The Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, 2008. Photograph by Tipoune. Wikimedia Commons.

A crucial event in the history of mirrors took place in 1664 when the French “stole” the secret of glass mirrors from the Italians. Before this Venice was very much the capital of glass-mirror manufacturing. After Venetian artisans developed the technique of coating glass with an alloy of tin and mercury in 1507, Venetian mirrors became highly sought-after luxury goods coveted by European kings and queens. In 1664, however, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, treasurer to Louis XIV, secretly obtained this technique and brought it to France, ending the 150-year monopoly of Venetian mirrors in the industry.

In the following decades the French developed techniques enabling them to make glass mirrors in larger sizes and became the leader of the trade. Meanwhile in England, the Vauxhall factory founded by the Duke of Buckingham also employed Venetian craftsmen, using an amalgam of tin and mercury to make mirror-glass sheets up to one meter long. These developments ushered in a new era of interior design and furnishing, characterized by adorning wall surfaces with abundant shiny glass mirrors.

In France this development happened during the rule of the Sun King, Louis XIV. One of the most formidable monarchs in European history, Louis XIV was on the throne for seventy-two years, setting the record for the longest reign for any ruler in world history. During his fifty-four years of active rule from 1661 to 1715, what Voltaire called “le siécle de Louis XIV,” he turned French into the lingua franca among the European elites and made the French court the trendsetter of Europe. The Palace of Versailles, which Louis XIV exhausted the resources of the entire nation to build, elicited much envy and emulation among other monarchs after its completion in 1684.

Among Versailles’ many halls, the most talked about is the Hall of Mirrors. Its northern and southern walls, each seventy-five meters long, are divided into seventeen sections. On one side of the wall, seventeen grand vaulted windows look into the garden. The other side is covered with seventeen huge mirrors of the same shape and size as the opposite windows, thereby capturing the views seen through the transparent windows.

Information about this famous hall can be found in any tour brochure. The descriptions are usually mostly accurate except for one fine detail: each grand mirror is actually composed of twenty-one smaller mirrors—fifteen square ones in the main part, three curved ones on top, and three connective mirror strips between the main part and the top. The total mirror count in the Hall of Mirrors is thus in fact 357. Another misunderstanding about these mirrors is that their main function is to reflect the hall’s visitors, a misconception best illustrated by the fact that it is now filled every day by selfie-taking and Instagram-posting tourists. In fact, the seventeen composite mirrors were originally designed to reflect the view of the garden outside the window on the other side, therefore making the solid palatial walls “disappear.” It is more appropriate to understand them as “mirror windows” than as dressing mirrors.

Although it is almost impossible today to register this effect among the throngs of tourists in the hall, visitors during Louis XIV’s reign completely understood and appreciated the original design. J.B. de Monicart, after being arrested and thrown into a cell in the Bastille, fondly remembered the days when he was walking in the Hall of Mirrors. As he wrote in 1710, assuming the voice of the hall: “My ceiling and its contours seem to have little holding them up, for the high walls of mirrors and transparent panes appear as the only support for this large expanse, and yet these sections are all the better for letting me see the scenery within my view.”

It is worth reminding readers that in ancient China there were quite a few “halls of mirrors” as well, although unfortunately they survive only in textual records. The first one, recorded in the History of the Northern Qi, was commissioned by the last emperor of that dynasty (r. 565–77), who “erected a hall of mirrors, a hall of jewels, and a hall of tortoise shells in the consorts’ quarters. Decorated also with paintings and carvings, these buildings exhibited unsurpassable refinement.” Then there was Yang Jun (571–600), the prince of Qin and the third son of Emperor Wen of the Sui dynasty, who built an extravagant palace on a lake: “numerous mirrors, laced with pearls, were installed between the beams, pillars, doors, and windows, exhausting the extreme of extravagance.” This prince was a boy wonder who assumed the position of Great General at the tender age of twelve. Soon after, he acquired the additional titles of the Minister of Henan District, the Governor of Luozhou, and the Great Marshal General of the Guandong Army. But he became increasingly unbridled in his lavish lifestyle, dallying with his consorts and making merry with his guests day and night. This luxurious hall of mirrors was built precisely for such incessant festivities. Another hall of mirrors is recorded in Sima Guang’s (1019–1086) historical chronicle, The Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance. It relates that Pei Feishu, an official during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of the Tang (r. 649–83), erected such a building for the emperor in the palace district. One day Gaozong took Chief Minister Liu Rengui to see it as a special favor. But upon a glimpse of its interior Liu ran out. When asked why, he replied, “There are no two suns in the sky, and there are never two lords on earth. But in this palace Your Majesty’s images are scattered everywhere, which cannot be a good omen.” Alarmed, Gaozong had all the mirrors immediately dismantled.

This last record is especially interesting because, on the one hand, it seems to suggest a universal love for “mirror halls” among rulers east and west; yet on the other, while Louis XIV’s mirror hall was taken as an epitome of glamour and a symbol of power, which attracted much admiration in Europe, its Chinese counterpart elicited moral unease and drew criticism from an upright minister, which in turn generated political anxiety in the emperor himself.

It was Europeans who produced the first generations of large glass mirrors. Soon after France obtained the glass-mirror technology from Italy, Abraham Thévart, a glassworks manufacturer in Saint-Germain in Paris, showed a keen interest in making mirrors of an unprecedented scale and succeeded in producing glass mirrors nearly 1.5 meters long by the late 1680s. But manufacturing mirrors this large was still a trying business at the time. An architect by the name of Mansart wrote,

Since 1688 when large glass mirrors were invented, we have only managed to make three from 80 to 84 inches high and 40 to 47 inches wide that are still in one piece. Although a total of more than four hundred were produced, most of them were thrown back to be melted down and the rest are salvaged for pieces between 40 and 60 inches in height.

But the technology developed by leaps and bounds. An English traveler to Paris, Martin Lister, visited the Faubourg Saint-Antoine Glassworks in 1699 and wrote: “There I saw, fully complete and silvered, a mirror measuring 88 by 48 inches and only one-quarter-inch thick. I don’t think anyone could obtain such dimensions by blowing.” These large mirrors were made by casting, a new technique invented by Bernard Perrort in 1687. A carefully guarded trade secret, it was finally publicized, albeit partially, in a book titled Spectacle de la nature by a French priest, the Abbé Pluche. According to Pluche’s notes, the manufacture of large cast mirrors went through five stages: the building of the kilns and crucibles, the pouring, the flattening, the refiring, and, finally, the silvering, all demanding meticulous training before one could master them. The kilns needed to be rebuilt every several months. The crucibles were made with a special clay that could withstand direct firing up to a temperature of 1,800 degrees Celsius. In order to avoid the tiniest cracks, each crucible needed to be baked dry at a low temperature for several months, even though they could only be used for a maximum of three months before being discarded. During the stage of pouring, the workers made a mixture of sand and soda and melted it into molten glass. Next the workers poured the glass across the metal table and used a cast-iron roller to even the thickness of the sheet of glass. Finally the poured glass was refired to prevent it from shattering with use: the glass sheets were reintroduced into a large kiln called a carcaise, where they remained for three days, cooling in gradual stages.

The glass sheets were then turned into mirrors through the process of polishing, buffing, and silvering. Since these were all done in the city of Paris, untreated glass sheets were transported to Paris from Saint-Gobain. The polishing was done by placing wet sand between two glass sheets. Workers would rub the two sheets against each other, back and forth, for several days. The buffing process involved rubbing the glass with very fine iron oxide powder until the glass surface obtained its shine and transparency. The last step was silvering, for which workers pounded sheets of tin with a roller and stretched them out to less than a quarter of a centimeter thick, before spreading them out and rubbing them with a chamois cloth soaked in quicksilver. Then the tin sheets were submerged in quicksilver, and the glass was placed on top with great pressure so as to expel any air bubbles. For a day and a night, a heavy weight was placed on top of it. After this the assembly was gradually elevated on one end to drain off excess mercury. The mirror would still have to rest for another fifteen to twenty days for the amalgam to stabilize before it was ready for sale.

As the technique matured, the price of mirrors fell. While in the early eighteenth century a glass mirror measuring 180 x 100 centimeters could sell for £750 and a specimen measuring 230 x 115 centimeters could fetch the astronomical price of £3,000, by 1734 a mirror of the former size cost no more than £425, almost half what it was three decades prior. The price decrease resulted in the popularization of large mirrors among the households of the upper class: the sales of Saint-Gobain doubled between 1745 and 1755, and large glass mirrors became a necessity in the daily lives of the rich.

As the rich flaunted their wealth by showing off the glistening mirrors on the walls of their salons and parlors, these mirrors also fired up their passion for fanciful space—it was, after all, the age of rococo. As in Versailles, grand wall mirrors in any mansion offered endless reflections of the surroundings. They were installed not principally to inspect the appearance of host and visitors but rather to expand the confined spaces and to optically replicate, endlessly, the dazzling chandeliers and gilded armoires. It was precisely this ability to replicate reflections, which neither painting nor tapestry could achieve, that made glass mirrors the premier interior decoration of the time. As evidence, Germain Brice put mirrors at the very top of the list of architectural decor in his authoritative guide to high society’s fashion and taste, Description de la ville de Paris. Providing imaginary tours of the most beautiful houses in Paris, this book was reprinted twelve times between 1684 and 1752. Among the most fashionable trendsetters mentioned in the book, two stylish gentlemen renovated their houses with every unique and beautiful object imaginable, especially many grand mirrors in tortoise frames. This fashion was certainly not limited to Paris: when Madeleine de Scudéry described an ideal country chateau in her 1667 novel Mathilde, she likewise had grand mirrors installed opposite the windows so as to expand the natural views and open up the house.

As scholar Sabine Melchior-Bonnet observes,

The aristocratic society of Louis XIV had a passion for mirrors. Associated with light—the seventeenth century emphasized the optical and visual—mirrors lit up dark rooms, lightened thick walls, simulated window frames, and resembled precious jewelry in their elegant gem-encrusted box frames. When placed opposite windows, they reflected the scenery of the countryside and served as paintings, perfectly adapted to the subtle alliance of art and nature called for by the social proprieties of the time.

This “mirror fever” lasted about a century. Though new shapes and styles of framing appeared constantly, wall mirrors remained a perennial staple, often installed between windows as trompe l’oeils to confound real and fantasy spaces.

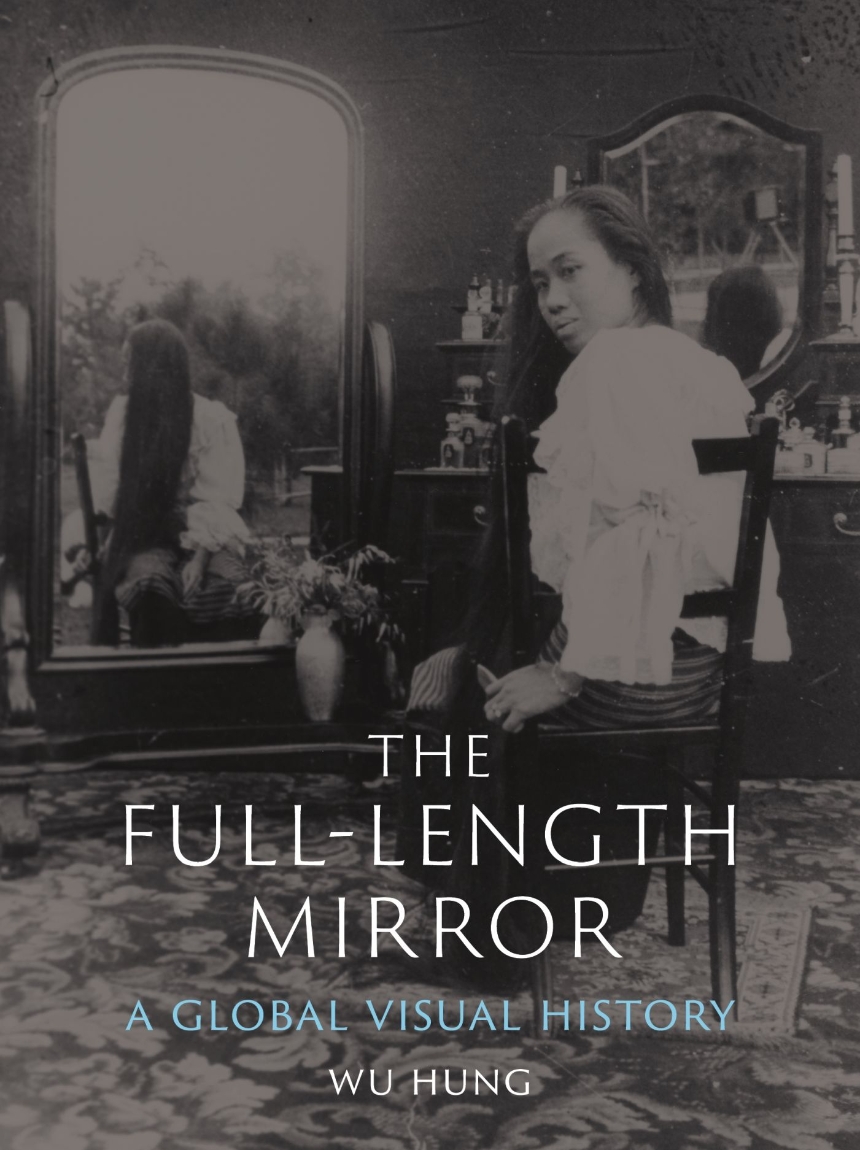

Reprinted with permission from The Full-Length Mirror: A Global Visual History by Wu Hung, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © Wu Hung 2022. All rights reserved.