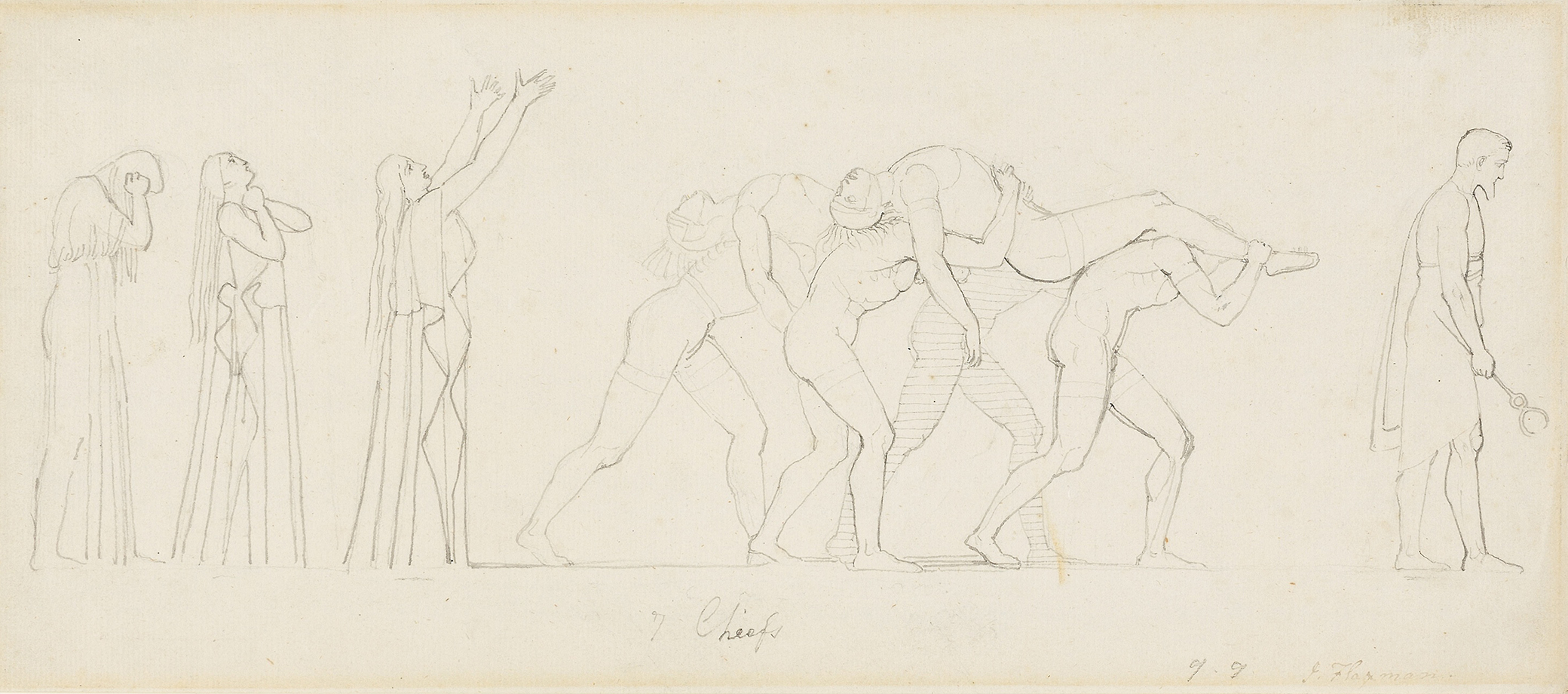

Seven Chiefs Against Thebes, by John Flaxman, late eighteenth to early nineteenth century. The Art Institute of Chicago, Sidney A. Kent Fund.

In the decades on either side of 500 bc, the annual performance of tragedies, satyr dramas, and later comedies at religious festivals in honor of Dionysus was becoming an integral element of the Athenians “doing” their brand of democracy. Democracy in ancient Greece was not just a matter of institutions, but also a matter of deep culture. By attending the theatrical performances—and the Athenians took many steps to ensure that poverty would not be a decisive obstacle to attendance for anyone—the citizens in the audience, no less than the actors and chorus members below them onstage, actively performed their democratic duty and roles.

At the same time they learned—especially but not only through the tragic suffering of others (pathei mathos, “learning by/through suffering,” a phrase used by Aeschylus in the Agamemnon)—what it was to be fully human in a fully political community, one in which direct self-government was a matter of daily life, not just occasional ritual. This, of course, raises a question. Why was it that the mythology—and almost all Athenian tragedies were set in the dim and distant, more or less fabled past—of ancient Thebes in particular held such an appeal as raw material for Athenian tragic dramatists in the fifth century bc, not least among the “big three,” later canonized by the Athenians themselves, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides?

In addition to Aeschylus’ version of the “Seven Against Thebes” myth, performed probably in 467 bc, and Euripides’ Bacchae of 405 bc, by an accident of survival and preservation there also exist three Theban plays by Sophocles, three separate tragedies set in ancient Thebes, which are too often misdescribed—or mis-sold—as his “Theban trilogy.” This is doubly unfortunate. Ancient Athenian dramatists were indeed required to write sets of three tragedies for competitive performance at the annual Great or City Dionysia play festival held in late March or early April at the foot of the Acropolis. But only rarely was the set of three an actual trilogy in the strong, connective sense—Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy of 458 bc is the sole classic, extant example. Moreover, they did not write only those three tragic plays: if chosen by the Athenian official responsible (the “Eponymous” Archon, who was selected by random lottery and not for any special dramatic expertise), they also had to write and have staged a fourth play, a (more or less comic) satyr drama, conceived and performed as a relieving, releasing coda.

Sophocles’ three surviving Theban plays each formed a part of three quite separate sets of three tragic dramas, and they were written and performed over a period of some forty years, a very long generation: the Antigone in probably 441 bc, the Oedipus Tyrannus in 430 or 429 bc, and the Oedipus at Colonus, first performed posthumously (Sophocles died, in his nineties, in 405 bc) in 401 bc. Aristotle, who was not an Athenian and may not have been the Greeks’ greatest theater critic of all time, was convinced that the Oedipus Tyrannus was the perfect, the canonical, tragedy. Certainly it ticks all the familiar boxes—of unintended consequences, human (mortal, fatal) error of identification and judgment, of overall inscrutable, indefeasible divine power, of murder, incest, suicide, a catalogue of altogether horrifying death and destruction. Everything gone awry. And that, of course, is one part of the answer to the question about the peculiarly insistent appeal to Athenian poet dramatists and audiences of specifically Theban mythical themes. How sweet (the ancient Greek metaphor of choice, sweet as honey) to revel in the spectacle and imagination of your enemies being under the cosh, and so often a self-inflicted cosh at that.

But there was more to it—and this can be best brought out by reference to another of Euripides’ tragedies, his Suppliant Women, which was set in the famous sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis just to the west of Athens. Athenians were fond of suppliant plays—Aeschylus’ Suppliant Women happens to be extant, probably dated 463 bc. In it he had been daringly quasi-anachronistic, and not for the first time. He has Pelasgus, who if historical would have been the hereditary king of Peloponnesian Argos, behave as if he were but a constitutional monarch, obliged to consult and abide by the wishes of the so-called people (demos) of Argos.

They duly meet in open assembly to express their opinion on whether Argos should or should not receive as suppliant strangers in the midst of their community—and therefore to be protected under a religious sanction—a large number of foreign refugee women from Egypt, the fifty daughters of Danaus. By an overwhelming majority they vote “Yea,” which decision King Pelasgus quasi-anachronistically, and disingenuously, refers to as an act of the kratousa kheir of the demos, the “decisively empowered/empowering hand of the people.” In 463 bc actual Athenians took some of their public political decisions by open majority vote, raising their right hands (kheirotonia), which were then either counted individually or more usually “told,” that is, guesstimated. That was the kratos of the demos that together went to make up a very newfangled demo-kratia, hardly something in existence in supposedly prehistorical Argos.

Likewise, there is a famously democratic passage in the 423 bc Suppliant Women of Euripides. A Theban herald—what we would call an ambassador or official envoy—has come to Athens from King Creon to demand officiously that Athens, that is to say, its sole ruler King Theseus, surrender to him a group of Argive suppliant women, whose cause is aided by the father-in-law of (dreaded traitor) Theban Polyneices. Theseus of Athens, not to be outdone by Pelasgus of Argos, in fact outdoes him by a considerable distance—which for him was not difficult, since over the course of the fifth century bc he had been gradually transmogrified from a Bronze Age, monster-slaying hero into a pacific founder of nothing less than the Athenian polis. This foundation he was supposed to have effected via the mechanism of sunoikismos (synoecism), the literal “housing together” of all the demoi (villages) of Attica into one unified and centralized political entity, “the Athenians,” with its capital in Athens focused around the mighty Acropolis, or high city. Even the supposedly critical and rational Thucydides seems to have accepted that this city-founding Theseus had actually existed. Who better therefore than the stage character Theseus to respond, witheringly, to the Theban herald with a magnificent declaration of democratic, ideological intent?

The herald begins his pitch badly, in Athenian democratic terms the worst possible way. Who, he demands, is the despotes of this land? As if he didn’t know who ruled Athens, he asks in effect who is the unaccountable lord and master, the despot, of the Athenians? To which Theseus replies that there is no such “despot” here: that is not how our community, unlike your Thebes, manages its politics of self-government. The Theban royalist herald, however, will have no truck with the notion that the masses—the “mob”—can possibly have any legitimate public political say. But they do, rejoins Theseus, and quite rightly so too. In John Davie’s admirably sober and accurate prose translation:

No enemy is more dangerous to a city than a monarch, for then, firstly, laws for all citizens do not exist and one man enjoys power, appropriating the law as his own possession. This means an end to equality. But when laws are written down, the weak and the rich man alike have their equal right…Liberty speaks in these words: “Who with good counsel for his city wishes to address this gathering?” Anyone who wishes to do this gains distinction; whoever does not, keeps silent. Where could a city enjoy greater equality than this?

Moreover, in 424 bc, just a year before the Suppliant Women was first performed, Thebes had visited some sort of destruction also upon pro-Athenian Boeotian Thespiae, before soundly trouncing an Athenian army at Delium, in Boeotia, after a badly mismanaged Athenian invasion. Besides the relief of laughing at Aristophanes’ Socrates-guying Clouds, one of the three offerings in the Comedy (komoidia) section of the Dionysia festival in 423 bc, the audience could thus vent their spleen upon Thebes and all its antidemocratic works in tragic vein.

Excerpted from the new book Thebes: The Forgotten City of Ancient Greece by Paul Cartledge, published by Abrams Press. Copyright © 2020 by Paul Cartledge.