A train delivers military equipment to the border. Photograph by Robert Runyon. The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Monica Muñoz Martinez, author of The Injustice Never Leaves You, now available from Harvard University Press.

In the early 1900s bridges over the Rio Grande connected families and friends living in U.S. towns, like Brownsville, with families and friends living in Mexican towns, like Matamoros. People living in border towns moved back and forth across the river for work, for school, and for social gatherings. Border communities were interwoven, connected socially, culturally, economically, and by the life source of the river. When the railroad arrived at Brownsville in 1904, a new wave of Anglo migration brought a new racial order to the border region. Anglo farms quickly supplanted Mexican owned ranches. Jim Crow laws segregated ethnic Mexicans in schools, churches, and residence from Anglo newcomers. American citizens of Mexican descent were disenfranchised. In addition to being kept from voting booths, these citizens were prevented from serving on juries.

New Anglo residents also called for more policing on the U.S.-Mexico border. Ethnic Mexicans were cast as a racial threat to the safety of white Americans, to American capitalism, and to the nation more broadly. Calls to militarize the border were heightened when conflicts spurred by the civil war in Mexico reached northern Mexican towns abutting the United States in 1914. The United States responded by sending 100,000 troops to patrol the southern border.

Photographs of the border and of U.S. soldiers training with the newest military technologies were important for U.S. nation building. These images circulated in newspapers and convinced a broader American public that the U.S. military was prepared to join the global theaters of war in World War I—and that the government was capable of securing the southern border. While the United States was not at war with Mexico, U.S. soldiers trained their sights on the border and on border residents.

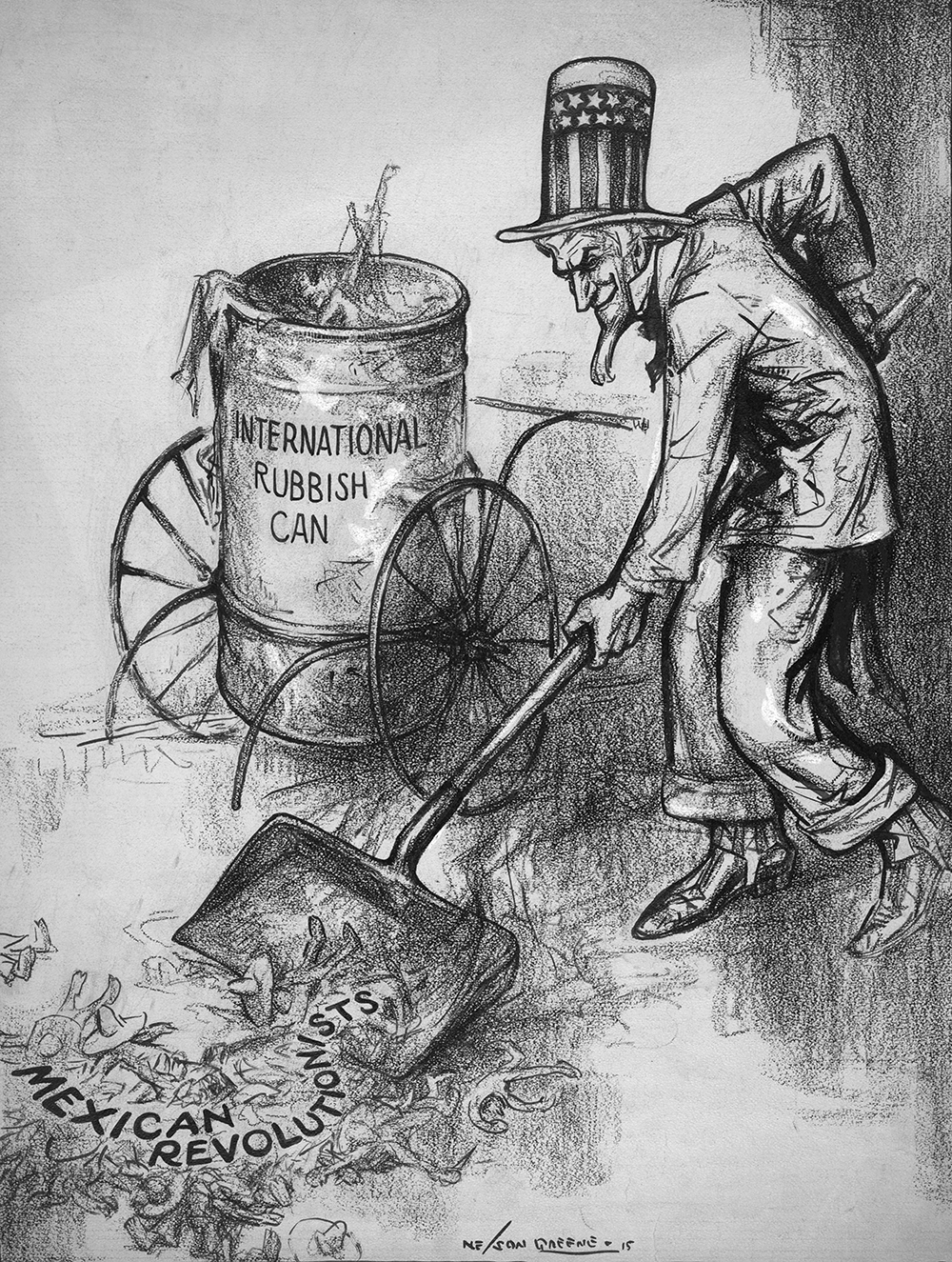

The press helped consolidate a national common identity in opposition to both the foreigners of neighboring Mexico and ethnic Mexicans living in the United States. The figure of the menacing Mexican bandit was cemented in popular American imagination in this era. The New York Evening Telegram published a cartoon by Nelson Green in 1915 that depicted Uncle Sam shoveling a pile of dead Mexican revolutionaries, wearing sombreros, into an “international rubbish can.” The cartoon did not portray the anonymous dead as victims of war or conflict. The grinning Uncle Sam looks satisfied with his work clearing piles of dead Mexican bodies.

In April 1916 an English-language newspaper, the Laredo Times, published a photograph of a U.S. cavalryman walking in front of three men—identified as “strange Mexicans” who stood in a line—holding their hats, their gaze turned down to the ground. The caption reads, “The photograph shows strange Mexicans being questioned by military authorities of the United States on the border. The men were liberated. Two of them later were found shot.” Their deaths by unidentified assailants, it seems, did not inspire a formal investigation. The newspaper never printed their names and made no further reference to the incident. The caption aimed to comfort readers by showing law enforcement agents actively patrolling both social and national borders. It also simultaneously worked to convince readers that a military presence on the border was necessary. When reading the title of the photograph, the role of who should perform this practice becomes unclear. The title could be read as a call to readers to join officials in monitoring the movement of “Border Mexicans.”

Dehumanizing representations of ethnic Mexicans had dire consequences. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the murder of ethnic Mexicans was common on the Texas–Mexico border. Historians estimate that between 1848 and 1928 in Texas alone, 232 ethnic Mexicans were lynched by mobs. These tabulations tell only part of the story.

Between 1910 and 1920, the decade of an expanded militarization of the border, ethnic Mexicans were harshly policed by an intersecting regime of vigilantes, state police, local police, and army soldiers. Historians estimate that hundreds of ethnic Mexicans died during this period. In death, the victims of racial violence were criminalized. Photographers labeled the dead with racial epithets like bandit and greaser. Customers bought the images as souvenirs.

Politicians called for the militarization and justified extralegal violence. During a Texas congressional investigation into abuse at the hands of the Texas Rangers in 1919, Congressman Claude Benton Hudspeth, representing the Sixteenth District of west Texas, stated,

A Ranger cannot wait until a Mexican bandit behind a rock on the other side shoots at him three or four times…You have got to kill those Mexicans when you find them, or they will kill you...I don’t believe in this, Mr. Chairman, in extending very much clemency to men who come across the River and murder our wives and children…Now I am going to be candid with you, talk about the mob law, if I had it in my power I would lead a mob in a minute against them, and if you reduce these Rangers or curtail them to the extent that they cannot cope with the situation and they continue to come across there and murder men and women like they did old Mickey Welsh and the little boy down at Glenn Springs and Glen Neville, there will be people that will respond, and I will come back from Washington to lead them if I am needed. We are going to protect our property.

Hudspeth endorsed a revenge-by-proxy form of policing. When it was reported that Mexican bandits raided an Anglo ranch, or worse, murdered an Anglo Texan, any ethnic Mexican in the region could be suspected and targeted with violence. Hudspeth helped to spread fear and enticed panic. He described hordes of Mexican bandits just south of the border, an ever-present threat, waiting for the right moment to attack. If the state reduced the agents, he believed, the consequences would be swift and violent. His account proved vital in convincing legislators from other regions of Texas that the criminal nature of Mexicans necessitated extralegal violence to maintain peace. To the congressman, any Mexican, on either side of the border, posed a dangerous threat. Hudspeth’s sweeping criminalization of an entire population sanctioned the use of violence as a strategy for policing the border region. In 1924, when Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924, the first comprehensive restrictive immigration law in the United States, Hudspeth pushed for a rider to the appropriations bill providing $1 million to establish a “land border patrol” to police the U.S. borders with Mexico and Canada.

This period of state sanctioned violence has largely been forgotten by Americans, due in large part to the work of the press, politicians, and later historians who represented racial violence as progress. Accumulating dead Mexican bodies on the border were presented to mean safer conditions for Anglo settlement, consumption, and capital. Current federal and state policing regimes have deep roots in the violence of the borderlands—the regime of terror practiced a century ago on the Texas-Mexico border is crucial to ongoing conversations about police brutality and the carceral state. The history reminds us of the dangers of criminalization and unchecked racial profiling and police abuse.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Tatjana Soli, author of The Removes

• John Wray, author of Godsend

• Imani Perry, author of Looking for Lorraine

• Ken Krimstein, author of The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth

• Katherine Benton-Cohen, historical adviser for the film Bisbee ’17

• Nicholas Smith, author of Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing