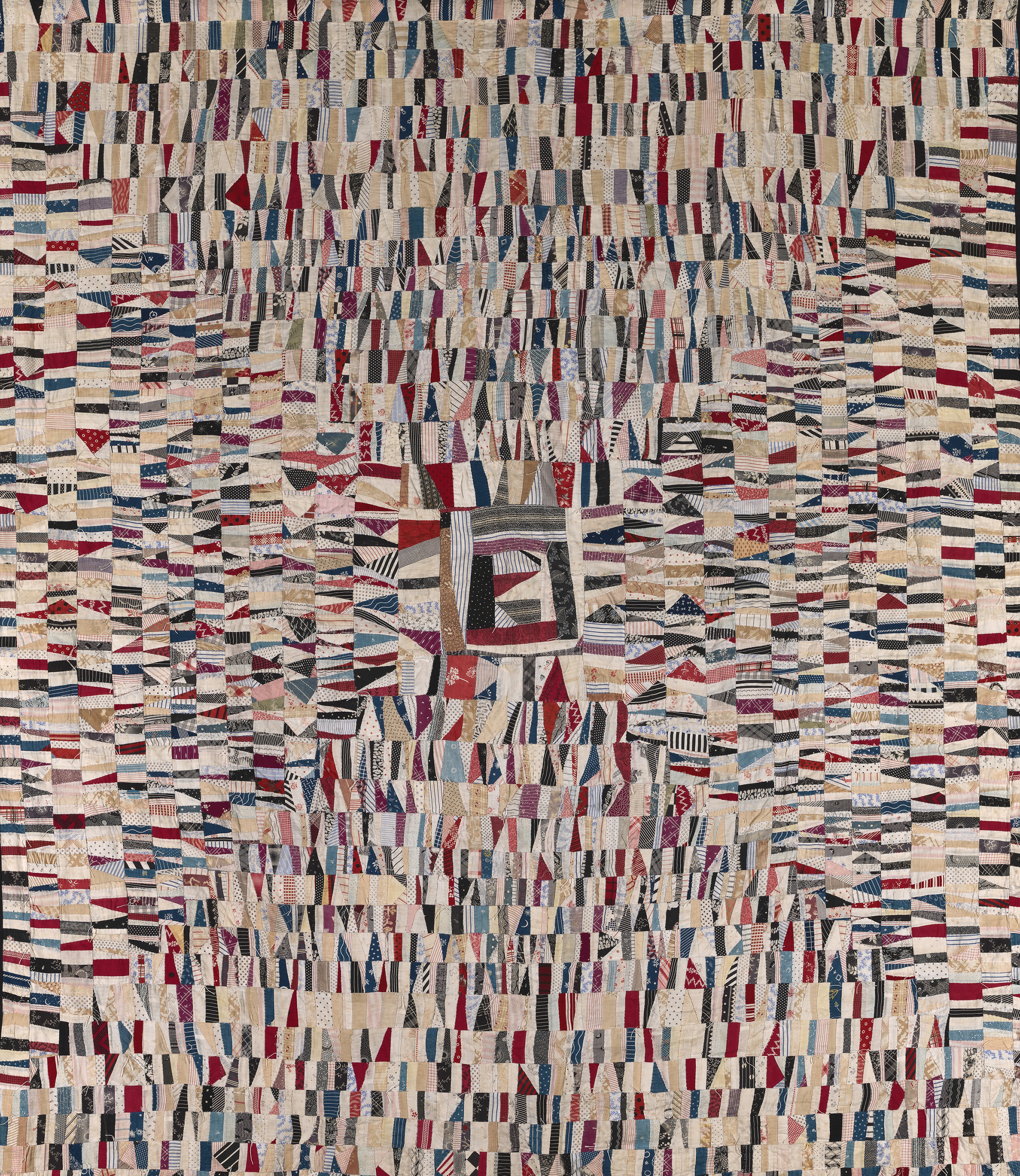

String quilt, Housetop pattern, c. 1930. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Corrine Riley and museum purchase through the Barbara Coffey Quilt Endowment and the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.

In 1979 the famed African American writer and artist Ralph Ellison wrote of African Americans in the southern United States: “As slaves…they knew that to escape across the Mason-Dixon Line northward was to move in the direction of a greater freedom. But freedom was also to be found in the West of the Old Indian Territory.” This poetic statement by a son of Oklahoma is representative of the cultural cachet Indian Territory held for people of African descent throughout North America. During and after enslavement in the United States, the West, and especially Indian Territory, represented freedom, possibility, and amelioration. Rumors that Indian nations would take in runaway slaves or that enslaved people in the Five Tribes—the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole Nations—were treated better than enslaved people owned by whites bred this mythology. While the truth behind these beliefs was far more complex, the West proved to be an attractive destination for an increasing number of Southern African Americans after emancipation.

This postwar exodus was largely the result of congressional Republicans’ failure to successfully legislate the receipt of free land within the United States for African Americans. The bill that created the U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau, an organization that would later provide freed African Americans help with finding employment, locating lost loved ones, and general acclimation to freedom, was originally designed to include a provision for land that built on an idea of Gullah Geechee women and men from the South Carolina islands, relayed to General William Tecumseh Sherman. In the final months of the Civil War, as he prepared for his last invasion of South Carolina, General Sherman noted the sentiments of African Americans in the region, who asked for nothing more than to be able to claim ownership of the land they had worked for generations and which their owners had deserted. In a wartime measure designed to respond to this desire, but more so to provide resources for the many African Americans who had long followed and assisted his army, Sherman wrote his Special Field Orders No. 15, which provided for forty acres of land for each Black family in “the islands from Charleston south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the Saint John’s River [Florida].”

Congress’ attempts to codify the accommodations within Sherman’s order were unsuccessful. Various versions of the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill included a nod to the issue of Black landownership, from the first version that permitted African Americans “to occupy, cultivate, and improve all land which had been abandoned and all real estate to which the United States might acquire title within the rebel states” to the second, more radical iteration of the bill, which stated that “from the confiscated and abandoned Southern lands forty acres should be given to every male refugee or freedman as a rental for three years, thereafter eligible for purchase from the U.S. government.” It became clear that in order for the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill to be passed, the land section of the act would have to be discarded. The issue was made moot when President Andrew Johnson decided that one of his first acts as president would be to return confiscated land to those slaveholders who sought pardons.

Although whites and African Americans had emigrated from the United States to Indian Territory since the creation of the region as a Native outpost, their population numbers were largely insignificant until the late nineteenth century. Between 1890 and 1907, the Black population of Indian Territory (including both Indian freedpeople—Black people once owned by members of the Five Tribes—and African Americans) increased from 19,000 to over 80,000. The white population increased from 109,400 to 538,500 as a result of the Homestead Act and the opening of the Unassigned Lands. Throughout these other demographic changes, the Indian population remained stable at roughly 61,000.

The Homestead Act rule requiring citizenship (or naturalization) would seem to purposely limit African Americans’ access, as they were not yet considered U.S. citizens. In addition, though January 1, 1863, the date of effect for the Homestead Act, also marked the enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation, most African Americans were still enslaved at this time and did not have the ability to freely make their way to the West. The Homestead Act was also cost prohibitive in a number of ways. Most people of African descent could not afford to fulfill all of the terms: to pay to file an initial land claim (termed a “preemption” claim), to live upon and “improve the land” (which required building a home), to plow the land and tend it for five consecutive years, and, finally, to pay to apply for a land patent. Even if an African American woman or man could pull together the funds and resources required for these stipulations, they were still at a disadvantage. As petitioners were required to pay per acre for their preemption claim, monied whites had the ability to amass large tracts of land, privileging them even in this supposed bid for equality in western land access. These requirements also negatively affected poor whites. A number of white and Black Americans illegally squatted on lands, earning themselves the enmity of both Indians and Indian freedpeople.

As the twentieth century dawned, some Black editorial writers made plain their opinion that African Americans had a right to claim these gains for themselves. These writers and the Black settlers who heeded their call were actively willing to engage in settlement on lands they knew were set aside for Indians and Indian freedpeople. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, African American leaders supplemented their rhetorical overtures for increased migration, aimed at Black Southerners, with political and social arguments regarding their qualifications for landownership, aimed at whites.

In 1880 J.H. Williamson, a former slave, the longest-serving Black nineteenth-century state congressman (of North Carolina), and the founder of the Banner, a paper advocating for Black industrial education, testified in front of the Senate. As African Americans were leaving the South in droves because “in many of the Southern states the colored people are denied rights,” Williamson made a case for Black Americans’ ability to civilize the West, arguing that whites should support the creation of an all-Black state. Williamson juxtaposed the “civilized” United States where Blacks were murdered “because of their political opinions,” and “where the cry of relief from ‘negro rule’ ” echoed, with the untamed West, where one might be “scalped by the wild Indian,” maintaining that even life there would be preferable to the indignities African Americans suffered in the South with no recourse. Despite the presence of “wild Indians,” Williamson felt that the West offered African Americans the opportunity to “carve out [their] future destiny under the shining sun of heaven.” Williamson felt African Americans would quickly show they were preferable to Indians as neighbors to the United States. He asserted, “The Indians are savage and will not work…[in contrast], we, the negro race, are a working people. Should we emigrate we would endeavor to clear the forests and drain the lowlands, build houses, churches, schoolhouses, and advance in all other industries and work out our own destinies.” Williamson’s argument was couched in the approval of settler colonialism—a process that allowed for hardworking Black women and men to “clear” the lands of Native peoples and then prosper on them.

Williamson continued his argument by comparing the civilizing work African Americans could carry out in Indian Territory with that of “the first settlers at Jamestown and Plymouth Rock,” mentioning that they had encountered difficulties like “disease, starvation, and death” but overcame it all. So, too, Williamson suggested, would African Americans, if given the resources.

A statement made by Frederick Douglass highlights even progressive Black Americans’ willingness to engage in the settler colonial process in order to participate in western settlement. In a speech to the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1869, Douglass argued that “the negro is more like the white man than the Indian, in his tastes and tendencies, and disposition to accept civilization. The Indian…rejects our civilization…It is not so with the negro. He loves you and remains with you, under all circumstances, in slavery and in freedom.” Douglass used logic similar to that of white Republicans who advocated for Indian freedpeople’s land-development skills above those of Indians, positing that people of African descent were more closely aligned with white America’s march of progress than Native Americans. Douglass joined African Americans’ goals and behavior with whites’ by using the term our civilization.

In an earlier speech, “Land for the Landless: The Record of Parties on the Homestead Principle No. 20,” Douglass explained his belief in the value of settler colonial principles, specifically:

The proposed donation of the public lands to actual settlers—to the landless masses as free homesteads—the peopling of the national domain with an enterprising, intelligent, and hardy race of emigrants—transforming the savage wilderness into flourishing civilized communities, multiplying new states, and adding immensely to the wealth and productive industry of the nation [would] extend the area of freedom [and] would increase the political power of the North and West—the power of the people—would dangerously menace the perpetuity of the institution of slavery and the democratic slaveholding aristocracy built upon it.

Douglas knew that this land was not “free” and that it had not always been “the national domain,” that rather it had been taken from Indian hands. He also knew that American emigration into the region would change and worsen circumstances for Native peoples and impede tribal sovereignty. Yet he used the language of savagery and civilization to juxtapose what the region was allegedly like in Indian hands and what it might be like after the emigration of African Americans, who, in his imagining, were more similar to whites than were Indians in their ability to tame the land. While Douglass’ two speeches were given four years apart, they represented the sustained belief on the part of one of the most famous Black radicals of his time that African Americans deserved to share in the settler colonial spoils of the Native West.

The belief in the value of the settler colonial process extended to Black leaders in the West, such as Edwin P. McCabe, whose advocacy for Black resettlement culminated around the time of the creation of Oklahoma Territory. McCabe had been the first Black county clerk in Graham County, Kansas, in 1880—a place he had arrived in in 1878, seeking the promise of western paradise—and was elected as state auditor in November 1882. Four years later, after Kansas Republicans chose another nominee for auditor, McCabe left Kansas to realize his dream of a Black state in Oklahoma Territory, and in March 1890 he traveled to Washington, DC, to present to President Benjamin Harrison the idea of making the Unassigned Lands an all-Black state. While the president’s reaction is unknown, unsurprisingly many whites were not pleased.

Nonetheless, there were some whites who embraced the notion of an all-Black colony in the West, as it combined their ideas of segregation and colonization, allowing them to avoid the (imagined) difficulties of integrating former slaves into a post-emancipation society in the East. As early as the 1790s, white American thinkers—such as St. George Tucker, a lawyer and law professor; Anthony Benezet, the Huguenot abolitionist; and politicians including the Virginia magistrate William Craighead and future president James Madison—suggested the “northwest” as a site of a potential Black colony. In the nineteenth century, these ideas took on greater specificity as Native land opened up in Indian Territory and full African American emancipation was nigh. A few months after the Civil War ended, Senator J.R. Doolittle raised the issue anew. In September 1865 he wrote to President Johnson, “What lies west of the Indian Territory could be…given to the Indians. The remainder could be organized into a Freedman’s Territory for the colored soldiers [and] for all other colored men heads of families…there could be ample room in this territory to receive the full benefits of the Homestead Systems, of which you are the author.”

The majority of white Americans were no more willing to financially support this idea in the nineteenth century than they were in the eighteenth century. In both periods, white Americans presenting the idea of Black colonization within North America recognized that people of African descent had faced, or would face, discrimination in the confines of the United States; settlement elsewhere was preferable. But in shunting African Americans to another location, whites were simply declining to fix the problem in their own home, perpetuating the racism they claimed would not allow African Americans to live peacefully in the United States as free people.

For Black Americans, there were many reasons to want a separate territory: they desired freedom from harassment and racial violence and the ability to exercise the political, economic, and social rights they had finally won, while staying within the boundaries of North America and maintaining some sort of relationship with the nation that they had helped build.

Excerpted from I’ve Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land by Alaina E. Roberts. Copyright © 2021 University of Pennsylvania Press. Excerpted with permission of the University of Pennsylvania Press.