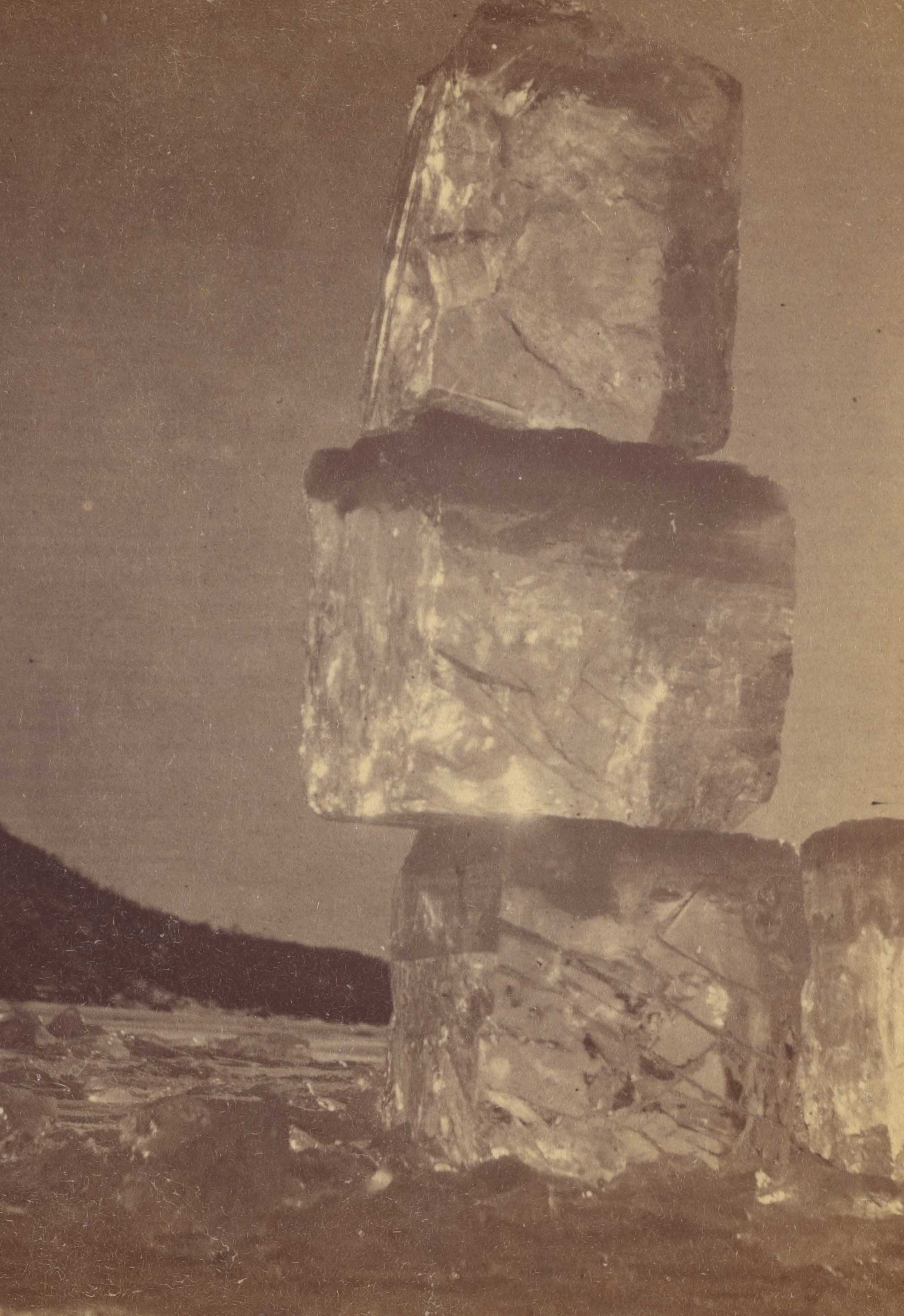

Minnesota Ice Harvest, by Charles A. Zimmerman, c. 1870. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

As temperatures keep rising in the twenty-first century, humans continue looking for new ways to stay cool. The challenges of climate change might make the problem seem novel, or at least more extreme, but our latest efforts to stave off intense heat benefit from thousands of years of desperate innovations. Man-made cooling, then as now, is often out of reach for those living and working in the hottest temperatures. But it did exist for an elite few. As science writer Tom Jackson noted in Chilled, his 2015 history of refrigeration, ancient Mesopotamians created some of the first verified cooling spaces.

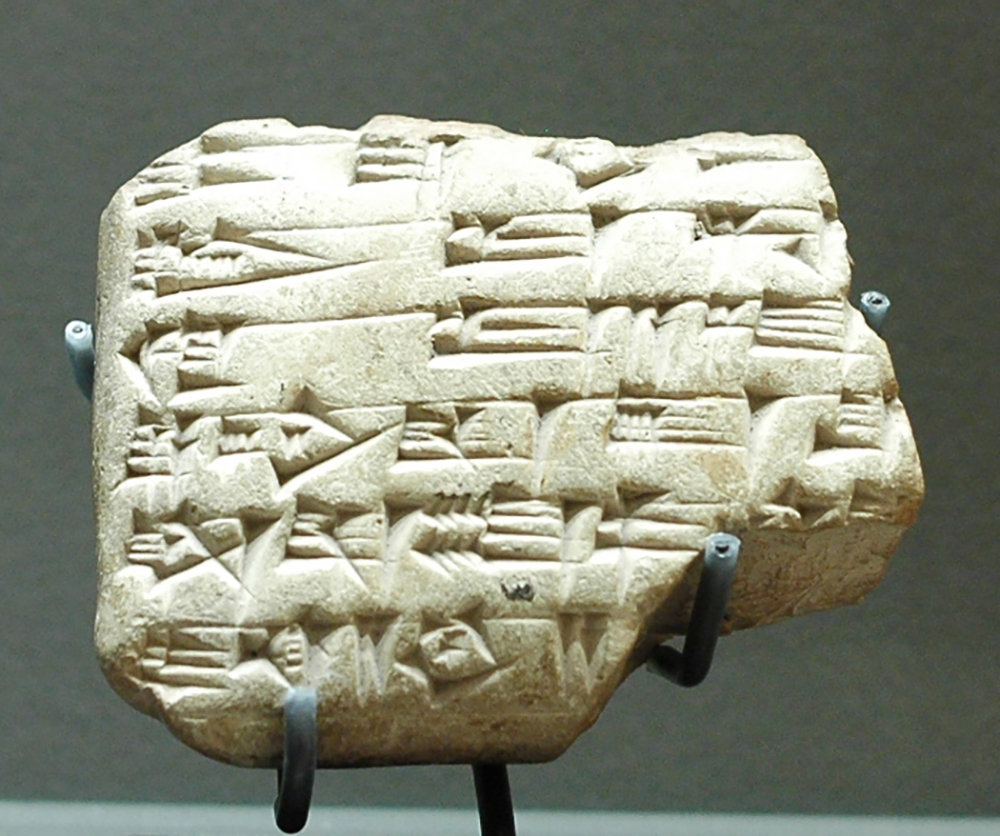

Treasure troves of correspondence, written in cuneiform script on clay tablets, reveal how ancient kings constructed icehouses specifically designed for the purpose of cooling beverages or food—the ultimate sign of privilege. Archaeologists noticed large decreases in rainfall and increased aridity across Mesopotamia in the late third millennium bc and into the early second. If these events survived in cultural memory, perhaps it’s not surprising that the use of ice, especially icehouses, became a point of pride for royals.

Perhaps the earliest reference to icehouses comes from Shulgi, who held sway in the Sumerian city of Ur at the tail end of the third millennium bc. In Mesopotamia, it was common for each year of a monarch’s reign to be named after significant events that took place in that time period. Year 13, for Shulgi, was dubbed “Building of the royal icehouse/cold-house.” Jackson suggested such buildings might have been “timber-lined holes in the ground” designed to keep ice brought down from the mountains “cool and secure.”

Similar references remained sparse for two centuries after the year of the icehouse. But Shulgi was apparently an early adopter of a trend that began to flourish in the eighteenth century bc, when icehouses began appearing in city-states spanning the Fertile Crescent. Mari, located in modern Syria, grew in importance from Shulgi’s time onward, reaching its zenith under its final and greatest king, Zimri-Lim. The Mari chieftain Yaggid-Lim had founded the famous Lim dynasty around 1830 bc. His son Yahdun-Lim succeeded him, only to be defeated by a warlord called Shamshi-Addu (also known as Shamshi-Adad I).

Shamshi-Addu assumed control of a vast swath of territories north of Babylonia, uniting them into what modern scholars have dubbed “the kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia.” He appointed his son Yasmah-Addu his viceroy in Mari. In a letter prayer to the god Nergal, Yasmah-Addu justified his own claim to Mari by declaring his predecessors impious men. (Yasmah-Addu probably was not much better than previous kings. In surviving letters to Yasmah-Addu, Shamshi-Addu exclaimed in frustration, “Are you a child, and not an adult?”)

This dynasty’s rule over Mari ended not long after Shamshi-Addu’s 1776 bc death, with Yasmah-Addu being tossed out. Zimri-Lim, who claimed to be Yahdun-Lim’s son, soon recaptured control of Mari. During his reign, the city’s palace was renovated in splendid fashion, complete with a mural depicting his investiture as king.

King Zimri-Lim claimed to have established icehouses at his provincial power centers, including Saggaratum, capital of the province of the same name. Its internal importance was such that Zimri-Lim named one of his regnal years after his conquest of the town. Knowledge of icehouses themselves have survived primarily through written records, so the scholarship on what they looked like remains an educated guessing game.

Historian Izak Cornelius suggested that icehouses in the time of Zimri-Lim would have contained subterranean vaults covered with domes and arches. Assyriologist Jack M. Sasson posited that Zimri-Lim’s icehouse might have contained long, low rectangular ponds. During the winter, the pools, filled with water, would then lose heat, while the walls would reduce any warmth coming in. No matter how much heat came through the earth, the pool’s contents should have been able to freeze. But, as Jackson noted, “the earliest solid evidence for” deliberately freezing shallow pools “comes from ancient Persia,” and Sasson stated he based his own suppositions on Iranian examples.

At Terqa, north of Mari, Zimri-Lim commissioned a dedicatory inscription documenting his construction of an icehouse. In a translation published by Sasson in 1984, the monarch declared his name and lineage as “Zimri-Lim, son of Yakhdun-Lim, king of Mari, of Tuttul and of the Hana Land.” Sites like Terqa were ruled by governors reporting to the king. In each regional capital, Zimri-Lim might have maintained a court and retainers building icehouses in these important outposts could have served as physical reminders of the king’s power when he was away. After listing his titles in the inscription, Zimri-Lim bragged that he was making history as the “builder of an ice-storage facility which never before has any king built on a bank of the Euphrates.” The presence of the river would have provided ample supplies of water to freeze—or a way to transport blocks of ice. And whenever Zimri-Lim visited Terqa while touring his provinces or on campaign, he could be assured of a cold beverage or two.

The Terqa icehouse’s physical remains have not yet been discovered, as archaeologist Giorgio Buccellati noted in 1983. But surviving foundation records tell us that the building measured six meters by twelve. As described by Jackson, it featured “channels to remove any melted water and so prolong the life of the ice.” Perhaps it was located in a cellar of the Terqa palace, maximizing royal proximity to the precious commodity for the royal court there.

When Zimri-Lim was away, a Mari official named Manatan updated him about affairs at home. “About the ice my lord charged me,” he wrote to the king, “I was not negligent. The water reservoir at the Baliḫ Gate is full.” After the pools of water froze, the ice would likely be cut into large but manageable blocks and placed into storage pits until they were ready for transportation. Smaller chunks could be used to cool wine for the king and his court to drink.

Once the ice left its temperature-controlled home, however, officials struggled with the reality: no one had yet invented a portable icehouse, or cooler. In surviving correspondence, the governor of Terqa, Kibri-Dagan, complained to Zimri-Lim about how hard it was to keep the ice from melting. “I fear that when I translate the ice to another locality as my lord wrote,” Kibri-Dagan warned, “it will become liquid.” He even asked the king to send someone to come and oversee all things frozen at Terqa.

Zimri-Lim wasn’t the only king to keep things cool around this time. Records from other cities indicate that it was in vogue for high-ranking individuals to have regular supplies of ice.

Shamshi-Addu once sent Yasmah-Addu to get some ice—or rather, as Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley related it, he wanted his son’s servants to find and clean it. Shamshi-Addu asked, “About collecting ice: is it good when porters have to bring ice from twenty or forty miles away?” He added that Yasmah-Addu should order other servants to “collect the ice! Let them wash it free of twigs and dung and dirt.” Water could collect all sorts of grimy things, so it was imperative to make sure nothing inedible was present before it was frozen. Concern over the water getting befouled indicates that it was exposed to the elements, perhaps collected from the mountains or in a large external pool.

Before Zimri-Lim reinstated the Lim dynasty’s rule, Yasmah-Addu had allied himself with powerful lords like Aplahanda, king of Carchemish, on the modern Turkish-Syrian border. In a letter, Aplahanda told Yasmah-Addu that there was “plentiful” ice in the city of Ziranum and advised him to “set some of your servants to guard it.” As a result, Yasmah-Addu could receive ice whenever he wanted it, but the necessity of a guard indicated that this was a precious commodity, one many wanted but few could access. Aplahanda also offered Yasmah-Addu fine wines; perhaps either man would have enjoyed chilled drinks in the shade of a tamarisk.

Ice would have been an expensive and time-intensive gift to produce: perfect for those trying to impress. Following his lord Zimri-Lim’s commands, Yasim-Sumu, accountant and estate manager at Mari, recorded that he dutifully gave visitors from Elam, located in what is now southwestern Iran, “a jar of wine, two fine male sheep, and the ice that was brought from my lord.” There is no reference to an icehouse, but how else the material might have been stored is unclear.

Ice was also a gift worthy of a goddess in neighboring kingdoms. At Tell al Rimah, in northern Iraq, archaeologists uncovered an archive belonging to a woman named Iltani. She and her husband, King Aqba-Hammu, reigned over the kingdom of Karana as vassals of Hammurabi of Babylon. In antiquity, Tell al Rimah might have been one and the same with one of two cities: the urban center also called Karana or its “sister city” of Qatara, as Assyriologist Nicholas Postgate argued in 2013.

Aqba-Hammu penned a missive to Iltani about the ice stores in Qatara. He told his wife, “Let them unseal the ice of Qatara. The goddess, you, and Belassunu drink regularly, but make sure that the ice is kept safe.” Perhaps Belassunu was Iltani’s sister or another close relative. The finest vintages of wine, complete with an ice cube or two, were evidently of sufficient value to be an offering to a deity.

Zimri-Lim may well have offered similar iced beverages to the god Dagan. A patron deity of Terqa whose name appears on the king’s icehouse dedicatory inscription, he was widely worshipped in Mari and its surroundings. Dalley observed in 1984 that Dagan “guarded the road from the southeast into Syria,” so any kings moving westward would likely propitiate him for a good journey. The twelfth year of Zimri-Lim’s reign was dubbed "the year Zimri-Lim dedicated a great throne to Dagan of Terqa.” In a letter, a Mari official named Rip’i-Lim declared the deities Dagan and Itur-Mer helped Zimri-Lim “triumph over his enemies.” Were these divine interventions contingent on the promise of a heavenly post-victory drink? Zimri-Lim clearly thought the enticement must not have hurt.

Icehouses never became fashionable for anyone but the most elite. Few except kings or governors would have the resources—money, labor, space, materials, time—to construct a building just for freezing or storing ice harvested from the mountains. While creating or cultivating ice resulted in pleasant coolness for a select few, most people beat the heat in more mundane ways. As Assyriologist Marc Van de Mieroop pointed out in 1997, urban homes were clustered closely together, which meant fewer walls would get direct sun exposure. Some houses had rooms only accessible through a courtyard. During the day, hot air would rise, allowing currents of lower temperatures to sweep in; at night, cool air would proliferate. People likely dozed on roofs to enjoy a good breeze.

Expensive fridges may have gone out of fashion after the early second millennium bc; they do not appear often in extant written records until thousands of years later, in Persia. When Zimri-Lim’s ally-turned-rival Hammurabi conquered and destroyed Mari, antiquity lost one of the greatest advocates for icehouses.

Hammurabi and his heirs didn’t seem to prioritize this cool tradition and moved on to codifying laws and flexing military might. They may well have used ice but decided against spending money to build a house specifically for it. Icehouses did appear elsewhere, apparently independently. Archaeologist He Nu posited that an icehouse existed at the ancient Chinese site of Taosi, dating to 2300-2100 bc, while the remains of such a building were discovered in the first-millennium-bc city of Yongcheng. But it’s most likely thanks to ancient Persia that ice eventually exploded in ancient Greece and Rome. By the fifth century bc, the Persians mastered building yakhchāl (ice pits) and yakhdan (ice container), along with windcatchers; trade and military conquest, such as Alexander the Great’s campaigns, helped spread such cooling technologies.