The Sick Child, by Gabriël Metsu, c. 1665. Rijksmuseum.

Beckett’s relationship with his mother, as with his Mother Country, was close and combative. May was a formidable woman, and however far he traveled, he never escaped her. The shadow of her presence looms in many of his deeply if obscurely autobiographical plays, poems, and novels, and he discusses his difficulties with her in letters to his closest friends. When he was twenty-seven, at the beginning of his professional writing life, he committed himself to intensive psychoanalysis in London (paid for by her) in an effort to come to terms with their embattled relationship, which was making him physically ill. But he remained inextricably involved with her, responded to her demands over the years (despite the advice of his analyst), and he attended her in her last illness in the Merrion Nursing Home by the Grand Canal in Dublin, though he had long been resident abroad. He sat (as he recalled in Krapp’s Last Tape) on a bench by the weir, gazing at her bedroom window, “in the biting wind, wishing she were gone…the blind went down, one of those dirty brown roller affairs, throwing a ball for a little white dog, as chance would have it. I happened to look up and there it was. All over and done with at last.” She died on August 25, 1950, having survived her husband Bill by sixteen years.

In October 1923, aged seventeen, Sam Beckett entered Trinity College Dublin to study English, French, and Italian, moving on after graduating with distinction to teach briefly in Belfast, then to Paris, where he became a lecteur d’anglais at the École Normale Supérieure, a position of prestige.

All seemed to be going according to plan, and Sam seemed set for a successful career as a scholar and academic. We do not know if May suffered from what we now call the empty-nest syndrome, or whether she was content with her life of visits and church activities and gardening in Foxrock, a leafy suburb of Dublin. Later evidence suggests that she would not have been happy for him to have settled permanently in Paris (and not at all pleased to learn that he had become friendly there with the notorious Irish exile James Joyce, who was already influencing Beckett’s prose, behavior, and aspirations). She wanted him nearer home, back in Ireland, where she could have some control over him. And he came back in 1930, to a post as a lecturer to Trinity College.

He returned from Paris looking skinny and in his own word “scrofulous,” and was welcomed home by his parents, who fussed over him and tried to fatten him up. He moved as soon as he could from Cooldrinagh, the house where he was born, to rooms at Trinity, where he was able to lead a freer and more bohemian life. But he returned to Foxrock in the summer to recover from a bout of pleurisy, and while he was there May happened upon some of his writing that he had left lying about, was (predictably) disgusted by it, and kicked him out of the house. It is not known which of his works-in-progress she came upon, but there are many possibilities of obscenity and blasphemy that would have caused extreme offense. In fact, there was hardly anything he wrote that she might have found acceptable. Did he leave it, whatever it was, lying around on purpose? Maybe his analyst was to ask him this question. The quarrel seems to have lasted for months, and he appears to have been as much upset by it as she was.

He was not happy teaching at Trinity, although he had good friends around him. He was not happy in Ireland. He knew he needed to get away.

He decided with much agonizing to ditch his career at Trinity, and resigned formally (by telegram) in January 1932, after heading off for Germany. Several years of often lonely wandering on the continent and in England followed, during which he worked on his fiction and on translations, made efforts to publish, made contacts in the literary world, and intensified his friendship with Joyce and (unhappily) with Joyce’s daughter Lucia. Back in Foxrock, May waited. After his sickly reappearance in 1930, maybe she suspected that ill health and poverty would bring him back. And eventually he gave in. After miserable months in London, he wrote to his parents asking for his airfare home, and “crawled home” with his tail between his legs. He tried to readjust to Cooldrinagh, playing the piano, sawing logs, and taking long walks with his father, which he always enjoyed, while he continued to work at his creative writing. But he was ill at ease in the Dublin he had tried to desert, and physically unwell. He was admitted to the Merrion Nursing Home in December 1932 for an operation on a cyst on his neck and on a hammertoe. His parents and brother, laden with books, visited him regularly. He was slow to recover and the operation on his neck did not heal well. May fussed over him and worried about him, with some reason. In May 1933 the cyst was lanced again, and May and Bill devoted themselves to trying to nurse him back to health, but he was frustrated and angry and started to drink more heavily. Both Bill and May were anxious for their son to take a “proper job,” for he was financially completely dependent on them, and on loans from Frank. (Sam’s relationship with Frank bears some resemblance to James Joyce’s with his brother Stanislaus: both writers were greatly in debt to their hard-working, more prosaic brothers.)

Beckett might have regained his health, and he might have come to consider more seriously one of the academic posts which had been dangled before him, but in June 1933, catastrophically, Bill suffered two massive heart attacks, and died. This was a disaster for both sons and mother. The obedient Frank, who had at one time tried to escape, was trapped forever in the family firm, and May went into deep and ostentatious mourning, which, much as he had loved his father, got on Sam’s nerves and drove him to distraction. He protested against “the vile worms of melancholy observance” and his health now got worse and worse, his supposed convalescence deteriorating into night sweats and panic attacks, insomnia and urinary problems. A doctor friend, Geoffrey Thompson, advised him to seek psychoanalysis, then illegal in Ireland, and somehow he persuaded his mother (on whom he was now financially dependent) to allow him to move to London and to sign on with Dr. Wilfred Ruprecht Bion (1897–1979), practicing at the Tavistock Clinic, and then at the beginning of what was to be a highly distinguished career. He started on January 27, 1934, and nearly two years of treatment followed, which seems to have focused largely on his relationship with May, who had both cossetted and constricted him all his life. Bion and Beckett were intellectually compatible, and got on well socially as well as in their analytic relationship. The London years were often painfully lonely for Beckett, but they were also productive.

He was also beginning to make progress as a writer. From May’s point of view, it was unfortunate that the very titles of his first two published works were so unlikely to be well received in Foxrock. This was not yet the successful author son of whom she could be proud. His poem “Whoroscope,” written and published in Paris in 1930, was ripely blasphemous and obscene, and his volume of stories, More Pricks Than Kicks, published by Chatto and Windus in 1934, was not the kind of volume to display prominently on the library shelves at Cooldrinagh. It even upset his liberal-minded and artistic Aunt Cissie, although she eventually came round to it. But the battle for recognition and acceptance from May continued.

However, in the summer of 1935, a most extraordinary interlude in their relationship occurred. Sam, still based in London, invited his mother to accompany him on a three-week holiday in England, an episode the strangeness of which has in my view not been sufficiently registered. It is true that she paid for everything, but he seems to have gone along with the plan willingly enough. He hired a car, prone though he was to motoring and cycling misadventures, and drove her to various cathedral cities (including St. Albans, Canterbury, Winchester, Bath, and Wells, an itinerary which involved covering many hundreds of miles) and on to the West Country, spending several days in West Somerset and North Devon. This is a long time to spend alone with a difficult widowed mother, and one doubts if Bion would have recommended it. But Beckett was enthusiastic about their sightseeing, and seems to have been able to enjoy himself. These travels strike me all the more forcefully because I know this part of the West Country very well, and am writing these words at Porlock Weir, overlooking the Bristol Channel, and a few minutes’ walk from the Anchor Hotel where the Becketts must have stayed. I know what he called “the demented gradients” of Porlock Hill all too well, and am surprised (as was he) that his hired car survived them. In Lynmouth, a few miles west of Porlock, they stayed in the Glen Lyn hotel, and followed in the footsteps of Shelley, Wordsworth, and Coleridge.

Beckett returned to London refreshed, having visited Lichfield by himself after leaving May with family (including a “loathed cousin”) at Newark, and with a new Lichfield-inspired idea in his head: he thought he might write a play about the melancholic and troubled Samuel Johnson, famous son of Lichfield. But instead he immersed himself in the creation of what was to be his first major novel, Murphy, set in London, and much of it closely based on his exhausting solitary tramps around the capital and his hours of study in its libraries. He worked and walked obsessively in what he described as a “boiling over,” while continuing to correspond regularly with May. But at the end of the year, in December 1935, he found himself back at Cooldrinagh, ostensibly for his annual Christmas visit, at the end of his analysis, and he stayed there in a truce that lasted for some months. He was suffering from pleurisy, and May was delighted to devote herself once more to nursing him. They rubbed along together as best they could. She kept him, in his view, short of money, and urged him to seek what she reasonably called “gainful employment.” One can see her point of view. He had excellent academic qualifications, and had carelessly thrown away his appointment at Trinity College. But he thought the world owed him a living. He seemed to expect to live off her forever, drinking with his friends in town or hiding in his study writing books she would never want to be seen reading.

Luckily for both of them, some ill-judged and doomed sexual attachments convinced him that he had to get away from Dublin again, and in September 1936 he set off for Germany after what his biographer James Knowlson described as “a tense, though fond farewell to his mother on the front porch of Cooldrinagh.” She was glad that he was getting away from the two unsuitable young women with whom he had been involved, but she had little faith in his future. He could now expect a small annuity from his father’s estate, but it would not be enough to support him. She cannot yet have had any intimation that he would become self-sufficient, successful, and world famous.

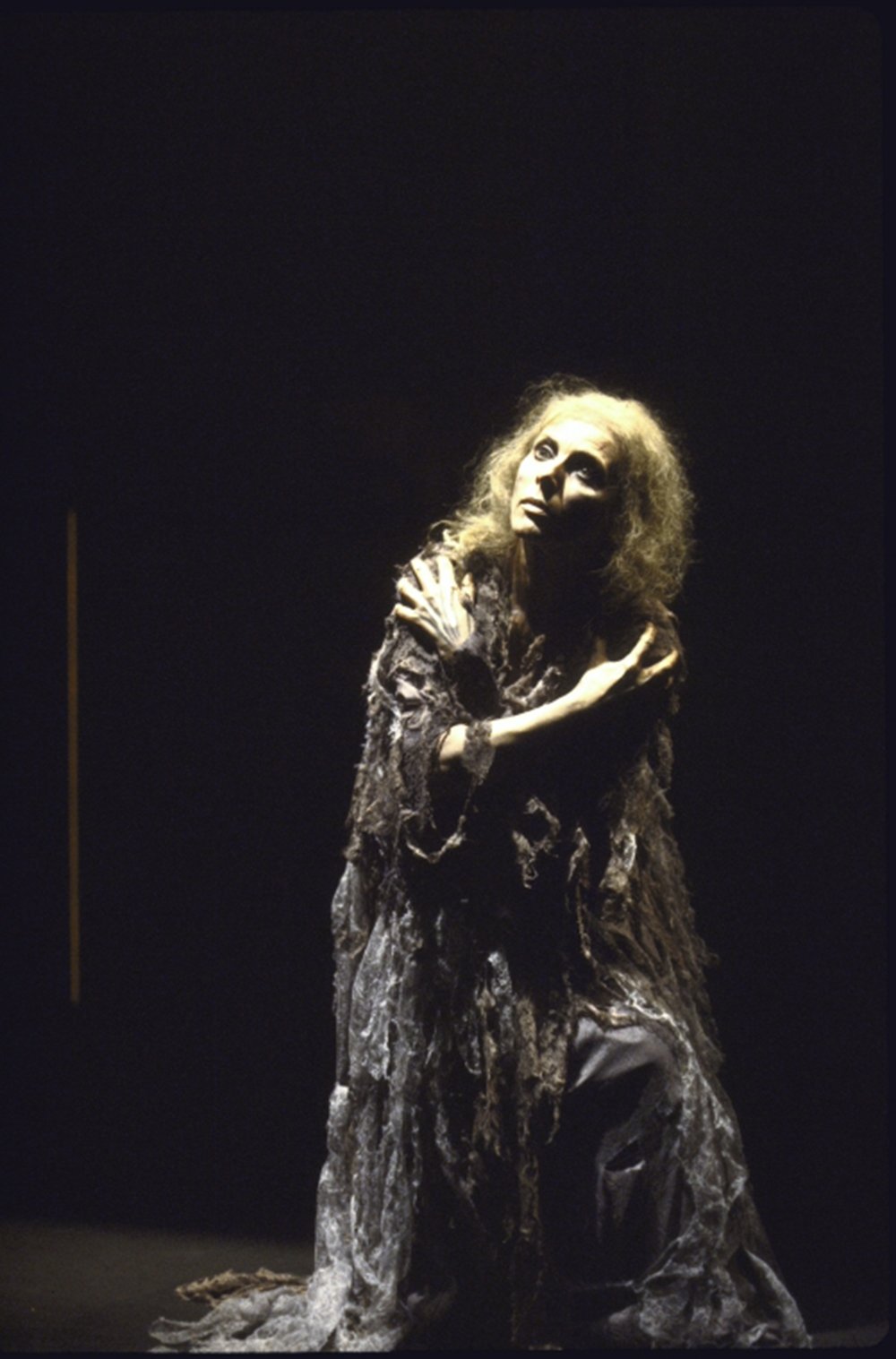

In a late, short play, Footfalls, written many years after her death, he evokes a mother-daughter relationship, in which he gives the speaker the name May, transposed at one point to Amy. It is a tale of unutterable sadness: May is neither bitter nor grotesque, like the mothers in Molloy and End Game, but infinitely sad. She walks and walks, barefoot on the floorboards, and grieves and paces, and paces and grieves. Some commentaries have connected this play with Jung (Beckett went with Bion to hear Jung speak in London during his analysis) and the famous Jungian case of the girl who was never fully born. But I connect it with May Beckett, haunting Cooldrinagh, haunting her bungalow New Place, haunting her son. The play was first performed in 1976, with Beckett’s favorite actress, Billie Whitelaw, as May, and the stage directions describe her “disheveled gray hair, worn gray wrap hiding feet, trailing.” It is a play of aging and endless psychotic repetition. “Slip out at nightfall and into the little church by the north door, always locked at that hour, and walk, up and down, up and down.” May was frozen by “some shudder of the mind,” and Beckett’s pity for her, as for all suffering things, is immeasurable. He took up the theme again, a few years later, in Rockaby (1981), where an old woman (again Whitelaw) with unkempt gray hair rocks herself monotonously as she delivers a monologue with the refrain “time she stopped.” And stop at last she did, as the blind came down. But she never left him.

Adapted from “The Maternal Embrace: Samuel Beckett and His Mother May” by Margaret Drabble, in Writers and Their Mothers, edited by Dale Salwak, published 2018 by Palgrave Macmillan. Copyright © 2018 by Margaret Drabble. Reproduced by permission of SCSC.