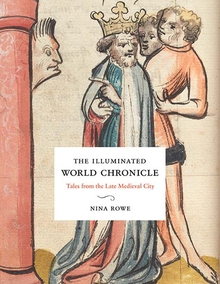

Nebuchadnezzar’s Idol with Musicians. The New York Public Library, Spencer Collection.

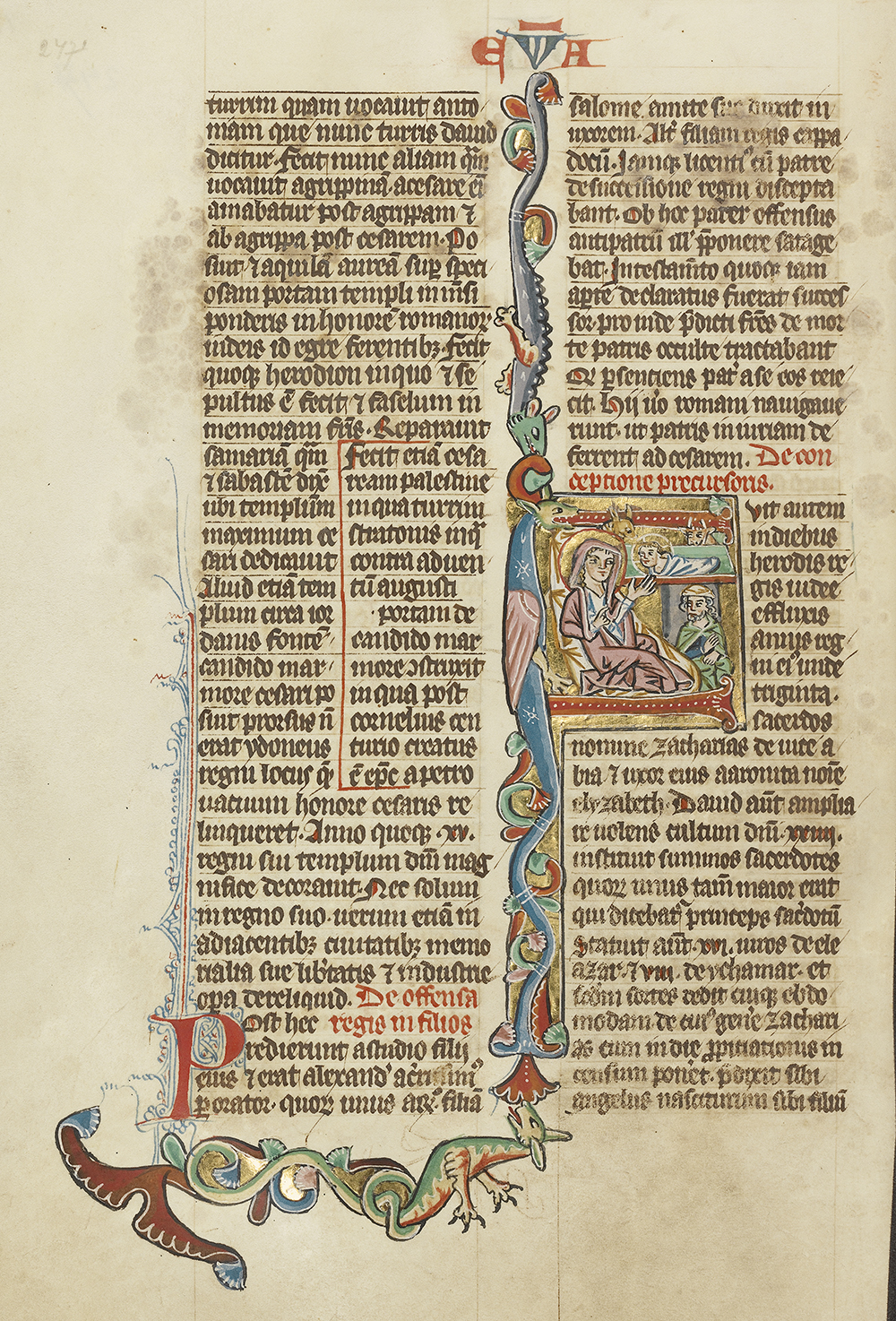

Illuminated Weltchroniken, or World Chronicles, were in vogue between roughly 1330 and 1430, and the bulk of the surviving fifty-six intact or reconstructible witnesses are localized to areas that correspond to modern Bavaria and Austria. In such works, biblical, ancient, and more recent imperial history, as well as mythological tales, are woven into a riveting, dialogue-rich, and sometimes playful narrative told in Middle High German verse. Images are integral to the genre, animating the tales with extensive pictorial cycles, usually of around 250 images dispersed over three hundred or so folios. The iconographies and styles of these illuminations range broadly, lacking rigidly circumscribed pictorial formulae. And there is no standardized World Chronicle text appearing in all manuscript witnesses.

With narratives describing events from the past and profuse illustration, illuminated Weltchroniken bring to mind other classes of illustrated books popular in northern Europe in the high and late Middle Ages, but they distinguish themselves in significant ways. Those familiar with the Grandes chroniques tradition might wonder if the corpus of illuminated Weltchroniken constitutes a Teutonic parallel to those French manuscripts, which recount royal history from the Merovingians through the Carolingians and Capetians and on to the Valois. Beyond the modern convention to characterize both book types as “chronicles,” however, there is little affinity between these families of manuscripts. In the first place, the German World Chronicle manuscripts are not chiefly concerned with political history, instead focusing on tales from scripture, beginning with Genesis and extending through the books of Kings, often with long interpolations on Greek gods and heroes, and with only select witnesses turning finally to Greco-Roman history and legends of the Holy Roman emperors. Moreover, while Grandes chroniques manuscripts functioned within larger campaigns aimed at securing the legitimacy of the Valois line, none of the illuminated Weltchroniken from the heyday of the genre appears to have been made for imperial or high princely audiences, and no coherent political agenda seems to have inspired the popularity of the works. One might further inquire about affinities between the circulation of Weltchroniken and the formulation of French vernacular prose histories at the beginning of the thirteenth century. Old French histories, however, have been shown to manifest the anxieties of an aristocracy in decline. The majority of illuminated Weltchroniken, in contrast, offer a more confident view, with anecdotes and images celebrating the structures and technologies of expanding urban environments, and those that do include tales of kings tend to cast the rulers as legendary adventurers, more engaged with the magical than the administrative realm. Finally, readers familiar with the landmark early printed Nuremberg Chronicle (1493), compiled by Hartmann Schedel, might ask if manuscript Weltchroniken were simply less developed versions of that celebrated strain of incunable. But the manuscript World Chronicles and Schedel’s printed productions are quite different in approach. The Nuremberg Chronicle rushes through historical accounts from Creation to the Incarnation of Christ and grants the most space to often dry prose tellings of more recent events, with a focus on royal and papal regimes and urban history.

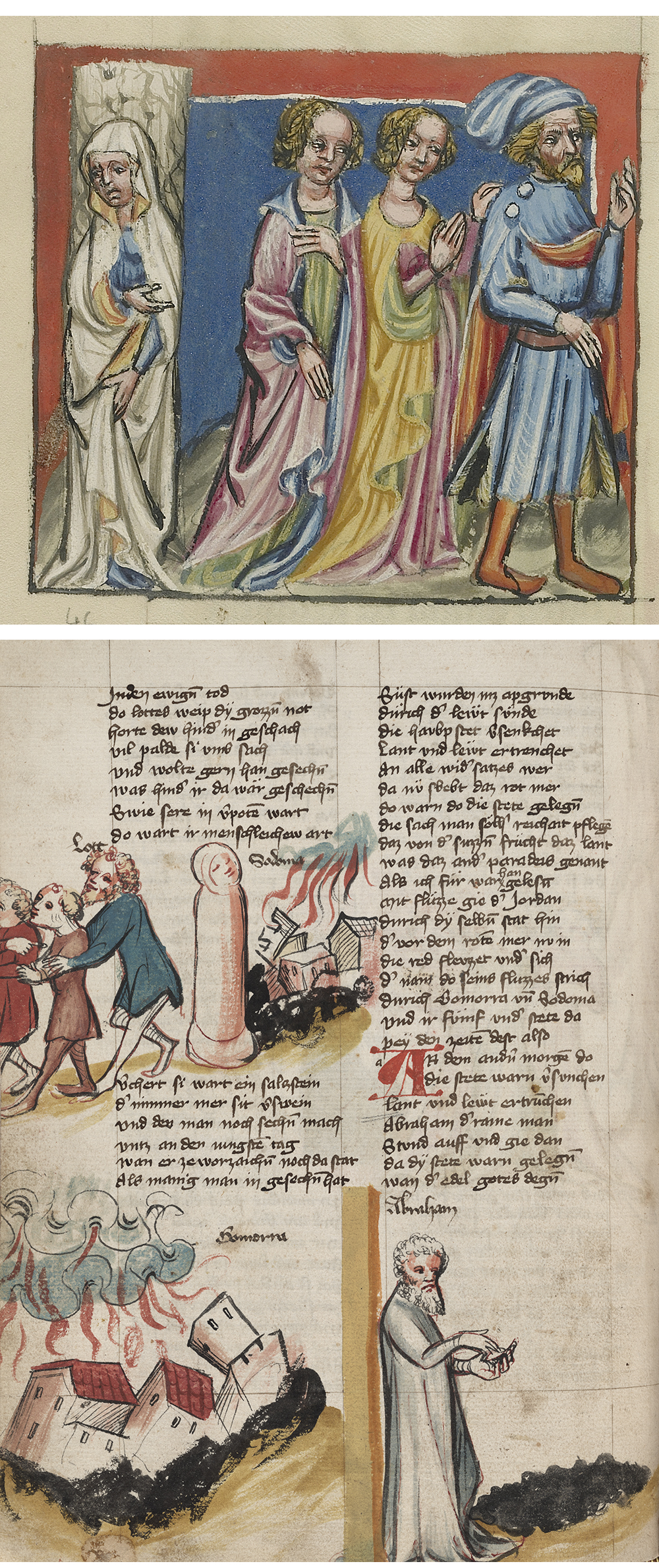

The vernacular, versified, hand-copied, and illuminated Weltchroniken, in distinction, offer expansive yarns concerning Old Testament patriarchs and stories connected to the Trojan War, stretching and swelling these, along with legends related to more recent history, and inserting profuse, lively, and often comical anecdotes. These transformed and repackaged tales ultimately seem to be geared toward edification and entertainment, in a manner parallel to today’s televised historical dramas.

Rudolf von Ems (active 1230–50) is the poet most frequently linked today with the vernacular Weltchronik genre. Rudolf was a member of the ministerial estate of the Vorarlberg region in Austria, and he penned his chronicle for King Conrad IV, son of Emperor Frederick II. A second author whose verses are found in illuminated Weltchroniken has come to be known as the Christherre-Poet because of his text’s opening invocation of Christ, and scholars call his composition the Christherre-Chronik. This author appears to have been a clergyman, writing between about 1254 and 1263. The final key author in the Weltchronik genus is Jans der Enikel (“Jans the Grandson”), also known as Jans Enikel or Jans von Wien (active 1271–1302). Jans was a member of a high-ranking patrician family in Vienna, and his chronicle likely was created between 1272 and 1280. All three authors announce the intention to recount world history from Creation to the present moment, but only Jans der Enikel makes it all the way to the era of the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick II, with a composition of 28,958 lines. Rudolf’s text, in contrast, breaks off at line 33,346 in the story of Solomon, and the Christherre-Poet gets only as far as the first book of Judges with the tale of Adoni-Bezek, at line 24,332. Unsurprisingly, given the distinctive milieus in which they emerged, the texts of these various Weltchronik authors range in tone. Rudolf often is characterized as being courtly or even imperial in style and encyclopedic in his approach. The Christherre-Poet is recognized to be a cleric, presenting his account of history in a theological framework. And Jans der Enikel exhibits an interest in secular daily experience, with verses that particularly celebrate urban life.

The transmission history of the Weltchroniken composed by Rudolf von Ems, the Christherre-Poet, and Jans der Enikel, however, demonstrates that by the mid-fourteenth century, audiences had little interest in the distinctive styles of these individual authors, favoring manuscripts that treated the foundational World Chronicles as raw material to be mined, excerpted, recombined, and spiffed up with illuminations.

The fashion for illuminated Weltchroniken did not arise spontaneously, but rather can be taken as a popularization of long-standing traditions. That is, the authors who composed Middle High German World Chronicles built upon trends in history writing that took shape in the twelfth century and that drew on earlier precedents. In Latin Christendom, the fundamental model and source for any consideration of the remote past was scripture, with an understanding that the biblical books from Genesis on offered real accounts of the adventures, triumphs, and defeats of the heroes of yesteryear. The organization of the Bible into narratives surrounding key figures such as Adam, Noah, Moses, the kings of Judea, Daniel, and Christ informed the development of a notion of history unfolding according to a divine scheme in a succession of six ages of humanity, as codified by Augustine. Beginning around the 1120s, theologians attached to the Abbey of Saint-Victor in Paris committed themselves to discerning this sacred plan for history, spearheading vigorous inquiries into the primary or literal (as opposed to the allegorical or tropological) sense of scripture. Such investigations seem to have motivated Peter Comestor to compose the Historia scholastica (c. 1150), an extended biblical paraphrase tracing the progress of humankind from Creation to Christ’s Resurrection.

Because it is plain that Peter Comestor inspired the Weltchronik authors, it is worthwhile to recognize this cleric’s innovations in his approach to telling the story of humanity. Comestor does not simply put the authoritative text of the Vulgate in his own words. Instead, he summarizes, expands, and freely reworks his core biblical texts, making his accounts historically and geographically specific by drawing details and larger passages from sources including contemporary exegesis, Josephus Flavius’ Antiquitates Judaicae (c. 94), and midrash (through the filter of Christian authorities). Comestor, moreover, fills in the picture of world history by periodically referencing events occurring outside the biblical narratives, what he calls incidentiae, an approach echoed and greatly amplified in many Weltchronik redactions. So, for example, inserted within the Historia scholastica’s discussion of Elon the Zebulonite (Judges 12:11) is the observation: “At that time Paris abducted Helen and the ten-year war [Trojan War] broke out. Memnon and the Amazons brought reinforcements to Priam.”

Rich in narrative appeal, the Historia scholastica gained an audience beyond the theological circles of its origins, circulating in Latin, but also vernaculars ranging from French and German to Castilian and Portuguese. The work survives in more than eight hundred manuscripts dating from the twelfth to the early sixteenth century and is credited with being a chief means through which the Bible gained popularity among the laity. Textual analysis reveals that Rudolf von Ems used the Historia scholastica as a chief source and inspiration, along with the Vulgate, Josephus, and other texts. And it is likely that the Christherre-Poet and Jans der Enikel similarly had a copy of Comestor’s history within reach, along with other historical compendia, such as Gottfried of Viterbo’s Pantheon, as they composed their chronicles.

An alternate textual tradition—that of the imperial chronicle—similarly inspired the Weltchronik poets. Otto of Freising and other twelfth-century monastic authors composed what are often termed “universal chronicles” in Latin prose. These typically begin with Creation, move through scriptural history, and then address ancient Greek and Roman leaders and the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire, presenting the post-biblical material as a series of biographies. A versified and vernacular imperial chronicle, an inflection on the established models, was composed in Regensburg sometime between about 1126 and 1150.

This Kaiserchronik begins with the era of Julius Caesar and continues to the mid-twelfth-century moment. In jaunty Middle High German couplets, the Kaiserchronik author insists on the truth of his tales—from an account of the Romans slaying Caesar and hoisting his remains on a column all the way past stories of Charlemagne. In between, the narrative relishes the exploits of dastardly rulers such as Nero or takes readers behind the scenes to intimate exchanges such as those between Justinian and his wife, all in all functioning as a founding work of popular history.

The Weltchronik presentation of the story of world history as a series of episodes associated with key characters from the scriptural patriarchs through the heroes of the Trojan War to rulers of the medieval era is analogous in structure to the Kaiserchronik. More directly, Jans der Enikel, the only one of the original World Chronicle poets to carry his narrative all the way to the post-biblical age and beyond, directly lifted and reworked passages from the Kaiserchronik. That said, the tone of Jans’ text is less reverent than this source, with Jans augmenting his work with generous doses of humor and dialogue, as well as legendary vignettes apparently drawn from folk tales.

These illuminated World Chronicles draw on theological and historiographical textual developments of the high Middle Ages. But they constitute a distinctive genre owing to their status as illustrated books whose appeal likely lay in their lush and dynamic imagery. It is particularly noteworthy that, while some Weltchroniken feature traditional illuminations, painted in tempera and enclosed in frames inserted into breaks in text columns, many of the manuscripts are adorned with pictures that hover in the margins, the figures appearing to have the potential to bound off the page and fall into the lap of the reader-viewer. Moreover, once paper manufacture began to flourish in the southern part of the Holy Roman Empire around 1390, the majority of illuminated Weltchroniken from the region were made in this new medium, inviting artists to experiment with the dynamic pictorial effects of washes.

Internal evidence in illuminated Weltchroniken allows for speculation about the original audiences and conditions of reception for the works. Colophons, dedication images, and heraldry found in ten witnesses lead to the conclusion that the manuscripts were prized by members of the lower nobility, patricians, and high-ranking burghers. More specific to the manuscripts at the heart of the current investigation, a preponderance of iconographic themes pertinent to and celebrating urban life suggests that World Chronicles held particular appeal for those who dominated city industry, commerce, and governance in Bavaria and Austria in the late Middle Ages. Moreover, the versified form of the chronicles and internal references in the texts indicate that Weltchronik manuscripts often were read aloud, likely as evening entertainment for the well-to-do. The sphere of the illuminated World Chronicle is one where the urban laity claim center stage and aim high, telling the legends of the past in their own words and, in the process, uttering full-throated celebrations of the progress of the human story.

Reprinted with permission from The Illuminated World Chronicle: Tales from the Late Medieval City by Nina Rowe, published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2020 by Nina Rowe. All rights reserved.