Nearly every night at the Moulin Rouge bodies shook, eyes rolled, fingers trembled, faces grimaced, backs arched, and limbs bent at impossible angles. The bodies at the mercy of tics and spasms filling Paris’ asylums and Parisians’ imaginations were likely not far from the minds of those who watched the cabaret’s performers in the 1890s.

Singer Yvette Guilbert, thin and pale, stood stiff, “the absence of gesture [contrasting with] the almost diabolic rolling of her eyes and the grimaces and distortions of her bloodless face,” according to one observer. The clown Cha-u-kao bound her hair so that it stuck straight up, topped by a ridiculous yellow ribbon that matched her signature garish top. Cancan star La Goulue paused mid-dance to down patrons’ drinks, high kicking hats off heads, while the poet and novelist Jean Lorrain described Polaire miming “all forms of shocks and shaking” as she “twists, leans over backyard in the form of an arc, becomes upright...rolls her eyes into her head, meows, is in ecstasy.”

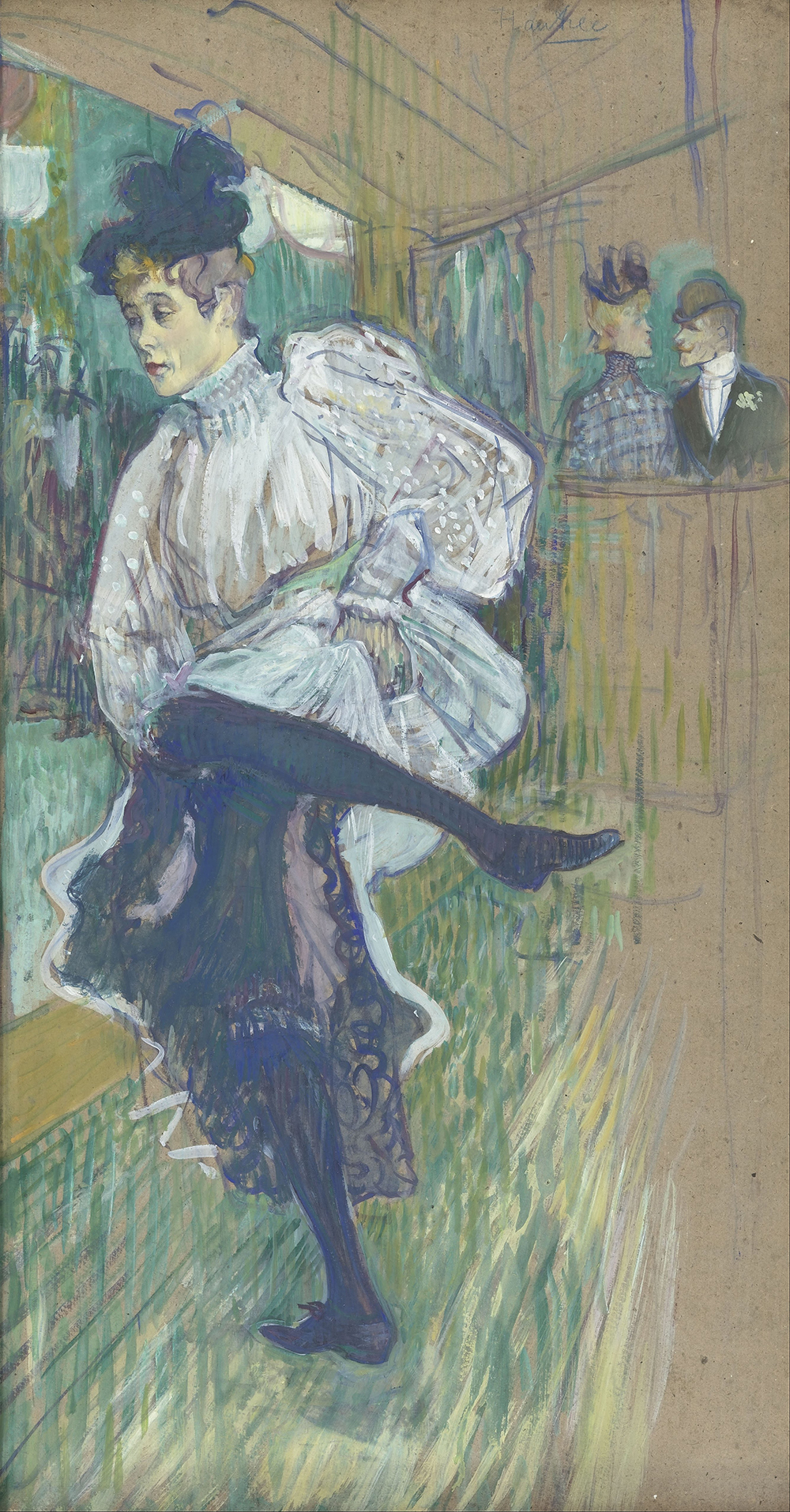

But even in the madhouse of the Moulin Rouge, one performer stood out: cancan dancer Jane Avril, known as Jane La Folle (“crazy Jane”) and La Mélinite (“dynamite”). “In the midst of the crowd, there was a stir, and a line of people started to form,” the writer Paul LeClercq wrote of one of her shows. “Jane Avril was dancing, twirling, gracefully, lightly, a little madly; pale, skinny, thoroughbred, she twirled and reversed, weightless, fed on flowers.” LeClercq remembered the painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec shouting his admiration.

By the time Avril had become one of the Moulin Rouge’s stars, she would have already known the frenetic steps intimately. She had been doing them for a decade, dancing, a little madly, both voluntarily and involuntarily.

In 1882 Jeanne-Louise Beaudon turned fourteen and could no longer control the twitching of her limbs nor the slow drooping of one side of her face. A doctor recommended that she check herself into Pitié-Salpêtrière, an imposing neoclassical hospital in Paris’ thirteenth arrondissement.

The Salpêtrière was, by the time Jeanne was admitted, an old and infamous institution. Its explosive name was derived from its original function as an arsenal for gunpowder (saltpeter is a common name for one of its key ingredients, potassium nitrate) in the sixteenth century. The building was retooled in the seventeenth century, transformed from an arsenal into an asylum for women. Later that century the Salpêtrière expanded to become a prison as well, housing criminals and eventually heretics. It was, in short, a convenient jail for any woman who was unwanted, from the insane to the sick, the prostitute to the penitent, the penurious to the incurable. When rumors spread that Paris’ inmates would be freed to take up arms with the royalists during the September Massacres of 1792, the Salpêtrière was targeted by the newly empowered revolutionaries, who called for the inmates’ execution. Convinced that an army was housed there, they dragged imprisoned women from the cells to be murdered in the courtyard. A contemporary print shows the carnage: bodies fill the foreground as the living are sentenced to death among a mob of men eager to shed blood for liberté, égalité, and fraternité.

After the September Massacres, Salpêtrière returned to being a hospital primarily dedicated to the treatment of women with a range of disorders, including choreas, palsies, neuropathies, and, most infamously, hysteria. When the physician Philippe Pinel—sometimes credited as the founder of modern psychiatry—was appointed chief physician three years after the massacre, he became famous for freeing seven thousand women from their shackles. (One of Pinel’s assistants more likely proposed the change, but history prefers a singular hero.) The act was restaged in paint a century later by Tony Robert-Fleury, who transformed the liberation into a melodramatic scene, replete with madwomen baring their breasts and writhing on the ground. The painting is overwrought (the women conveniently borrow poses from the Old Masters, and Pinel is too obviously cast as Christ-like), but the look of the madness is unmistakable: the women’s eyes are stereotypically blank, their bodies undisciplined and sexualized. It was a look that had been cultivated at the Salpêtrière for a century.

“History,” Michel Foucault wrote, “is the concrete body of becoming with its moments of intensity, its lapses, its extended periods of feverish agitation, its fainting spells.” History is a body, but the body is “inscribed on the surface of events.” In fin de siècle Paris, the body and becoming were both frenzied and uncontrollable, subject to seizures and spells. Illness spilled out of the confines of the Salpêtrière in photography and public demonstrations and thereby entered public consciousness. In cabarets and in the café-concert, the asylum and its inhabitants were remade as spectacle, an image to be inhabited. What emerged was a distinctly modern way to interpret women and their bodies—uncontrollable, erotic, and a little mad.

Three days after Christmas, on December 28, 1882, Jeanne was admitted to the hospital. Her intake papers noted that she suffered from Saint Vitus’ dance, an epileptic disorder. In 1933 she published a memoir, describing her time at the hospital fifty years before as “fate!” By then the former patient, now known as Jane Avril, was eager to cement her relationship with the Salpêtrière, to prove that Jane La Folle was authentic and that her steps were true.

“I spent two years in this ‘Eden,’ ” Avril wrote in her memoir, “for it was one for me, inasmuch as everything in this world is relative.”

Avril might have been one of the few residents who thought of the Salpêtrière—a place described by Jean-Martin Charcot, its own head physician, as a “great emporium of human misery”—as paradise. The French media dubbed Charcot, who had overseen the hospital for nearly two decades by the time Avril arrived, the “Caesar of the Salpêtrière.” During his long tenure, he made invaluable contributions to the field of neurology and is still considered a pivotal figure in the field. He named and described aphasia, Parkinson’s, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, and Charcot’s disease, now known as ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, formerly called Lou Gehrig’s disease in the United States).

The history of neurology and its developments in the nineteenth century—the very foundations of the field’s contemporary knowledge—are inextricable from women like Avril. The bodies of the five thousand women at the Salpêtrière were what Charcot once boastfully described as “a reservoir of material,” a ready source of study and experimentation. Entry into Salpêtrière may have been free, but it came at a high price: their bodies were often the unwilling source of someone else’s knowledge.

It wasn’t just Charcot, though he was the main attraction. The Salpêtrière was a teaching hospital; doctors from across Europe flocked there, eager to work with the influential neurologist. The fields of neurology and psychiatry are littered with disorders that bear the names of Charcot’s most renowned students, including Georges Gilles de la Tourette and Pierre Janet. It was under Charcot’s tutelage that Sigmund Freud, young and addicted to cocaine, began to formulate his own theories about hysteria, theories that would eventually eclipse those of his teacher. Charcot’s renown might have initially brought these and other students to the Salpêtrière, but they also were particularly attracted to his reinvention of a disorder nearly as old as humanity itself: hysteria.

“Monsieur Charcot [has put his] finger on the wound of the day,” writer and critic Jules Claretie wrote in his 1880 book La vie à Paris. The Salpêtrière was home to thousands of women, with the vast majority suffering from epileptic disorders, petite hystérie, or hystérie ordinaire. But it was Charcot’s grand hysterics—those diagnosed with the far rarer la grande hystérie or l’hystérie épilepsie—who captured the public’s imagination. Avril called them the “stars of hysteria.” Blanche, Augustine, and Geneviève, the Salpêtrière’s most famous hysterics, had fits that resembled epileptic seizures. Novels romanticized the women, as in Claretie’s 1881 novel set in the Salpêtrière, Les Amours d’un interne.

The grand hysterics performed before an interested public during Charcot’s Tuesday lectures. His recorded observations of the women are practically picturesque, a lyrical, musical scene that encompasses the image and the movement of dance. Writing about a sixteen-year-old patient in his notes, Charcot observed that after applying pressure to her ovarian region, “rhythmic chorea breaks out.” (Chorea, from the Greek, simply means “dance.”) She remains conscious, but “her head begins suddenly to turn right to left, and then from left to right, in rhythmic alteration with equal pauses between the individual movements. Simultaneously, the right arm begins going up and down, as a result of which her right hand beats regularly on her knee as though on a drum. The movements of the hand are synchronized with those of the head. Meanwhile the right foot is stamping noisily on the floor.”

Even though Charcot could not entirely disentangle hysteria from a long history centering it in the womb, he did not consider hysteria a disease of the uterus. Instead, he theorized that it was neurological in origin, no different from any other epileptic disorder. (For much of his career, he believed he would locate a brain lesion that caused the disorder and thus treated both men and women for hysteria. It is telling, however, that his “stars” were all patients at the Salpêtrière rather than the men he treated in his private practice.) Without a visible organic source, la grande hystérie and l’hystérie épilepsie could be diagnosed—and subsequently interpreted—only via close observation. That required a wealth of images, particularly photographs, that could be studied. Charcot was an early adopter of the idea that photography could serve as a scientific and medical observation tool. The Georges Didi-Huberman wrote in Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière that Charcot transformed the Salpêtrière into an “image factory.” The hospital was equipped with a glass studio, a darkroom, and a range of props necessary to stage and capture a hysterical attack, including backdrops and a raised platform.

In the hospital’s studio, photographers Paul-Marie-Léon Regnard and Albert Londe obsessively documented women’s bodies. Londe pointed his nine-lens camera at patients to capture epileptic fits, while Regnard worked to capture the nuances of a hysterical attack. In Regnard’s 1878 book Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière, Augustine appears over and over again. Her body “jolts,” “cramps,” “quakes,” and “jumps.” It is never placid, never still, but always in the “throes” of excitement or passion.

In one particularly compelling photograph of Augustine taken by Regnard, she throws her head back, nearly bent in half, her spine in a dramatic arch, eyes open, in the middle of a cataleptic seizure. The Salpêtrière developed a number of techniques to induce catalepsy, a common symptom among Charcot’s hysterics—among them tuning forks, bright lights, a gong, and igniting nitrocellulose.

Compelled to move, either by their bodies or Charcot, these women performed an involuntary choreography, accompanied by explosions, music, and lights. Regnard recounted one session:

Six hysterics were placed in front of a camera, and I told them that they were going to have their portrait taken as a group. Suddenly there was a violent noise in the other room. The six patients made gestures of fear and were frozen in catalepsy...The camera was immediately opened.

The availability of the photographs produced at the Salpêtrière, combined with the titillation of Charcot’s Tuesday lecture, collapsed the boundaries between the hospital and polite society. The nervous pathologies described and defined there seeped into public consciousness. Novels romanticized the women, as in Claretie’s Les Amours d’un interne. But nowhere was that more apparent than at the Moulin Rouge and Paris’s cafe-cabarets in the 1890s, where the suggestive sexuality of Charcot’s spectacle was made plain.

Epileptic gestures and movements became a model for the cabaret and the café-concert. Gommeuses épileptiques (epileptic singers) took the stage and sang of the sexual appeal of women with limps and deformities, both considered hysterical symptoms. As historian Rae Beth Gordon has discovered, examples of the genre include the songs “The Limping Girl of the Regiment,” “The Little Limping Girl,” and, less coyly, “The Invalid.” “The nutty refrains are sung by subjects who indulge in spewing out the cries of the hysteric,” one nineteenth-century critic wrote.

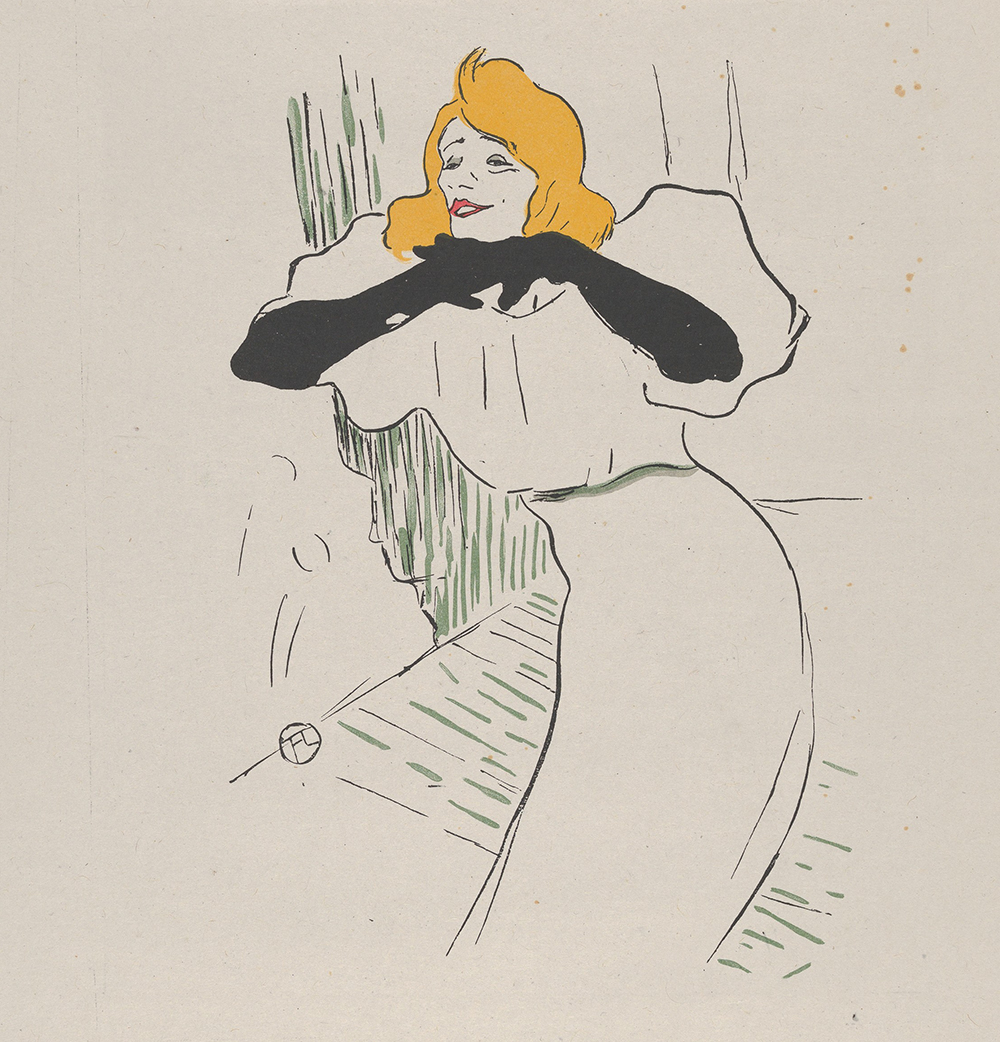

There wasn’t much linguistic space between the descriptions of the cabaret’s most beloved performers and Charcot’s descriptions of his les grandes hystériques. Performer and cabaret owner Marguerite Duclerc was renowned for her “tumultuous shaking and trembling” and her “audacious gestures,” according to contemporary descriptions. At the Café des Ambassadeurs, singer Emilie Bécat performed with wild gestures that evoked the patients of the Salpêtrière. A small work by Edgar Degas depicts Bécat with arms outstretched, standing before a rapt audience. And at the Moulin Rouge, Polaire, with her waist painfully corseted to sixteen inches, danced, in her words, with “clenched fists,” “toes twitching,” and “bent over backward as though cut in two by my flexible waist with nervous, exasperated movements.” Colette wrote that she “applauded” Polaire “in her epilepsy.” Polaire’s nervous movements were a stark contrast to the stillness of Yvette Guilbert, who emphasized her pallor and thinness, looking almost frozen in silhouettes that conjured a cataleptic attack.

Then there was Jane La Folle dancing the cancan. In their 1867 novel Manette Solomon, the Goncourt brothers described the Parisian cancan, similar to the one Avril danced, as “corrupted,” “the epileptic cancan that spits like a blasphemy.” Yet Avril’s interpretation was almost mournful. In an 1892 poem about her, the British writer Arthur Symons described her grace as “morbid,” “vague,” and “ambiguous.”

The feel of Avril’s epileptic cancan was captured by Lautrec in an 1892 painting not long after Avril debuted at the Moulin Rouge. She hikes up her white petticoats to reveal thin legs clad in her signature black stockings. Her left knee bent, foot lifted from the ground, ankles turned at impossible angles, expression engaged and face turned away, Avril looks thoroughly absorbed as she dances, seemingly unaware of any audience. Rendered in the bold strokes and frenetic dabs that typified Lautrec’s style, the painting captures the feverish feel of her steps. The floor’s green highlights practically dance off the painting. (Lautrec painted Avril many times throughout the 1890s until alcoholism and syphilis forced him to abandon Paris.)

Avril’s face is especially captivating, its frozen expression a contrast to her movement. Her face was one of her claims to authenticity—unlike that of her counterparts, her expression wasn’t an epileptic simulation. She never fully recovered from Saint Vitus’ Dance, which left half of her face frozen in a grimace.

For Avril, diagnosis was destiny. Named for a thirteen-year-old saint, a boy who cleaved to God as he was being tortured by his debauched Roman father in the early second century, Saint Vitus’ dance became associated with the dancing manias that appeared throughout Europe as early as the thirteenth century, when whole towns would find themselves unable to do anything other than succumb to choreography. After dance manias inexplicably disappeared, Saint Vitus became the patron saint of dancers, actors, and epileptics—a telling mix of afflictions.

Though men and women alike fell prey to the dancing manias, Saint Vitus’ dance was primarily associated with women. Their bodies, a nineteenth-century chronicler of dance manias noted, were more susceptible to the “sensual irritation” that produced the disorder.

For those who witnessed the manias, the particular look of a body captured by Saint Vitus must have been unforgettable. That involuntary, unnatural movement became so cemented in the minds of Europeans that the name stuck; the Swiss scientist Paracelsus dubbed the manias chorea Sancti Viti. After dance manias ended, Saint Vitus’ dance remained. In the mid-seventeenth century, the name was used interchangeably with Sydenham’s chorea, after the British physician Thomas Sydenham invoked Saint Vitus’ dance to describe the tic disorder that carries his name. Even though Sydenham’s chorea likely bears little resemblance to the fevered, obsessive look of earlier dance manias, both conditions expressed a particular idea of movement and became fused.

Jane La Folle continued after her cancan days as a series of different visual references, all of which pointed to hysteria. Long after her retirement, Avril was keen to cultivate her legend by embracing her time at the Salpêtrière while distancing herself from la grande hystérie. In her memoir, she disdained the “stars” of hysteria and their doctors. She mocked the “wise men” who were fooled by “madwomen whose illness, called ‘hysteria,’ consisted above all in its simulation.” “What lengths they went to in their efforts to seek attention and upstage the ‘star,’ ” she wrote.

Unlike Charcot’s hysterics, Avril was no actress. She claimed that she learned to dance at what might now seem like an unusual event: the Salpêtrière’s bal des folles, the annual madwoman’s ball. Though dances and other amusements, considered both diversion and treatment, were common occurrences at asylums in the nineteenth century, the bals des folles stoked the public’s interest almost as much as the tics at the Moulin Rouge. Like everything else at the Salpêtrière, it seemed designed for the purpose of spectacle. In a dress borrowed from Charcot’s daughter, Avril danced surrounded by hysterics and epileptics, in a deep reverie, barely noticing those around her. When she finished she found the entire hospital looking on, mesmerized by her dance, patients loudly applauding. “Alas, I was cured!” she wrote, transforming affliction into art.

It’s a fine story, one worthy of the actresses who feigned hysteria at the Salpêtrière and the Moulin Rouge. But it’s not true. Avril never attended the bal des folles, and she never borrowed a dress from Charcot’s daughter. She remained afflicted with Saint Vitus dance for the rest of her life, intermittently experiencing involuntary tics and twitches, and was institutionalized at the Sanatorium de Villepinte outside Paris in 1894, which remains unmentioned in her memoir.

By the time Avril sat down to write, she was sixty-five years old. She was impoverished and long forgotten, the stars of the Moulin Rouge and the Salpêtrière largely faded memories. Yet their influence lingered in art and film. The Surrealists used photographs of “delightful” Augustine in a 1928 issue of La Révolution Surréaliste in which André Breton and Louis Aragon described hysteria as the “greatest poetic invention of the end of the nineteenth century.” And the gestures of both the Salpêtrière and the gommeuses épileptique became a fixture of visual culture, particularly on the stage and in film. Sarah Bernhardt visited the Salpêtrière for inspiration, and, as Gordon notes, Maurice Chevalier was trained in the epileptic style, well known on the vaudeville circuit, and used a subdued form of its gestures well into his later film career. (Watch closely when he sings “Thank Heaven for Little Girls” in the 1958 film Gigi—his small hand movements are a remnant of the gommeuses épileptique.)

Charcot’s theory of hysteria had also faded, eclipsed by Freud. No longer was hysteria perceived to be an epileptic disorder—now it was the province of abused and traumatized women, a diagnosis carrying the stigma of mental illness.

But nearly half a century after Avril left the Salpêtrière, she couldn’t sever her ties with the teenager who showed up at the hospital’s gates, desperate for treatment. Jane La Folle was not just a fiction of the cabaret but a necessary creation. The choreography was, in Avril’s estimation, always involuntary, always a little mad. She wrote that perhaps dancing “is one of many forms of what is called madness. If so, for me it was always sweet and comforting. It helped me live.”