Sir Brooke Boothby, by Joseph Wright of Derby, 1781. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

During the mid-1820s, as Charles Darwin’s studies foundered, Dr. Robert Darwin eventually exhausted his patience. “You care for nothing but shooting, dogs, and rat-catching, and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family,” he exploded in a pique.

In June 1825, suspecting medicine might provide a sound career for Charles, Robert Darwin removed his sixteen-year-old son from Shrewsbury School and made him an apprentice doctor. Charles was to follow his father, older brother, and grandfather into the medical profession. But where would he train—the University of Cambridge or the University of Edinburgh? Both institutions trained doctors. Robert Darwin, as had his father, had studied at Edinburgh.

Unlike Edinburgh, Cambridge, affiliated with the Church of England, required students to pledge fealty to that denomination. In the training of physicians, Edinburgh enjoyed the superior reputation over Cambridge, with better staff and facilities, greater receptivity to new ideas from Europe, and a better hospital for graduates to obtain practical experience. And because both Robert Darwin and his illustrious father, Erasmus, had been trained at Edinburgh, Charles would arrive in “the Northern Athens” assured of a place at the tables of the city’s elite.

By late 1825 Charles was Edinburgh bound. Weeks shy of his brother Erasmus’ twenty-first birthday, he and Charles, then sixteen, traveled together from Shrewsbury to Edinburgh. Arriving in late October 1825, the brothers rented quarters in a privately owned building. Most Edinburgh students, Charles recalled, lived in “little holes in which there is neither air or light.” In stark contrast, the brothers’ rooms, on Lothian Street, were “very comfortable and near the college.”

In Edinburgh Charles and Erasmus soon called on welcoming residents who had known their father and grandfather. But Charles’ studies, by contrast, proved disappointing. “The instruction at Edinburgh was altogether by lectures, and these were intolerably dull”—particularly those by anatomist Alexander Munro. “Dr. Munro made his lectures on human anatomy as dull as he was himself, and the subject disgusted me.” Moreover, his distaste for Munro’s lectures led him to forfeit an opportunity to learn proper dissection methods. That shortcoming, along with an inability to draw, became lasting regrets.

Charles likewise abhorred the university hospital’s operating theater, where he watched “two very bad operations, one on a child.” In those days before anesthetics, to minimize trauma on patients, surgeons worked at dizzying speeds. Operating on strapped-down, screaming patients, practitioners, with dirty hands, clutching even dirtier saws, performed their procedures, as blood poured into sawdust-packed buckets beneath operating tables.

During both surgeries observed by Charles, he “rushed” away before their completion: “Nor did I ever attend again, for hardly any inducement would have been strong enough to make me do so…The two cases fairly haunted me for many a long year.”

In proposing that he and his brother live together, Erasmus had envisioned a tableau in which “we can both read like horses.” And by all indications, in Edinburgh they fulfilled that expectation. During their first term, the two removed more books from the university’s library than any other borrowers. Nonetheless, they also found time for their share (or, in all fairness, compared to their peers, less than their share) of student indulgences—from gambling to drinking, from the then popular vogue for Syrian snuff to chemistry experiments that lapsed into escapades of getting high on “laughing gas.”

The brothers also relished walks along the Firth of Forth estuary, gathering sea slugs, sea mice, and cuttlefish. Charles also decided to learn a new skill. “I am going to learn to stuff birds, from a blackamoor,” he reported to his sister Susan. His instructor John Edmonstone, a formerly enslaved black man, had been brought from Guiana by author and traveler Charles Waterton. Edmonstone, having learned taxidermy from Waterton, lived, like the Darwin brothers, on Lothian Street and conducted his lessons at the Edinburgh Museum. “He only charges one guinea for an hour every day for two months.” Moreover, Charles recalled in his autobiography, “I used often to sit with him, for he was a very pleasant and intelligent man.” Edmonstone shared firsthand accounts of life in tropical climes. Their exchanges were likely Charles’ first with a person held in bondage.

After returning from a grand tour of Europe in 1829, Erasmus elected to abandon his pursuit of a medical career. In time, Robert Darwin agreed with Erasmus that, given “his delicate frame,” the physician’s life would impose “severe strain upon [his] body & mind.” Thus, though Erasmus was but twenty-five years old, Dr. Darwin pensioned his oldest son into a life of retirement in London.

Dr. Darwin again grew worried about Charles. Weary of letters from Edinburgh asking for money, he found even more disturbing reports of his son’s lackluster academic performance. But for the diagnosed condition, the physician also had in mind a possible remedy: “My father,” Charles recalled, “perceived or he heard from my sisters that I did not like the thought of being a physician, so he proposed that I should become a clergyman”—more specifically, a rural parish clergyman.

Robert Darwin knew that rural parish clergymen in the wealthy Anglican church often enjoyed enviable lives with undemanding responsibilities, comfortable rectories, and abundant time to pursue other interests—including natural history. Many of that day’s prominent naturalists in England held such sinecures. Robert Darwin’s latest career suggestion for Charles arose less from any belief that his son was particularly suited for the ministry—more from fears of what Charles, now eighteen, might otherwise become: “He was very properly vehement against my turning an idle sporting man, which then seemed my probable destination.” Charles later admitted that he had grown “convinced from various small circumstances that my father would leave me property enough to subsist on with some comfort.” And that “belief was sufficient to check any strenuous effort to learn medicine.”

After doing some research and pondering his own beliefs, Charles decided his newer perspectives on natural history could be reconciled with Anglicanism. He withdrew from Edinburgh University without taking his degree and, on the threshold of what his father feared was his wayward son’s final chance at respectability, was admitted to Cambridge University in October 1827.

Charles soon realized he had a problem. His studies at Cambridge required a familiarity with classical languages; and, upon reflection, he realized that “I had never opened a classical book since leaving school.” To refresh his knowledge, Dr. Darwin hired a tutor to work with Charles in Shrewsbury through the fall. Thus, instead of moving to Cambridge in October as he would have otherwise, his arrival there would be postponed until January of the new year.

Because he arrived midway in the academic year, lodgings were unavailable in Christ’s College. So, until the following October, when quarters there would be available, he rented rooms above a tobacco shop on Sidney Street. Academically, those first months proved promising. “I soon recovered my school standard of knowledge, and could translate easy Greek books, such as Homer and the Greek Testament with moderate facility.” Alas, however, that promising trajectory soon surrendered to a familiar outcome. “During the three years which I spent at Cambridge my time was wasted, as far as the academical studies were concerned, as completely as at Edinburgh and at [Shrewsbury] school.”

Charles had registered for the ordinary bachelor of arts degree, the conventional curriculum that preceded theological training. His initial curriculum thus included elementary mathematics, geometry, and algebra—an immersion during which he surprised himself by the “delight” he found in Euclid. He also found unexpected pleasures in various Greek and Latin texts, and a seminal book of that day, Anglican theologian William Paley’s Natural Theology, or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity. Paley’s work emphasized the idea of organisms adapting to their environment.

“The logic of this book,” Charles recalled, “gave me as much delight as did Euclid. The careful study of these works, without attempting to learn any part by rote, was the only part of the academical course which, as I then felt and as I still believe, was of the least use to me in the education of my mind.”

On March 24, 1830, Charles passed his “Little-go,” the first of two examinations required for his degree. Ten months later, between January 14 and 20, 1831, he completed his final examinations—three days of written papers that, after being marked, landed him tenth among 178 degree candidates not seeking honors. He later attributed the unexpected triumph to “answering well the examination questions in Paley, by doing Euclid well, and by not failing miserably in classics.”

More broadly, historian Peter J. Bowler observed, “Darwin’s scientific training at Cambridge was thorough, even if it was gained outside the curriculum.” In many passages of Charles’ Autobiography, he paints a dark view of his three years at the Anglican university. Laments the son of the abstemious Robert Darwin, “My time was sadly wasted there and worse than wasted…and we sometimes drank too much.” Nonetheless, he allows, “There were some redeeming features in my life at Cambridge”—“Upon the whole the three years which I spent at Cambridge were the most joyful in my happy life; for I was then in excellent health, and almost always in high spirits.”

A friend, John Maurice Herbert, brought Charles into a “musical set,” musicians who socialized and attended concerts together. Though Charles played no instrument, through “these men and hearing them play, I acquired a strong taste for music.” Another friend, Charles Thomas Whitley, who had been a classmate at Shrewsbury School, “inoculated” him “with a taste for pictures and good engravings…I frequently went to the Fitzwilliam Gallery [in Cambridge], and my taste must have been fairly good, for I certainly admired the best pictures, which I discussed with the old curator.” The Glutton Club, a weekly supper gathering of Charles and four other students, had a less conventional pursuit. With dishes prepared by the college’s kitchen staff and washed down with generous quantities of port, the club devoted itself to the consumption of “strange flesh”—wild animals, principally birds, including bitterns and hawks. Held in its members’ respective rooms, the meals came to an ignominious end the night they attempted, with unspecified disastrous consequences, to eat “an old brown owl.”

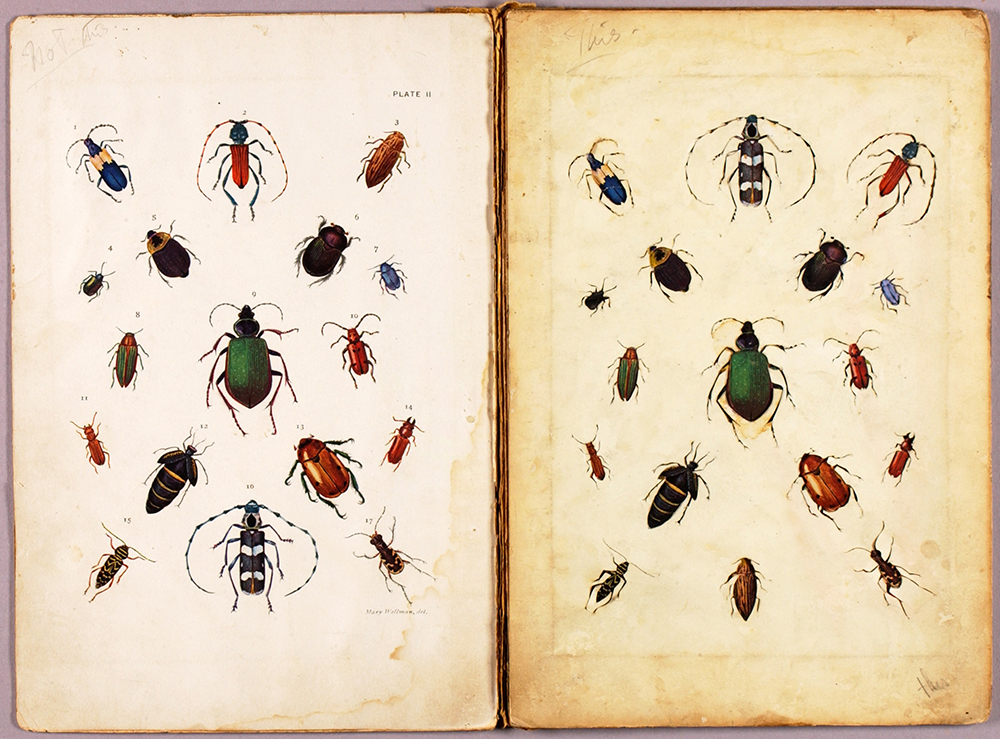

But no interest Charles took up at Cambridge gave him “so much pleasure as collecting beetles.” As industrialism transformed life across England, practitioners of “beetling”—weary of cities fouled by the “dark Satanic mills” cursed by poet William Blake—found sanctuary in forests and other natural settings. There, armed with nets and alcohol-filled bottles, the fad’s zealots searched for their quarry beneath rocks, tree bark, and fallen leaves. A competitive spirit drove beetling, and few pursued it as aggressively as William Darwin Fox, the naturalist who introduced Charles to the craze. A second cousin four years younger than Charles, Fox was, like his kin, enrolled at Christ’s College, preparing for the ministry. Soon spending hours in the field together, Fox imbued Charles’ insect collecting with a new sophistication.

Moreover, until those Cambridge days, Charles—curiously, considering his early acquired zeal for killing birds—had retained a concern for his entomological prey’s mortality. At age ten, after consulting a sister, “I concluded that it was not right to kill insects for the sake of making a collection.” Under Fox’s tutelage, however, Charles, abandoning such concerns, became a devotee of An Introduction to Entomology, a four-volume work by William Spence and William Kirby that served as the pastime’s bible (a work Charles later took on his Beagle travels and used frequently). Moreover, during his Cambridge days, “very soon” Fox “armed me with a bottle of alcohol, in which I had to drop any beetle which struck me as not of a common kind.”

On one occasion, while tearing a strip of old bark from a tree, Charles spotted “two rare beetles and seized one in each hand.” Moments later, “I saw a third and new kind, which I could not bear to lose, so that I popped the one which I held in my right hand into my mouth. Alas it ejected some intensely acrid fluid, which burnt my tongue so that I was forced to spit the beetle out, which was lost, as well as the third one.” Eventually, using funds his father provided, Charles “employed a laborer to scrape during the winter moss off old trees and place [it] in a large bag, and likewise to collect the rubbish at the bottom of the barges in which reeds are brought from the fens [marshes], and thus I got some very rare species.”

Indeed, it was beetling that, in 1829, first landed the name Charles Darwin in a scientific publication. The reference appeared in Illustrations of British Entomology, a series authored by English naturalist James Francis Stephens. Describing several beetles recently collected by Charles, the entry was brief. But, as he later recalled, “No poet ever felt more delight at seeing his first poem published than I did at seeing in Stephen’s Illustrations…the magic words, captured by C. Darwin, Esq.’ ”

From Odyssey: Young Charles Darwin, the Beagle, and the Voyage that Changed the World by Tom Chaffin, published by Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2022 by Tom Chaffin. All rights reserved.