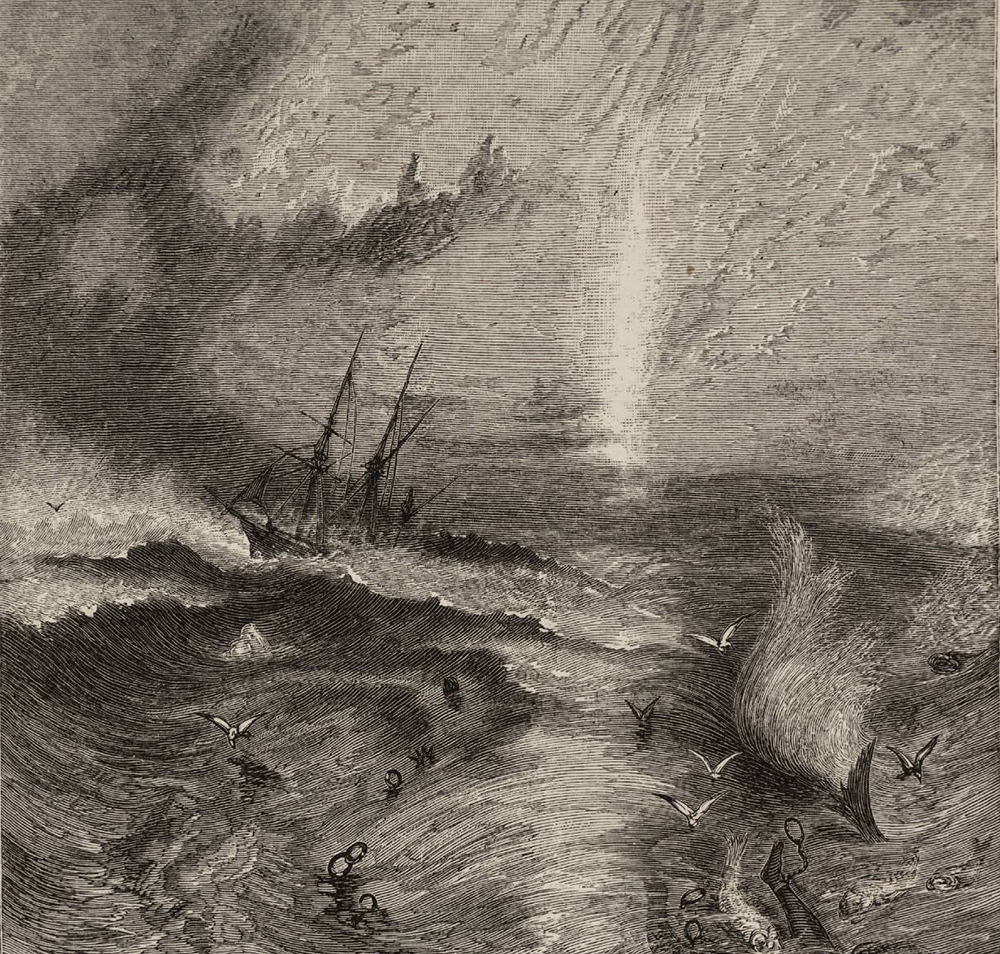

The Portuguese Slaver Diligenté captured by H.M. Sloop Pearl with 600 Slaves on Board, Taken in Charge to Nassau, by Lieutenant Henry Samuel Hawker, 1838. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

On May 5, 1825, the crew of the French brig Le Jeune Louis gathered together shortly after their surgeon, Denis Béjaud, died of dysentery, the same disease that had killed the ship owners’ representative on board, Jean-Baptiste Ménard, less than two weeks before. Probably sitting around a table in the captain’s cabin, they set out to write and sign a short declaration in which they explained the despairing situation they found themselves in. As they sailed in the vicinity of Ascension Island heading for Cuba with a human cargo in their hold, they lamented the ravages that dysentery and ophthalmia had caused both to themselves and to the slaves. Affected by these two diseases—and probably also by others they did not mention—they attempted a head count of the remaining Africans, noting that out of the 344 they had embarked near Cape Formosa in the Bight of Biafra, 304 remained alive, but were all suffering from one or more diseases. At sea, far from their desired destination, and being “unable of caring for the cargo, and hardly able to maneuver the vessel” due to the blindness caused by the ophthalmia, they probably thought that all was lost, as each of them signed his name on the small sheet of paper.

By mid-June, however, 229 Africans and a handful of sailors, including the captain François Demouy, had made it alive to Havana, where the French consul, Jacques Marie Angelucci, and the cosignatories of the vessel took care of restoring their health and of justifying the voyage before the Spanish and French authorities, after producing many documents, which included the death certificates of a number of Africans. Before too long they also expedited the loading of the vessel, sending it back to Europe less than two months later with a cargo of sugar boxes belonging to Cuban planter and prominent slave trader Gabriel Lombillo.

Perhaps better than any other, the case of Le Jeune Louis encapsulates the dangers associated with slave-trading expeditions to the coast of Africa during the illegal period that followed the signing of bilateral treaties between Britain and a number of slave-trading nations and states. Not only were the crew and the slaves exposed to fatal, debilitating, and incapacitating diseases, but within days of departing from the African coast they were left without the man responsible for the hundreds of slaves they had on board and, more significant, without their only health practitioner. In addition to all these tribulations, Le Jeune Louis had been previously stopped and searched at least twice by anti-slave-trade patrols since departing from Bordeaux, and had been forced to remain in the Bight of Biafra for approximately four months, sailing back and forth to the island of Principe, until a full human cargo was finally procured.

Slave ships like Le Jeune Louis turned into shared spaces where disease struck the overwhelming majority of those who were on board during the Middle Passage. That dysentery, ophthalmia, and fever attacked and claimed the lives of French slavers and enslaved African alike reveals the precariousness of human life and the limitations of medical treatment to combat these diseases.

In particular, for the crew of Le Jeune Louis, spending four months in the Bight of Biafra seems to have become a death sentence for many: a long exposure to slave-trading contact zones, where diseases—tropical and otherwise—were exchanged on a regular basis took a large human toll, both among them and among the Africans they crammed in the bowels of the vessel.

Slave ships were archetypical contact zones. On them, African slaves and their captors lived in a common, reduced space for weeks or months at a time, sharing air and fluids. As a result, a diverse variety of viruses and bacteria were also exchanged. By the time the slave trade was declared illegal in the early nineteenth century, health practitioners throughout the Atlantic knew this all too well. They were aware of the dangers associated with sharing such spaces at sea, far from any other medical facilities, and they often discussed them in their work.

The reality was that the slave ship’s environment was just as lethal as the geographical ecosystems where the diseases carried on board had originated. This was especially the case after the slave trade was banned by most of the Atlantic states from the mid-1810s onward. The resulting modifications in the shipping and accommodation of Africans on slave vessels as a result of the work of anti-slave-trade patrols led to hurried processes of loading the ships, often overlooking such thorough health inspections of enslaved men, women, and children as had taken place in the previous decades.

These changes were widely discussed at the time by anti-slave-trade cruisers, by diplomatic officers, and even by slave dealers across the Atlantic. Although slave vessels’ sizes, speed, and conditions on board changed at times dramatically over the years, the existing historical evidence points to an overall worsening of the conditions during the Middle Passage after the slave trade became illegal. Regardless of their respective sizes, overcrowding became a main feature of the slave trade during this period. Practically every one of the documented voyages for these years reveals ghastly conditions on board. Reduced and dirty spaces for human habitation, lacking clean air; spoiled water and food; punishment, tortures, and rapes; ever longer journeys; slave revolts; encounters with privateers, pirates, and anti–slave-trade patrols; and particularly the ravages of disease—all combined to create some of the most desperate conditions ever experienced by human beings in the modern world.

Slave dealers were not impervious to some of these episodes and maladies, either. The instructions they were almost always given at the start of their transatlantic voyages suggest that investors and owners of slave-trading expeditions were keen to avoid risks, particularly those concerning the possible spread of harmful diseases among their human cargo.

In 1839 the captain of the Brazilian vessel Especulador, Francisco Jozé de Abranxes, was prompted to carry out a slave-trading voyage to Anha, in Mozambique, making sure that the slaves he transported would arrive in the best possible conditions, as the ship owner, Jozé Joaquim Teixeira, confessed to be tired of suffering setbacks in his slave-trading expeditions. Almost at the same time, in Havana, Pedro Martínez recommended slave-ship captain Andrés Jiménez—later on the main slave dealer at the Gallinas River—“to treat the bultos [slaves] as well as he could,” since his job would be judged according to the conditions in which they would arrive. Jiménez was also strongly encouraged to use his experience in order to avoid any possible slave revolts during the Middle Passage.

In spite of the occasional efforts to take care of human beings who were unavoidably crammed within small, filthy, hot spaces, diseases were a main feature of the Middle Passage. Health practitioners often shipped on slave vessels to look after both the human cargo and the crew. In some cases, these practitioners were Westerners who had received medical education in Europe or the Americas. On the Voladora, in 1829, the surgeon was one “Doctor Juan Hidalgo,” a native of Rota, near Cádiz, who was said to be “unmarried and a professor of medicine and surgery.” Likewise, when in 1854 the ship La Luisa was captured off the mouth of the Manatí River near Trinidad in southern Cuba, the vessel’s surgeon, Joaquim Cordeiro Feijóo, was said to be a member of the Society of Medical Sciences in Lisbon and an experienced surgeon who had been attached to the Portuguese troops in Luanda in previous years.

In most cases, however, health practitioners seemed to have come from more humble backgrounds, and some ship officers, boatswains, or cooks doubled as surgeons on board of slave vessels. African-born and Creole practitioners, called sangradores, were the norm for many expeditions during the period. For example, in 1821 Alexander Cunningham and Henry Hayne, British Mixed Commission court judges in Rio de Janeiro, had the opportunity to interrogate a man named José Joaquim de Moraes, who was described as a free black or preto forro “of Gêge nation,” who confessed to be a “schooner’s sangrador,” a profession for which he was officially registered at Rio de Janeiro. Manoel Francisco Silva, also an African-born free man of Gêge nation, worked as a sangrador on board the brig Bom Caminho two years later, while Estanislao Ysidro, a Creole born in Brazil, was recorded as the sangrador of the schooner Bela Eliza in 1824. Sangradores were usually African-born or African-descended health practitioners who had applied and attained official licenses from the Brazilian authorities to exercise their bloodletting knowledge on land and at sea. According to historian Tânia Salgado Pimenta, sangradores were at times “the only therapeutic recourse for those who were sick” on board ships, thus becoming essential for the success of Portuguese and Brazilian slave-trade expeditions to Africa after 1820.

The daily work of sangradores, surgeons, and other health practitioners was a harrowing one, fraught with deadly hazards and meager rewards. Slave-trading crews and the slaves they embarked were often the victims of endemic and epidemic diseases difficult to diagnose and treat, even when medical supplies were available. A number of narratives and documents, including correspondence, left by slave traders illustrate the environment to which health practitioners and their patients were exposed. References were common to sick and dead captains and crew members—including health practitioners.

African slaves fared much worse. The private letters written by some of the slave-ship captains of the period to their employers and partners shed light on the morbidity and mortality that often affected those men, women, and children they carried against their will across the ocean. The captain of the Brazilian schoonerbrig Aracaty, Joaquim Antônio Lima, in a letter sent to his partner Joaquim Pereira de Mendonça in early 1842, described in detail the loss of several hundred slaves on his previous slaving expedition to Africa, and reported losing a number of slaves on his present voyage before being detained by a British man-of-war after departing for Rio de Janeiro. In a similar incident, the crew of the Vigilante, a Spanish slave vessel that had been attempting to get a human cargo near Cape Lopez in 1838, sailed at once for Santiago de Cuba after the captain concluded that there was no point in remaining any longer off the coast of Africa, as the slaves they had bought were dying faster than they were able to replace them.

The cases of other equally full and lethal slave ships filled the reports of Mixed Commission and Vice-Admiralty courts, often leading to renewed calls for the abolition of the slave trade. Rarely, however, did the Africans have the opportunity to describe their own traumatic experiences in the Middle Passage. One of the few exceptions was the case of Antonio and Dominga, two young Africans—about eleven or twelve years old—who had been sold and embarked at the port of Boma on the Congo River sometime in late 1857 or early 1858. Antonio and Dominga, whose real names were Bata and Manyeré Curo, recounted their difficult time before Spanish colonial officers in Havana weeks after their arrival. They testified that during the Middle Passage they were given only one cracker per day, and “that they were all very hungry, that they would ask for something to eat, and they would get nothing.” They also recounted that as many as fifty of their companions had died of disease and hunger, and that their bodies had all been invariably “thrown to the sea.”

The testimonies taken from Africans aboard the schooner Arrogante in 1838 were even more striking, as some of them accused the ship’s sailors of murdering one of the Africans, and of subsequently cooking his flesh and serving it with rice to the rest of the slaves.

Excerpted from The Yellow Demon of Fever: Fighting Disease in the Nineteenth-Century Transatlantic Slave Trade by Manuel Barcia, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2020 by Manuel Barcia. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.