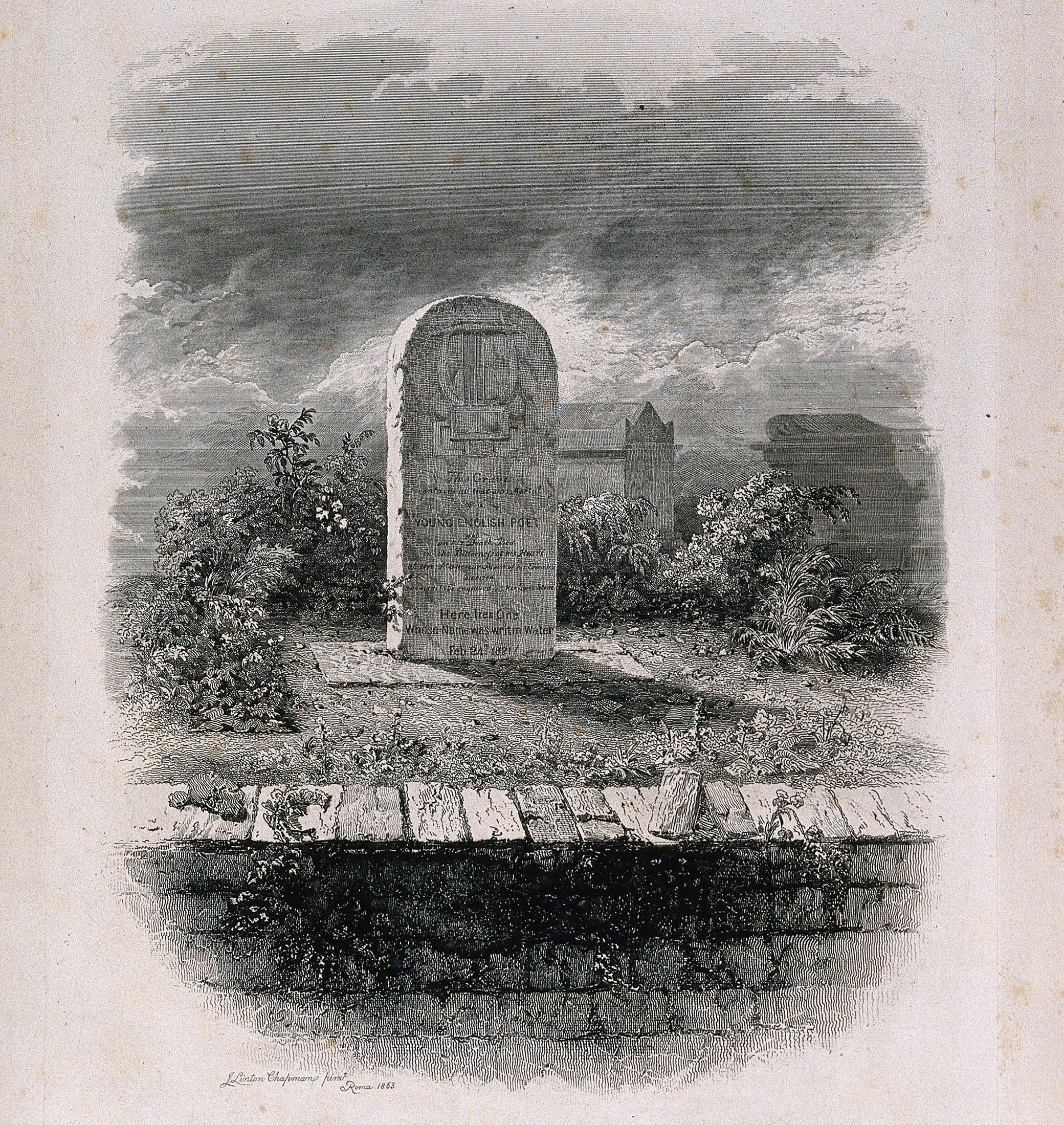

The grave of John Keats in the Protestant cemetery of Rome, by J.L. Chapman, 1863. Wellcome Collection.

Beautiful as it is to be buried where you were born, there’s something distinctively human about being buried where a journey took you. All cemeteries have the power to stir us to philosophy, but it’s that air of questing that makes Rome’s Protestant Cemetery the most moving graveyard I’ve ever visited. Writer Eleanor Clark said of the place, “This quiet garden keeps the dignity of human grief…It would be hard to find a [visitor to it] so stupefied as to come away without a mellower sense of life.”

The more accurate term for the Protestant Cemetery is the Non-Catholic Cemetery (Cimitero acattolico): there are Muslims, Jews, Marxists, and classicists buried there too. But I’m fond of the older term “Protestant Cemetery” because it carries in its semantics the protest of humanity against the strictures and corruptions it’s born into—a protest repeatedly expressed in the graveyard’s epitaphs, from triumphant declarations over accidents of birth like Horace Belshaw’s scholar educator and international servant who left his new zealand home to befriend the rural peoples of all nations to heartbroken sighs like John Keats’ “This grave contains all that was Mortal of a Young English Poet Who on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his Heart at the Malicious Power of his Enemies Desired these Words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone: Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water.” It’s a gathering of souls who, for better and worse, sought out a good life and met death on an odyssey— or, to use a more accurate term, an “aeneid,” for Odysseus’ journey brings him back to where he started, whereas Aeneas, the Trojan hero and begetter of what becomes Rome, dies on his destined journey, far from the home destroyed by Odysseus’ ruse.

Let’s have a look at my favorite epitaph in the Protestant Cemetery—by an English mother for her teenage daughter.

Beneath this stone are interred the remains of Rosa Bathurst, who was accidentally drowned in the Tiber on the 14th of March, 1824, whilst on a riding party, owing to the swollen state of the river, and her spirited horse taking fright. She was the daughter of Benjamin Bathurst whose disappearance when on a special mission to Vienna some years since, was as tragical as unaccountable: no positive account of his death ever having been received by his distracted wife. He was lost at twenty-six years of age. His daughter who inherited her father’s perfections, both personal and mental, had completed her sixteenth year when she perished by as disastrous a fate. Reader, whoever thou art, who may pause to peruse this tale of sorrows, let this awful lesson of the instability of human happiness sink deep in thy mind. If thou art young and lovely, build not thereon, for she who sleeps in death under thy feet, was the loveliest flower ever cropt in its bloom. She was everything that the fondest heart could desire or the eye covet, the joy and hope of her widowed mother, who erects this poor memorial of her irreparable loss. Early, bright, transient, chaste as morning dew, she sparkled, was exhaled, and went to heaven.

How much life—life in the beauty-adventure-tragedy-mystery-grief-love-death sense of the word—brims over in that single paragraph!

Having made a point of regularly visiting the tombstone in its breezy setting of pines and cypresses ever since first discovering it, I’ve yet to read it without choking up.

Rosa, the middle of three children born to Benjamin and Phillida Bathurst, was staying in Rome with her aunt and uncle, Lord and Lady Aylmer. Another of Rosa’s aunts, Tryphena Bathurst (later Thistlethwayte), who heard the story directly from Lady Aylmer, writes a letter about Rosa and the Aylmers on the tragic horseback ride. If we add to Tryphena’s letter an account by Mrs. Hugh Fraser, a diplomat’s wife and chronicler of Rome’s gossipy stories, who got the goods from Rosa’s sister in her old age, we can piece together what likely happened.

The Duc de Montmorency, the French ambassador and family friend to the Bathursts, asked his servant to lend his horse to Lord Aylmer. The riding party agreed, fatefully, to meet up with the Duc’s man, once he’d secured another horse, at the Ponte Milvio. “How often it is that the smallest causes produce the most signal results,” Mrs. Hugh Fraser observes. On that sunny spring day the Tiber was roaring with the meltwater of the heavy winter snows in the Apennines. Taking a shortcut to their meeting point, the party found themselves on a narrow path between a vineyard and the river. Rosa’s horse spooked and immediately slid into the swift waters. She cried out, “Save me, Uncle!” Lord Aylmer made two valiant efforts to rescue his niece and nearly drowned in the process. In the aftermath, a sizable reward was offered to anyone who could find the body swallowed by the Tiber—to no avail. “I can dwell no more on this fatal event,” Tryphena abruptly ends her letter, “Kind love to Henry and the children.”

Some of the pathos of the epitaph’s language derives from the power of the unsaid. Benjamin Bathurst, Rosa’s father, could have a riveting costume drama / spy movie made about him. He was sent in secret to Vienna with the purpose of persuading Emperor Francis I to join England in its war against Napoleon. With his “perfections” of character, Benjamin won over the Viennese. His success led to tragic results: the Battle of Wagram, a costly but decisive victory for Napoleon and the triumphal entry of France into Austria. Benjamin followed the Viennese court to Hungary where he met up with Metternich to encourage Emperor Francis I not to surrender. This time his perfections were insufficient. The Treaty of Schönbrunn was signed on October 9, 1809. Benjamin Bathurst is now atop Napoleon’s hit list. After agonizing how to get back to England, he decides to go through Germany, traveling by night. His letters home bristle with suspicion of strangers and friends, all of whom are would-be assassins. The next piece of evidence we have of his fate is discovered by two old peasant women on a road by the woods near Magdeburg: some of his clothes ripped with bullet holes and soaked in blood, in the pants pocket a letter to his wife begging her not to take another husband if he should die. The hastily penciled note also warns of a French spy, the Comte d’Entraigues.

At this point in our drama, we pick up the story of the epitaph’s author Phillida Bathurst. She writes a letter to Napoleon asking for permission to travel on the Continent in search of her husband but decides against sending it, fearing the emperor’s refusal.

Instead, under her maiden name, she strikes off with her brother for Berlin to talk directly to the powerful ambassador there. When they arrive, they’re shocked to find that the ambassador already has passports for them issued by Napoleon himself. “How,” she gasps, “can His Majesty have possibly known that we were coming to Berlin, for I have told nobody of my change in plans but my brother here?” “It is peculiar, isn’t it?” the ambassador says with an insinuating smile, “but there it is.”

They make use of the passports to travel around Germany for clues. They find the bloody clothes and the foreboding note. She hears a rumor that a well-known Saxon lady, shortly after Benjamin’s disappearance, was dancing at a ball with the governor of Magdeburg when he let slip, “All this fuss about this English ambassador, but what if I told you I had him under lock and key in my castle?” So Phillida heads straight to Magdeburg and harangues the governor for two hours straight, “entreating, threatening, calling down the Divine Anger upon him for his concealment of the facts.”

He assures her that, though he did have an English spy locked in his castle, it wasn’t her husband. In fact, he claims, the man in question, Louis Fritz, has now gone off with his wife to Spain. Fed up, Phillida goes to Paris to confront Napoleon himself, who assures her on his honor that he knows nothing of her husband’s fate. The heartbroken sleuth returns to London—and to three young children who had been left in the care of family and servants. A card is mysteriously brought to her from the Comte d’Entraigues, a name she recalls with a shudder from her husband’s letter. She arranges a meeting with the French spy at which he tells her that her husband is dead. Excusing Napoleon of any knowledge of what happened, he claims that Benjamin Bathurst, after having been kidnapped, had indeed been locked in the governor of Magdeburg’s castle and was eventually executed under orders of Fouche, a French official. If all that’s not enough for a movie, the Comte d’Entraigues and his wife are then both found murdered in their carriage one day after the meeting. According to subsequent newspaper reports, not only was the Comte d’Entraigues a French spy, but Madame d’Entraigues was a double agent, on the payroll of both the British and the French! A shred of evidence supports the spy’s story: no Louis Fritz was ever registered in the secret service department of the British Foreign Office. Plus, it does seem like the governor of Magdeburg was lying. But the fact is that we, like Phillida, are still in search of the truth about her husband, which is as “tragical” and “unaccountable” as life itself.

As for Rosa, known as “the angel girl,” she was the toast of Rome, especially among the sizable British population there. Just a decade younger than John Keats, who died three years before her in his apartment on the Spanish Steps, she was an embodiment of Keatsian Romanticism: endowed with adventurousness by her father, raised to be original and free by a self-possessed mother, and scarred by tragedies throughout her brief, intense life. Her charms inspired admirers to poetry, including Walter Savage Landor, who, according to an old copy of Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, “has made his moan over [Rosa’s] tragedy in more than one tear-spotted page of verse.”

The epitaph’s language trembles not only with Rosa’s vibrancy but with her mother’s anguish. A German forest had swallowed up Benjamin. Now an Italian river had swallowed up Rosa. In the rawness of her grief, Phillida didn’t even have the consolation of bodies to bury. Seven months after her drowning, in late October, one of Rosa’s admirers, Charles Mills, was strolling across the Ponte Milvio. The sun was setting, and he seized the moment to wander down by the banks and bask in the loss of the angel girl. There he saw two peasants poking at something in the shallow water: a piece of fabric exactly the blue of Rosa’s riding-habit. He ordered them to get shovels, and together they dug up the body. Thus it came about that her mother could erect a tombstone in the Protestant Cemetery over the remains of her daughter.

The story of Rosa’s disappearance into and reemergence from the Tiber makes the epitaph’s last sentence particularly arresting: “Early, bright, transient, chaste as morning dew, she sparkled, was exhaled, and went to heaven.” Her mother’s language distills from water’s savage indifference its tender loveliness: Rosa was like morning dew. The screaming, drowning, and coughing-up of a teenager are verbally transformed into the sparkling, exhaling, and evaporating of her soul. You can see why this epitaph was the favorite of the master wordsmith Henry James, who puts his finger on its unusual power: “an old-fashioned gentility that makes its frankness tragic.”

As juicy as the story behind the epitaph is, the greater mystery is philosophical in nature. “Reader, whoever thou art, who may pause to peruse this tale of sorrows, let this awful lesson of the instability of human happiness sink deep in thy mind. If thou art young and lovely, build not thereon, for she who sleeps in death under thy feet, was the loveliest flower ever cropt in its bloom.” Build not thereon. After the rest of the epitaph has conjured an alluring drama of escapades and splendor, three words cancel it all and open a huge emptiness. Build not on youth and beauty. Build not on earthly existence. It’s all too disastrously unstable. Build not your life on—life! But like so much of the spirituality in Rome, this rich memorial seduces with what it shuns: the loveliness of an intelligent young woman on her horse, the high-spirited riding party among the fragrant flowers, the intrigues of the mission on the Continent, the implied romance between the dashing Benjamin and the fierce Phillida, the inner life of the grieving mother, the quest to the Eternal City. “Build not thereon”—it’s as much a cry of anguish as a piece of advice.

It’s hard to read the epitaphs of any cemetery and not start wondering what your own life could be worth. The Rosa Bathurst tomb is a profound sermon, but instead of pushing a moral it poses a question. How should we live? Whereon should we build? So much of Rome is noisy hustle-bustle, but the Protestant Cemetery is quiet enough for this question to register. Cypresses and violets are interspersed among monuments that whisper not only in Latin, Italian, and English, but in German, French, Czech, Lithuanian, Bulgarian, Slavonic, Japanese, Russian, Greek. Towering in the background of the angel girl’s grave is the Pyramid of Cestius, a tomb built for a Roman official sometime between 18 and 12 bc, during a fad for Egyptian monuments. Percy Bysshe Shelley once wrote of the cemetery’s beauty, “It might make one in love with death, to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place.” It’s hard not to feel here what the ancients meant by “mortality”—namely, that we have such unique lives that when our bodies give out something priceless disappears forever. We don’t just perish—to be replaced by those who come after us. We die. You and I echo, but we don’t repeat. There will never be another Cestius, John Keats, Rosa Bathurst, or anyone else here, or anyone else anywhere. The journey is all about becoming who—as opposed to what—we are.

Just a few graves away from Rosa Bathurst’s is Shelley’s, with an epitaph from Shakespeare: “Nothing of him that doth fade / But doth suffer a sea-change / Into something rich and strange.”

Reprinted with permission from Rome as a Guide to the Good Life: A Philosophical Grand Tour by Scott Samuelson, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2023 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.