Panel with striding lion, Babylonian, c. 604 bc. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1931.

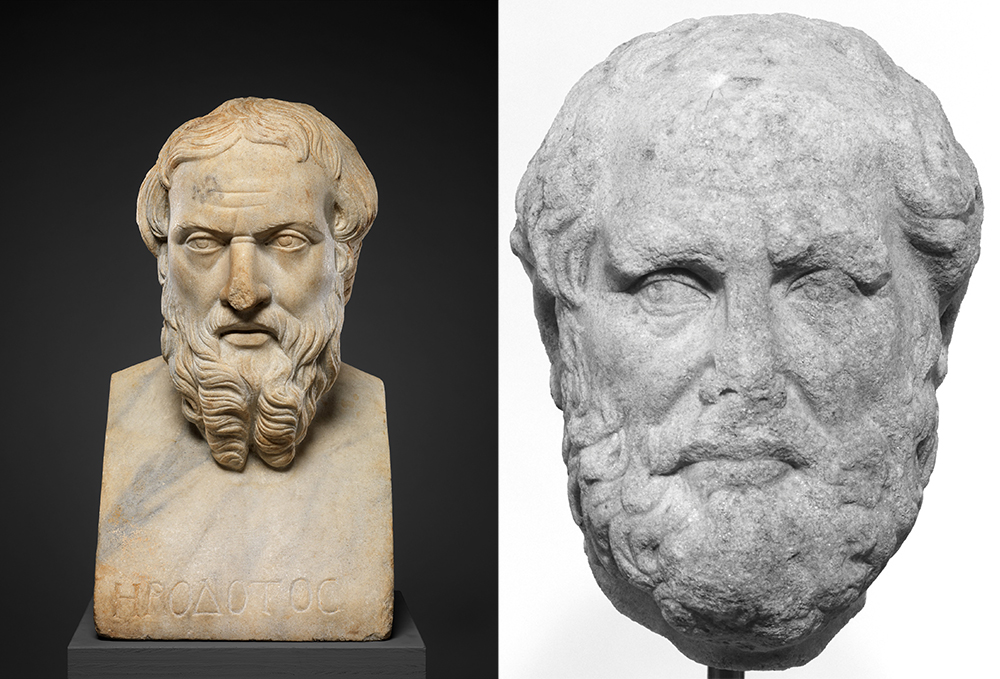

History as we know it appeared when someone went beyond Homer to supplant fiction with fact. The first person to show those qualities in an extended narrative was Herodotus.

In his celebrated Histories, the first fully wrought Western work of prose about any subject that has survived in its entirety, Herodotus wrote about the wars that broke out in 480–479 bc between Greeks and (as he and his contemporaries called them) “barbarians,” the non-Greek peoples like the Persians, among whom Herodotus lived before moving to Athens. His intentions differed from those of the rhapsodists whose traditional accounts of the Trojan Wars had reached their peak with Homer and who had peopled their tales with divine and mythological characters.

He set out to tell of “the causes that led them to make war on each other.” It was a simple aim but, as the future would reveal, one fateful with promise. Herodotus was inaugurating the writing of history. And by writing in prose, he separated the province of history—whether purposefully or not we do not know—from the cultural dominance of imaginative literature. Not for nothing did Cicero call him “the father of history.”

What made Herodotus a historian and not a mere chronicler of human acts were the particular elements, ones not seen before, he brought to his work. He was by nature a geographer, anthropologist, zoologist, ethnographer, and folklorist as well as historian. Traveling widely, he spoke with contemporaries to secure evidence of what had happened before and during the Persian Wars, conflicts that had taken place during Herodotus’ youth and within the living memory of many whom he interviewed. In doing so, he inaugurated the active, engaged historical method that, while long serving as one among many ideals of historical research, also created what would prove a fruitful tension between on-site and archival work.

A participant in a polytheistic culture, Herodotus comfortably reported on claims about gods’ interventions and the oracle at Delphi but gave to historical figures—humans known to have lived—their full scope of human qualities. Even though he was unable fully to dismiss the gods’ influence over human affairs, as philosophers had already started to do, Herodotus began to remove them as causative agents on earth. Causation, he thought, lay in human events and decisions, not with capricious deities, and he thus laid down one of the permanent criteria by which a work is judged to be history or not: he sought to explain, not just to record, how the Persian Wars had come about. And while writing as a Greek who brought to life in his pages the public realities of Greek city-states, Herodotus echoed Homer’s evenhanded treatment of the characters in his tales by seeking to balance his own loyalties to Greece with a tolerant understanding of the Persians and other peoples who filled his history. Herodotus purposefully aimed to run down the wars’ origins using the widest range of methods, evidence, and explanations available to him. He also tried to assess the wars’ significance for Mediterranean civilization. He was the first person known to us to make study of the past the subject of rational inquiry.

Herodotus was a historian because he described his sources, such as what he heard and saw among the people whom he encountered and whom he had learned from (“There were other things, too, which I learnt at Memphis in conversation with the priests of Hephaestus”). He also told his readers how distant he was from those sources (for instance, second- or thirdhand). Here was someone who recounted history for those who had not been present—an achievement in itself—while at the same time pioneering in historical methods.

Like a skeptical reporter, in the Histories Herodotus also lifted his eyebrows at the claims and stories of the past he found wanting in credibility and plausibility, and he felt free to reject them. Dismissive of much myth, he inaugurated the displacement of legend by the ascertainment of fact. In mild rebuke of Homer, he corrected what he thought were the errors of the great poet who had lived (or so we think) four hundred years earlier. A skeptic, he felt free to offer his own judgments while accepting responsibility for explaining how and why he arrived at them. Words and phrases like “perhaps,” “they say,” “according to some authorities,” and “so far as knowledge goes” filled his account. By offering a history that differed from the epics and chronicles of events that preceded his work, Herodotus was taking the first steps toward trying to alter his contemporaries’ understanding of the past. He was also suggesting that different versions of the past could exist. His Histories made history a practice in which historians would assess sources, seek confirming or new evidence for what they wrote about, offer fresh views of the past, and feel free to criticize others for their errors, limitations, and commitments. Simply by taking up an early version of field research, Herodotus inaugurated the future course of historical inquiry.

Right at the creation of Western historiography, then, the seeds of what would become the revisionist tradition within the writing of history took hold. Once Herodotus had created historical criticism, it could never be suppressed, nor could anyone ever escape its influence. Thus it was that not even this first great historian could avoid attack from his successors any more than he could resist questioning the work of his predecessors. It did not take long for Herodotus himself to be assailed and his Histories to be derided. So influential was the criticism of his work that his Histories were effectively ignored for two and a half millennia.

It was Herodotus’ younger contemporary Thucydides who inaugurated their dismissal. The Histories were, Thucydides scornfully wrote, “a prize essay to be heard for the moment,” a work not to be studied and one unlikely to endure. “So careless are most people [that is, Herodotus] in the search for truth,” wrote Thucydides, “that they are more inclined to accept the first story that comes to hand.” His own views, by contrast, could “safely be relied on.” Not for him was history to be “attractive at truth’s expense.” In throwing down the gauntlet to anyone who did not adopt his own different focus and possess his own distinctive intentions, Thucydides turned interpretive differences into interpretive battles and opened what has proved to be a never-ending struggle over the past—over what is good history, useful history, and artful history and, above all, over what are the “correct” interpretations of past events, the “correct” subjects of inquiry, the “correct” evidence to use, and, above all, what are the “correct” aims of written history. By establishing criticism of predecessors as a legitimate practice in moving historical thought forward, Thucydides’ words also served notice to his successors that the struggle over how to do history and what the past should mean would not always be good-natured and free of conflict.

Born between 465 and 460 bc into the wealthy Athenian elite, Thucydides was less the curious, disinterested investigator that Herodotus was and more a man of action and strategic thinking, one whom today we would call a defense intellectual, someone caught up in the events he sought to understand. A youth when the first Peloponnesian War—a civil war between Athens, Sparta, and their Greek allies—began in 460 bc, he wrote his unfinished work in his twenties after having led a defeated Athenian naval force and then been exiled. While striving hard to be objective, he brought a participant’s observations, associations, and commitments to bear on what he wrote. In his tight focus, his rationalism, his sternness, and his stated aspiration to be objective, Thucydides turned history in the direction against which all subsequent histories, ones that follow other approaches and have other aims, have had to contend.

For instance, his classic History of the Peloponnesian War was devoid of gods quarreling away on Mount Olympus and intervening in human affairs; instead, Thucydides grounded his tale entirely among living humans, and he thought prayer of no help in distress. This was not the last time historians would try to banish all deities and unverifiable claims from their accounts, but it was the first time one made the attempt and thus of enduring significance.

Equally fatefully, and implying that he felt daunted by the hope of knowing how and why everything had happened, Thucydides took as his subjects a far more limited set of topics—warfare, politics, statecraft, and diplomacy—than had Herodotus; one explained war and the relations among states, he thought, not by looking at religious belief and burial customs but rather by examining military battles and military leadership. He also inaugurated the practice of contemporary history by writing of current events and of the war in which he had fought, thus bringing into written history the elements of memoir. A historical portraitist, he made major contemporary figures like Pericles—for whom he wrote celebrated speeches whose contents and lessons continue to bear reading—play leading roles in his work. Humans (at least male humans) and not large, abstract forces, he believed, made history. All of this placed Thucydides, like Herodotus, among the very first to sense that a historian’s task is to reconstruct the past as it happened, not as others wanted to believe it had happened.

With similar consequences, Thucydides believed history to be a kind of human “science” whose study would provide warnings and lessons to its students. For example, given to generalizations, he argued that wars usually commence from an absence of forethought. “Action comes first, and it is only when [people] have already suffered that they begin to think.” Most significant, he intended his work to be “a possession for all time. Future ages will wonder at us, as the present age wonders at us now.” To him, historical knowledge was an instrument for use, one indispensable to those who would master human affairs and statecraft and would direct public policy.

Like Herodotus, Thucydides wrote of individual leaders, but unlike his predecessor he tried to plumb the nature of the leadership and statecraft his leaders employed; he spent few words on the common people. This led him to draw historical truths about man’s nature, good and evil, and the workings of fortune from what he observed. He had no difficulty dismissing popular causal explanations for what he believed to be stronger ones. (The fundamental cause of the Peloponnesian War, “though it was the least avowed,” he wrote, “I believe to have been the growth of the Athenian power, which terrified the Lacedaemonians and put them under the necessity of fighting.”) He sought to place his work on a firm factual basis and exclude anything that could not be verified. Thucydides thus laid claim to the utility of historical knowledge for understanding human affairs. And he inaugurated the long battle between historians who emphasize large forces over vast reaches of space and time and those who focus on more limited affairs. In opening this fissure between historians of what the French call l’histoire totale and those who focus on discrete, closer events, or l’histoire événementielle (“event history”), he changed the subject of historical inquiry from society and culture (Herodotus’ interests) to war and foreign relations.

In undertaking that last effort, Thucydides had his most lasting impact. With only a few exceptions, like Tacitus’ writings on the German tribes, not until the eighteenth century would people studying the past again turn their attention to society and culture and try to recapture for history the realities of the lives of those not involved in politics, military affairs, and the relations between states. And even then historians’ return to the inspiration of Herodotus was relatively brief. The nineteenth-century German scholars who laid the foundations for history’s emergence as a subject of professional training and research kept history focused on those same Thucydidean subjects, from which it would not veer strongly again until the second half of the twentieth century. Thus this “first revisionist historian,” by the power of his words and arguments, forced all historians who subsequently differed from him to take up their own “revisionist” approaches. From then on, every historical interpretation that significantly and clearly differed from interpretations offered earlier could validly be termed a revision of others that had preceded it.

Of course, the term revisionist is anachronistic when applied to a work of ancient creation; it is a word of the late nineteenth century, not of distant coinage. Yet applying the term to the intellectual and methodological space that Thucydides put between himself and Herodotus offers us the chance to understand what, even long ago, historians were up to and always since have been. To do so, we have to give up many of the notions that we may have absorbed in early life. Then we are taught, often unintentionally, to think of historians as people who relate the facts of the past and little else—as people who teach us what feudalism was, when the Declaration of Independence was released, what caused the French Revolution, and how the Great Depression unrolled—and who then leave it at that. History thus becomes, and we too often incorrectly think of it as, a parade of facts—lists of events recorded just because they happened. But a mere relation of facts is not history.

History is what emerges from chronicle—when facts are used for a purpose. Herodotus’ Histories and Thucydides’ Peloponnesian Wars transcended chronicle and became history because their authors tried to explain the causes and outcomes of the wars of which they wrote, because they were linking events, acts, and motives causally and for a purpose.

From The Ever-Changing Past: Why All History Is Revisionist History by James M. Banner Jr., published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2021 by James M. Banner Jr. All rights reserved.