The Distrest Poet, by William Hogarth, 1737. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1932.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Emily Ogden, author of Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism, out now from the University of Chicago Press.

Edgar Allan Poe called it the best American satire ever written, but he admitted that Laughton Osborn’s Vision of Rubeta (1838) was “very censurably indecent—filthy is, perhaps, the more appropriate term.” With this mock epic, Osborn avenged himself on editor William Leete Stone, who had panned Osborn’s novel, The Confessions of a Poet, by Himself. The Vision recounts the career of the Manhattan demigod Rubeta, a thinly veiled version of Stone. Born upstate to the divinities Dulness and Levity, Rubeta sees his first newspaper while on a steamboat to the city. The thrill he feels at its “wholesale falsehood” and “obscene abuse” alerts him to his calling: he will become an editor.

Taking the helm of the New York Commercial Advertiser, Rubeta defends an abbess who has been accused—accurately—of pimping out her novitiates. (In reality, Stone had defended a Montreal convent against false prostitution charges.) “’Tis he!” the abbess exclaims when she first sees Rubeta, “the ass foretold me in my dream!” “Be bold,” she urges her champion, “I see, now, now, thy triumph nigh! / I see my ass spirt fountains to the sky!” The fountains the ass spirts are presumably the lies Rubeta will print in order to vindicate the abbess. That is not the only possible reading.

Osborn spent the better part of 1837 rhyming his couplets and nursing his grudge. Then in the fall, a gift from the universe: Stone made an ass of himself for real. Stone went to investigate mesmeric clairvoyant Loraina Brackett, who claimed to practice spirit travel, with the intention of debunking a hoax. He converted to her cause instead. That change of heart would dent Stone’s reputation and round off Osborn’s poem. Osborn threw together a final canto about Rubeta's love affair with the sibylline Loraina, and into print went the Vision.

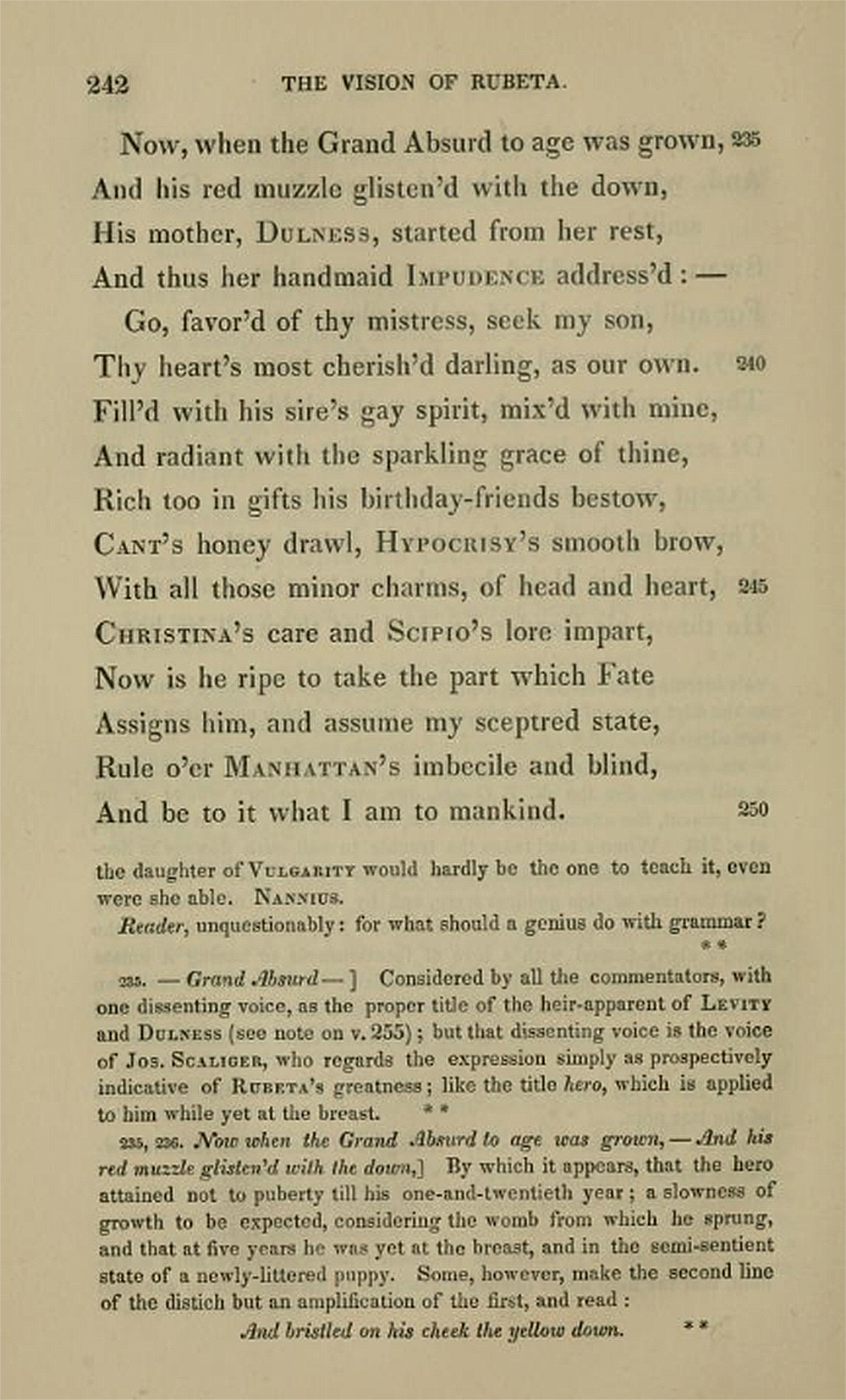

In the verses below from Canto IV, Dulness prepares to send her son Rubeta (the “Grand Absurd”) to Manhattan. The footnotes, part of Osborn’s faux-editorial apparatus, conjure an imaginary world of scholarly squabbling.

Now, when the Grand Absurd* to age was grown,

And his red muzzle glisten’d with the down,**

His mother, Dulness, started from her rest,

And thus her handmaid Impudence address’d:—

Go, favor’d of thy mistress, seek my son,

Thy heart’s most cherish’d darling, as our own.

Fill’d with his sire’s gay spirit, mix’d with mine,

And radiant with the sparkling grace of thine,

Rich too in gifts his birthday-friends bestow,

Cant’s honey drawl, Hypocrisy’s smooth brow,

With all those minor charms, of head and heart,

Christina’s care and Scipio’s lore impart,

Now is he ripe to take the part which Fate

Assigns him, and assume my sceptred state,

Rule o’er Manhattan’s imbecile and blind,

And be to it what I am to mankind.

* Grand Absurd: Considered by all the commentators, with one dissenting voice, as the proper title of the heir-apparent of Levity and Dulness; but that dissenting voice is the voice of Jos. Scaliger, who regards the expression simply as prospectively indicative of Rubeta’s greatness; like the title hero, which is applied to him while yet at the breast. ↩

** Now when the Grand Absurd to age was grown, / And his red muzzle glisten’d with the down: By which it appears, that the hero attained not to puberty till his one-and-twentieth year; a slowness of growth to be expected, considering the womb from which he sprung, and that at five years he was yet at the breast, and in the semi-sentient state of a newly-littered puppy. Some, however, make the second line of the distich but an amplification of the first, and read: And bristled on his cheek the yellow down. ↩

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Jeff Biggers, author of Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Alastair Bonnett, author of Beyond the Map: Unruly Enclaves, Ghostly Places, Emerging Lands and Our Search for New Utopias

• Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing