We all have many vivid memories of our founder and friend, Lewis H. Lapham, who died near Rome on the night of July 23-24 at eighty-nine.

He was of course celebrated for his elegant essays and incisive editing, most famously as the editor of Harper’s Magazine, followed by his work at the helm of Lapham’s Quarterly, which many have called a work of art. His ingenuity, skepticism, formidable work ethic, vast reading and often droll sense of fun, drew our admiration even in those cases when we might have disagreed with his contrarian and unpredictable opinions—political or otherwise.

Lewis was also one of the few major American literary and journalistic figures whose work spanned all the major media—print (newspapers and magazines), books, radio, TV, film (The American Ruling Class), and the internet; he was wisely wary about the last.

We laud his passion for showing readers the great value of historical knowledge, to individuals and the citizenry as a whole. He had come to see citizens’ knowledge of history as essential for a healthy democracy, and wide ignorance of it as ominous. That’s why he embarked on the arduous task of founding and preserving Lapham’s Quarterly—a publication like no other. And note that he was passionate not only about the selection of words but about the look of Harper’s and LQ. He had a strong eye for design, the apotheosis of which is the gorgeous Quarterly, to which he attracted a brilliant staff.

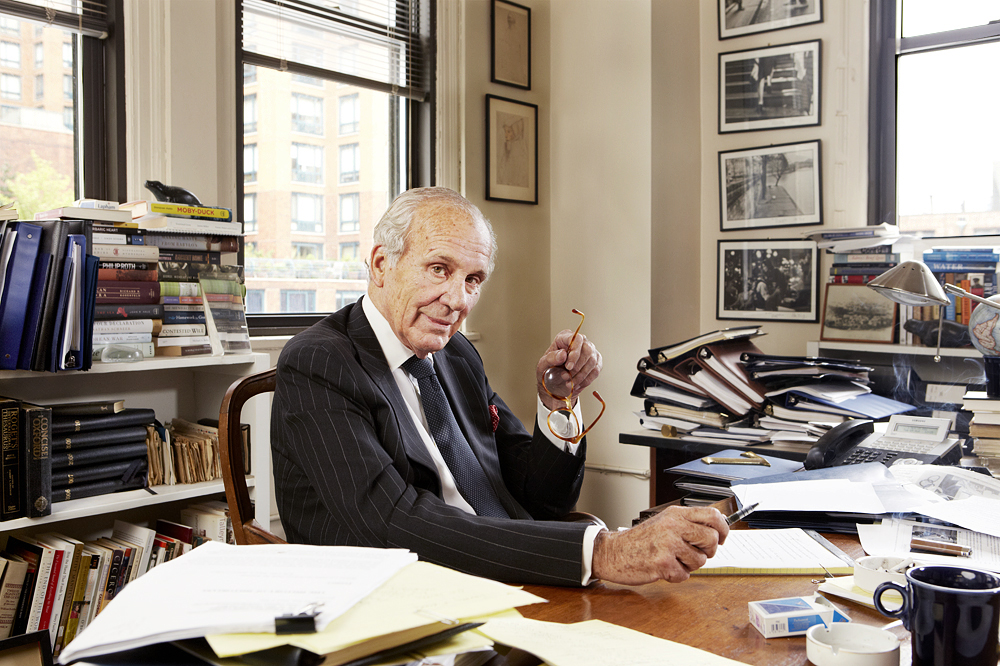

Others in the media in the past few days have published long and detailed descriptions of Lewis’ career and told of his memorable style, including the bespoke suits on his lean frame, his gold cufflinks, and his Parliament cigarettes. (His relentless smoking, however unhealthy, added a rather exotic and alluring layer to his patrician voice.)

Of course he had his quirks. We sometimes found his disinclination to ask for money for the Quarterly—was it a WASP thing?—frustrating. Was it tangled up with his desire not to be served but to serve? Or just shyness? And he could be briefly grumpy. But then, after all, he worked in a high-stress sector.

Lewis had a great gift for friendship, with the famous, the unknown, and those in-between. He was a man who showed enduring loyalty to friends, some of them of many decades, who treasured his company because of his charm, interest in the lives of others, his knowledge, and his anecdotes, many of them hilarious and more than a few self-deprecatory. A meal with Lewis, who had little interest in food but wasn't opposed to a convivial cocktail or two, was a treat. Some of us remember dinners with him that would end with us unsteadily but happily leaving a restaurant at midnight.

At the same time, he was a mentor to innumerable young and old writers. There are many who cite Lewis for their decision to enter, or stay in, the difficult worlds of journalism, literature, publishing and education. He was a devoted and patient teacher, as Lewis strove to, as he put it, to “turn C-plus articles into A articles.’’ He always seemed to be on the lookout for job opportunities for new and old friends. And he sought ways to help those down and out. He had (a sometimes idiosyncratic) emotional intelligence.

Up until a few days before his death, he was still reading and chatting with some of us on the phone about the news and books he was reading. And he was plotting out his memoirs. It’s sad that he wasn’t able to write them, though we can hope that a biographer will arrive to narrate one of the great American lives.

All of us in the Lapham’s Quarterly project will continue working to preserve and expand Lewis’ legacy of promoting the understanding of history. If you would like to contribute to our efforts, you can do so by clicking the donate button below.