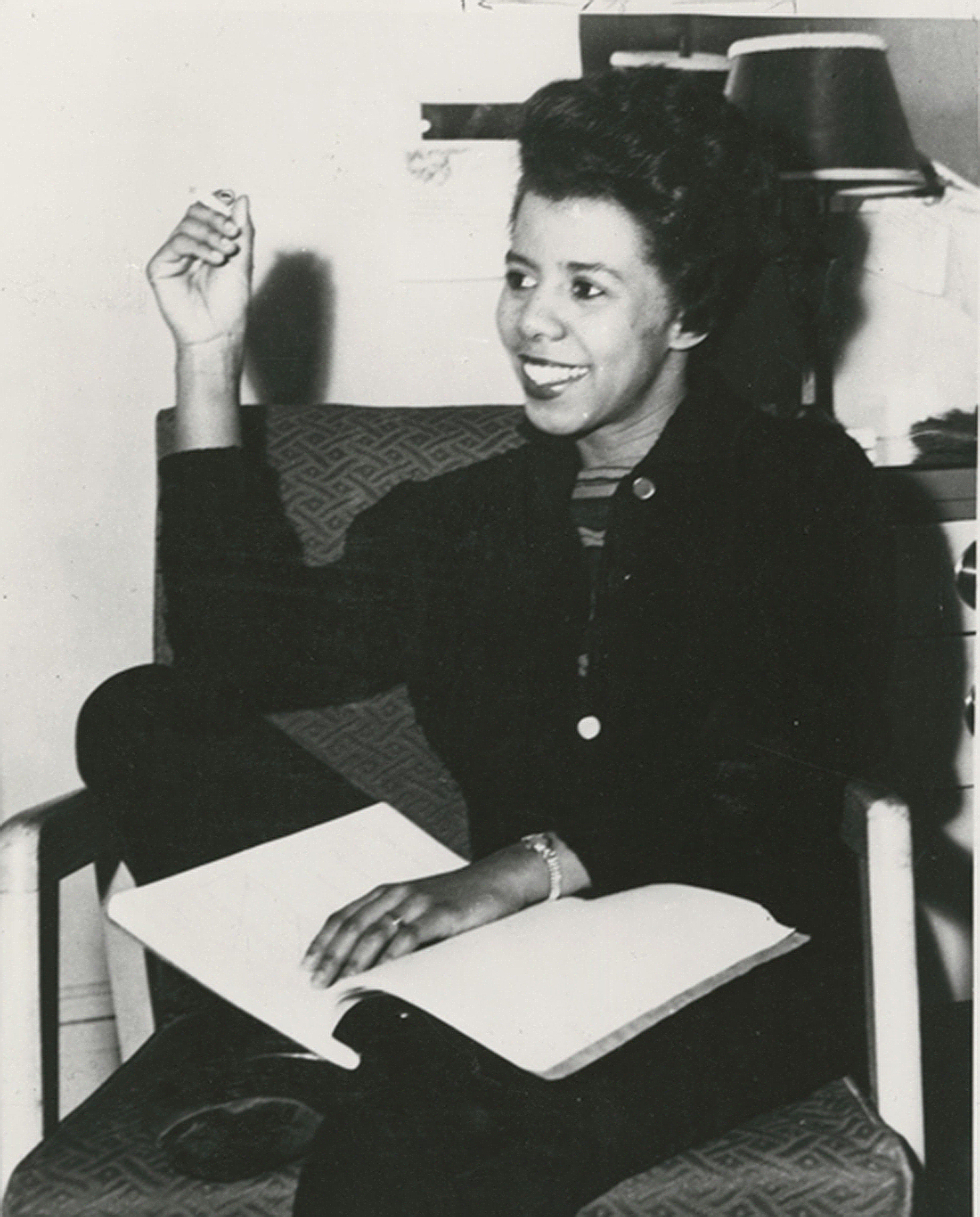

Lorraine Hansberry at the time of her play A Raisin in the Sun opening in New Haven, Connecticut, 1959. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Imani Perry, author of Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry, now available from Beacon Press.

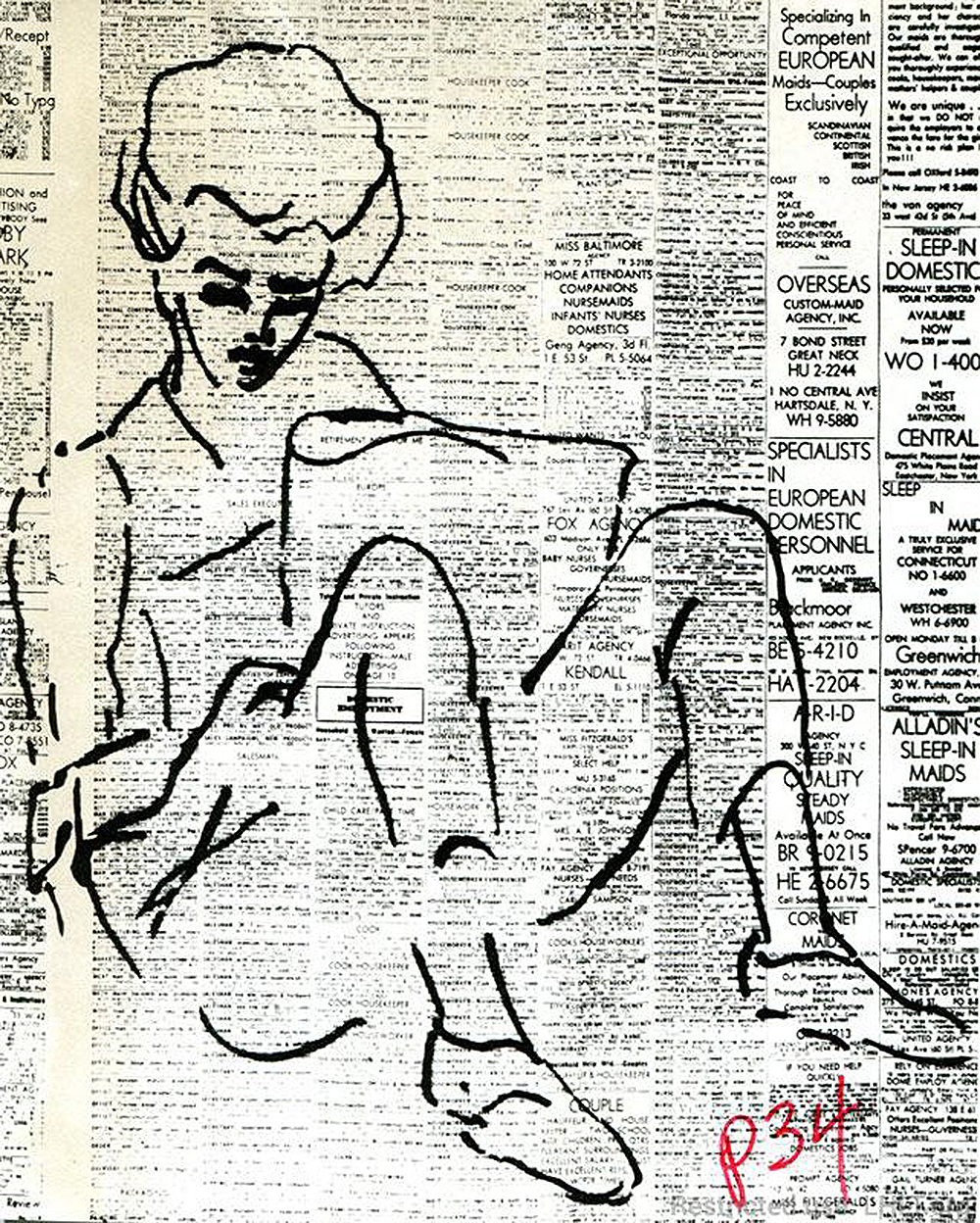

Even with a faint stink of vanity, self-portraits are appealing. Lorraine’s especially so. When she drew herself, she tended toward sparseness. A soft but angular form: she made her head oversize and always gave it a tilt or a bend. It is contemplation without arrogance.

Here she is in a reader’s pose: holding the paper, body hunched and folded into herself like a sullen teenager instead of a twentysomething playwright. Her choppy Italian haircut on straightened hair looks both rakish and puffy, as though she’d tried (and failed) to make a delicate African halo into something harder than it was. Lorraine is Puck or Peter Pan. Behind her, and filling her in, engulfing her, are words.

Lorraine Hansberry drew this self portrait on a newspaper page. On one of the back pages, after flipping past news of world leaders, famous actors, and global conflict. At her knees and feet are maid advertisements. And at the center of her form, in tiny words: “the domestic department.” Remarkable really. Like me, she was a woman of domestic stock. A brown body and Southern roots hold fast. Sitting in that crossroads space of gentility and backbreaking labor makes you say almost guiltily, “How did I ever get to be here?” writing and thinking for a living, and also ask, “How do I keep my spirit there?”

I think that’s why and how she wrote both Mrs. Youngers in A Raisin in the Sun: women who scrubbed other folks’ floors and washed other folks’ undergarments, whose knuckles burned with the bleach for another’s sanitation. And who still yearned.

If, as Lorraine’s friend James Baldwin said, we must treat identity as a loose garment, how ought we treat our embodiment? How should we draw it? Lorraine had an answer, let our forms become the frame of history, a portrait carved out of a billion facts and all their hauntings. Let us know the vastness that exists, inside and out, even when your reflection doesn’t shine back from the toilet bowl or a Broadway stage or a bestseller list. Personal, intimate, always incomplete, but fairly bursting with truth.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Ken Krimstein, The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth

• Katherine Benton-Cohen, historical adviser for the film Bisbee ’17

• Nicholas Smith, author of Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers

• Emily Ogden, author of Credulity: A Cultural History of U.S. Mesmerism

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing