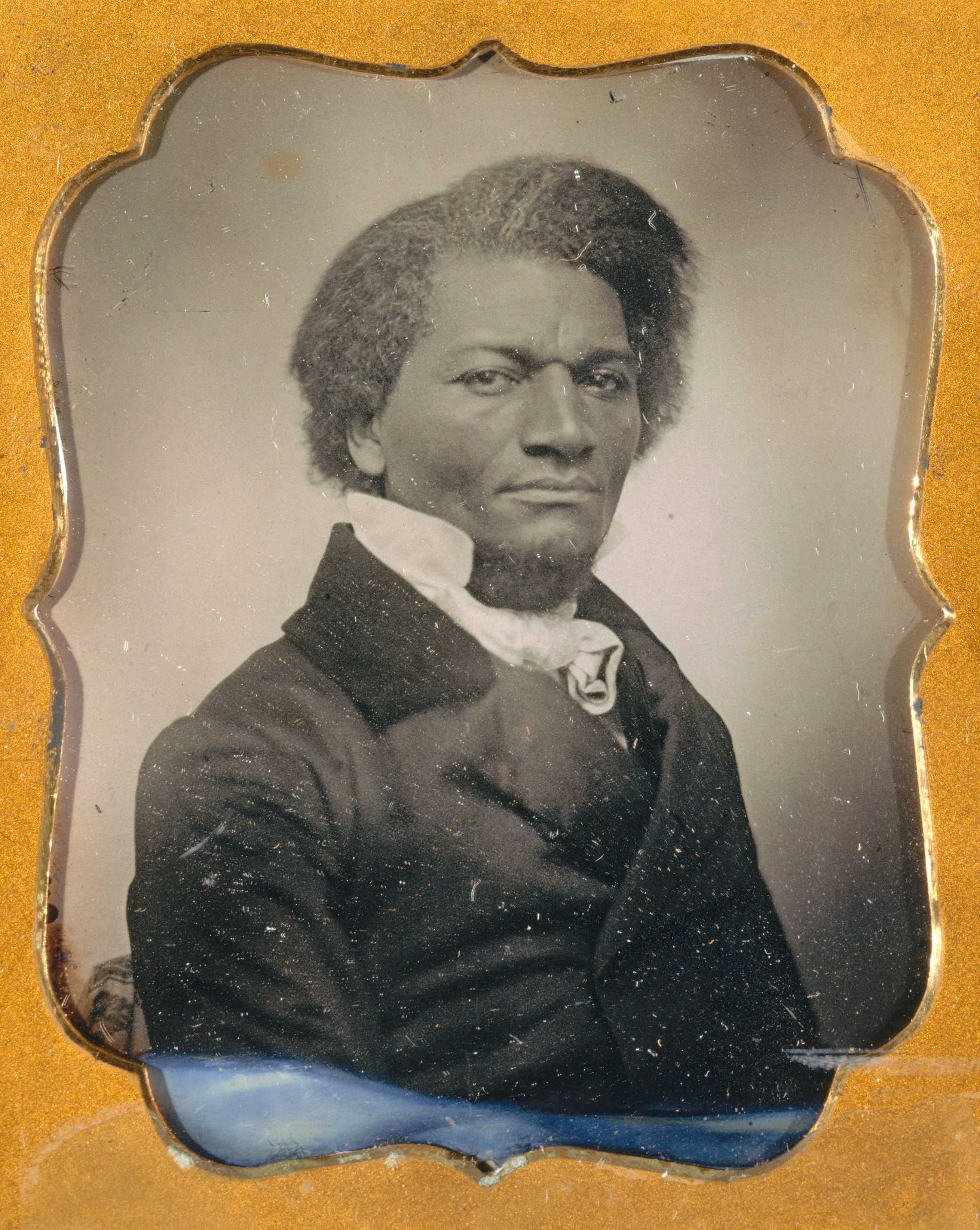

Frederick Douglass, c. 1855. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Rubel Collection, Gift of William Rubel, 2001.

Frederick Douglass, George L. Ruffin wrote in his introduction to the orator and abolitionist’s third biography, “seems to have realized the fact that to one who is anxious to become educated and is really in earnest, it is not positively necessary to go to college, and that information may be had outside of college walks; books may be obtained and read elsewhere.” Douglass, he added, “never made the mistake (a common one) of considering that his education was finished. He has continued to study, he studies now, and is a growing man, and at this present moment he is a stronger man intellectually than ever before.”

Below is a list of books and authors that he mentioned most during his lifelong education.

The Columbian Orator

The story of how Frederick Douglass learned to read is one of the most memorable in his Narrative of the Life, a crucial moment upon which the narrative’s existence depends. “The plan which I adopted, and the one by which I was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street,” he begins. “As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers.” These boys lived on Philpot Street in Baltimore, not far from a shipyard, and Douglass gave them bread in exchange for words. With this gift, he lingered on one book in particular.

I was now about twelve years old, and the thought of being a slave for life began to bear heavily upon my heart. Just about this time, I got hold of a book entitled The Columbian Orator. Every opportunity I got, I used to read this book.

He paid fifty cents—money he had saved from polishing boots—for it at a local bookstore. Dickson J. Preston calls it “possibly the best investment of his life” in his book Young Frederick Douglass.

The subtitle of the book reads, “A Variety of Original and Selected Pieces; Together with Rules; Calculated to Improve Youth and Others in the Ornamental and Useful Art of Eloquence.” The textbook’s author, Caleb Bingham, included speeches from George Washington, Socrates, Benjamin Franklin, and Cato, sometimes in rhetoric wholly imagined by Bingham, designed to showcase what he believed to be the most elevated forms of oratory, or what Douglass later called “eloquent orations and spicy dialogues denouncing oppression and slavery—telling what had been dared, done, and suffered by men, to obtain the inestimable boon of liberty.” The book began with a guide to how to become an effective orator, including advice such as “All exclamations should be violent. When we address inanimate things, the voice should be higher than when animated beings; and appeals to Heaven must be made in a loftier tone than those to men.”

“These were choice documents to me,” Douglass wrote of these speeches.

I read them over and over again with unabated interest. They gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul, which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance. The moral which I gained from the dialogue was the power of truth over the conscience of even a slaveholder. What I got from Sheridan was a bold denunciation of slavery, and a powerful vindication of human rights. The reading of these documents enabled me to utter my thoughts, and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery; but while they relieved me of one difficulty, they brought on another even more painful than the one of which I was relieved. The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers. I could regard them in no other light than a band of successful robbers, who had left their homes, and gone to Africa, and stolen us from our homes, and in a strange land reduced us to slavery. I loathed them as being the meanest as well as the most wicked of men.

“The appeal of Bingham’s Orator is not immediately obvious to the modern reader,” Granville Ganter wrote in the 1997 issue of New England Quarterly.

The Orator seems a rather unremarkable vehicle of piety, patriotism, and enlightened republicanism. Even its strong antislavery sentiments can be found in other English and American schoolbooks composed prior to 1820. But with 200,000 copies sold by 1832, Bingham's Columbian Orator was a standard, and widely imitated, text in American secondary school education from the late 1790s to 1820. Because a number of other texts were patterned on the Columbian Orator, it has been treated as a typical educational anthology for its era, but by encouraging generations of American students, including not only Douglass but Ralph Waldo Emerson and Harriet Beecher Stowe, to speak and write in a tradition of nonconformist activism, it had a power uniquely its own.

Ganter goes on to call the Orator a “radical text…not because it calls for changes in social relations beyond the terms set by the American Revolution; rather, it strives to conserve the volatile aspects of Revolutionary ideology most authors of American (and British) textbooks were carefully attempting to subdue.” Preston notes that he can hear the influence of Bingham throughout Douglass’ own speeches.

The Bible

Douglass’ first brush with reading happened earlier, when his owner’s wife read aloud from the Bible. He recounts in My Bondage and My Freedom, his second autobiography:

The frequent hearing of my mistress reading the Bible—for she often read aloud when her husband was absent—soon awakened my curiosity in respect to this mystery of reading, and roused in me the desire to learn. Having no fear of my kind mistress before my eyes (she had then given me no reason to fear), I frankly asked her to teach me to read; and, without hesitation, the dear woman began the task, and very soon, by her assistance, I was master of the alphabet, and could spell words of three or four letters. My mistress seemed almost as proud of my progress as if I had been her own child; and, supposing that her husband would be as well pleased, she made no secret of what she was doing for me. Indeed, she exultingly told him of the aptness of her pupil, of her intention to persevere in teaching me, and of the duty which she felt it to teach me at least to read the Bible.

Mr. Auld quickly stopped these lessons.

“If you learn him now to read, he’ll want to know how to write; and, this accomplished, he’ll be running away with himself.” Such was the tenor of Master Hugh’s oracular exposition of the true philosophy of training a human chattel; and it must be confessed that he very clearly comprehended the nature and the requirements of the relation of master and slave. His discourse was the first decidedly antislavery lecture to which it had been my lot to listen. Mrs. Auld evidently felt the force of his remarks; and, like an obedient wife, began to shape her course in the direction indicated by her husband. The effect of his words, on me, was neither slight nor transitory. His iron sentences—cold and harsh—sunk deep into my heart, and stirred up not only my feelings into a sort of rebellion, but awakened within me a slumbering train of vital thought. It was a new and special revelation, dispelling a painful mystery, against which my youthful understanding had struggled, and struggled in vain, to wit: the white man's power to perpetuate the enslavement of the black man. “Very well,” thought I; “knowledge unfits a child to be a slave.” I instinctively assented to the proposition; and from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery to freedom. This was just what I needed; and I got it at a time, and from a source, whence I least expected it. I was saddened at the thought of losing the assistance of my kind mistress; but the information, so instantly derived, to some extent compensated me for the loss I had sustained in this direction. Wise as Mr. Auld was, he evidently underrated my comprehension, and had little idea of the use to which I was capable of putting the impressive lesson he was giving to his wife.

The Liberator

After Douglass was free and married, he moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he changed his last name from Bailey to Douglass—borrowing the name of a character from Sir Walter Scott’s “The Lady of the Lake.” When he finally had enough money to do so, Douglass subscribed to the Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp’s abolitionist newspaper. “The paper came,” he describes in his Narrative, “and I read it from week to week with such feelings as it would be quite idle for me to attempt to describe. The paper became my meat and my drink.”

My soul was set all on fire. Its sympathy for my brethren in bonds—its scathing denunciations of slaveholders—its faithful exposures of slavery—and its powerful attacks upon the upholders of the institution—sent a thrill of joy through my soul, such as I had never felt before! I had not long been a reader of the Liberator before I got a pretty correct idea of the principles, measures, and spirit of the antislavery reform. I took right hold of the cause. I could do but little; but what I could, I did with a joyful heart, and never felt happier than when in an antislavery meeting.

Douglass had already been studying the nuts and bolts of oratory, and now he was learning the language of the antislavery movement, the words that he would be able to temper and cast into adamantine speeches. Not long after he started reading the Liberator, Douglass started his own abolitionist newspaper based in Rochester, The North Star.

Charles Dickens

From April 1852 through the end of 1853, Frederick Douglass’ Paper—the future name of the North Star—published all of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House in serialized installments.

In her book Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies, Elizabeth McHenry writes,

Douglass promoted the publication of Bleak House as a significant event, supplying his readers with the supplemental texts, including biographical sketches of Dickens and notices informing readers of the record-breaking sales of his work abroad, that were traditionally employed by newspaper editors to stimulate and maintain their readers’ interest in serialized fiction. Nevertheless, during the eighteen-month serialization of Bleak House in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, the main literary attraction of the newspaper was not Dickens’ novel but, rather, critical discussion of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin…The one exception to the weekly inclusion of Bleak House in Frederick Douglass’ Paper points to the literary and political priorities of Douglass’ readers: on 1 October 1852 an editorial decision to reprint the text of Charles Sumner’s speech addressing his motion to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act left no room for the weekly installment of the novel.

McHenry goes on to argue that

Douglass was intent on laying the work of European, American, and African American writers side by side in Frederick Douglass’ Paper. His purpose in doing so was to prove by association that this writing was equal and to insist, at the same time, that literary talent was transracial. In the juxtaposition of all of this literature—fiction about legal injustice in Bleak House, fiction about racial injustice in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and nonfiction about slave experience in the slave narratives—the newspaper’s readers were able to see them as connected by theme (injustice) and in political intent (to reform the justice system, abolish slavery).

When describing the torture used to “keep the slave in his condition as a slave in the United States” in My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass adds, “If anyone has a doubt upon this point, I would ask him to read the chapter on slavery in Dickens’ Notes on America. If any man has a doubt upon it, I have here the ‘testimony of a thousand witnesses,’ which I can give at any length, all going to prove the truth of my statement.”

William Shakespeare

On July 5, 1852, Douglass gave his famous Fourth of July speech. In it, he references the Bible and Shakespeare, two companions who followed him into many an address. At one point, he borrows a line from Marc Antony’s “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears” soliloquy: “The evil that men do lives after them / The good is oft interred with their bones.” Later in the speech, he counters anyone who would claim that the Constitution sanctions slavery by quoting Macbeth:

Then, I dare to affirm, notwithstanding all I have said before, your fathers stooped, basely stooped

To palter with us in a double sense:

And keep the word of promise to the ear,

But break it to the heart.

And instead of being the honest men I have before declared them to be, they were the veriest imposters that ever practiced on mankind. This is the inevitable conclusion, and from it there is no escape. But I differ from those who charge this baseness on the framers of the Constitution of the United States. It is a slander upon their memory, at least, so I believe.

A list of the books in his Washington, DC, home show how often Douglass must have consulted the playwright: not only did he have the complete works of Shakespeare, he also owned many works of scholarship on Shakespeare. Also well represented in his library were Thomas Carlyle, Tennyson, Thackeray, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and any book about Abraham Lincoln.

Suffragettes

Frederick Douglass attended the 1848 women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, and in his third biography he sets aside space to

make some more emphatic mention than I have yet done, of the honorable women who have not only assisted me but who, according to their opportunity and ability, have generously contributed to the abolition of slavery, and the recognition of the equal manhood of the colored race. When the true history of the antislavery cause shall be written, women will occupy a large space in its pages; for the cause of the slave has been peculiarly woman’s cause.

(Of course, when the vote for women failed to arrive, decade after decade, some of the suffragists Douglass knew sank to supporting white supremacy.) He thanks Lucretia Mott and the Grimkés, Lucy Stone, and a parade of other women. He mentions a book written by Susan B. Anthony and Stanton, The History of Woman Suffrage, as well as the “gifted authoress of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe. Happy woman must she be that to her was given the power in such unstinted measure to touch and move the popular heart!”

Elsewhere on his bookshelves you can find slave narratives from Sojourner Truth and Harriet Jacobs.

Robert Burns

Frederick Douglass was in the middle of his grand tour around Europe when he arrived in Ayr, Scotland, in April 1846. He wrote to abolitionist Abigail Mott,

It is famous for being the birthplace of Robert Burns, the poet, by whose brilliant genius every stream, hill, glen, and valley in the neighborhood have been made classic. I have felt more interest in visiting this place than any other in Scotland, for, as you are aware (painfully perhaps), I am an enthusiastic admirer of Robt. Burns.

His trip had made him an even bigger fan of the poet.

I have ever esteemed Robert Burns a true soul, but never could I have had the high opinion of the man or his genius, which I now entertain, without my present knowledge of the country to which he belonged—the times in which he lived, and the broad Scotch tongue in which he wrote. Burns lived in the midst of a bigoted and besotted clergy—a pious, but corrupt generation—a proud, ambitious, and contemptuous aristocracy, who, esteemed a little more than a man, and looked upon the ploughman, such as was the noble Burns, as being little better than a brute. He became disgusted with the pious frauds, indignant at the bigotry, filled with contempt for the hollow pretensions set up by the shallow-brained aristocracy. He broke loose from the moorings which society had thrown around him. Spurning all restraint, he sought a path for his feet, and, like all bold pioneers, he made crooked paths. We may lament it, we may weep over it, but in the language of another, we shall lament and weep with him. The elements of character which urged him on are in us all, and influencing our conduct every day of our lives. We may pity him but we can’t despise him. We may condemn his faults, but only as we condemn our own. His very weakness was an index of his strength. Full of faults of a grievous nature, yet far more faultless than many who have come down to us on the page of history as saints.

He ended by asking his friend to “read his poems, and, as I know you are no admirer of Burns, read it to gratify your friend Frederick.”

For a look at other educations obtained elsewhere, see the other entries in our reading list series: Julia Ward Howe, Walt Whitman, Willa Cather, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Theodore Roosevelt, Nella Larsen, Flannery O’Connor, and Emily Dickinson.