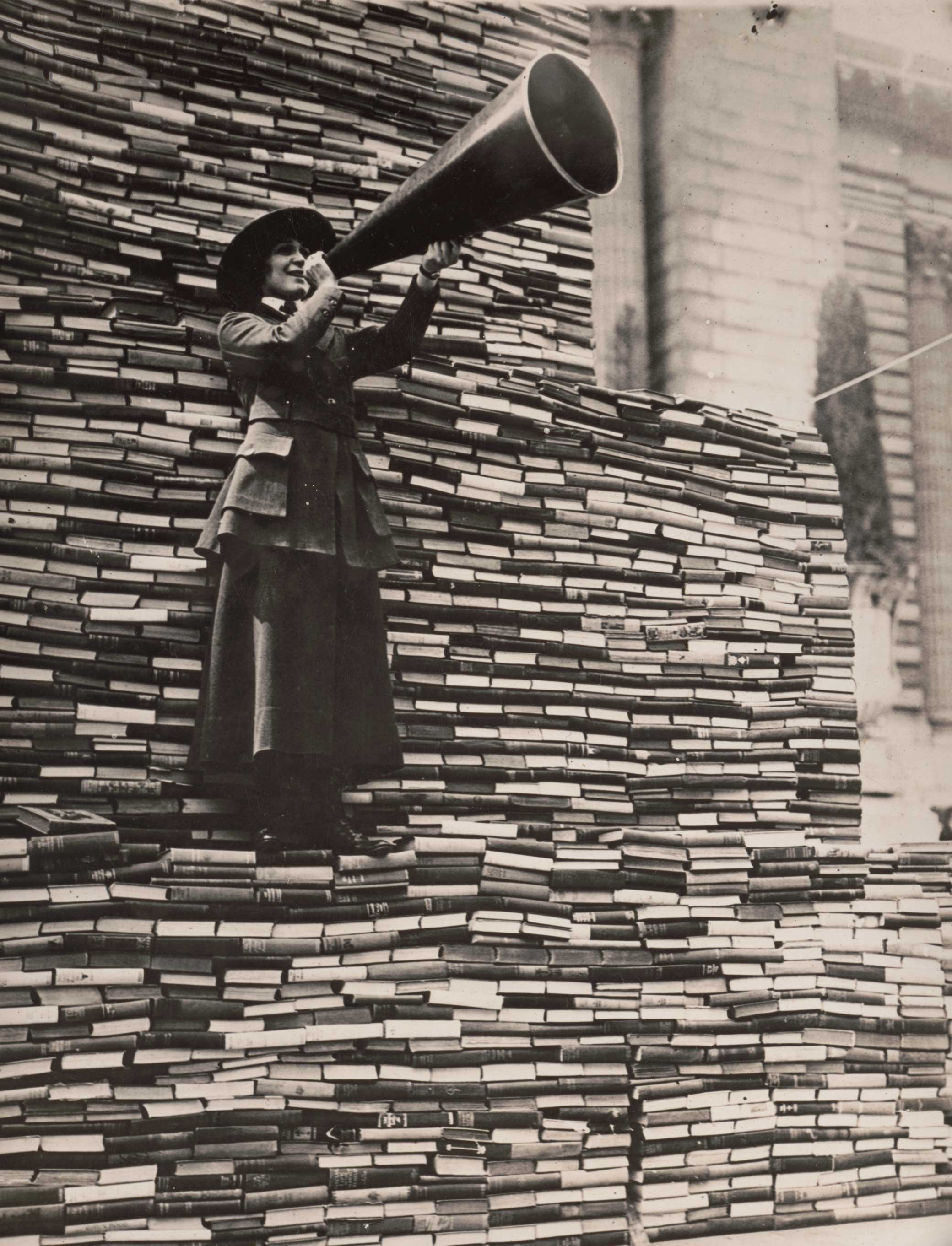

New York City book campaign, 1919. Photograph by Abel & Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In New York in the 1840s, books and printed matter were everywhere. Up and down Broadway, boxes of used books cluttered the sidewalks. Newsstands stocked papers, literary journals, and magazines, while street vendors hawked the latest serialized novels by Dickens: “He-e-ere’s the New World—Dick’s new work. Here’s the New World—buy Master Humphrey, sir?”

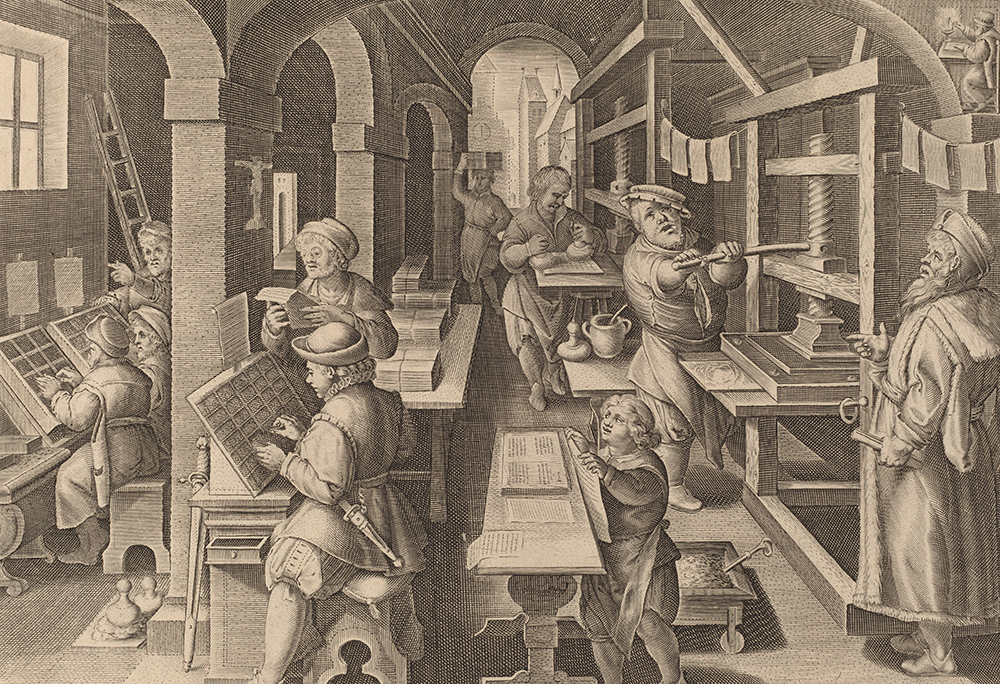

From storefront windows, new books appealed to pedestrians with siren songs of entertainment and instruction at bargain prices, while literary annuals, gift books, and illustrated editions catered to an expanding American readership. New steam-powered rotary printing technology invented in New York in the mid-1840s revolutionized the print industry, rolling out thousands of pages per hour, while other innovations, such as stereotype printing, enabled a boom in cheap reading matter. By 1851 publisher George Palmer Putnam had begun stocking bookstalls at railway depots with paperback “Railway Classics,” light and entertaining reading for busy persons in transit. Mass-produced paper, machine-made from wood pulp rather than handmade from cotton, also stimulated growing networks of transcontinental and transatlantic correspondence. “This vile thin paper is my abhorrence,” complained publisher Evert Duyckinck to his brother George. “It is characteristic of the age. Would Milton have written on it? The aqua fortis of his Eikonoclastes would have gone through a quire of it. Charles Lamb never could have used it.”

The sons of Evert Duyckinck Sr., one of the first bookseller-publishers in New York and by the time he retired the oldest, believed that criticism went hand in hand with authorship and that the advancement of literature depended on a longer literary tradition. “Time selects his favorites on different principles from modern booksellers,” the younger Evert Duyckinck wrote in 1848. “The latter affect plausibility and easy reading. Time keeps his books as he does his oak trees for their knotty strength. The company is a great deal better at these old tables than at the new ones. The shallow evils have been intoxicated long since and carried out; only the good heads and strong brains keep the ground.” The attitude can be traced back to the European Enlightenment, when critics and philosophers worked to forge a standard of literary taste based on a vernacular literary canon. Just as the ancient classics had emerged from the “Dark Ages” to take on new life in the form of early printed books, the modern classics, many believed, would emerge from a body of literature that had been well sifted.

By the nineteenth century, readers were feeling lost in a sea of print, and though this feeling was not entirely new, it was exacerbated by new print technologies and cheap reprints flooding the literary marketplace. “There is a literal deluge of moral and colorless works, from which even the average modern reader comes away only with an uncomfortable sense of waste of time and eyesight,” complained the bibliophile William Carew Hazlitt in his study of book collecting. Tweaking a phrase from Ecclesiastes (“of making many books there is no end”) that was frequently quoted in bibliographical writings, he spoke for many when he wrote, “Of printed matter in book-shape there is no end.” Literary essayists on both sides of the Atlantic—reviewers, journalists, men of letters—offered themselves as guides through this sea of print, and the Duyckinck brothers, Evert and George, in New York City were among them.

The Library of Choice Reading, a series of reprinted European books Evert edited for the publishers John Wiley and George Palmer Putnam, which included works by Charles Lamb and his fellow English essayists Leigh Hunt and William Hazlitt, recognized the principle of choice or discrimination as the key element of literary taste. In an advertising flyer announcing the Library of Choice Reading on March 1, 1845, Evert explained the logic for the series, claiming that the “so-called Cheap Literature, while it has failed to supply good and sound reading, and has been attended with many publishing defects, has in some degree prepared the way for the new demand. It has shown the extent of the reading public in the country and the policy of supplying that public with books at low prices.” The Library of Choice Reading was intended to meet that demand with reprints of well-chosen books, while its companion series, the Library of American Books, was designed to publish choice works by American authors—Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, John Greenleaf Whittier, Margaret Fuller (and, had Evert had his way, Ralph Waldo Emerson). Together these two book series constituted what the historian Ezra Greenspan has called “the central event in American literary publishing, the most ambitious attempt to date to circulate high-quality, contemporary works among the American reading public.”

While Evert copyrighted unpublished works by up-and-coming American authors for his Library of American Books, he worked out “Courtesy of the Trade” agreements, which served as de facto copyright contracts, with British publishers like Edward Moxon for his Library of Choice Reading. Despite the practices of many American publishers, both he and his brother believed in the importance of respecting intellectual copyright. At the Duyckinck family home at 20 Clinton Place (now Eighth Street from Sixth Avenue to the Bowery), Evert and his fellow literary essayist Cornelius Mathews (with whom Evert edited the journal Arcturus) held meetings of the “American Copyright Club.” As George put it (quoting Mathews), “if good copyrights are not to be had it is best not to begin.” In this respect they differed from other participants in what the literary historian Meredith McGill calls the American “Culture of Reprinting.” This period, as she defines it, lasted from 1834 to 1853.

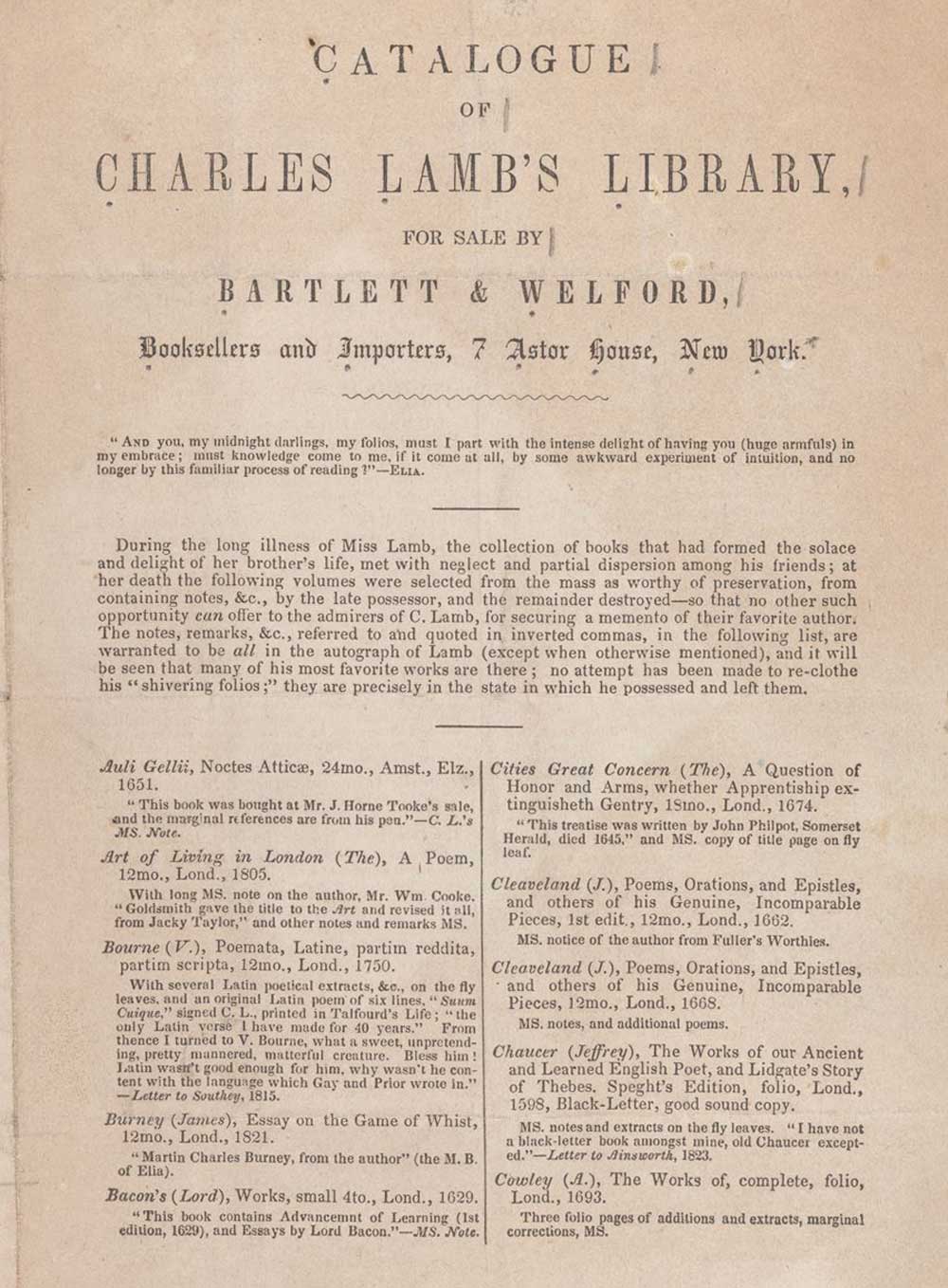

When Charles Lamb’s library went on sale in 1848, Evert did not feel the need to acquire any books. The Duyckinck family library already contained copies of most of the books from Lamb’s library, and Evert felt that obtaining duplicates just because they had once belonged to the essayist was contrary to the spirit of Elia—Lamb’s best-known essayistic persona. “It is acting much more in Lamb’s spirit to get books as he did from the stalls for the good matter within than to pay an extravagant price for his copies & thereby mutilate some of the justices and charities which he practiced,” he wrote to George in Paris, explaining that he let the “ ‘books’ go by to more wealthy or careless purchasers.”

By the time of Evert’s death, the Duyckinck family library would have grown to major bibliomaniacal proportions, with upwards of fifteen thousand volumes of English and American literature, a number few elite private libraries in America could boast, but one thing the association copies from Lamb’s library had that the same books from the Duyckinck family library did not have was the autograph marginalia by Lamb and his friends. “The least touch of Lamb’s fingers,” Evert observed, “a mere marking of the pencil or one illustrative parallel quotation seemed to carry with it other portions of his genius. Few words from him or Coleridge are as good as other men’s books.” With the permission of the clerks at the bookstore, he brought his own copies of the titles in Charles Lamb’s library to Bartlett & Welford’s and copied the marginalia Elia’s books contained. For the longer passages, he used notebooks.

Evert Duyckinck had been preoccupied with his Library of Choice Reading, but now, “baiting gloriously among the old authors,” he found that after the lapse of a half-dozen years since he had opened many of them, they again struck him as new. “You can hardly go amiss in anything bearing the date seventeenth century,” he advised George.

By the time attorney George Templeton Strong diagnosed his own bibliomania in 1842, the book madness had gripped New York. “Bibliomania is a kind of constitutional disease with me,” he confessed to his diary. “I’ve been subject to it almost as long as I can remember.” The auctioneers who later dispersed his library described his collecting habits as those of a discerning belletrist, “never confining himself to any particular branch of English literature, but purchasing with care and discrimination only books possessing genuine intrinsic value, remarkable historical importance, or some unique and interesting peculiarity.” He was finding his way to producing a library that was itself “exceedingly rare” and that in the category of association copies included nine volumes from Charles Lamb’s library.

Strong purchased all five books in Bartlett & Welford’s Catalogue of Charles Lamb’s Library with autograph writing by Coleridge, a man legendary as a conversationalist for whom Lamb’s books were silent interlocutors, receiving his generous commentary and preserving it for future generations. Elia describes such commentary as “in matter oftentimes, and almost in quantity not unfrequently, vying with the originals.” Coleridge’s most extensive marginalia in the association copies sold by Bartlett & Welford were contained between the covers of Lamb’s copy of Poems, &c. by John Donne Late Dean of St. Pauls. With Elegies on the Authors Death. To Which Is Added Divers Copies Under His Own Hand, Never Before Printed (1669). “How much is there of Coleridge’s mind for us to travel [in] and when we think we have accomplished the feat we shall be in a condition to begin the journey,” marveled Evert Duyckinck when he read those notes in the Astor House.

On the flyleaves and in the margins of Lamb’s copy of Donne, Coleridge left nothing less than a detailed theory of poetics, attempting to explain the idiosyncratic verse style of the metaphysical poet in terms other than conventional neoclassical verse meter. He claimed that “not one in a thousand of his Readers have any notion of how his Lines are to be read—to the many 5 out of 6 appear anti-metrical.” Understanding Donne’s accentual syllabic verse was not merely a matter of scanning lines and grouping syllables into poetic feet, as schoolboys learned to do with quantitative verse in Latin and Greek. A subjective element was involved. “To read Dryden, Pope &c., you need only count syllables,” Coleridge wrote, “but to read Donne you must measure Time, & discover the Time of Each word by the Sense & Passion.” Such a poetics involved the sensibility of the reader.

At once radical and conservative, Coleridge’s approach to Donne authorized the reader not only to supply the missing quantitative element of English verse by intuiting whether vowels (and hence syllables) should be long or short, but also to add, skip, or rearrange words in order to convey semantic or emotional content. “I am convinced that where no mode of rational Declamation, by pause, hurrying of voice, or apt, some times double, Emphasis can at once make the verse metrical & bring out the sense & passion more prominently, that there we are entitled to alter the Text, when it can be done by simple omission or addition of That, Which, And, & such ‘small Deer’—or by mere new-placing of the same Words.—I would venture nothing beyond.” The reader was justified in modifying minor but necessary features of language, such as pronouns, articles, and conjunctions, when it seemed right to do so. Coleridge compares such linguistic elements to “small Deer,” or the rodents that Edgar, disguised as “poor Tom” in Shakespeare’s King Lear, hunts for food: “Mice and Rats, and such small deer, / Have been Tom’s food for seven long year.” Gobbling up or spitting out such critters according to individual taste was the prerogative of the actively engaged reader.

On the back flyleaf of Donne’s Poems, he had written, “I shall die soon, my dear Charles Lamb! and then you—will not be vexed that I had bescribbled your Books.” Although Coleridge was nowhere near death at the time, he could not have known that. But he certainly did know that he was not spoiling Lamb’s book. “Spite of Appearances,” he wrote elsewhere in the volume, “this Copy is the better for the Mss. Notes. The Annotator himself says so.” Coleridge’s notes in Donne’s Poems were performative and, as at least one critic has noted, “reflect the imaginary presence of Lamb.”

Coleridge was in conversation not only with authors and owners of books but also with other readers. We see this in a copy of Thomas Browne’s Pseudodoxia Epidemica: or, Enquiries into Very Many Received Tenets, and Commonly Presumed Truths (1658), which Lamb presented to Coleridge at dinner on March 10, 1804. The book, whose Latin title means something like “widespread false teachings,” was an inspiration for Lamb’s “Popular Fallacies.” Coleridge exulted in the gift and read it the same day. At midnight, he sat down with it at his desk at Barnard’s Inn (an Inn of Chancery) and addressed a letter to Wordsworth’s sister-in-law Sara Hutchison, with whom he was hopelessly in love, on its front flyleaf. “My Dear Sara!” he began; “Sir Thomas Browne is among my first favorites.” To guide her reading, he provided a key to his annotations:

¥ a profound or at least solid and judicious observation

= majesty of conception or style

// sublimity

X brilliance or ingenuity

Q characteristic quaintness

F an error in fact or philosophy

Coleridge sent the book to Hutchison, who passed it on to Wordsworth, who signed its title page, “W. Wordsworth, Rydal Mount,” thus declaring proprietary status. The American rare book curator Gerald D. McDonald observed that “Wordsworth assaulted Lamb’s books as he did everyone’s.” He noted that Thomas De Quincey once saw the poet tear into a book with a butter knife, literally, to open its pages, leaving “its greasy honors behind it on every page.”

From Book Madness: A Story of Book Collectors in America by Denise Gigante, published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2022 by Denise Gigante. All rights reserved.