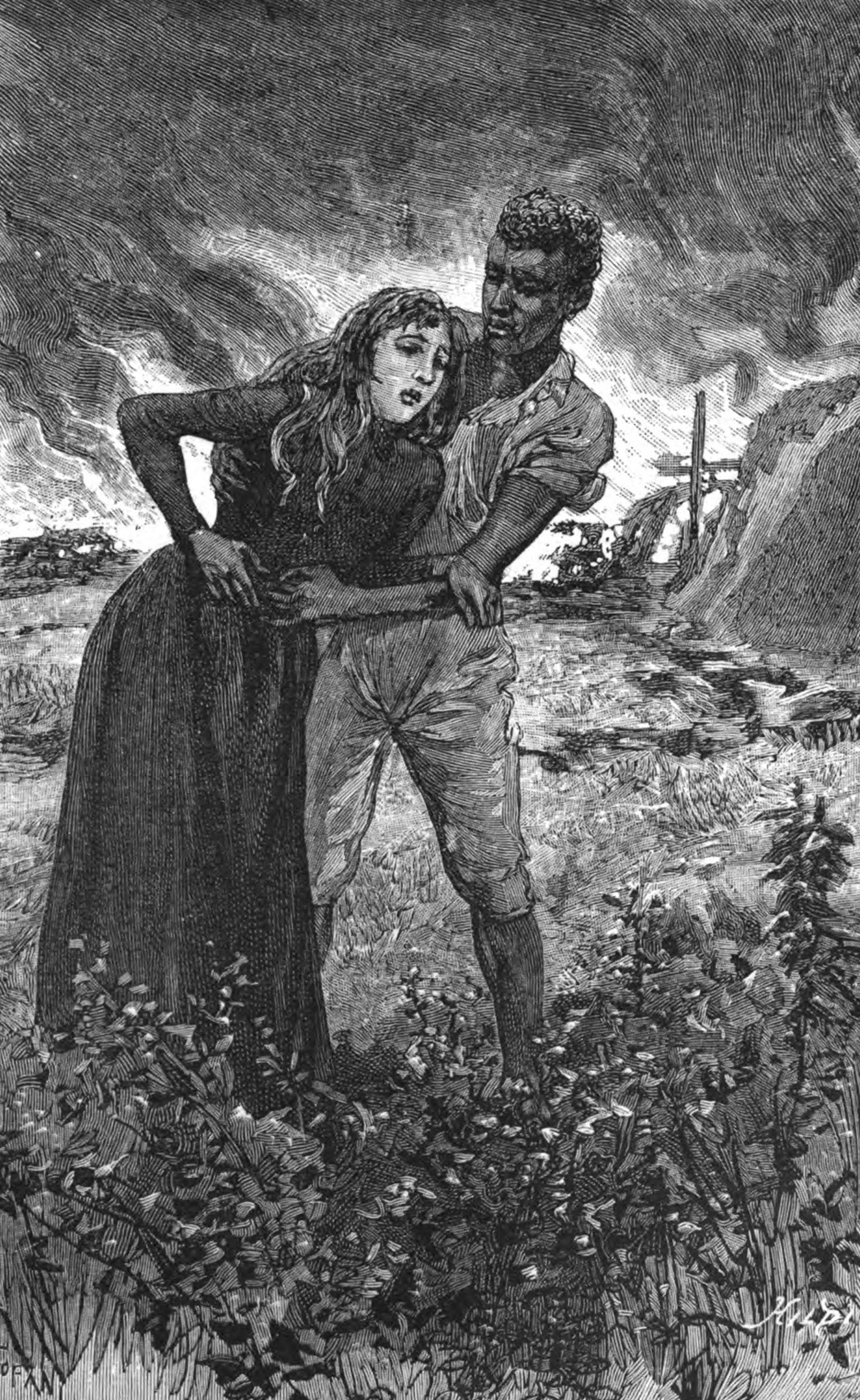

One rare sketch illustrating the preponderance of dead Black people over dead white people during the revolution comes from an 1888 children’s book, Armand Fresneau’s Thérèse à Saint-Domingue. Telling the tale of the white de Monrémy family’s flight from the slave insurrection that left their plantation in flames, the caption under one image reads: “The French guard was tasked with gathering the dead bodies.” Notably, these corpses are Black, not white. Yet when the book appeared in English translation the next year, this image was omitted. An engraving depicting the novel’s white title character in distress as she flees the revolution was preserved, however.

Another children’s story from the late nineteenth century contains an image expressing what may have been unwitting sympathy for the Black people of Saint-Domingue. This engraving of two children named Mika and Dodo weeping over the prerevolutionary death of Mika’s mother is from Michel Möring’s 1860 tale L’Esclave de Saint-Domingue (The slave of Saint-Domingue).

The story does not ultimately defend the Haitian Revolution, and Möring keeps the details of slave rebellion in the background, preferring to highlight the goodness of the tale’s principal characters instead. By making Mika and Dodo the saviors of a French family, the narrative implies that Black people are worthy of sympathy in the context of revolution only if they show benevolence and devotion to white people, even those who had once enslaved them.

We must look to contemporary artists to find deliberate attempts to represent not only the sadness, sense of loss, and everyday griefs of enslaved Black people in Saint-Domingue but also the utter fear they experienced during the revolution. Kimathi Donkor’s 2004 painting Bacchus and Ariadne refocuses the gaze on white violence, while also underscoring the sheer terror felt by Black people in Saint-Domingue. Its depiction of a Black woman silently gasping in horror as she witnesses the murderous rage of a white French soldier trying to bayonet a Black child is a dramatic departure from the almost monolithic nineteenth-century portrayals of Haitian revolutionaries assaulting white women and children.

Most contemporary Haitian artists who have painted the revolution have focused on more heroic and celebratory landscapes. In 1995 Madsen Mompremier unveiled the iconic Dessalines Ripping the White from the Flag, and André Normil’s Cérémonie du Bois-Caïman (1990) is undoubtedly the most famous depiction of the August 1791 ceremony that heralded the start of the Haitian Revolution.

Acknowledging that there existed great suffering in Saint-Domingue alongside great heroism is essential but rare. This is what makes the monument to the Heroes of Vertières so extraordinary. Named after the famous battle that ended the revolution, it depicts the fallen men and women who fought alongside those who lived to see Haiti become free. The steep price of Haiti’s independence is wrought in seven bronze figures.

It is hard not to see parallels with historical efforts to misrepresent the Haitian Revolution in our current moment, when protests against police killings of Black men and women in the United States are being portrayed by many in the American media as perpetuating violence rather than opposing it. If the statues at the Heroes Monument could speak, perhaps they might answer such mischaracterizations with the sorrows of slavery. The earnest expressions on the faces of the standing figures as they eternally sit with the dead—eyes upturned to the sky, seeming to plead for sympathy more than recognition—provide a stinging reminder that the enslaved did not kill like maniacs. Their enslavers did.