History does not reach us only in classrooms and via textbooks; movies, novels, songs, and even video games have shaped how we understand what came before the present for generations. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring the history and allure of pop culture’s period pieces, artifacts that captivated audiences with their conceptions of the past—and the political and cultural contexts that made these historical fictions so compelling.

In 1941 Douglas Fairbanks Jr. arrived in Buenos Aires to spread goodwill in the name of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The State Department sponsored the trip; U.S. officials feared that Latin America, and Argentina in particular, might be edging closer to the Axis. The Hollywood star’s visit did little to help the cause, and Fairbanks’ diplomatic blunders angered many. Though nominally a “goodwill trip,” the Argentine media suspected him of gathering intelligence for the U.S. government on fascist sympathies in Argentina, leading to much mockery, particularly by the right-wing press. Time magazine reported that when a firecracker went off near Fairbanks, his outsize reaction produced local headlines such as hero of a hundred films almost dies of fright. Variety presented Fairbanks’ mission as a success but conspicuously reported that actors would no longer be sent to Latin America on “official” State Department business.

Fairbanks Jr. was a star in his own right, but his father, Douglas Fairbanks Sr., had been a leading icon of silent film. The elder Fairbanks’ movies—particularly those he made at the height of his fame in the mid-1920s, including 1924’s The Thief of Bagdad and 1922’s Robin Hood—had raised the bar for set design, budget, and action choreography in film. After his greatest box-office success, The Black Pirate (1926), Fairbanks Sr. wrote and starred in The Gaucho, his penultimate silent film, a year later.

The Gaucho is a retelling of the Robin Hood story providing both racial and religious uplift: the protagonist goes from being a violent foreign outlaw to a familiar romantic hero. As the charismatic leader of an outlaw band of gauchos, Fairbanks’ nameless protagonist must, contrary to his own selfish beliefs, save an Andean city from the cruel General Ruiz with the help of a mountain girl played by then-unknown Mexican actress Lupe Vélez. Still hesitant to risk his own life to help others, he stops at the city’s shrine after being infected with the plague spreading across the city; a religious epiphany cures the infection and inspires him to fight for his new home. At the movie’s end, having defeated Ruiz and vanquished the plague—which was merely a symbol of the city’s spiritual corruption—he triumphantly marries Vélez’s character.

Fairbanks’ choice of an Argentine setting was somewhat accidental. He had picked up the idea at a Catholic shrine in Lourdes—the site of Saint Bernadette’s visions of the Virgin Mary—where he had traveled with his wife, actress Mary Pickford, in search of a miracle cure for his mother-in-law’s breast cancer. Domestic troubles may have led Fairbanks to seek a “darker” atmosphere compared to his prior films. Argentina fit the bill perfectly, exotic and mysteriously South American yet with a literary tradition—the gauchesca—whose protagonist loosely resembled the American cowboy.

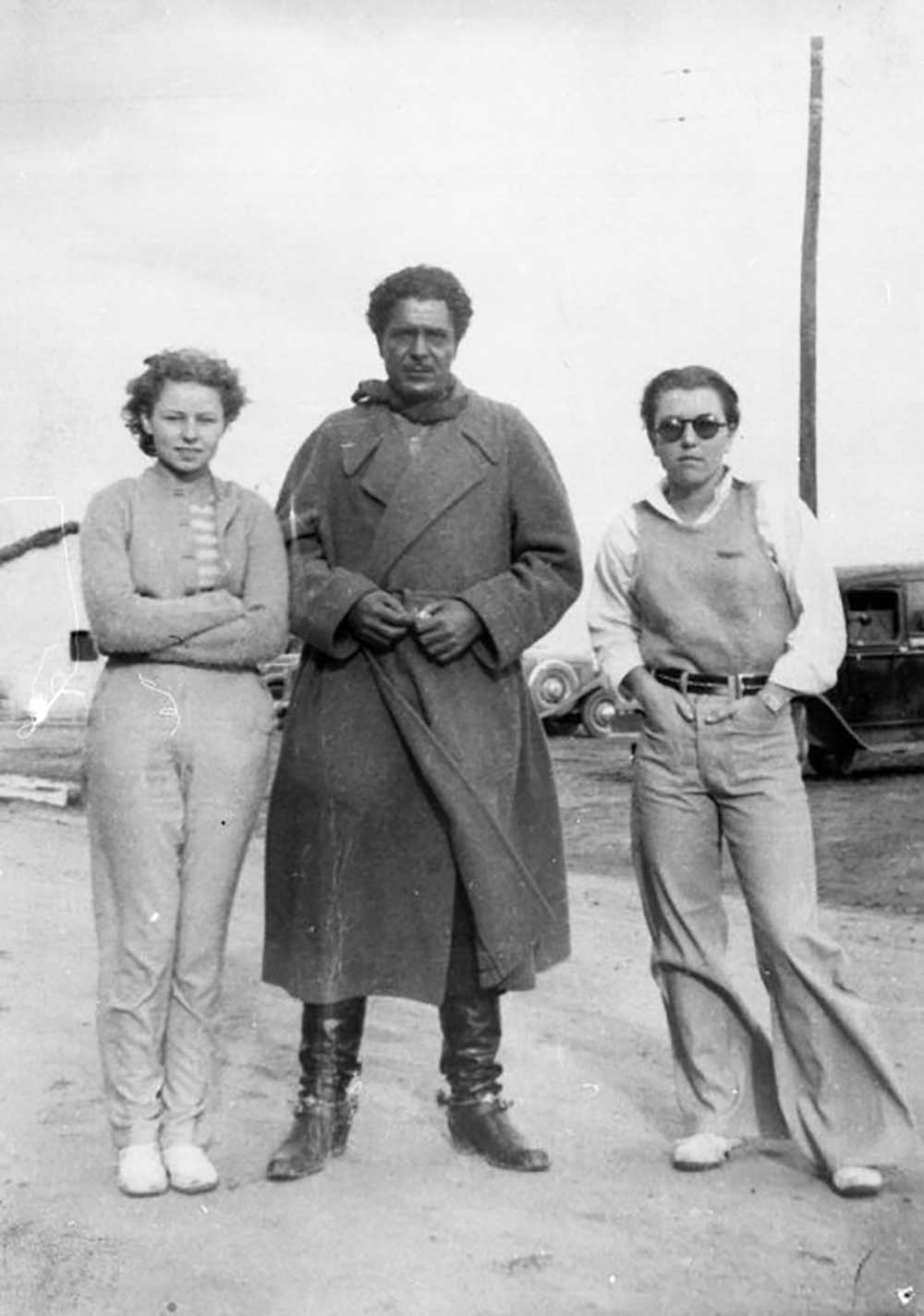

Roughly a hundred gauchos accompanied and served Fairbanks’ character in the film, fighting alongside him and helping him during his early outlaw days. The gauchos’ authenticity was much touted in promotional materials, even though the film was shot in its entirety at the United Artist Studios in Hollywood, the actors were Mexican, and the cow herders they played spend the story far from any cows. Offscreen, gauchos are best understood as free-roaming, independent ranchers for hire who trawled much of what is now central Argentina during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. But Fairbanks told the Los Angeles Record that he intended to show “the South Americans as we think of them rather than as they are.”

The filmmaker was something of a pioneer, originating what became an important subgenre of the 1930s and 1940s, the gaucho Western. Carmen Miranda, Rita Hayworth, Rudolph Valentino, Fred Astaire, Betty Grable, Maureen O’Hara, Lupe Vélez, and Fairbanks all starred in gaucho Westerns at crucial points in their careers. So did Mickey Mouse, whose second-ever appearance, The Gallopin’ Gaucho, was meant as a spoof of Fairbanks’ blockbuster. Mashing together Latin American stereotypes into an easily digestible mishmash, the gaucho Western featured bizarre depictions of Argentina and its people as a land of swashbuckling romancers and moronic yet noble-hearted cowhands. The white American characters, meanwhile, always proved to be earnest, sophisticated agents of good. These rehearsed and extended caricatures and oversimplifications helped solidify an “Argentina” of the prewar U.S. imaginary, and all the U.S. parties involved—audiences, studio executives, actors, directors, and state officials—could watch and feel the heft of their own benevolence toward poor Argentina.

Partly because of where the film industry settled—California, manifest destiny’s manifest destiny—the production of Westerns accelerated at a frenzied pace in cinema’s early years, and the genre’s popularity proved lasting enough to spin off variants, such as the gaucho Western. Thirty or so gaucho Westerns were produced over about twenty-five years—modest compared to Hollywood’s typical onslaught but no mere blip. When Douglas Fairbanks introduced the gaucho into the U.S. mass cultural landscape in 1927, the character’s fate became permanently linked to the cowboy’s. Each was the foundational archetype of its respective liberal federal republic during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Gauchos’ efforts to resist conscription are in many ways the central drama of the gauchesca, the genre that gave gauchos’ adventures literary form in Argentina. During the nineteenth century, gauchos lived as freelance cattle ranchers, armed men who worked for large landowners and occasionally found themselves conscripted into small militias by caudillos, regional military leaders akin to warlords. Gauchos were rural Argentina’s army and workforce, with a reputation for heavy drinking, music playing, oral poetry, and troubled relations with the law. Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, Argentina’s newly established state sought to modernize the country. The gaucho was seen as an atavistic figure who had to be disciplined via forced incorporation into a nascent national military. In those same years, the Argentine state attempted to exterminate the Indigenous occupants of what is now its central and southern territory, leaving tens of thousands dead and many more landless and destitute.

Many gauchos assimilated as their traditional lifestyle became increasingly criminalized. Others became thieves and bandits out of desperation and roamed the countryside preying on the weak and careless. Argentina was a “modern” country now, and gauchos couldn’t be allowed to run amok as before. At the same time, waves of European immigration motivated the government to develop a more cohesive national mythology that could subsume their various traditions—Spanish, Italian, German, Jewish—to the singular Argentine banner. The political and cultural elites who had pushed to end the gauchos’ way of life through conscription and assimilation went on to enshrine them as the nation’s ideal in literature and the arts, a potent symbol of the post-independence national character, as critic Josefina Ludmer notes in her defining 1988 study of gauchesca, The Gaucho Genre: A Treatise on the Motherland.

Facundo, an 1845 novel and treatise by future Argentine president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, constructs an early typology of the gaucho while advocating for his elimination. Framed as a loosely factual biography of the caudillo Facundo Quiroga, Sarmiento’s masterpiece is considered the founding gauchesca text. The greatest and most celebrated of the gaucho stories written in the late nineteenth century was José Hernández’s epic poem Martín Fierro, published in two parts, the first in 1872 and the second in 1879. As Argentina’s national identity solidified, Martín Fierro was quickly canonized as the country’s epic.

Argentina’s landscape was also part of the gaucho archetype. Like the Wild West, city dwellers saw the Pampas as a land of wilderness, opportunity, and conflict inhabited by pathbreaking colonists, many of them recent immigrants. The Pampas became a literary trope just as gauchos’ lifestyle was being extinguished. Any freedom its open plains once harbored was now curtailed, its land partitioned and plotted for exploitation much like the American West. Both utopias could serve only as the myths they always were.

How the gaucho arrived in the U.S. is hard to say. Facundo was translated into English in 1861, relatively soon after its initial publication, and its translator, Mary Mann; her husband, Horace; and their intellectual New England circle (among them Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) tried to publicize it. Mary Mann hoped that her translation would further her friend Sarmiento’s ambitions for the Argentine presidency by strengthening his visibility in the U.S., a major asset for any Latin American politician. Critics welcomed Facundo warmly, though its influence did not reach much beyond the Manns’ group of friends.

Martín Fierro wasn’t published in English in the U.S. until 1935, with broader distribution the following year. The critic Percy Hutchison’s New York Times review featured an array of comparisons to cowboys and, though positive, complaints about the dearth of love songs and womanizing, “especially in view of the Latin temperament and the ever-present guitar.” Given that several gaucho Westerns were produced during the mid-1930s, U.S. publication of a defining gauchesca text at that time isn’t surprising, nor are Hutchison’s criticisms. As tends to happen with most translated books in the U.S., Martín Fierro wasn’t a best seller. Whether the writers, directors, and studio executives propelling the gaucho Western read it is largely unknowable.

Many tropes of the standard cowboy story, from the desert landscape to its racialized, mostly Indigenous antagonists and ubiquitous damsels in distress, appear in gaucho Westerns, questionably relocated farther south. Taverns become pulperías, lassos become boleadoras, damsels became señoritas, and cowboys acquire goofy “Hispanic” accents.

Before the 1920s, violent Mexicans set on kidnapping white damsels were the defining antagonists of Westerns, most famously in D.W. Griffith’s early work. Such representations thinned out in the late 1910s, after the Mexican government threatened to boycott U.S. cinema unless onscreen images of Mexicans improved. So Argentina substituted for Mexico on film, as did Brazil, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. The phony accents, costumes, and tropes used for one morphed into the others, diversified but no less stereotypical.

Captain Álvarez, released by the prolific silent-film studio Vitagraph in 1914, was a key predecessor of the gaucho Western. In that early film, U.S. nationals traveling in Argentina during the nineteenth century encounter warring factions of gauchos. They meddle, find love, kill some locals, and return home.

Another gaucho precursor appears in the 1921 film adaptation of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Vicente Blasco Ibañez’s 1916 best seller. Directed by Rex Ingram, it is widely regarded as one of the first antiwar films. A family drama, it tells of a Spanish patriarch by the name of Madariaga living in Argentina who has two daughters, one married to Marcelo, a Frenchman Madariaga favors over his other son-in-law, the German Karl. Rudolph Valentino, then a complete unknown, played the favorite grandchild, with whom Madariaga travels to the poor immigrant neighborhood of La Boca, in southern Buenos Aires, where gauchos like them supposedly do the tango. They seduce barmaids and drink heavily, as if they were nomadic, rural working-class men and not aristocratic European proprietors of an estate who were more likely to write about gauchos than mingle with any. The film’s logic borrows gaucho identity superficially, transforming it into a disguise that anyone with a remote connection to the Pampas could wear.

Ingram’s epic became the highest-grossing film of the year, beating out Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid and shooting Valentino into stardom as the quintessential Latin lover. Studios took notice of the gaucho’s star- and hit-making potential, and many more films set in Argentina soon followed, including the 1935 film Under the Pampas Moon, in which the hard-riding gaucho Cesar Campo, played by Warner Baxter, finds a downed plane in the Pampas. One survivor, a French singer played by Ketti Gallian, drags Campo to Buenos Aires, where she tries to teach him manners in a peculiar retelling of Tarzan. These fictional gauchos’ allegiances remain unknown and their history abstract, props for the American and European characters.

In 1974 the scholar Allen L. Woll described the phenomenon of the “Good Neighbor film,” which arose in the mid- to late 1930s. The Good Neighbor Policy had guided the United States’ political relations with Latin America during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration and Hitler’s ascension to power. Latin America was known to harbor fascist leanings, particularly among aristocrats and military men, and Roosevelt sought to prevent Nazism’s spread in the region. The goal was to fashion the U.S. into a reliable, caring, and generous neighbor to Latin America, at least in appearance.

But Roosevelt had to overcome the distrust wrought by a century’s worth of wars and invasions (including a then-recent invasion of Panama). His program thus included a soft, “cultural” approach. Nelson Rockefeller, later an active participant in U.S. interventions in Latin America’s military coups and dictatorships throughout the 1970s, ran the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA). The State Department initiative was tasked with promoting benevolent U.S. representations of Latin America, specifically those that insisted on America’s commitment to the region. The idea was that both Americans and Latin Americans would see these films and feel that the U.S. was a benevolent presence in the region. Millionaire John Hay Whitney, the OCIAA’s head of film—known in the film industry for coproducing Gone with the Wind—launched a “Latin film” initiative, which helped bring the gaucho Western to maturity.

When Whitney met with the major studio heads, executives agreed to produce films that strengthened continental unity against fascism on patriotic grounds, yet their plots often featured weak and stupid locals rescued by vigorous Americans. Perhaps Rockefeller thought that the films affirmed the U.S. commitment to supporting Latin America, but most Latin Americans found them condescending and self-congratulatory, if not outright insulting. A screening of Argentine Nights, a 1940 musical featuring the Ritz brothers and Andrews sisters, nearly ended in a riot. The films confirmed the United States’ self-regard and its disregard for the concerns and opinions of actual Latin Americans.

Argentina remained neutral for most of World War II, partly because Germany and Italy were among its biggest buyers of agricultural products and partly due to a degree of support for Mussolini in particular and the Axis in general among the ruling classes. Until the very end—when Argentina declared war on the Axis less than two months before Germany’s surrender, after years of pressure from the U.S.—Argentine censors edited any U.S. movies with explicitly anti-Axis sentiments. The government blocked some films from release altogether, including Chaplin’s satirical 1941 picture The Great Dictator, which mocked both Mussolini and Hitler. Massive debate among critics and journalists ensued, and the film was banned and unbanned multiple times by various government bodies. The Great Dictator wouldn’t screen in Buenos Aires until May 1945, weeks after the fall of Berlin. Billy Wilder’s 1943 World War II film Five Graves to Cairo was never shown, nor was the 1943 Paramount adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s Spanish Civil War novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

After the government undermined the domestic release of foreign anti-Axis films, Hollywood began withholding film stock from Argentina’s own film industry, which had been experiencing a golden age, with a burgeoning studio system producing hits like the 1935 tango musical Soul of the Accordion and the 1930 drama Prisoners of the Land. Little evidence of widespread fascist sympathies among Argentine filmmakers exists, though historian Tamara Falicov argues that such leanings thrived in the government and military. Hollywood’s self-interest likely contributed to a decision that would hamper Argentine film production for years, as the relative scarcity of local films compelled theaters to show Hollywood movies. All of this came amid the wartime collapse of the European movie market, when Hollywood turned to underdeveloped markets for theater revenue.

As the Good Neighbor Policy swung into full effect during the 1930s, gaucho Westerns abounded, from 1933’s The Gay Gaucho and 1935’s Hi Gaucho! to 1940’s Down Argentine Way, which flung the Brazilian-Portuguese actress Carmen Miranda into global celebrity despite her confusingly tropical performance, a mishmash of Caribbean stereotypes that makes little sense even within the film. Gaucho Serenade and Argentine Nights both appeared in 1940. Law of the Pampas (1939) featured William Boyd as the cowboy detective par excellence, Hopalong Cassidy. In You Were Never Lovelier, a 1942 remake of an Argentine film, Fred Astaire and Rita Hayworth danced to music by Jerome Kern. Classic early Westerns such as Fairbanks’ gave way to musicals with massive casts and budgets, soundtracks by the Andrews Sisters, and dance routines by the Nicholas Brothers. The gaucho was no longer brooding and grim but cheerful and prone to dancing—suitable, U.S. filmmakers and politicians hoped, for the improvement of continental relations.

Among the many famous gaucho impersonators, Mickey Mouse stands out. The Gallopin’ Gaucho (1928) was a send-up of Fairbanks’ film, which had premiered the previous year to great success. The plot is simple: Mickey is a gaucho, riding his ñandú (ostrich) across the pampa until he comes to “Cantino Argentino,” a grammatically incorrect allusion to the pulperías where gauchos spent much of their time. He spots Minnie dancing to the tune of a Black man’s bass and joins her. Black Pete, a hairy primate coded as Black, cuts in, snatches Minnie from Mickey’s arms, and flees. Mickey gives chase and ultimately gets her back.

Disney returned to the continent in 1942 with Saludos Amigos, which became a well-known example of a Good Neighbor film. The anthology film featured cartoons set in Rio de Janeiro, in Santiago, and near Lake Titicaca, and one segment was titled “El Gaucho Goofy.” In 1972, during the brief presidency of socialist Salvador Allende, Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart published How to Read Donald Duck in Chile. Only a year later, after Augusto Pinochet took power in a U.S.-backed coup, copies were set on fire and dumped in the ocean. The book also faced difficulties in reaching readers in the U.S. thanks to Disney’s impounding of its entire first printing, though such maneuvers only cemented the book’s fame. Dorfman and Mattelart’s work analyzed how Disney cartoons functioned as imperialist corporate American propaganda in Latin America. The authors argued that Saludos Amigos; its successor, 1944’s Three Caballeros; and the universe of Disney cartoons that blossomed thereafter in Latin America made children “contribute to [their] own colonization,” as they imbibed depictions of themselves as inferior, backwards, and powerless.

With World War II over and television now sapping Hollywood’s domestic box office, international markets acquired new prominence; films about “exotic lands” intended for U.S. audiences were no longer as profitable. If Fox wanted to make a movie about gauchos, it would have to be shot in and sold from Argentina, which conveniently lowered production costs. Jacques Tourneur’s 1952 film The Way of a Gaucho, arguably the last gaucho Western, was one example. Based on American writer Herbert Childs’ 1948 novel—an adaptation of Martín Fierro inspired by his years in Argentina—it was shot on location and even featured Argentine actors and stunt coordinators, proudly announced by an title card at the start. The Argentine government supervised the script and shooting, which the film acknowledges in the form of gratitude to “the Argentine government.”

The Good Neighbor Policy ended promptly after the end of World War II. Communism and other strains of leftist activism acquired great force in Guatemala, Cuba, Brazil, Chile, and elsewhere, though the U.S. no longer tried to ingratiate itself with Latin Americans—it had learned its lesson and mostly stuck to training and arming soldiers and politicians. Argentina’s economic power declined over the second half of the twentieth century, further lessening the Pampas’ charm.

Rewritings and extensions of gauchesca literature emerged constantly in the next half century, most famously in Jorge Luis Borges’ stories “El Sur” and “Emma Sunz.” Gabriela Cabezón Cámara’s 2017 novel The Adventures of China Iron, which was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize, imagines the story of Martín Fierro from the perspective of his wife, whom Fierro leaves early on in Hernández’s poem, while Oscar Fariña’s El guacho Martín Fierro, also from 2017, rewrote the original in the slang of Argentina’s contemporary urban poor. The gaucho Western slid into ignominy, one among many of Hollywood’s never-ending novelties. Fairbanks’ career tanked soon after the release of The Gaucho and the emergence of talkies. In the United States gauchos are now mostly remembered, if ever, for Steely Dan’s best album and tan leather.

Read past entries in this series: Caroline Wazer on Assassin’s Creed, Kristen Martin on orphan trains, Dylan Byron on E.M. Forster’s Maurice, Jeremy Swist on heavy metal’s fascination with Roman emperors, and Emma Garman on James Fox’s White Mischief.