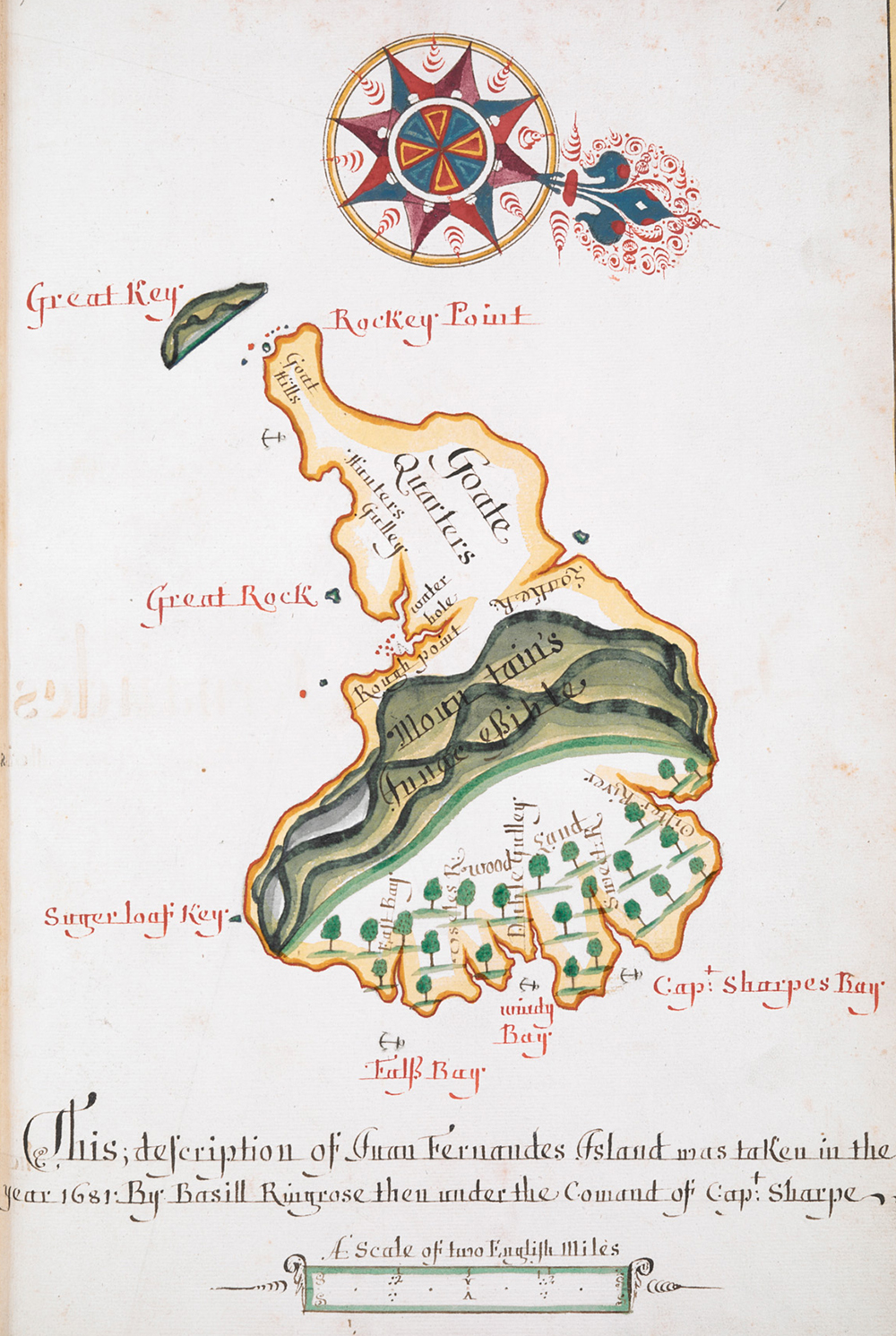

Island of Juan Fernandez, scene of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, 1860. Photograph by Helsby & Co. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

In the weeks ahead, as the world continues to reckon with and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories dealing with quarantine, unfathomable deaths, isolation, dread, and attempts to find community when the rest of the world feels far away.

Many people have turned to Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of a Plague Year in the past month to try and find historical context useful for processing our own plague year—so many that the nearly three-hundred-year-old book is selling out. Defoe’s more famous novel, Robinson Crusoe, published in 1719, may have as much to offer for those stuck at home, separated from the rest of the world, unsure what it might look like when you get to see it again, running low on food, and wishing you had more comfortable clothing options.

At this point in the book, Robinson Crusoe has been shipwrecked on his island near Venezuela for four years. He doesn’t know it yet, but he will be stuck there for twenty-four more.

I looked now upon the world as a thing remote, which I had nothing to do with, no expectations from, and, indeed, no desires about: in a word, I had nothing indeed to do with it, nor was ever likely to have, so I thought it looked, as we may perhaps look upon it hereafter— as a place I had lived in, but was come out of it.

I had now been here so long that many things which I had brought onshore for my help were either quite gone or very much wasted and near spent.

My ink had been gone some time, all but a very little, which I eked out with water, a little and a little, till it was so pale, it scarce left any appearance of black upon the paper. As long as it lasted I made use of it to minute down the days of the month on which any remarkable thing happened to me; and first, by casting up times past.

The next thing to my ink being wasted was that of my bread—I mean the biscuit which I brought out of the ship; this I had husbanded to the last degree, allowing myself but one cake of bread a day for above a year; and yet I was quite without bread for near a year before I got any corn of my own, and great reason I had to be thankful that I had any at all, the getting it being next to miraculous.

My clothes, too, began to decay; as to linen, I had had none a good while, except some checkered shirts which I found in the chests of the other seamen, and which I carefully preserved; because many times I could bear no other clothes on but a shirt; and it was a very great help to me that I had, among all the men’s clothes of the ship, almost three dozen shirts. There were also, indeed, several thick watch coats of the seamen’s which were left, but they were too hot to wear; and though it is true that the weather was so violently hot that there was no need of clothes, yet I could not go quite naked—no, though I had been inclined to it, which I was not—nor could I abide the thought of it, though I was alone. The reason why I could not go naked was I could not bear the heat of the sun so well when quite naked as with some clothes on; nay, the very heat frequently blistered my skin: whereas, with a shirt on, the air itself made some motion, and whistling under the shirt was twofold cooler than without it. No more could I ever bring myself to go out in the heat of the sun without a cap or a hat; the heat of the sun, beating with such violence as it does in that place, would give me the headache presently, by darting so directly on my head, without a cap or hat on, so that I could not bear it; whereas, if I put on my hat it would presently go away.

Upon these views I began to consider about putting the few rags I had, which I called clothes, into some order; I had worn out all the waistcoats I had, and my business was now to try if I could not make jackets out of the great watch coats which I had by me, and with such other materials as I had; so I set to work, tailoring or rather, indeed, botching, for I made most piteous work of it. However, I made shift to make two or three new waistcoats, which I hoped would serve me a great while: as for breeches or drawers, I made but a very sorry shift indeed till afterward.

I have mentioned that I saved the skins of all the creatures that I killed, I mean four-footed ones, and I had them hung up, stretched out with sticks in the sun, by which means some of them were so dry and hard that they were fit for little, but others were very useful. The first thing I made of these was a great cap for my head, with the hair on the outside, to shoot off the rain; and this I performed so well that after I made me a suit of clothes wholly of these skins—that is to say, a waistcoat and breeches open at the knees, and both loose, for they were rather wanting to keep me cool than to keep me warm. I must not omit to acknowledge that they were wretchedly made; for if I was a bad carpenter, I was a worse tailor. However, they were such as I made very good shift with, and when I was out, if it happened to rain, the hair of my waistcoat and cap being outermost, I was kept very dry.

After this, I spent a great deal of time and pains to make an umbrella; I was, indeed, in great want of one, and had a great mind to make one; I had seen them made in the Brazils, where they are very useful in the great heats there, and I felt the heats every jot as great here, and greater, too, being nearer the equinox; besides, as I was obliged to be much abroad, it was a most useful thing to me, as well for the rains as the heats. I took a world of pains with it, and was a great while before I could make anything likely to hold: nay, after I had thought I had hit the way, I spoiled two or three before I made one to my mind: but at last I made one that answered indifferently well: the main difficulty I found was to make it let down. I could make it spread, but if it did not let down, too, and draw in, it was not portable for me any way but just over my head, which would not do. However, at last, as I said, I made one to answer, and covered it with skins, the hair upward, so that it cast off the rain like a penthouse and kept off the sun so effectually that I could walk out in the hottest of the weather with greater advantage than I could before in the coolest, and when I had no need of it could close it, and carry it under my arm.

Thus I lived mighty comfortably, my mind being entirely composed by resigning myself to the will of God and throwing myself wholly upon the disposal of His providence. This made my life better than sociable, for when I began to regret the want of conversation I would ask myself whether thus conversing mutually with my own thoughts, and (as I hope I may say) with even God Himself, by ejaculations, was not better than the utmost enjoyment of human society in the world?

Read the other entries in our series: Heinrich Heine, George Eliot, Samuel Pepys, Willa Cather, Lucretius, Thomas Mann, Jack London, John Keats, Alessandro Manzoni, Giovanni Boccaccio, Frances Hodgson Burnett, François Rabelais, and Robert Louis Stevenson.