In the Loge (detail), by Mary Cassatt, 1878. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Hayden Collection—Charles Henry Hayden Fund.

When Maria Mitchell discovered a comet in 1847 at the age of twenty-nine, people began to spend as much time watching her as she spent watching the sky. Tourists visited the Nantucket Atheneum, where Mitchell was a librarian, just to see the astronomer at work. There was something so intoxicating about the scene that the gazer herself became a star. In 1854 Mitchell recounted the attention she received:

Four women have been delighted to make my acquaintance, three men have thought themselves in the presence of a superior being, one has offered me twenty cents because I reached him the key of the museum, one woman has opened a correspondence with me, and several have told me that they knew friends of mine. Two have spoken of me in small letters to small newspapers, one said he didn’t see me, and one said he did!

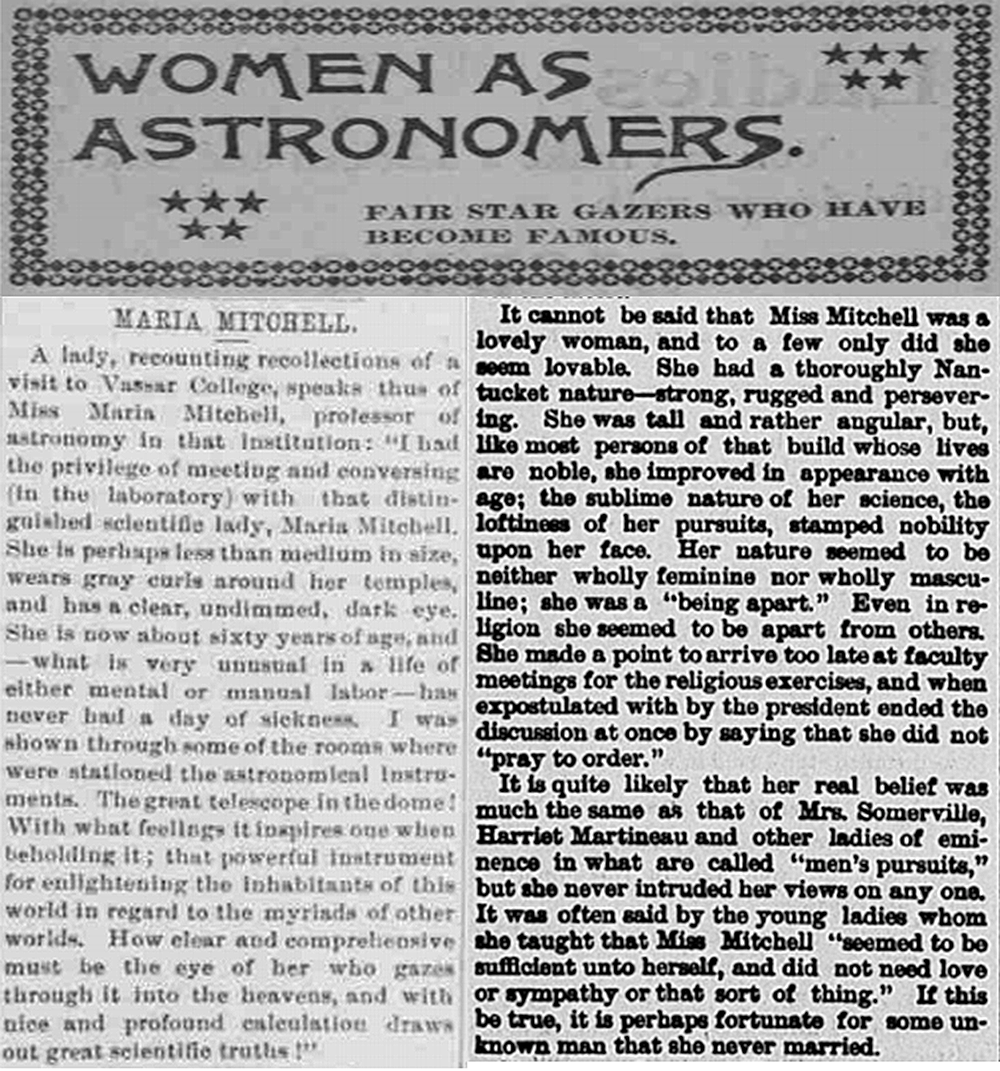

Fans wanted to see her up close, but part of what made them light up was her detachment. Embedded in the highest praises of her scientific work were reports of her aromantic identity and reputed aloofness and a belief that her scientific study left no room for a personal life. “It cannot be said that Miss Mitchell was a lovely woman, and to a few only did she seem lovable,” one writer in the Bismarck Tribune claimed after her death in 1889. “She was admired, highly respected, even reverenced; but she was not tenderly loved.”

Mitchell was not the antisocial, hermetic figure people envisioned her to be. At Vassar, where she became the first woman professor in the nation, she maintained an active public life and gained renown for the close relationships she built with students. The parties she threw for colleagues and pupils were famous. Mitchell was known to keep her observatory open for anyone to come visit at any time of the night.

As a trailblazer of sunspot photography and a specialist in the surface of Saturn and Jupiter, Mitchell was a technical master who also embraced the literary dimensions of astronomical study. Her invaluable journals are at times wild, always vivid, and filled with poems. In one poem, Mitchell rhapsodizes over the young students who have become an essential part of her emotional and intellectual life and future.

I think of the girls soon women to be

Who daily bring peace and joy to me

Who watch the Bear whirl round in his lair,

Who get up too soon to look at the moon

Who go somewhat mad on the last Pleiad

Who seek to try on the sword of Orion

Who, lifting their hearts to the heavenly blue,

Will do women’s work for the good and the true

And as sisters or daughters or mothers or wives

Will take the starlight into their lives.

“We especially need imagination in science. It is not all mathematics, nor logic, but it is somewhat beauty and poetry,” Mitchell wrote in her journal.

Public engagement was central to her life and work. Mitchell protested slavery, advocated for suffrage, and fought to cultivate the image of a woman scientist at a moment when institutions made sure she was invisible. A founding member of the Association for the Advancement of Women, she became its president in 1875 and continued to chair its science committee after her presidency. She was the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Mitchell did value one strain of the solitude attributed to her by popular media, firmly asserting her right not to marry. In a poem about a schoolteacher she wrote in the early 1840s, Mitchell praised the “spinster race / Who always fill the highest place / In seeking others good,” insisting she would remain single forever. Accounts of her celibacy and singlehood abounded in print media. They took the image of the “old maid” contemporaneously circulating in the short stories of Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mary Wilkins Freeman, and Sarah Orne Jewett and imbued it with dynamism. “Her hair is white, but her black eye sparkles with all the fire of youth,” one profiler wrote. “Intellectual people never grow old.”

Many newspapers and magazines celebrated Mitchell’s refusal to marry in the belief that her commitment to studying the sky transcended the need for a love life. Profiles of the astronomer endlessly detailed her nonexistent personal life. Popular Science Monthly described her habit of retreating to the sky during parties: “No matter how many guests there might be in the parlor, Miss Mitchell would slip out, don her regimentals, as she called them, and, lantern in hand, mount to the roof.”

“Her heart is in her science,” the Charlestown Enterprise claimed.

The girl astronomer lived a single life. In a confidential moment one day she confessed that it was much harder for girls to keep from being married than to marry, which is undoubtedly true. It requires far more heroism.

In this view, her commitment to the study of astronomy is a result of her heroic resistance to romance.

The fascination with Mitchell was part of a larger interest in the stories of so-called great women. Anthologies of biographical sketches—including Our Famous Women: An Authorized Record of the Lives and Deeds of Distinguished American Women of Our Times (1884) and Daughters of Genius: A Series of Authors, Artists, Reformers, and Heroines, Queens, Princesses, and Women of Society, Women Eccentric and Peculiar (1885), both of which include entries on Maria Mitchell—held up accomplished women like Clara Barton, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Elizabeth Stuart Phelps for readers to emulate.1

At the same moment, Americans were intrigued by the idea of the spinster, particularly in New England. In her book Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own, Kate Bolick names two factors in the rise of spinsters in postbellum New England beyond the deaths of millions of men in the Civil War: “the bruised postwar economy, which made it difficult for men to professionalize and marry early,” and “a regional commitment to intellectual and literary pursuits, which extended to women” and “created a social atmosphere in which single women were allowed, a little bit, to flourish.” When prominent mid-nineteenth-century women like Catharine Maria Sedgwick, Lucy Larcom, Frances Willard, and others who identified as reformers or professional writers remained single, popular opinion toward spinsterhood changed. Or at least it did toward a very particular kind of unmarried woman: the single, upper-middle-class white woman who devoted her life to a worthy cause, who traded matrimony for the pursuit of charity or intellectual study.

An article for the Sunday Oregonian on the merits of spinsterhood for women cites the example of “Miss Maria Mitchell’s single life” to prove that “a large part of the best work of the world is wrought by single women.” According to this logic, Mitchell is an ideal spinster, a high-minded woman who has given up a romantic life for an admirable reason—scientific study. The essential work of married women goes unreported while the work of single women is acknowledged only with the requisite emphasis on marital status.

The hyperbole of Mitchell’s asociality and privacy in these profiles comes out of a larger fantasy around the solitude of the skies, but it’s also how many great women were represented in nineteenth-century media in the United States. The figure of the woman genius was nearly always a desexualized lady of high deportment. While narratives about artists and professionals like Maria Mitchell, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Eliza Potter, and Fanny Fern granted women new agency, and new powers to shape culture, the women themselves remained subjects created by restrictive structures outside their control.

These profiles overstating Mitchell’s solitude and monomania have an eerie resemblance to fictional reimaginings of her, which similarly dramatized her fixation on the sky and her turn away from romance. In 1891 Herman Melville published “After the Pleasure Party,” a long poem about a woman who struggles with the sacrifice of erotic love that comes with her lifelong dedication to studying astronomy, based on Mitchell. Her gaze was so transfixing in the nineteenth-century imagination that it makes sense that Nathaniel Hawthorne, who traveled through Italy with Mitchell in 1858, reimagined her as Miriam, the painter in his novel The Marble Faun. He likens Miriam’s focus to that of “the woman’s eye, that has discovered a new star.”

In July 1857 Emerson’s United States Magazine reported that a group of Boston women who were fans of Maria Mitchell had started a fundraising campaign with the goal of collecting “three thousand dollars to purchase a telescope for this distinguished and truly noble woman, who has devoted herself with so much zeal to the pursuit of science.” The coverage paid off: the women gathered sufficient funds and purchased the telescope. Detailed accounts of the new instrument, gigantic compared to the two-inch telescope Mitchell had used to discover a comet ten years earlier, appeared in mainstream newspapers around the country. The New York Evening Post offered this description of the telescope’s ocular powers: “It is mounted equatorially, according to the German method, and furnished with graduated circles for the determination of the positions of the heavenly objects. The circle for measuring right ascensions is divided to single minutes, but by means of a vernier reads to five seconds of time.” That these popular reports of Mitchell’s famed telescope, intended for a general, nonspecialized readership, provide advanced technical information about the instrument shows the depth of the public’s fascination with Mitchell and her work. It wasn’t enough for people to know that she had gotten a telescope; they wanted to learn everything there was to know about the sophisticated piece of technology that they had helped buy.

The crowdfunded gift represented the confluence of public and private that characterized her career: the most important object in her private workspace was linked to the outside world and her celebrity in it.

In 1985 the ghost of Maria Mitchell met the spirit of Marilyn Monroe. The nineteenth-century astronomer had a lot to say to the twentieth-century starlet. She shared with Marilyn her thoughts on men—“What man on earth isn’t selfish?”—and she invited Marilyn to enjoy with her the pleasures of unmarried life: “I never married. / Come walk with me.” Carole Oles imagines this encounter in her poem “Maria Mitchell in the Great Beyond with Marilyn Monroe.” The poem is part of her collection Night Watches: Inventions on the Life of Maria Mitchell. The thirty-eight poems in the book re-create scenes from Mitchell’s life, including her 1847 discovery of the comet and her travels in Rome with Hawthorne, and envision what her ghost might be thinking and doing in the spirit world of 1985. It is not entirely bizarre to construct a connection between her and Marilyn Monroe, given that Mitchell’s own spinsterhood was as glamorized and admired as Monroe’s romantic life was a century later.

For all the playful anachronisms of her poems, Oles frames her collection with a nineteenth-century document: the 1884 profile of Mitchell in the Charlestown Enterprise claiming that her decision to live a “single life” is an act of “heroism.” By opening her book with this text, Oles places her own reflections on Mitchell in the same tradition of celebrating and mythologizing the astronomer’s life in late nineteenth-century print culture.

Fictional retellings of Mitchell’s life continue to appear, from Julie Hecht’s 1998 short story “The World of Ideas,” about a woman trying to live like Maria Mitchell, to Sena Jeter Naslund’s 1999 novel Ahab’s Wife: Or, the Star-Gazer and Amy Brill’s 2014 novel The Movement of Stars.

What these present-day meditations on Maria Mitchell share with nineteenth-century accounts of her life is the way they all have direct encounters with Mitchell through her absence: her perceived and literal distance allows these writers to imagine being close to her. “While writing I felt inhabited by Maria’s personality and ideas,” Oles writes in the foreword to Night Watches. Naslund claims a similar possession of Mitchell’s spirit. Ahab’s Wife: Or, the Star-Gazer tells the story of Una Spenser, Captain Ahab’s lover, and her life on Nantucket after her husband embarks on his whaling expedition. In Ahab’s absence, she starts a close friendship with Maria Mitchell. Naslund describes the joys of learning about Mitchell on a research trip to Nantucket:

The first time I stepped off the ferry onto Nantucket in the face of a wet January wind, I was looking for Ahab’s wife. Herman Melville scarcely had mentioned her in his classic whaling novel Moby Dick; I hoped my journey to the island would suggest something of her character. But the first person who seized my imagination was Maria Mitchell. Snug in my taxi on the way to my bed-and-breakfast, the woman driver proudly informed me that Nantucket was the home of Maria Mitchell and that she was the first person, male or female, to sight an unknown comet by exploring the heavens with a telescope.

I’d never heard of Maria, but the novel I intended to write had stargazing as a central image. Might this astronomer, whom I had stumbled upon as soon as I reached the island of Nantucket, serve as a model for my fictional stargazer?

This is not unlike the trip to Nantucket described by the 1881 New York Times writer relating his magical imaginative encounter with Mitchell:

Looking off on the water from my abode, which is in an elevated part of the town, on an evening soon after my arrival, and thence above to the sky, a grand sweeping view of which was obtainable, I saw the comet and called to mind the fact that Maria Mitchell, the Professor of Astronomy at Vassar College, was born and reared here. In her own time and in our time, to experience the spinster astronomer is to feel her take over your soul.

Last year marked Mitchell’s two hundredth birthday. The Maria Mitchell Association in Nantucket hosted a series of events to honor the bicentennial, including a comet-chasing party, a parade, a Women in Science symposium, a red-tie soirée, and the grand opening of a new lab and classroom in the Science Library at the Historic Mitchell Schoolhouse. The six-month-long celebration was a combination of intellect and razzle-dazzle, a mix of academic roundtables and nighttime parties befitting the woman whose commitment to a life of the mind Americans treated with the flash of Marilyn and Diana, Britney and Beyoncé.

The intimacy of connection is what unites all of these direct and indirect encounters. “I wish I could swap half my head for half yours,” one eager tourist told Mitchell at the Nantucket Athenaeum in 1855. Watching her at work would not suffice; he wanted to make her a part of him. His desire might have been echoed in Oles’ foreword to Night Watches: “I could say my intention in this book is to bring Maria Mitchell back alive to a contemporary audience. Though I would be pleased if that were the effect of these poems, it is not why I wrote them. I was drawn to Maria Mitchell by private imperatives seeking satisfactions all their own.” For her most fervid devotees, the woman who “was not tenderly loved” is the close companion she never imagined or styled herself to be. “The best that can be said of my life so far,” Mitchell wrote in her journal in September 1854, “is that it has been industrious, and the best that can be said of me is that I have not pretended to what I was not,” no matter what everyone else saw when they looked at a star.

1 Maria Mitchell could also be someone who was curious about the lovable nature of brilliance: “Yesterday,” she wrote in her journal on November 24, 1854, “James Freeman Clarke, the biographer of Margaret Fuller, came into the Atheneum. It was plain that he came to see me and not the institution…He rushed into talk at once, mostly on people, and asked me about my astronomical labors. As it was a kind of flattery, I repaid it in kind by asking him about Margaret Fuller. He said she did not strike anyone as a person of intellect or as a student, for all her faculties were kept so much abreast that none had prominence. I wanted to ask if she was a lovable person, but I did not think he would be an unbiased judge, she was so much attached to him.” ↩