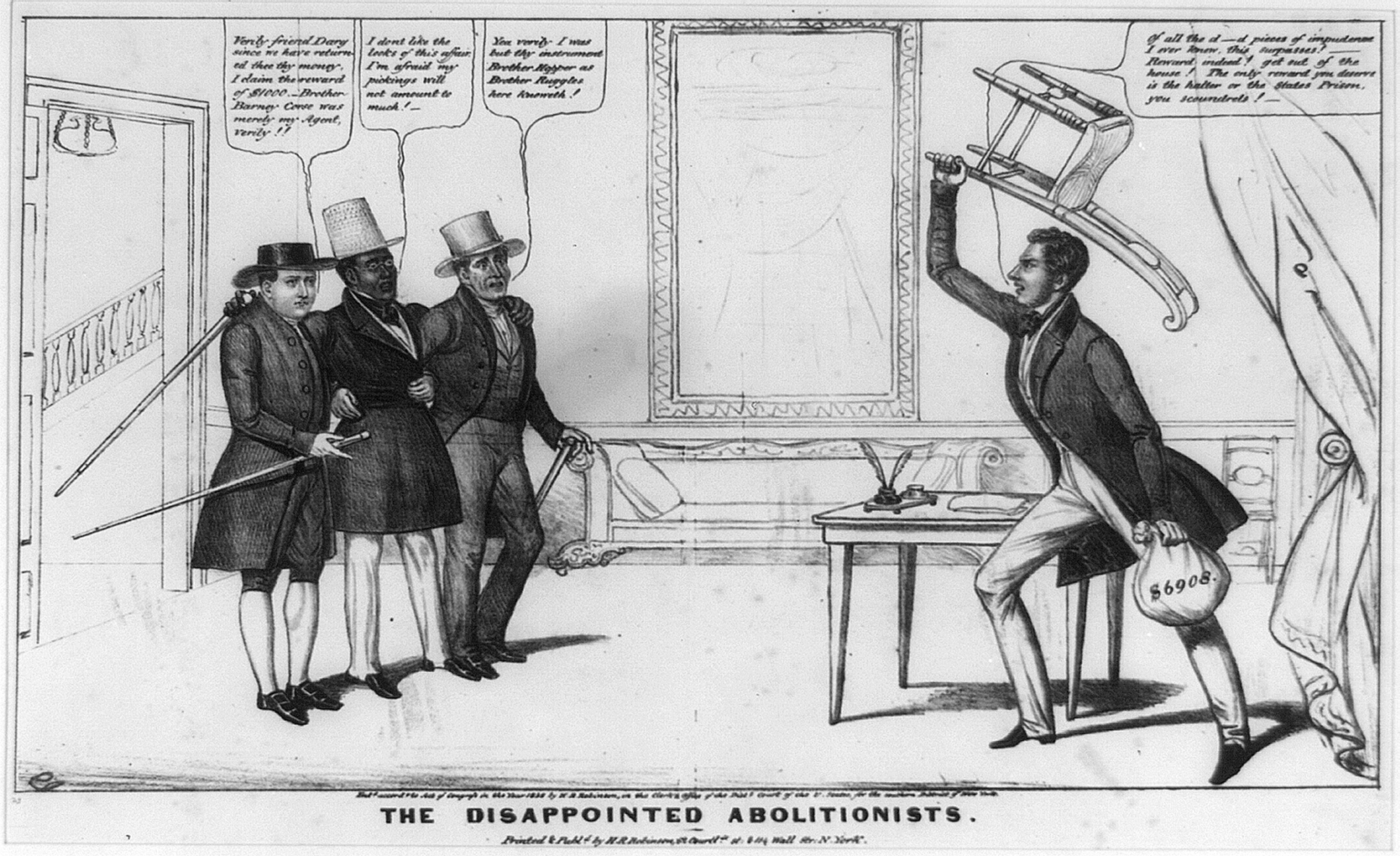

The Disappointed Abolitionists, by Edward Williams Clay, c. 1838. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

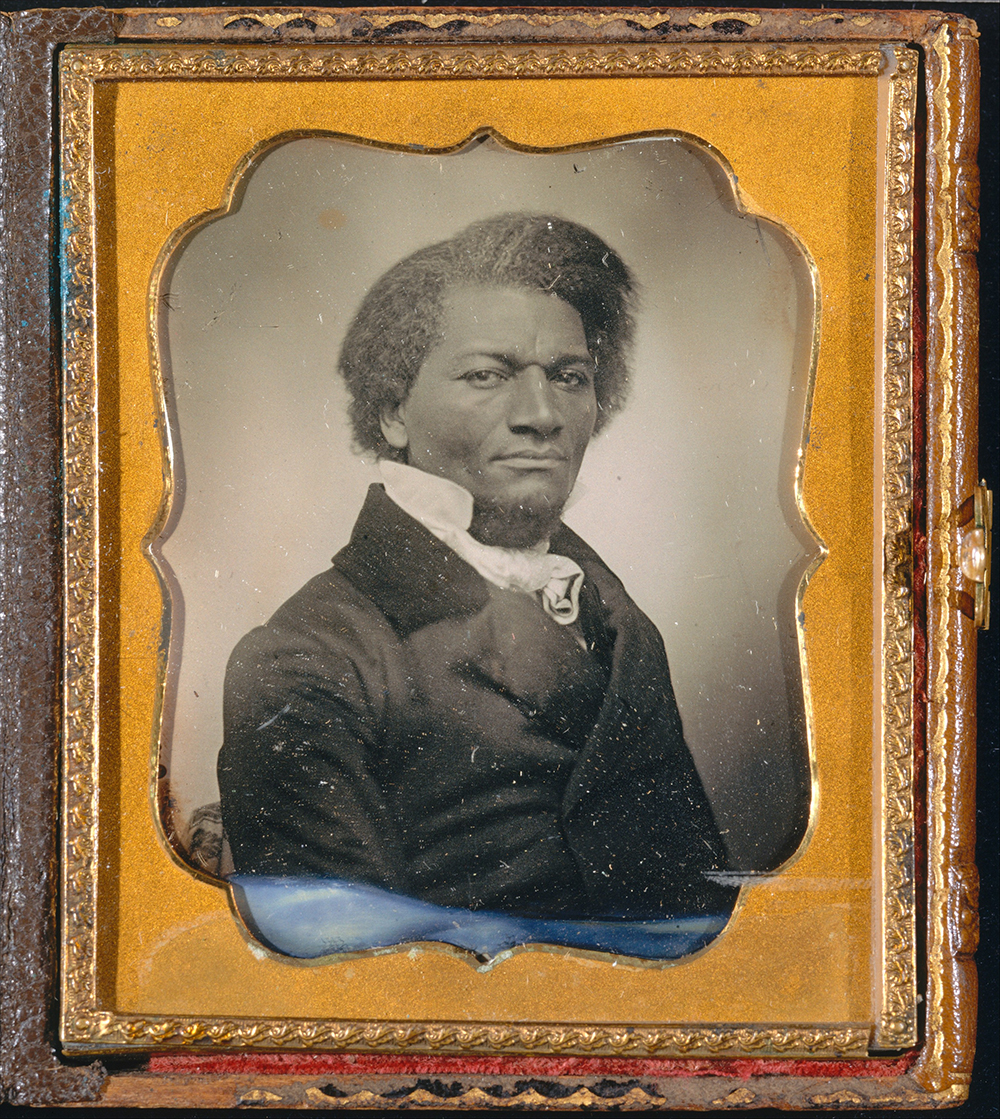

On September 4, 1838, Frederick Bailey, a twenty-year-old fugitive slave, stepped off a ferryboat onto Manhattan Island and began his first full day as a free man. New York City was a temporary waystation, a place where he could disappear into the crowd. He was filled with joy at the urban spectacle: “I was walking amid the hurrying throng,” he later recalled, “and gazing upon the dazzling wonders of Broadway. The dreams of my childhood and the purposes of my manhood were now fulfilled.”

Joy quickly turned to fear. By sheer luck, Bailey ran into someone he knew—another escapee, working as a whitewasher under a new name: William Dixon. Dixon warned Bailey that “the city was now full of Southerners” returning home from their annual summer vacations in the north and that “there were hired men on the lookout for fugitives from slavery,” including some black New Yorkers “who, for a few dollars, would betray me into the hands of the slave-catchers; that I must trust no man with my secret.” Bailey realized that he was “an easy prey to the kidnappers, if any should happen to be on my track.”

After spending a lonely night on a deserted wharf, Bailey made his way to the bookstore and home of David Ruggles, secretary of the New York Committee of Vigilance, an organization founded in 1835 to confront slavery and racism head-on. Born to free black parents in Connecticut in 1810, Ruggles had been a sailor, a grocer, and a printer before turning his home into a shop selling antislavery books and a meeting ground for the city’s black and white abolitionists. By 1837 Ruggles and his comrades had already helped more than 335 African Americans escaping slavery.

Years later, after Frederick Bailey had changed his name to Frederick Douglass and become the nation’s most prominent African American activist, he remembered his New York host with appreciation: “Mr. Ruggles was the first officer on the Underground Railroad with whom I met after reaching the north…He was a wholesouled man, fully imbued with a love of his afflicted and hunted people...”

By the time Bailey arrived on Ruggles’ doorstep, the bookstore owner and a small band of other New Yorkers had been fighting slavery and racial discrimination for nearly a decade. Although New York State’s remaining slaves had been freed in 1827, many white New Yorkers treated their free black neighbors with suspicion or open hostility. White artisans kept African American workers out of many of the city’s jobs and labor unions, while a growing population of Irish immigrants competed with black men and women for positions as servants, laundresses, seamstresses, waiters, barbers, and street vendors. Black children were limited to a small number of segregated schools. White business owners excluded “colored” people from equal treatment on the city’s streetcar and steamboat lines, most boardinghouses and hotels, and many restaurants. The New York Zoological Institute refused to admit black New Yorkers as customers. Nor did freedom bring political rights. New York State’s 1821 Constitution required black men to own at least $250 in property in order to vote, and very few black New Yorkers had enough money to qualify; black women, like white women, were barred from voting completely.

On top of all this, thousands of white New Yorkers were ardent defenders of Southern slavery. The city’s economy rested heavily on trade with the South: New York merchants and bankers shipped slave-grown cotton to England, extended loans to Southern planters so they could plant their crops and buy new slaves, and insured their property. New York retailers, wholesale dealers, and working people profited when Southern merchants and planters arrived in town to buy textiles and stay in Broadway hotels. Often those Southerners brought their enslaved servants with them, which New York State law allowed them to do for up to nine months at a time.

Most New York City voters, moreover, were members of the Democratic Party, which actively supported slavery. When antislavery activists tried to hold an interracial meeting in the Chatham Street Chapel in July 1834, white mobs started three days of riots, driving some five hundred African Americans out of their homes. In sum, New York often seemed to be as much a Southern city as a Northern one, a place whose economy and politics were bound up with slavery. No wonder that in 1839 the Colored American, the city’s black newspaper, blasted what it called “the deep and damning thralldom which grinds to the dust the colored inhabitants of New York.” Sixteen years later the black abolitionist William Wells Brown repeated the charge when he denounced “the pro-slavery, negro-hating city of New York.”

Facing such bleak circumstances, Ruggles and his colleagues dedicated themselves to bringing change through direct action. By the early 1830s Ruggles was a key member in a circle of activists based in the city’s black church congregations and in black self-help organizations like the New York African Society for Mutual Relief. He identified strongly with William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society, which called for interracial action to end American slavery immediately. But while Garrison advocated a course of nonviolence, Ruggles felt differently. He called for “practical abolition,” meaning that black and white abolitionists must confront slave owners and their allies forcefully, even in the streets of New York City. “Whatever necessity requires, let that remedy be applied,” he wrote in 1836. “Come what may, anything is better than slavery.”

Ruggles’ solution was the Committee of Vigilance: a group of black and white New York antislavery activists he helped create in Manhattan in 1835. The committee’s goal was to “protect unoffending, defenseless, and endangered persons of color, by securing their rights as far as practicable.” Ruggles was the committee’s secretary and lead actor, and New York, as the nation’s major seaport, gave him plenty of opportunities to put theory into practice. In December 1836, for example, after the Portuguese slave ship Brilliante arrived in the harbor with five enslaved Africans on board, several men connected to Ruggles sprang into action. On Christmas Eve they stormed the Brilliante and escaped with two enslaved men. When a sailor tried to stop them, “one of the gang cocked a pistol at him, and threatened to blow his brains out.”

The committee also used direct confrontation to fight for Southern slaves whose masters brought them to New York but openly ignored the nine-month limit. Enslaved servants, both men and women, fought to use the law to escape or argue for their own freedom. Ruggles and his allies confronted slave owners face-to-face to try to force emancipations; the meetings sometimes became shouting or shoving matches. In one case in 1838 an enraged Virginian, John P. Darg, had Ruggles thrown into jail after he tried to negotiate freedom for Thomas Hughes, a slave of Darg’s who had run away in New York with several thousand dollars of his master’s money. Despite the setback, the abolitionists eventually won Hughes’ freedom—after the master tried to sell him into the Deep South.

But most important to the committee was their crusade against the kidnappers who posed a threat to every black resident of New York City. Paid agents and bounty hunters roamed the city, seeking to capture runaways. They were aided by city officials who allowed black men, women, and children to be jailed and shipped south with few questions asked, even though state law supposedly required they be granted trial by jury. The city’s “kidnapping clubs,” as Ruggles called them, went even further: city officials pounced on legally free black New Yorkers and dragged them south for sale on the flimsy assertion that they were runaways. Children as young as nine-year-old John Welch, lured from his Mulberry Street home, were caught up in this dragnet and were sometimes shipped hundreds of miles away before their parents could plead for their return.

With funds provided by local white abolitionists and by a network of one hundred black New Yorkers who raised cash from hundreds more, the Committee of Vigilance hired skilled lawyers to help captives held in city jails or already deported to the South. Although the city’s judges—many of them well-connected Democrats— sometimes refused to cooperate, by 1838 Ruggles and his committee had saved a reported 522 individuals from slavery. The committee counted on the influence and support of its white members, but black men and women were its troops on the ground, keeping an eye on potential kidnappers and mobilizing the city’s African American community to assist Ruggles.

Ruggles also put together a network of safe houses and churches across the northeast that became stops on the “Underground Railroad” to freedom. By the 1840s, New York City’s Committee of Vigilance had inspired the creation of similar groups in Philadelphia, Albany, Boston, Rochester, Cleveland, Detroit, and elsewhere, all bent on helping African Americans to flee from and resist slavery.

The Committee of Vigilance was largely forgotten as historians in later decades focused on the efforts of white abolitionists or singled out just a few black antislavery activists such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman for attention. For most black New Yorkers and their white allies who struggled in later generations against racism, segregation, and discrimination in New York City as well as in the South, the name David Ruggles meant nothing. Yet in their efforts these later activists unknowingly echoed the defiance of the leader of the New York City Committee of Vigilance, who had once proclaimed, “I have tried to do my duty, and mean still to persevere, until the last fetter shall be broken, and the last sigh heard from the lips of a slave.”

Excerpted from Activist New York: A History of People, Protest, and Politics by Stephen H. Jaffe, published by New York University Press. Copyright © 2018 by Museum of the City of New York. Used by permission of New York University Press.

Activist New York is currently on view at the Museum of the City of New York.