The Garden of Earthly Delights (detail), by Hieronymus Bosch, 1490–1510. Prado Museum. These cats appear in the center panel of the triptych and are seen walking in a parade of strange beasts.

Cats feature in many paintings by the old masters, but hardly ever as the principal figure. They are usually tucked away in a corner of a scene, playing a very minor role. One great artist who did enjoy watching cats, however, and sketching their varying moods and postures was Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo is quoted as saying: “The smallest feline is a masterpiece,” and cats appear in at least eleven of his drawings. Sadly, however, they never progress to become a feature of a painting. Perhaps this is not surprising when one considers that, although he produced many hundreds of drawings, he left us only about fifteen finished paintings. This is a staggeringly small output for an artist who gave us some of the world’s greatest masterpieces. The reason for the great rarity of Leonardo’s finished work is that he was one of the world’s great procrastinators. He was always about to start something, but then put it off; or he actually got started but then never finished the work.

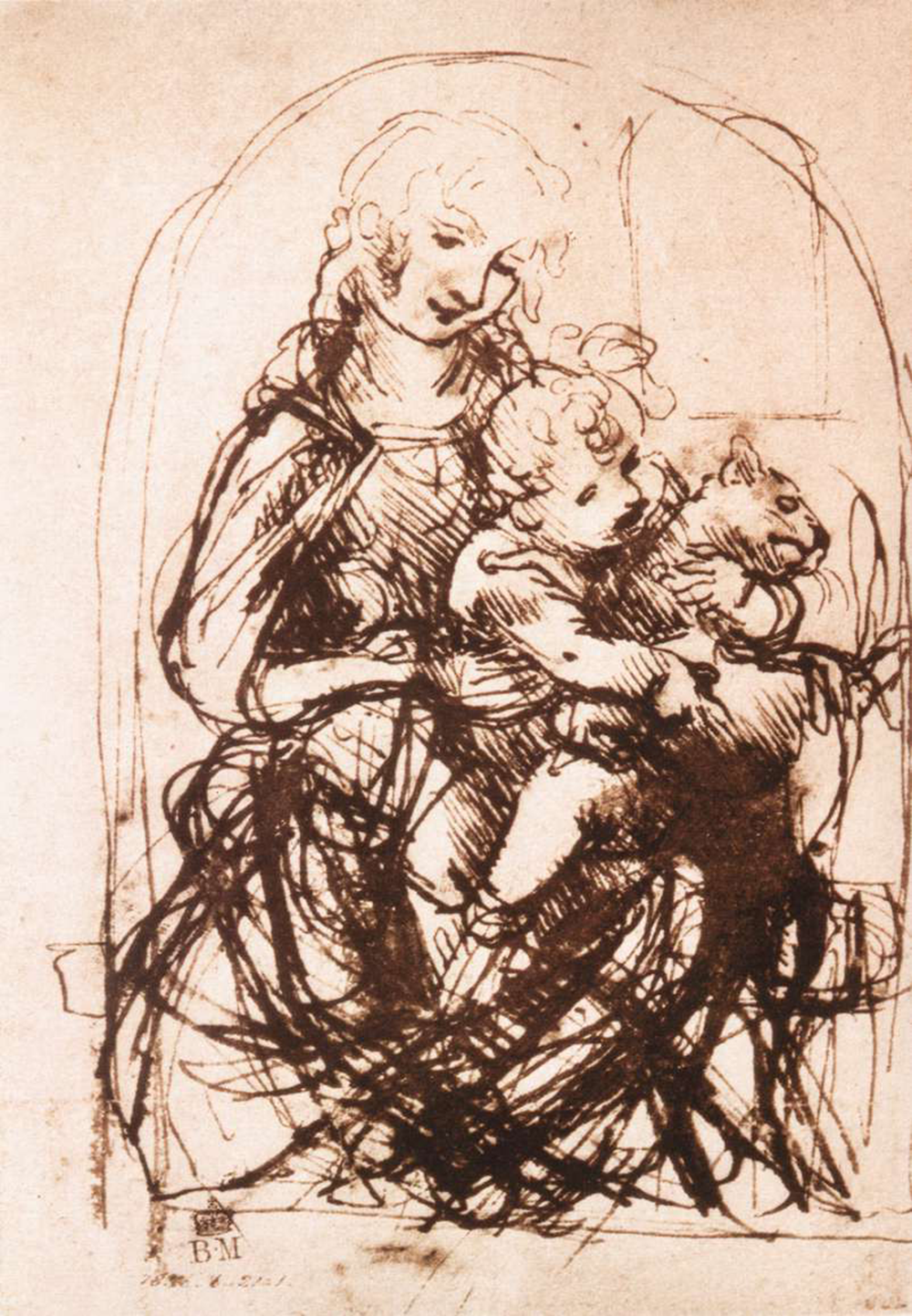

Leonardo’s Madonna with a Cat is a case in point. He was planning to make a painting of the Madonna with an infant Jesus in her arms, and with the child hugging a cat. The subject of the painting was the legend that a cat gave birth at the very moment of the Nativity. He did no fewer than eight preparatory sketches in the 1470s, but the painting itself never materialized or at least has not survived. Apart from his general procrastination, there may have been an additional reason for him not to have completed this particular painting. It is clear from his sketches that he had live models sitting for the painting, including a real woman, a real infant, and a real cat. It is also very clear that this combination was a troublesome one. In each of the sketches, the infant is obviously struggling to keep hold of the cat, and in one of them he appears to be nearly strangling it in his efforts to stop it from jumping down and stalking angrily out of the studio. The animal is drawn by Leonardo with great observational honesty and is shown writhing this way and that, trying desperately to escape.

Anyone who has ever been asked to hold a cat for any length of time to please a photographer will know how difficult this can become once the cat has decided that it has had enough. A dog might stay put for hours, but a cat has a much shorter fuse. Leonardo has brilliantly caught this struggle between infant and cat, but the sketches he made were obviously dashed off at high speed. It must have dawned on him that any attempt to keep the cat there for the many hours needed for a detailed portrait painting would be doomed to failure. As a result, we have been robbed of a finished painting of a cat by the grand master.

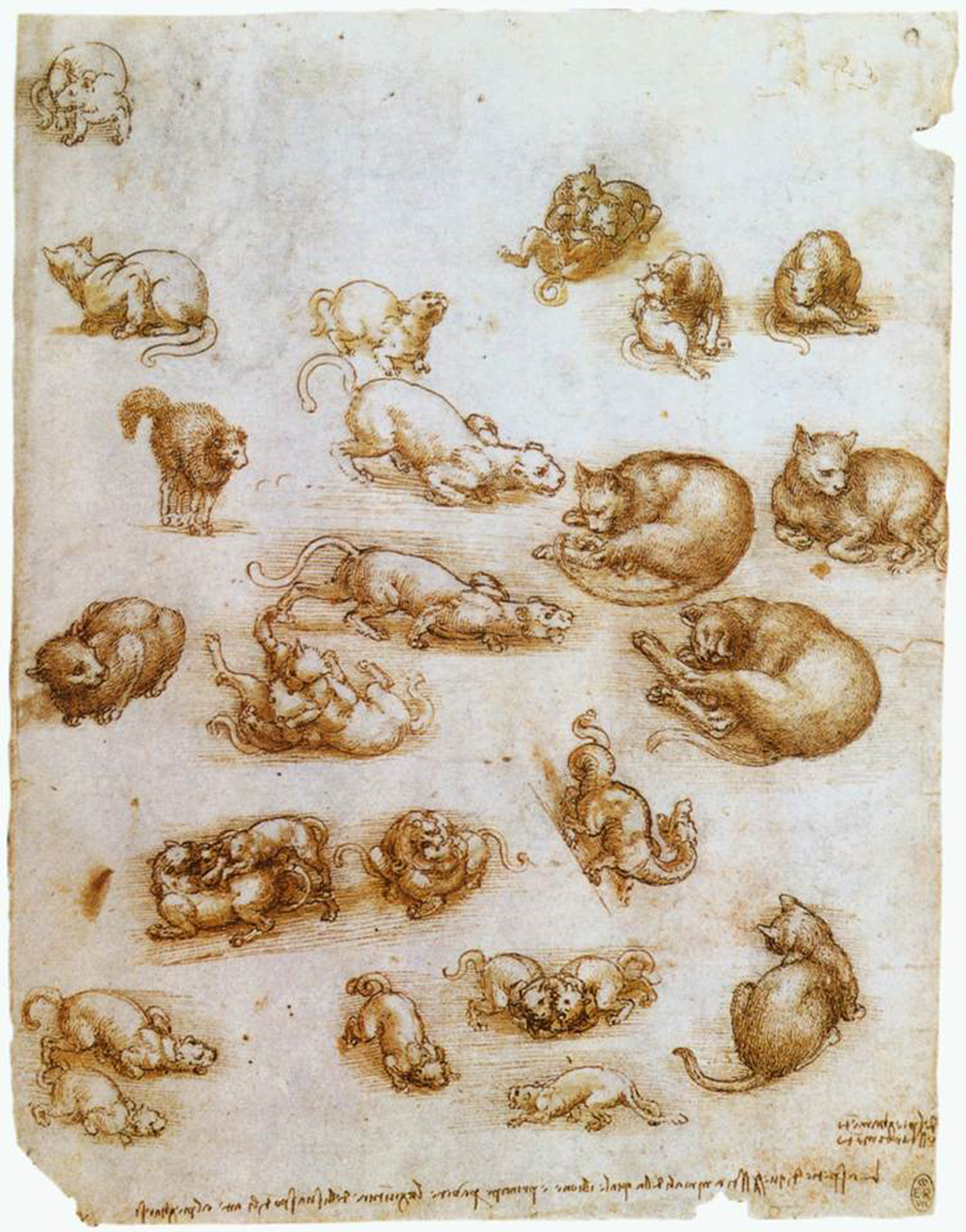

We must be content with Leonardo’s sketches of cats, and although they are only very minor works, some do demonstrate his remarkable powers of observation. These are not pretty, cuddly pet cats; they are almost certainly working house cats kept to control rodents. The artist catches them engaged in typical feline activities: cleaning themselves, rolling over, fighting, resting, crouching, or bristling with fear. An odd feature of his cat images is that although they show highly characteristic feline postures, their faces are unusually pointed—too long for a typical modern pet cat. Whether this was a Leonardo stylization or whether his cats really did have longer snouts, we will never know, but it does somehow reduce their feline appeal, at least to the modern eye.

Leonardo da Vinci was not only a brilliant artist but an extraordinary man, far ahead of his time in many ways. In one of his notebooks he writes: “If you are as you have described yourself, the king of the animals—it would be better for you to call yourself king of the beasts since you are the greatest of them all!—why do you not help them…?” To refer to human beings as animals—even great ones—in this manner in the fifteenth century is truly amazing. When I did so myself as recently as 1967, I was soon under attack, and it is not surprising to read of Leonardo’s caution in the sentence that follows, in which he grumbles: “Even more I might say if to speak the whole truth were permitted me.” In 1519, a few years before his death, he did risk going a little further, when he left himself a memorandum reminding him to “write a separate treatise describing the movements of animals with four feet, among which is man, who likewise in his infancy crawls on all fours.”

With this exceptionally enlightened attitude towards other animal species, it is not surprising that in his time Leonardo was almost alone in taking the trouble to catch so perfectly the moods and movements, postures and actions of the humble house cats of his day. No other old master seems to have enjoyed the direct observation of feline behavior in the way that Leonardo did.

Far to the north of Leonardo’s Italy, working in the Netherlands, was a contemporary of his, Hieronymus Bosch. Both were born in the middle of the fifteenth century, and both died early in the sixteenth. Neither left us many paintings—Leonardo fifteen, Bosch twenty-five—but those they did leave were masterpieces. There was one big difference between them: Leonardo gave us reality, Bosch gave us fantasy. Where cats are concerned, Leonardo’s are caught in moments of natural behavior, while Bosch’s are taking part in arcane ceremonies in some other world.

One of Bosch’s cats is being ridden bareback by a naked man. This makes it as large as a horse, but all sense of natural proportion is lost once you are inside Bosch’s dream world. It is a gray cat with black spots, black feet, a sharply pointed tail, and a long, thin spike sprouting from its forehead. It also has prominent genitals, very large black eyes, and a strange piece of cloth draped over its head. Walking behind it is another cat, also with a naked man on its back. This man is holding a large fish that he is pointing forwards, as if firing a gun; this cat is plain brown in color.

Another of Bosch’s cats, seen walking away from Adam and Eve with a fat lizard held in its jaws, also has a long, tapering, sharply pointed tail. This animal has a brown coat, again covered in black spots, but this time there is a separate patch of white spots on its belly and chest. This form of coloration is unknown among cats and seems to have been invented randomly by the artist to make his cat look strange. The animal also has a pronounced downward arch to its back. In a horse, this hollowed back would be called a swayback or saddleback; the technical term for it is lordosis.

A fourth Bosch cat, in The Temptation of Saint Anthony, is reaching out from underneath a red curtain to grab a large dead fish. Watched by a naked woman, it turns its head towards her and threatens her with an open mouth. Its long, pointed ears curve slightly so that they start to look like horns. This is a devil-cat.

These Boschian cats are not loved, but neither are they hated. They are simply part of a bizarre fauna that swarms all over his major triptychs. Birds, mammals, and reptiles of many different kinds interact with the human figures, and cats are just one of the species illustrated.

Reprinted with permission from Cats in Art by Desmond Morris, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2017 by Desmond Morris. All rights reserved.