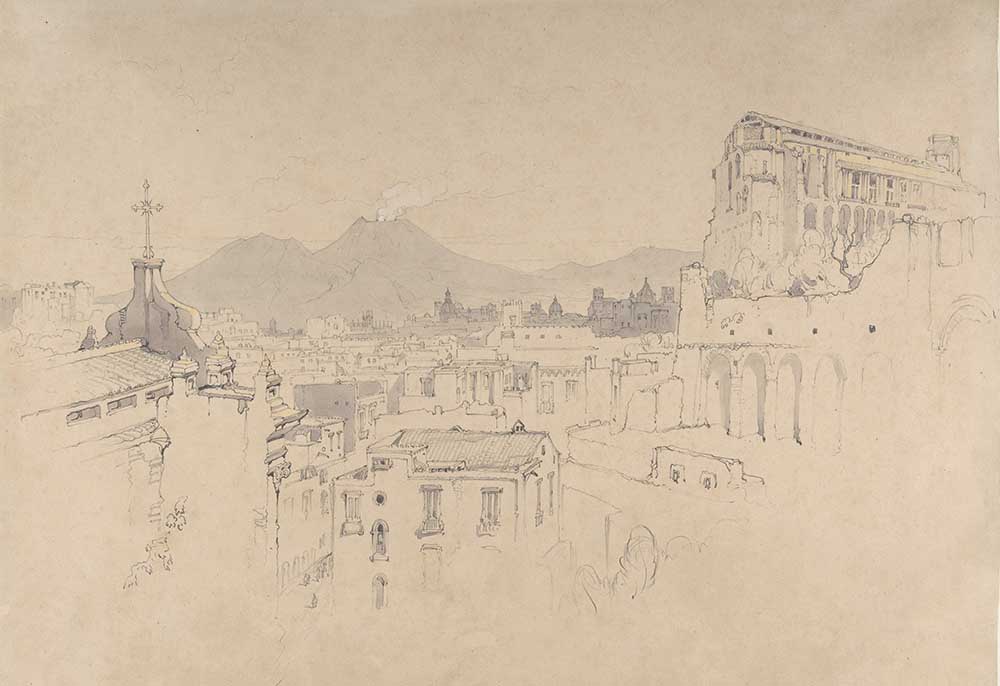

Natural Bridge, Sorrento, by William Stanley Haseltine, 1856. The Cleveland Museum of Art, gift of Helen Haseltine Plowden.

In March 1850 Alexis de Tocqueville developed the first overt symptoms of the tuberculosis that was to kill him nine years later. Writing to poet and politician Richard Monckton Milnes from Paris in April he informed him that “for the last six months our house has been a veritable place of misery. When the wife recovers, the husband falls ill, and thus it continues.” And so it was that Tocqueville applied for leave of absence for six months from his parliamentary duties and that he returned to convalesce in Tocqueville. If, despite his initial concerns, the long journey from Paris to Normandy had no adverse consequences (the sea between Le Havre and Cherbourg, Tocqueville recorded, was “a little choppy” but, for once, with no ill effect on his stomach), by early July he could report to politician Francisque de Corcelle that, although not fully recovered, his health was improving. A month later he told Corcelle that he was “visibly returning to the condition he was in before the spitting of blood.”

Yet, as was repeatedly to prove to be the case, Tocqueville’s optimism and his trust in his doctors was misplaced. A particularly exhausting early September—when Tocqueville had travelled to Cherbourg to attend a state visit by Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, and where he was obliged to make a speech—left him feeling weaker than he had been since his return to Normandy and, as winter approached, he became increasingly nervous about the consequences for his health of the inclement climate of the Cotentin Peninsula. Already, by early August, Gustave de Beaumont, the Democracy in America author’s frequent travel companion, was recommending that Tocqueville should follow the sun, wintering in Nice or possibly Algiers, Seville, Malaga, or Madeira, but a visit to see his doctor in Paris in October convinced Tocqueville that he should head for Naples or Sicily, returning to France in the spring.

Tocqueville and his wife (and their cook) left Paris at the end of October. The following day he wrote to Corcelle from Dijon. “Although,” he commented, “I have a very pronounced, if not a passionate, taste for travel, I begin this trip only with a certain nervousness and a heavy heart.” His plan, he told Corcelle, was to stay in the place with the best climate, probably Palermo. The chances were, Tocqueville decided, that little good or enjoyment would come from this trip.

To Beaumont, Tocqueville announced that he and Mary intended to take the packet boat from Marseilles to Civitavecchia via Genoa and Livorno and then travel overland to Rome and on to Naples (the latter, Tocqueville added, suited him better than travel by sea). However, on the expected day of their departure, the mistral began to blow, and the sea turned rough. So, fearing a bad crossing, departure was postponed to the following day. Buoyed by the knowledge that the boat Tocqueville and his wife were now to take was better and faster than the one they had originally intended to board and that fine weather looked to be in store for the next three days, they duly set off on November 11.

All went well until they were delayed in Genoa. News that quarantine restrictions had been lifted in Naples meant that their very small ship was inundated by a “multitude of English families.” One could not imagine such a crowd of people, he told Beaumont. The bridge and saloon were so full that he and his wife could hardly move. Worse was to follow. Between Livorno and Civitavecchia, and at night, they were hit by violent winds. The deck was awash.

“Men, women, and children,” Tocqueville continued, “took refuge in any way they could in the saloon, pressed together like slaves on a slave ship.” So many people were piled on the stairs that it was impossible to get out. “Add to this,” Tocqueville wrote, “that everyone was seasick, and you can guess at the awfulness and devastation.” The worst of it was that, in these crowded conditions, Tocqueville feared that he might suffocate. Fortunately, he was able to open a nearby skylight which, although it meant that he got drenched, allowed him, as Tocqueville put it, to survive. This “at the time was the only thing that mattered.” When they docked the following day, the storm had calmed, the disembarking passengers looking as if they came from “another world.” Poor Madame de Tocqueville had such horrible memories of their journey, Tocqueville told Beaumont, that he could not see her wishing to go to sea again for many months, if at all. So, after a day’s respite, they set out from Civitavecchia to Rome, where they stayed for only one night. Had he stayed longer, Tocqueville explained, he would have been obliged to see the pope and others with whom he had been in contact whilst foreign minister but equally he would have found himself again in the world of politics and of the kind that “pleased [him] the least.” Tocqueville and his wife thus arrived in Naples on November 21. Things hardly got better. He reported to Beaumont on November 24 that since their arrival they had had “strong winds, rain, hailstorms, and thunder.” Four days later he told Corcelle that he and his wife were not entirely over the tribulations of their sea crossing, adding that, with the exception of two beautiful days, the weather had been awful, the sirocco wind blowing with an “extreme violence.” In such circumstances, Tocqueville reported, the Mediterranean was not a pretty sight.

Yet the poor weather was as nothing compared with the displeasure Tocqueville felt at what he saw all around him. Italy, he told Beaumont, was “incomparably beautiful,” but what a people, “what unimaginable filth, what rags and tatters, what vermin.” One would have to go, Tocqueville continued, to the “most ghastly streets of Algiers to find something as foul as what one sees at every moment in the streets of Naples.” “I believe,” he wrote, “that the great party of order here in Naples contains a greater disinterestedness than ours, but, on the other hand, it has to be agreed that ours has a lot fewer lice.” The only well-dressed people were priests and soldiers.

Tocqueville’s description of political realities in Italy was equally scathing. To Corcelle (whom Tocqueville had appointed to a position at the Vatican when Tocqueville had been foreign minister) he wrote as follows: “A few revolutionary elements half destroyed, no liberal opinion, the restriction of all conceivable liberties combined with the mockery of a free constitution in which no one believes, a king who continues to die of fear although there is no cause to be frightened and whose cowardice turns a natural softness into tyranny, five or six thousand people detained without trial, and a completely happy people in the midst of all this squalor: there, it seems to me, is a reasonably accurate picture of this country.” Only five days later Tocqueville added to this litany of national misfortune in a letter to Beaumont. “In the whole dictionary of the French language,” he wrote, “I cannot find words which adequately express the pity and contempt that this miserable people and, even more so, these miserable Italian governments inspire in me.” Here were governments which did not even know how to make use of the despotism they adored, which used the resources of the country only to procure soldiers, and whose soldiers stupidly suppressed good as well as bad passions.

To his friend Madame de Circourt, Tocqueville confided that he did not reproach “these miserable little Italian princes” for not wanting constitutional government as their peoples were hardly in a condition to accommodate such a regime but he did reproach them for “understanding so badly the profession of despot” and for misusing it as foolishly and stupidly as their subjects did their liberty. Tocqueville told politician Victor Lanjuinais, was “easily the most unpleasant country that I have ever visited on my travels.”

Tocqueville’s letters to Corcelle and Beaumont also show that, as had been the case many times in the past, he was missing his friends and family in France. “It is,” he wrote to Beaumont, “a great and precious thing to have a true friendship like ours.” To Corcelle he confided that the distance from friends was made worse by the time it took for letters to arrive and for replies to be received. He was also finding their accommodation in Naples ruinously expensive. One thing was instantly apparent. Any plans to travel south to Sicily had to be abandoned due to Madame de Tocqueville’s unwillingness to endure another sea crossing.

Thus, waiting upon the advice of the historian and philologist Jean-Jacques Ampère, Tocqueville and his wife resolved to rent a house in Sorrento, just south of Naples, where, he had learned, furnished properties could be found fairly cheaply. The ever-cautious Beaumont was not convinced of the merits of the Sorrento climate in winter, warning Tocqueville on hearsay that it would likely be colder than Palermo or even Pisa and Nice and advising him that someone with respiratory problems ought not to go too often to the sea; but, as is evident from the accounts received by all his friends in France, Tocqueville was more than pleased with what they had found in their new accommodation at the Belvedere Guerracino. “I am writing to you,” he told his friend Eugène Stoffels at the end of December, “from a little town situated on one of the edges of the bay of Naples, opposite the city and Vesuvius.” One could not imagine, Tocqueville continued, “a more delicious region” or, up to now, “a milder climate.” The palazzo they had rented was surrounded by olive and orange trees on a hill looking out over the sea. To his cousin Louis de Kergorlay he wrote that “the location is charming, the house in which we live very well positioned, very well furnished, and, in sum, infinitely agreeable.” There were also walks beyond number.

There was, of course, something very different about this journey abroad from all the others that Tocqueville had made thus far. When Tocqueville travelled to America, to Algeria, to England and Ireland, he did so primarily to study aspects of that country, be it prisons, the poor law, the system of colonial administration, and so on. Upon this occasion, as Tocqueville told lawyer Paul Clamorgan, he was in southern Italy with one purpose in mind: to recover his health. Moreover, from what Tocqueville was quick to tell his friends, this seemed to be working. On December 30, he told Stoffels that he was in “excellent” health and so much so that he hoped that when he returned to Paris he would do so with the strength to resume an active public life. On the same day Tocqueville penned a similar message to Madame de Circourt, commenting that the wonderful climate was having a better impact than he had dared hope for.

Beaumont received similar news: already, Tocqueville wrote, he could feel the beneficial effects of the “admirable” climate and again he expressed the hope that when he returned to Paris in the spring it would be with “a restored health” and feeling stronger than he did before falling ill. Tocqueville wrote again to Beaumont in early January 1851, reporting this time that he and his wife “continue to be enchanted by [their] stay.” Madame de Tocqueville, it was true, had been ill with “her usual problems,” and Tocqueville’s stomach had not always been behaving itself, but these “crises” were rare and short-lived; what mattered was that his lungs were fine and he did not hesitate, therefore, to tell Beaumont that he was “in good health.” Nor, it might be added, did Tocqueville hesitate from telling Beaumont that what he had heard about the “freshness” of the Sorrento climate was mistaken. “Never,” he wrote, “have I seen in France a month of May as continually warm and beautiful as the month of December that has just come to a close.” All that was missing was what Tocqueville described as “the poetry of May, the energetic return of all beings to life and the universal awakening of nature.” Not once, he announced proudly, had the night temperature dropped below six degrees centigrade.

If the climate greatly pleased Tocqueville, so did the peace and quiet that he and his wife were enjoying in Sorrento. He told Madame de Circourt that he was living like a hermit. To this he added that he now realized that he preferred living with books rather than with their authors. The former, as opposed to the latter, had “no need to speak about themselves and not the least regret in hearing good said about others.” What was more, they could be put down and taken up as one wished. In a letter to one of his many English correspondents, Mrs. Rosalind Phillimore, Tocqueville remarked that he was spending his time with people from past centuries rather than from the nineteenth century.

To Beaumont, he explained that, since their arrival, he and his wife had been living in “complete solitude.” “We feel the desire for company,” he wrote, “but not the need of it, since our isolation does not weigh heavily upon us.” Likewise, Tocqueville told his brother Édouard that he was far from certain that he missed the company of others and even less certain that they were “suffering from not having it.”

Excerpted from Travels with Tocqueville Beyond America by Jeremy Jennings, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2023 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.