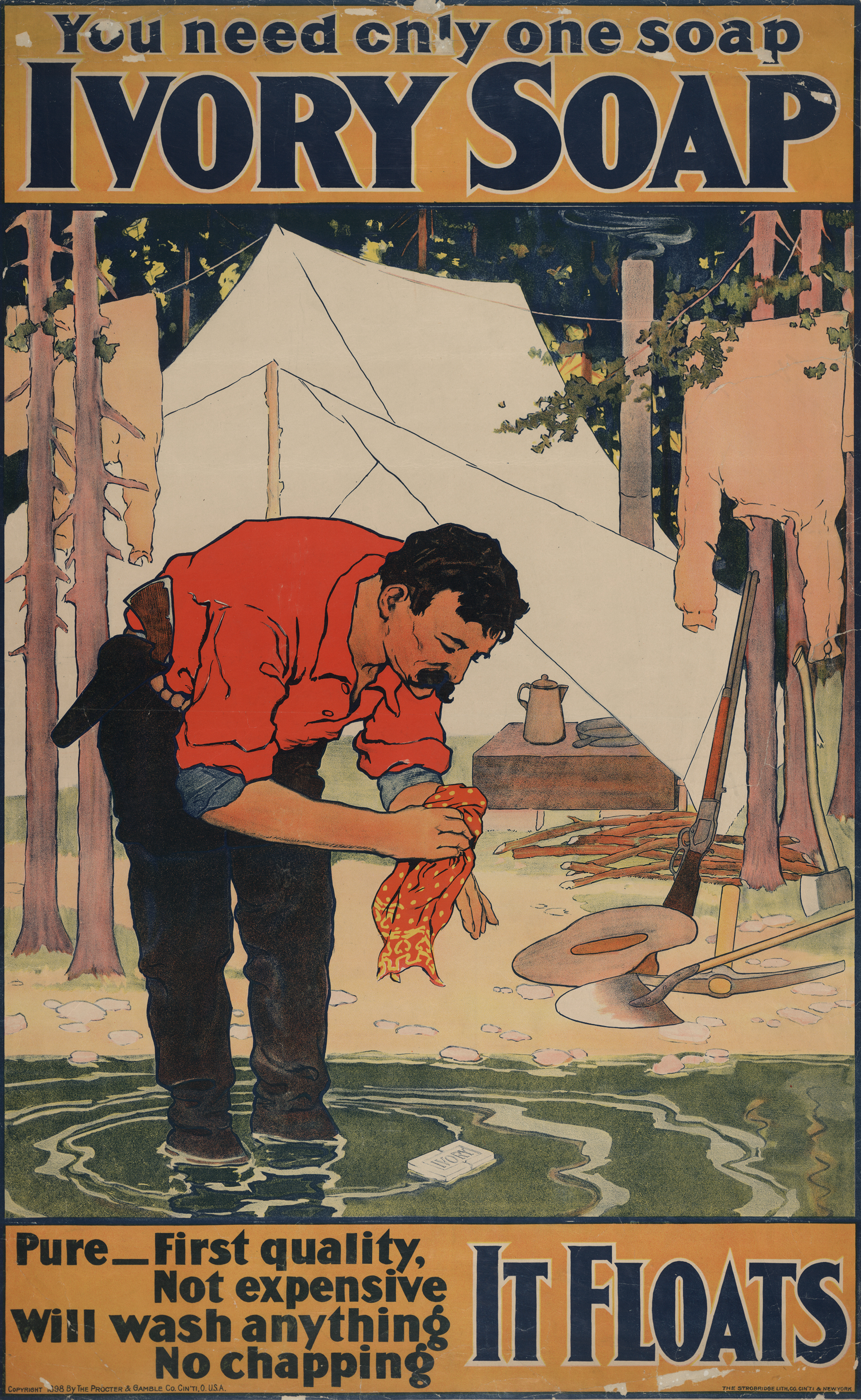

Ivory soap advertisement by the Strobridge Lithographing Company, c. 1898. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In his sweeping 1929 history of advertising from ancient Babylonia on, industry pioneer Frank Presbery waxed poetic about advertising as a progressive, rationalizing force. Properly deployed, advertising would not only evenly distribute earthly goods to the masses but would make knowledge universally available as well. “If everybody had all the knowledge that exists and is available, and applied it, there would be very little unhappiness,” Presbery concludes sunnily.

But American advertising—and cosmetic advertising in particular—traces its origins to the decidedly less-than-rational hodgepodge of science, magic, and faith that formed the culture of medicine and “wellness” in the late nineteenth century. The first efforts at national advertising were launched by patent-medicine manufacturers, whose elixirs, pills, drops, and ointments promised customers miraculous physical and mental transformations. For all of its purported down-to-earth rationality, the advertising industry had deep roots in magical thinking. This was a past it would never completely leave behind: that was, in fact, integral to its cultural success.

“Patent” medicines—so-called because in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England, one had to acquire a government license to peddle them—had a guaranteed place on every apothecary’s shelf in colonial America. Such English imports as Daffy’s Elixir, Dr. Bateman’s Pectoral Drops, and a specially patented “Oyl extracted from a Flinty Rock for the Cure of Rheumatick and Scorbutick and other Cases” were stocked side by side with the druggist’s more standard materia medica.

Nineteenth-century medicine lagged notably behind other scientific fields, with the average doctor’s practical knowledge barely advanced beyond the medical wisdom of the second-century Greek physician Galen. The average physician’s principal weapon for fighting illness—induced vomiting/diarrhea and copious bleeding of patients with lancets and leeches—remained of dubious aid. Those desperate to see themselves and their loved ones well were naturally tempted by alternative remedies.

Before the scientific revolution, science and magic—including the science of healing—were separated by only the finest of lines. Medicine men were stock characters at carnivals, markets, and fairs, peddling their cures alongside palm readers, acrobats, magicians, and animal trainers. Indeed, the pairing of “showmanship and dental surgery” was a bizarrely popular genre, spawning a number of dentist-puppeteers and dentist-acrobats who, presumably, found that, in the absence of anesthesia, their surgery went more smoothly when performed on distracted patients. They and their heirs attracted an audience as much for their entertainment value as for their medical adventuring.

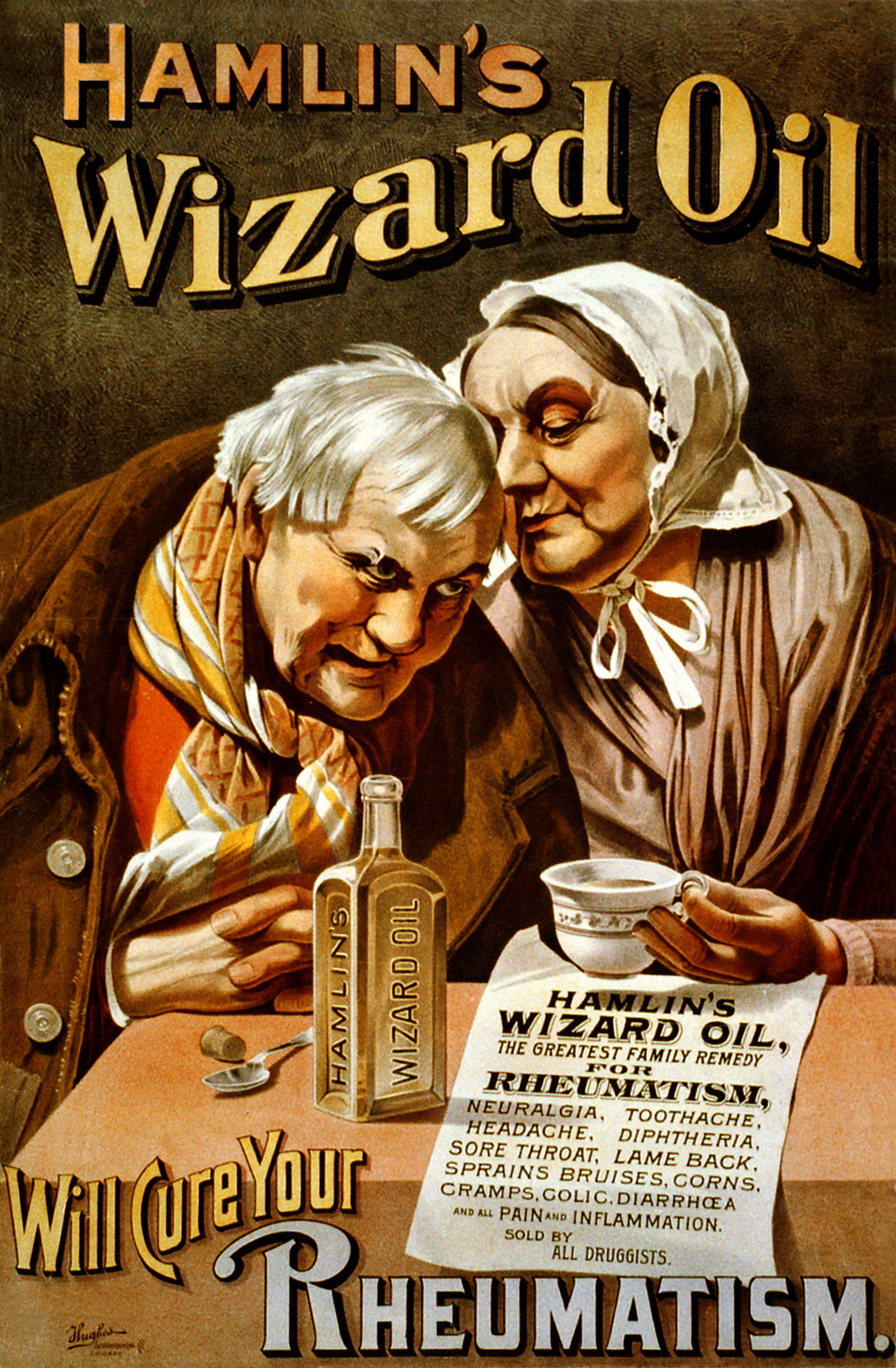

In this vein, nineteenth-century American patent-medicine manufacturers mounted elaborate “Medicine Shows,” sent out to travel the highways and byways of the country. The Wizard Oil Company, founded by magician John Hamlin, is illustrative of the genre, whose popularity peaked in the 1870s and ’80s. The Chicago-based company combined a canny modern distribution model with the ancient lure of spectacle: Hamlin sent out fleets of horse-drawn wagons, with colorful ads for Wizard Oil and equipped with a stage and parlor organ. The performers not only conducted open-air entertainments and point-of-service sales but stocked village pharmacies throughout the Midwest with bottles of Wizard liver pills, cough remedy, and liniment oil.

Despite the appeal of these theatrical extravaganzas, American patent-medicine manufacturers got their greatest boost from the rapid spread of literacy and print media in the nineteenth century. In 1800 the United States counted twenty daily newspapers; by 1860 that number had shot to four hundred, thanks in part to steam-powered presses and cheaper paper.

Patent-medicine companies were among the earliest and most cash-flush investors in the new advertising medium. True to form, patent-medicine print advertisements were flamboyant and theatrical. “There is no Sore it will Not Heal, No Pain it will not Subdue,” promised one newspaper advertisement for Hamlin’s Wizard Oil. “The Great Medical Wonder…Magical in its Effects,” the company assured health-conscious consumers. “The bones are sold with the beef,” sighed one small-town editor when readers objected to the quantity of advertising in the paper. He knew that without ad revenue, the paper would require a paid circulation of two thousand, rather than its current two hundred, to survive.

Nor did the patent-medicine companies confine themselves to newspaper ads. The introduction of photo engraving and chromolithography meant that advertisements and other printed promotional materials could be made more eye-catching. Medicine firms ran off handbills, pamphlets, posters, trade cards, and, perhaps most effective, almanacs. The traditional almanac was intended for use as a calendar, but it could also contain general reference material, horoscopes, recipes, and cartoons and jokes, making its annual publication something of a literary event. No other printed sources were issued in such large editions, with the possible exception of the Bible. While patent-medicine companies began by taking out ad space in popular almanacs, they soon realized printing and distributing their own almanacs provided better exposure. By the 1890s all of the major patent-medicine companies were distributing their own almanacs—replete, of course, with generous plugs for their healing remedies—free of charge to drugstores across the country.

Trade cards were another means by which advertising slipped, often unnoticed, into the American home. Indeed trade cards were, according to one historian’s estimate, the most ubiquitous form of advertising in America in the 1880s. These palm-sized three-by-five cards, engraved with the name and address of a product and an accompanying picture, created brand loyalty and a feeling of “ownership” in the customer. The fact that the pictures were printed in color was both a delight and a novelty to the average nineteenth-century reader, and the cards quickly spawned a collecting craze. Young women and girls in particular organized them into scrapbooks, cutting, pasting, and collaging the images into playful patterns, ads for tea, soap, shoes, and sewing thread side by side with plugs for Dr. Grosvenor’s Liveraid and Lydia Pinkham’s Female Vegetable Compound.

By the dawn of the twentieth century, there was no village so remote, no backwater so forsaken that the patent-medicine industry hadn’t penetrated it, spreading its garish, cheerful gospel of good health through mass mailings, trade cards in scrapbooks, almanacs piled high on drugstore counters, posters plastered on fences and billboards and barns. But the American unconscious had been primed, perhaps, for this riotous explosion of therapeutic messages by the religious fervor that had swept the country in the 1830s and ’40s. During the Second Great Awakening, revivalist preachers canvased the nation, holding forth in local pulpits and in open-air “camp meetings,” calling for believers to step forward and accept Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior. The promise of rebirth and spiritual rejuvenation through Christian faith overlapped with the rhetoric of medical “miracles” common among patent-medicine hawkers.

One minister who became alarmed at the carnivalesque aura attaching to religious revivals, John Fanning Watson, penned an 1819 pamphlet entitled Methodist Error; or, Friendly Christian Advice to Those Methodists, Who Indulge in Extravagant Emotions and Bodily Exercises. He warned readers that these “noisy Christians” prone to “falling down, jumping up, clapping hands, and screaming” were, far from bearing witness to the miracle of transformative grace, committing a “gross perversion of true religion.” The acrobatic dentist, banjo-strumming medicine salesman, and leaping Christian bore an uncanny family resemblance. All promised rejuvenated bodies and souls to an audience in search of health.

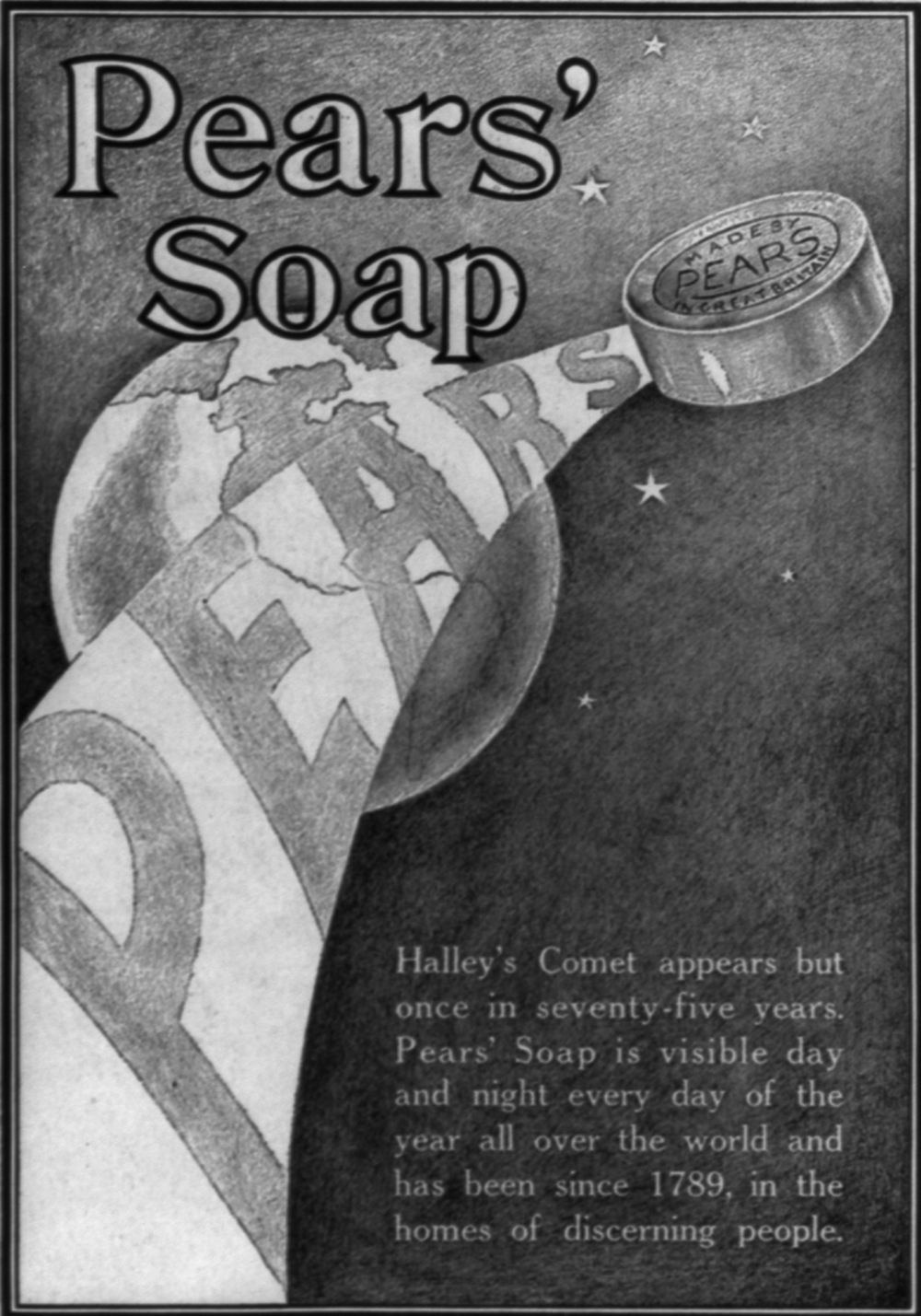

By 1885 no one thought it particularly odd that the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher should publicly endorse Pears’ Soap, announcing that “if Cleanliness is next to Godliness, then Soap must be considered as a Means of Grace.” Women’s magazines from the 1880s up through World War I featured advertisements for a wide variety of soaps, creams, and powders that were judged to be “skin improving” rather than skin covering or masking. In part, the rhetoric of cleanliness worked because it resonated with a wide range of “clean living” health and reform regimens that were popular in the nineteenth century, from hydropathy (water cure) to temperance to vegetarianism. These movements imagined the human body as a porous organism whose health depended on strict regulation of inputs and outputs, guarding against attack by toxins and foreign bodies. Hydrotherapy, which by the end of the century counted thousands of adherents and dozens of treatment centers nationwide, operated on the principle that cold water taken internally and applied externally conferred a host of health benefits. In his 1850 medical treatise Hydropathy for the People, Dr. William Horsell counseled daily vigorous cold-water sponge baths as of “the greatest value to persons suffering from gout…nervous irritability, or weakness of the skin, etc.” In our artificial state of civilization, Dr. Horsell clarified, we fear exposing the skin to the natural healing elements of air and water, instead keeping it jealously wrapped up. The result is that our “skins become clogged…until at length we get crusted over with a substance similar to Roman cement.” “Open pores” and a “vigorous skin” are essential to “complete restoration” of bodily health.

The water-cure mantra was echoed in cosmetic literature. The skin, Madame Bayard averred in The Art of Beauty, is among the most important of organs and the principal means for purifying our bodies. The pores exude daily “a multitude of useless, corrupted, and worn-out particles,” by which “the greater part of all the impurity of our bodies is removed.” Clogged pores result in “acidity and corruption of our juices,” she said, and are the “secret source” of disease. Partly in response to a contemporaneous push for sanitation reform, and tied to the spread of indoor plumbing, the market for soap exploded between 1890 and 1920. Soap ads, using water-cure rhetoric, routinely compared the skin to a living, breathing entity whose vigorous natural process of absorption and evacuation were impeded only at grave peril.

In the quest to differentiate themselves from competitors—as well as to drum up new markets—soap advertisements in the Ladies’ Home Journal during the 1910s and ’20s were keen to teach consumers that household soaps, for use with laundry and dishes, were not to be confused with toilet soaps. Jap Rose soap, for instance, advertised with the tagline “Give Nature a Chance!,” warning that the woman who used “opaque, sediment depositing” household soaps on her skin was asking for complexion trouble. Only “transparent” Jap Rose soap would “loosen impurities” and “let the air in.”

Ivory soap alone resisted product differentiation, marketing a single soap product for toilet, kitchen, and laundry but offering detailed instructions on how to use it in each context. Almost without exception, soap manufacturers crafted their advertisements around the principle that proper cleansing helped the skin and scalp perform its “natural” biological functions. With assiduous attention, the user’s inner beauty (and thus moral virtue) could be coaxed to shine through. Packer’s Tar Soap, for instance, promised that regular use would not only cleanse but “quicken the blood supply, increase the scalp’s nutrition, and thus aid nature in keeping your hair alive and beautiful.” Packer’s also claimed for itself the honor of being “first assistant of good Dr. Nature,” bringing “quickened life to your glands.” Woodbury’s and Pears’ soaps echoed this pseudoscientific, vitality-obsessed language. Beautiful hair starts with a “vigorous” scalp, they assert, since it is here that the nutrition-rich “network of blood vessels,” “fat glands,” and “color supply pigment cells” lie nestled. Stimulating massage plus lather plus water flushes out “dead cells” and “dust,” leaving “the pores clear and free to do their work.” In a stroke of off-label marketing genius, Sunkist citrus fruits even got in on the cleansing game. Sure, soap helped flush out sediment, but who was to say that soap wouldn’t itself become a kind of second-order sediment? Only the fresh-squeezed juice of a lemon, Sunkist offers helpfully, “cuts the alkali in the soap and leaves the hair really clean.”

Advertisements assured women that beautiful skin was democratic: it was not a luxury reserved for the few, those with a “naturally” good complexion. On the contrary, all women harbored potential inner beauty that simply had to be coaxed into expressing itself outwardly. “Nature intended your skin to be flawless,” announces a 1919 ad for Woodbury’s soap, noting that “skin specialists are tracing fewer and fewer troubles to the blood.” Instead, skin blemishes are the result of one “insidious and persistent enemy”: bacteria and parasites smuggled into the pores via atmospheric dirt, soot, and grime. It is up to the woman to keep a sharp watch over the proper evacuation of her pores.

Reprinted with permission from The Angel in the Marketplace: Adwoman Jean Wade Rindlaub and the Selling of America by Ellen Wayland-Smith, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2020 by Ellen Wayland-Smith. All rights reserved.