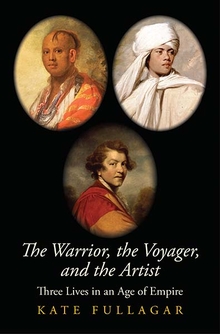

Self-Portrait as a Deaf Man, by Joshua Reynolds, c. 1775. Wikimedia Commons.

The evening of December 10, 1776, was exceptionally cold. It had been a trying winter for Londoners in more ways than one. News from across the Atlantic was getting worse every day, and no one seemed to agree on the best path forward. Some thought the American colonists were justified in their break for independence. Others believed that hanging was now not punishment enough. The weather didn’t help. Yet, undeterred by it all, that night the members and students of the Royal Academy of the Arts scurried up the steps into Somerset House on the Strand for their annual prize-giving ceremony. Perhaps they were eager for some distraction from the splintering of their empire. Perhaps they wanted simply to find out who were the medal winners for that year and to listen to their president’s seventh formal address. The president, Sir Joshua Reynolds, was fifty-three years old in 1776. He had held his position as inaugural head of the Royal Academy for seven years. The audience was by now used to his low-toned Devonshire accent and his ruddy if commanding appearance. They were also used to the message with which he opened his address. “The first idea of art,” he declaimed, is to show the “general truths” of humanity, which are all indisputably “universal.” The artist should never privilege those quirks that make a sitter distinct from everyone else because that would draw attention to what makes humans disagree with one another instead of to what unites them.

About halfway into his speech, the president, unusually, changed tack. He brought up the tricky issue of what artists should do when faced, nonetheless, with sitters who bore such pronounced quirks that they challenged his core idea of human universality. To illustrate the problem, Reynolds offered the examples of an ocher-daubed Cherokee and a tattooed Tahitian. Most listeners in the room that night knew that Reynolds spoke from experience in invoking such examples. Just a few months earlier Reynolds had exhibited his portrait of Mai, the first Pacific Islander to visit British shores (who was really from the island of Ra‘iatea but was thought by most Londoners to be from nearby Tahiti). A dozen years before, Reynolds had painted the portrait of a Cherokee visitor, equally celebrated, called Ostenaco.

Today, these two Reynolds paintings are rarely connected. They have met with starkly opposing fates. At the start of the twenty-first century the portrait of Mai—grand, beautiful, idealized—caused a controversy when it sold to a foreign buyer for a record £10.3 million. At the time, this was the second-highest price ever paid for a British work of art. The controversy continued when the British government placed an export bar on the piece to prevent it from leaving the country, citing the portrait as a “national treasure,” an “icon of the eighteenth century,” and a “vivid testament” to enlightened multiculturalism. The export bar still applies, making Reynolds’ Mai the longest-detained work of art in British legislative history. The portrait of Ostenaco, by contrast, is seldom discussed. Smaller, quieter, more subdued, it has long been housed in an American museum as an ethnographic artifact.

Back in Somerset House, though, during the dying days of Britain’s Atlantic-based empire, few would have questioned the connections between either the paintings or the sitters. Everyone remembered the visits by Ostenaco and Mai. Both had been popular arrivals, tracked by a burgeoning press and by substantial crowds who were just then learning the ropes of celebrity culture. Ostenaco had arrived in London in the summer of 1762. He was in his late forties by then, a seasoned diplomat for the Cherokees with an even longer record as a distinguished warrior. He had been a chief prosecutor of the deadly Anglo-Cherokee War of 1760–61 but came now to secure the war’s termination with King George III of Britain. During his ten-week stay Ostenaco took in tours of London’s docks, cathedrals, jails, parklands, and tavern scene. He returned home more confident of the Cherokees’ relationship with the British, but he was not to know that the British were soon to find their status in America ripped to shreds from within. Ostenaco would become caught up in the subsequent settler revolution in complicated ways.

The Ra‘iatean man, Mai, had come to Britain under less official auspices. He had made his way in 1774 by jumping on board the returning leg of James Cook’s second voyage to the Pacific. Cook, although reluctant, had conceded to his joining because he assumed that Mai (incorrectly called Omai in England) might serve one day, like Ostenaco before him, as a kind of broker between Britain and a “New World” indigenous society. For his part, Mai had no interest in diplomacy. He wanted simply to acquire the special firepower he had seen Europeans deploy sporadically in his home islands over the last six years. Mai was still a young man when he arrived in Britain—around twenty-one or so—and he enjoyed a longer stay than Ostenaco, returning after two years. He took in even more sights than his Cherokee predecessor had, attending theaters and museums in addition to the palaces and pubs. Mai too became embroiled in conflict upon his return home, though in his case it was mostly internal to the various indigenous peoples surrounding Ra‘iatea.

Reynolds was younger than Ostenaco but older than Mai, middle-aged when he encountered the two men. He was already a famous painter in 1762. By the time he met Mai in 1774 he was the undisputed leader of Britain’s art world. Reynolds’ interest in representing people from other cultures was a constant, if unrecognized, undercurrent in his life. Though he was never wildly successful at its portrayal, the exotic attracted Reynolds as a testing ground for his beloved theories about human sameness. He was better known for representing the leading men and women of Britain’s unfolding empire. He died in the 1790s amid British fears of a wholly new political order emerging just one narrow channel away.

Did either Ostenaco or Mai think back on the calm, pinkish, and, to them, rather short man who worked to reproduce an image of his face? The answer is almost certainly no. Upon returning to their respective homelands, both immediately became involved in local dramas that had always claimed more of their attention than anything the British had ever done. As this lack of attention makes clear, indigenous people were often less impressed with Europeans than Europeans were with them—or at least less impressed than Europeans have ever since liked to believe.

The lives of Ostenaco and Mai reveal how the intrusion of empire into indigenous societies was momentous but never total. It was important but not overdetermining. Ostenaco’s Cherokee society was affected by the advancing influence of colonists from Charleston, Williamsburg, and other places. But it similarly affected those settlements in turn: Cherokee existence and actions influenced colonial strategies, capacities, ideals, and projections. Mai, for his part, witnessed firsthand the violence and disease that imperialists brought to his society, but he managed to use empire for his own ends more pointedly than empire ever managed to use him. Both Ostenaco and Mai took the even more notable liberty, on occasion, of ignoring empire altogether—to the great frustration if not complete disbelief of observing Britons. Though the immense scale of indigenous dispossession through the modern era suggests an all-consuming history of degradation and control, individual stories insist on a bumpier and more negotiated process on the ground. These stories are harder to find than those of defeat, but they are crucial to any serious attempt to include more of the voices actually involved in the making of the contemporary world.

Did Reynolds think of his sitters more than they thought of him? Apparently, since he remembered them in his annual speech of 1776. But his memory was sporadic and unpredictable. He did not mention Ostenaco or Mai again in any written source. He did keep both portraits of them in his studio all his life but displayed one as an example of painterly prowess rather than imperial commentary and hid the other away from public view altogether. Reynolds’ patchy and curious remembrance of Ostenaco and Mai shows that Britons had more conflicted attitudes toward empire in the eighteenth century than the record of later imperialism indicates.

Joshua Reynolds was not a radical in any sphere of life. He consorted with, painted portraits of, and benefited enormously from the leading imperialists of the age. At the same time, though, he showed signs of hesitation and worry about his nation’s expansionist activities. Several of his key paintings include elements of doubt about imperial endeavor. Sometimes he revealed doubt by refraining from imperial representation altogether when the reverse was most expected.

To simply see empire’s destruction is to miss seeing also how individual indigenous people absorbed, manipulated, adjusted, snubbed, or otherwise survived empire’s force. Only the recognition of such survival can explain indigenous lives in the present and, more important, offer usable histories for indigenous futures. Likewise, to identify jingoism as the sole possible domestic attitude to empire is to overlook how empire permeated British life for some as a controversy. To see both pro- and anti-imperial views provides a powerful guide to the fault lines along which the British empire stumbled and floundered even while it continued to grow. It emphasizes the contingency, the potential fallibility, and, in the end—most important—the breakability of enterprises that appear in all other senses intractable.

The British empire did not rise like the sun, uncontested by either its perpetrators or victims. It was, and is, resistible. British imperialism deserves no nostalgia today. On the contrary, it requires histories that reveal the detail of some of the actual lives involved, in order to absorb the problems inherent in its formation as well as the achievement of those who endured it. There is precious little earlier literature on either Ostenaco or Mai, through any lens. But published work that does exist always situates these figures as examples of cross-cultural encounter. This means it focuses on the moments when they met or fought or befriended imperialists. “Encounter histories” have been vital in recovering the nuances of imperial-indigenous contact, but they inevitably raise the role of imperialists to at least costar status. Discovering the whole life of an eighteenth-century indigenous person—upon which imperialists impinged as just one of many actors or for just a finite period—puts empire into a more modest place. It also helps keep indigenous people the main characters in their history.

Unlike Ostenaco or Mai, Reynolds is a canonical figure—one of the Great Dead White Males who has, since death, thrived on the historian’s addiction to those who made a big impact on impactful societies and who left plenty of written sources for writing-obsessed posterity. Reynolds has prompted numerous studies, some of which are full-life biographies.

Barely any, though, see Reynolds as an imperial subject. This is strange enough given the huge proportion of his paintings devoted to the generals, merchants, princes, memsahibs, and scions of Britain’s expansionist experiment. It is even more strange given how much empire was transforming, during Reynolds’ adulthood, everything about his society, from its armed forces to its commercial outlook to its favorite breakfast beverage. The reluctance derives in part from Reynolds himself, a man who worked assiduously while alive to mold an apolitical reputation.

If seen as an imperial subject, however, this sense of Reynolds as apolitical starts to look less about being disengaged than about being conflicted when it came to Britain’s empire. Caught between an aesthetics that understood humanity as universal and a society that needed increasingly to justify exclusionary colonization, Reynolds often bounced between both positions. Sometimes he even combined them in one work. To uncover this specific ambivalence in one British life is to grasp the divisions at home regarding imperialism through empire’s burgeoning years.

Reprinted with permission from The Warrior, the Voyager, and the Artist: Three Lives in an Age of Empire by Kate Fullagar, published by the University of Yale Press. © 2020 by Kate Fullagar. All rights reserved.