Anyone who has spent time in the desert has known a silence so profound that one can almost hear the sun’s rays hitting the ground. Sound was the tomb raider’s enemy; airborne it might easily reach the Medjay, the necropolis police, in their outposts along the mountains, or the priests performing rituals at royal tombs. The tomb doors were visible but sealed so that any disturbance would be obvious. Tunneling into them was tough going; a group of eight men might take a week to clear pits and shafts to penetrate a burial chamber. The utmost stealth was required so the raiders worked after dark. It helped that the necropolis had grown crowded; sometimes they could tunnel from one tomb straight into another. Once they’d gathered the loot, they took it to a secluded place and lit a fire, burning the wooden coffins or statues coated in gold or silver and recovering the pools of molten metal from the cinders once they had hardened in the night-cooled sand. These were scrupulously measured using a stone counterweight and divided among the gang members, as was whatever else the tomb had surrendered.

Whereas the wealth of the early New Kingdom had come from foreign tributes and booty that entered the economy from the top, the tomb-raiding of the late New Kingdom “released a surge of wealth into society from, as it were, the bottom,” reported Barry Kemp in Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization. Theft altered the market, halving the value of precious metals against grain and changing the bartering rates for commodities. In the raid-based economy that coalesced in the reign of Ramses IX, thieves and their accomplices had the most tradable goods, while the go-betweens (traders, shopkeepers, and traveling salesmen) profited from inflated prices placed on items purchased with stolen goods. The black market became a feature of daily life, where booty was bartered for basic needs, like food, clothes, and parties replete with honeyed wine, but also, ironically, for the equipment people desired for their own burials.

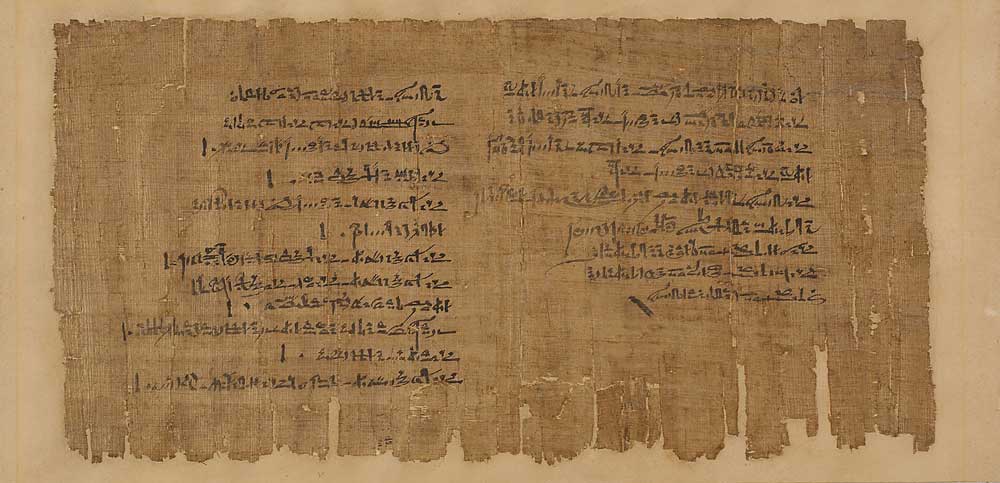

Much of our knowledge of the stolen goods that flooded the market comes from a series of papyrus documents unique in the annals of antiquity, translated, correlated, and interpreted by British Egyptologist T. Eric Peet (1882–1934) in his opus The Great Tomb-Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty (1930). The papyri contain what amount to the court transcripts of investigations into tomb and temple theft that occurred during the reigns of Ramses IX and Ramses XI, including the depositions of witnesses and the accused, the tombs they robbed, the things they stole, the bribes they paid, and evidence of a fencing network extending all the way north to Memphis. We hear the raiders speak, justifying their crimes in startlingly familiar terms: “This inner coffin is ours; it belonged to our great men. We were hungry; we set out…to search for this piece of bread so as to profit from it,” claimed one of the suspects.

The circumstances surrounding the acquisition and analysis of these papyri, mostly purchased in the mid- to late 1800s and later sold or gifted to wealthy collectors or museums, offer an example of the flukes of fate that sometimes accompany archaeological discoveries. Scores of papyri were rescued from the sands enveloping Deir al-Medina by Egyptian raiders who must have wondered what the foreigners planned to do with them. Purchased on a whim, ancient documents languished in sundry collections for decades, awaiting integration into the growing body of Egyptological knowledge. Peet was peeved when he asked if he could get photos of a papyrus in the vast holdings of J.P. Morgan and was told “it might be several years before it was unpacked.” Raiders and their fences scattered artifacts across Egypt, typically without recording their exact provenance so as to avoid detection by the authorities, but Western collectors scattered them around the world, further complicating the matter of their study. Fortunately, the ancients were exacting in their documentation.

A papyrus first translated by Czech Egyptologist Jaroslav Černý (1898–1970) and reexamined by Peet, the so-called Papyrus Ambras, is dated year six of Ramses XI (c. 1088 bc). It relates how two clay vessels full of documents that were probably stolen from the archive of Ramses III’s temple during the unrest that occurred there twenty years earlier had been “found by people of the land” and returned to the temple, where they were duly inventoried. One of the jars contained documents “concerning the thieves” and the trials that took place during the reign of Ramses IX, that is, some of the very same papyri that Peet was examining more than two thousand years later. As much as it must have thrilled him to identify the documents at hand as the former occupants of that ancient clay jar, Peet was vexed by lacunae and the fragmentary nature of some of the papyri. A year after his death, in 1935, the missing upper half of one of the documents he examined (Amherst Papyrus) cropped up among the souvenirs King Leopold II of Belgium had acquired in Egypt, stuffed inside a statuette by a local broker to sweeten the deal. In a strange case of historical symmetry, the Amherst Papyrus, in which Twentieth Dynasty thieves confessed their crimes, had apparently been torn in two by nineteenth-century raiders to divvy up their shares.

The earliest trials recorded in the papyri Peet studied were held in year sixteen of Ramses IX’s reign (c. 1107 bc), when the army was busy with the Libyans, grain was scarce, and gangs of raiders from every walk of life were having a field day. The court process involved the vizier and a group of high officials who acted as prosecutor, judge, and jury, in addition to scribes who recorded the proceedings. Suspects were rounded up, often with their wives, and questioned one by one. All were required to swear an oath to tell the truth on pain of mutilation or of being “placed on the stake” or banished to a faraway place to work in mines or quarries. Interrogations involved torture regardless of gender, including the bastinado (foot whipping). A stout stick was used for more general beatings. Suspects were also placed in wooden hand- or ankle-cuffs that were tightened or twisted, shedding fresh light on the etymology of the expression “he twisted my arm.” The cases of those deemed guilty were referred to the pharaoh for sentencing. Egyptians did not take bloodshed lightly; impalement was reserved for the greatest of crimes, among which tomb-raiding ranked highly.

For the sake of concision, scribes pared the proceedings down to laconic, oft-repeated phrases such as “He/she was examined with the stick” and said, “Stop, I will tell you!” or, in the case of those proclaiming innocence, “Far be it from me [to have stolen anything]!” Sometimes conflicting witnesses were made to confront one another, and one of them backed down. Some witnesses implicated others in the crimes of which they were accused, like the woman who was questioned about the silver her husband had swiped and said she never saw any silver in her house, and that the court should try asking his mistress. Members of the raiding gangs were often related, people who knew and might trust one another. Some were experts, with knowledge of tomb construction and locations. We can imagine them comparing notes about the habits of the police, identifying those easily fooled or bribed, discussing how heavy objects were best handled, relating past mishaps or tales of eleventh-hour escapes from detection or disaster. But whatever code of honor or friendship the thieves may have shared was forgotten when their lives were literally at stake. In the course of interrogations, whether in hope of a lighter sentence or simply to stop the beatings, raiders readily submitted the names of their partners and anyone else implicated in the crime.

As for the trials’ aim, the delivery of justice was incidental; the main objective was the recovery of stolen goods that were confiscated by the state. The trials also served as proxy battles between high officials, who used them to legitimize themselves as upholders of the law while settling scores through blame-laying, a tactic still popular among politicians. Such was the case in year sixteen of Ramses IX, when Paser, the mayor of east bank Thebes, claimed there had been thefts in the Great Place, which was under the jurisdiction of his west bank counterpart and rival, Pawero, chief of the necropolis police. Pawero immediately went on the offensive, also denouncing the thefts to the vizier, who personally inspected the ten tombs of “the blessed ones of days gone by” that Paser had mentioned, accompanied by the royal butler. Three had been violated, including the resting place of Sobekamsef, a Seventeenth Dynasty pharaoh, and those of two lesser personages. One of the perpetrators described opening the outer and inner coffins of Sobekamsef’s four-hundred-year-old tomb and finding the pharaoh

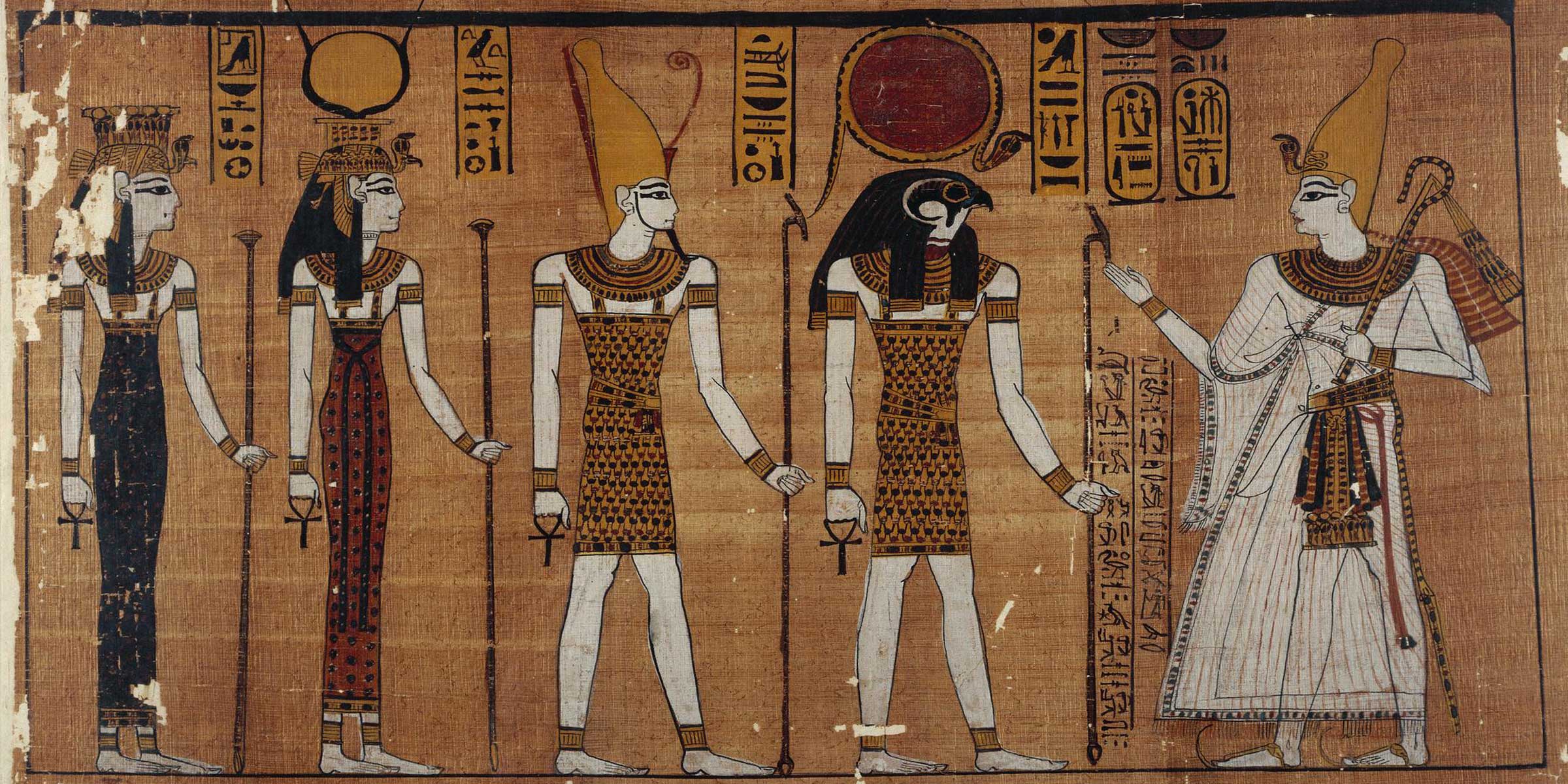

equipped like a warrior. A large number of sacred-eye amulets and gold was at his neck, and his headpiece of gold was on him. The noble mummy of this king was all covered with gold and his inner coffins were bedizened with gold and silver inside and outside with inlays of all kinds of precious stones. We appropriated the gold we found on this noble mummy of this god…We set fire to [the] inner coffins. We stole their outfit…consisting of objects of gold, silver and bronze and divided them up among ourselves.

The take from this tomb was 160 debens of pure gold, 14.5 kilograms (32 pounds), the largest amount on record but a small indication of the quantities of finely wrought treasures that were unearthed over time and melted down for barter.

Among the suspects Pawero had rounded up were two carpenters and three masons, tomb builders gone bad, in addition to a farmer and a water carrier. All were expeditiously questioned and beaten, and duly confessed. “Their trial and their doom was set down in writing and a dispatch was sent to Pharaoh.” That same night, probably on Pawero’s prompting, necropolis staff crossed the river to celebrate what they considered their vindication, since most of the tombs were found intact. Paser took exception to their taunting, saying, “You have rejoiced over me at the very door of my house. What do you mean by it?” He reminded them that the robberies that were discovered were no small crime, and threatened to take the matter directly to the pharaoh. But Pawero’s maneuvering with the vizier and his direct authority over the necropolis workers left Paser humiliated and obliged to back down. The investigations meanwhile called attention to the sorry state of the necropolis, and rather than exonerating the officials responsible for its safekeeping, only heightened suspicions that they were aiding and abetting theft.

Reprinted with permission from A Short History of Tomb-Raiding: The Epic Hunt for Egypt’s Treasures by Maria Golia, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2022 by Maria Golia. All rights reserved.