Soap Bubbles (detail), by Thomas Couture, c. 1859. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Bequest of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, 1887.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

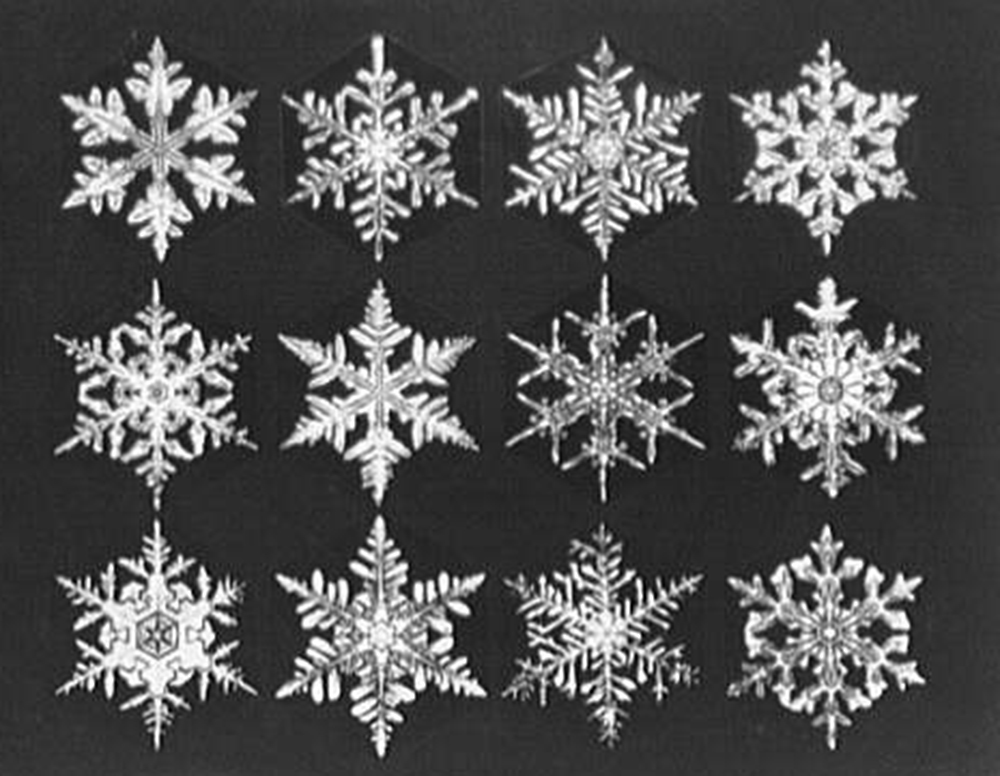

Etymologically, the writing of books; presently, the description or enumeration of books already written. As an appendage to academic scholarship, the bibliography can be said to offer a genealogy of an author’s intellectual resources. The (generally alphabetical) bibliography of a scholarly work amounts to a constellation of adjacent and coincident texts; it situates the work itself within a (putatively) emergent field of interlocutors, even as it also (generally) invokes a more or less pregiven disciplinary territory. It is nevertheless rare that one encounters identical bibliographies for different works. Bibliographies thus resemble snowflakes, insofar as they elaborate a “uniqueness” (a mastery of texts that is ultimately bound to an individual scholar) that is from any distance perfectly monotonous. Though commonly understood as a “thing,” bibliography also refers to the systematic description of books as material objects, sometimes, as in the case of cataloguing private collections, with attention to the correspondence between knowledge and its position in space. The architectural dimension of the bibliography reminds the reader that the text is not constituted as a stable knowledge object, but is in fact rearticulated by its user. Thus the bibliography may reveal an author’s omissions, secrets, and blind spots, no less than his/her considerable erudition; indeed, it may reveal that the work fails to produce knowledge over and against the texts in the bibliography itself. In this case, the truest bibliographer would be the librarian, who pledges to care for knowledge rather than make it.

HISTORY

A term of some ambiguity, meaning as it does both the past and the study of the past. This unfortunate conjunction has occasioned a good deal of confusion, historically. As a disciplinary formation within the modern landscape of research and teaching in institutions of postsecondary learning, history is sometimes classified with the social sciences and at other times with the humanities. This taxonomic ambivalence reflects multiple genealogies for the enterprise as a whole, which are themselves reflected in divergences of practice among professional historians: on the one hand, a preponderance of such practitioners understand their primary objects to be persons (their collective and individual experiences, conditions, and activities); on the other hand, a smaller but still significant community prefer to focus their energies on larger structures or dynamics (e.g., the state, the economy). The latter tend to do work that is more easily assimilable to the enterprises of economists and political scientists; the former tend to do work that feels more germane to students of literature and culture. That said, there is, in practice, a fair bit of overlap (and some back-and-forth) across these domains, and even those scholars working at the extreme antipodal verges of this distribution can recognize each other as historians. The explanation for this has less to do with a shared theory of historical knowledge as such, or a shared account of the proper object of historical inquiry, or even with a shared conception of the proper bibliography for training historians, and more to do, it would seem, with a pervasive and robustly conserved notion of what historical labor looks like. Which is to say, historians recognize what counts as the work of a historian. Essential to this shared formation: the archive. Broadly speaking, and with almost no exceptions, historians, to be historians, must spend some time recovering stuff about the past from collations of documentary source material that hails from the past period in question. The exceptions here (e.g., classical historians) tend to prove the rule, in that such marginal cases (historians of the classical period tend not to have access to archives, and must work from established texts) tend to be found with much reduced frequency within history departments themselves (a classical historian will be more likely found in a department of classics). The same dynamic can be identified among “ethnohistorians” and those historically concerned with nonliterate peoples: neither group is well represented in actual departments of history. When it comes to distribution requirements for undergraduates, a number of colleges and universities require some exposure to “Historical Analysis” or the equivalent. Interestingly, the determination of which undergraduate courses ought to be designated as fulfilling such requirements can become a bone of contention for scholars with appointments in history departments, in that university deans and administrators (not to mention students and parents) frequently believe that many courses in many departments review a great deal of material from the past, and therefore merit to be designated as bearing history credit for bureaucratic purposes. Professional historians will often dissent from this view, and a close, participatory ethnography of their community discussions on this apparently marginal matter would offer rich (if oblique) insight into just what historians think history actually is at any given time. Such an analysis is beyond the scope of this keyword definition, but it is notable (if confusing, given what has been said above) that work with archival sources is seldom, in fact, a component of undergraduate courses in history. Be that as it may, there is a broader fact about disciplinary history that merits particular attention in the context of reflections on inter-, trans-, and antidisciplinarity; to wit, historians tend not only to adhere to (and practice) an extremely exacting and austere form of historicism (meaning here, that orientation to the stuff of the world that privileges the temporal address—or “place in time”—of a given person, idea, phenomenon, artifact, etc. over all other features), but also to act, within learned settings, as something like the arbiters or even the police enforcers of historicism. In much the same way that philosophers might be accused of perpetually endeavoring to extend their commitment to ubiquitous noncontradiction into and even under adjacent university activities (despite conceptual contradiction being effectively constitutive of human endeavor as such), historians can be thought of as sensing themselves in possession of a comparably ineluctable and primary intellectual enterprise: putting things where they belong in time. And this despite there being a good deal of philosophical evidence that time itself does not even exist (as well as the broad anecdotal evidence that human beings live only in the present). It is not merely that historians tend to consider violations of historicist thinking “wrong”; it is also that they tend to consider considerations of things other than historicist thinking substantially misguided. Interdisciplinary encounters with historians therefore often involve the historian pointing out that what the nonhistorical colleague is doing should be historicized . In this way, disciplinary history seems particularly subject to “mission creep” when permitted cosmopolitan peregrinations within a university setting. In view of what can be descried as the fundamental limitations of historicism as an activity of mind, this kudzu-like characteristic of professional historical thought merits close scrutiny.

HUMANITIES

The plural of humanity, used to refer to the totality of mammalian creatures gathered under the taxonomic binomial Homo sapiens. In mood, the term invokes the human collective across time and space, though the word tends to emerge in aspirational contexts, frequently inflected by ethical concern (both genuine and feigned). It might be said that Homo sapiens designates not only “human beings” but also the promise of an objective or impartial designation of membership in the human community; whereas humanity designates the same collective while implicitly denying the validity or adequacy of any non-normative designation of that community. Interestingly, the plural term, humanities, has come to have a very distinct meaning at some remove from the semantic field of the singular form. In practice, the specific locution the humanities (always with the definite article; humanistic in the adjectival form) refers to a set of academic disciplines: canonically those involving the study (though not, actually, the making) of works of art, literature, and music, together with the enterprise of historical inquiry and certain traditions of philosophy. It is difficult to account for the conceptual coherence of these domains, taken as a whole, and it is further difficult to distinguish them from the sciences (which are themselves diverse). Such parsing has become more difficult as all of the disciplinary formations of the modern university have gradually accommodated themselves to a fundamentally scientific structure (meaning that all are committed to progressive knowledge production under conditions of peer review by researchers with specialized expertise in given domains, generally figured as “disciplines”). Nevertheless, the distinction between the humanities and the sciences has been a prominent feature of colleges and universities for at least a century, and the roots reach back quite deep in the intellectual traditions of the modern world (to such an extent that commentary on these matters is, and has been for some time, itself a significant academic enterprise—though in the humanities only; scientists seem, as a rule, without concern for the problem). It is sometimes pointed out that the older dichotomy in university life—the primary division that preceded the rise of the natural and physical sciences as university activities—was the humanities and the divinities, and that it is only with the substantial disappearance of the latter category of learning that the humanities found themselves juxtaposed with the sciences. The rise of the social sciences out of the late Enlightenment work of Saint-Simon and Comte has further vexed the question of what the humanities actually are and do, since substantial portions of what might have been understood as their purview (history, for instance; what comes to be thought of as anthropology; also much of the formal study of language and behavior) have come to be powerfully engaged by enterprises that eschew the language, modes, and general tenor of Humanismus. In practice, the study of human beings and their many artifacts, traditions, productions, and preoccupations has been, over the last two centuries, increasingly handled by individuals with little use for the term humanities, and relatively little connection to the hermeneutic traditions and classical master texts that create the general climate of humanistic endeavor in its university form. It can be argued persuasively that the humanities amount to a thinly veiled metaphysical enterprise (of dubious pith and integrity), resulting from a secular dilapidation of the theological programs that once gave both primary and final meaning to the category of the human. Strident antihumanisms of various species (Foucauldian, Deleuzian, Kittlerian) can be understood to be decrying exactly this woozily delusional aspect of the humanities, and the virulence of some of these attacks can perhaps be seen to reflect impatience with an air of complacency (or even wounded dignity) projected by some partisans of the humanistic tradition. At the same time, it is easy to be anxious about the long-term social and political effects of abandoning any and all efforts to spangle the category Homo sapiens with metaphysical sequins of some sort. This granted, one may well ask: Who is to be trusted with such work? Out of what shall the flash be fashioned? One is, at present, without good answers to these significant questions. But it may be that the humanities are (or will be?) relevant in this regard.

Excerpted from Keywords: For Further Consideration and Particularly Relevant to Academic Life, Especially as It Concerns Disciplines, Inter-Disciplinary Endeavor, and Modes of Resistance to the Same, authored by a Community of Inquiry, edited by D. Graham Burnett, Matthew Rickard, and Jessica Terekhov. Copyright © 2018 by IHUM Books. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.