Interior of Riverside Church, 2012. Photograph by Ad Meskens. Wikimedia Commons.

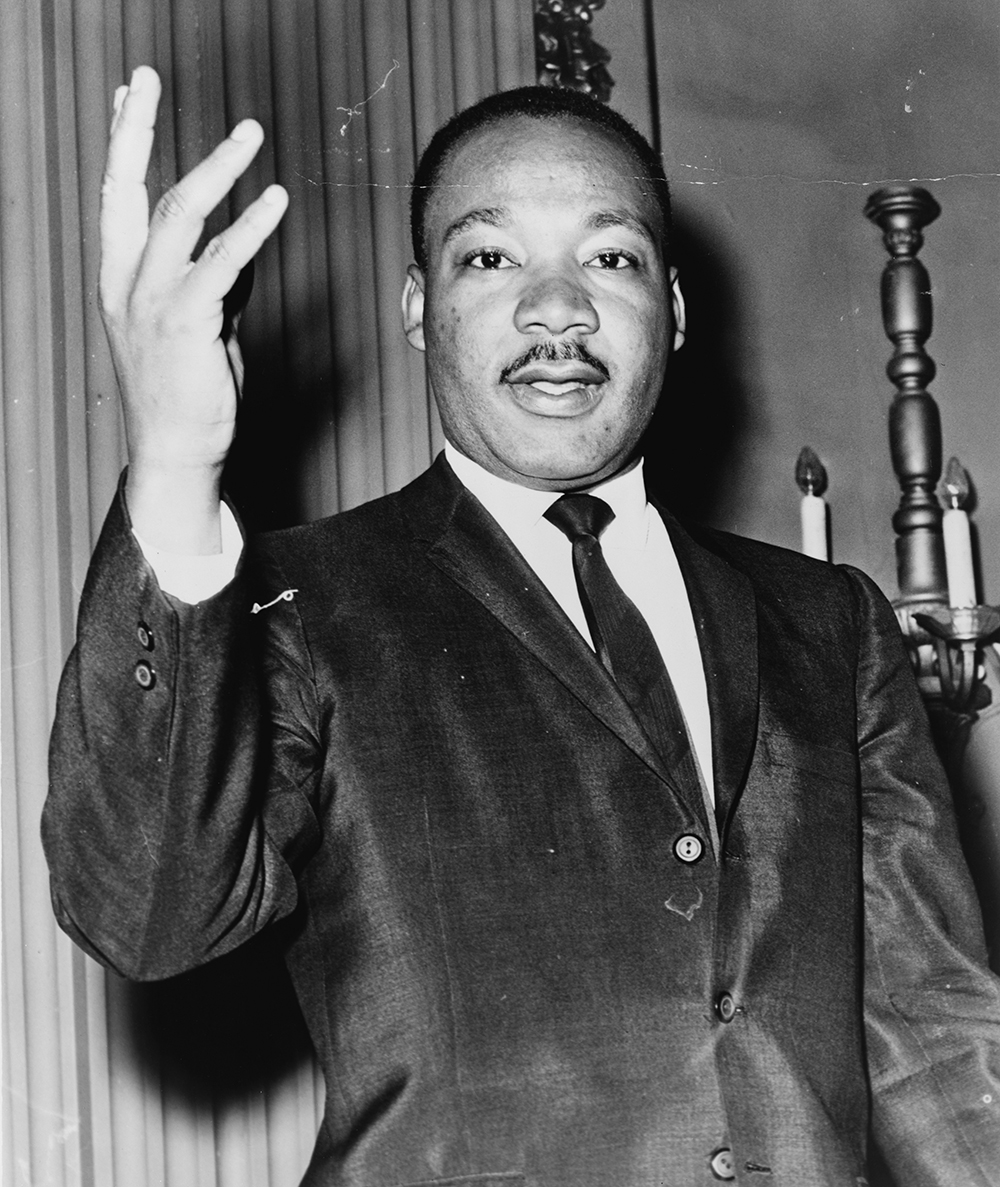

On April 4, 1967, a crowd of almost four thousand gathered to hear Martin Luther King Jr. speak from the pulpit of New York City’s Riverside Church. King denounced the Vietnam War in unequivocal terms. “I come to this platform to make a passionate plea to my beloved nation,” he explained early in the speech. King’s criticism of military escalation in Vietnam and the declining effectiveness of the war on poverty had severed his political alliance with President Lyndon Johnson. The Great Society’s political shortcomings were now an unfolding moral disaster—“the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.” Racial apartheid’s grip on American democracy, argued King, corrupted the nation in war and peace, hurling large numbers of poor black and white soldiers toward a death march in international slaughter fields. King challenged America’s moral and political authority to wage war in Vietnam by comparing the military’s use of force overseas to the black youth throwing Molotov cocktails to wage rebellion in urban ghettos. Both used violence in service of larger ambitions that, King suggested, represented political and moral dead ends.

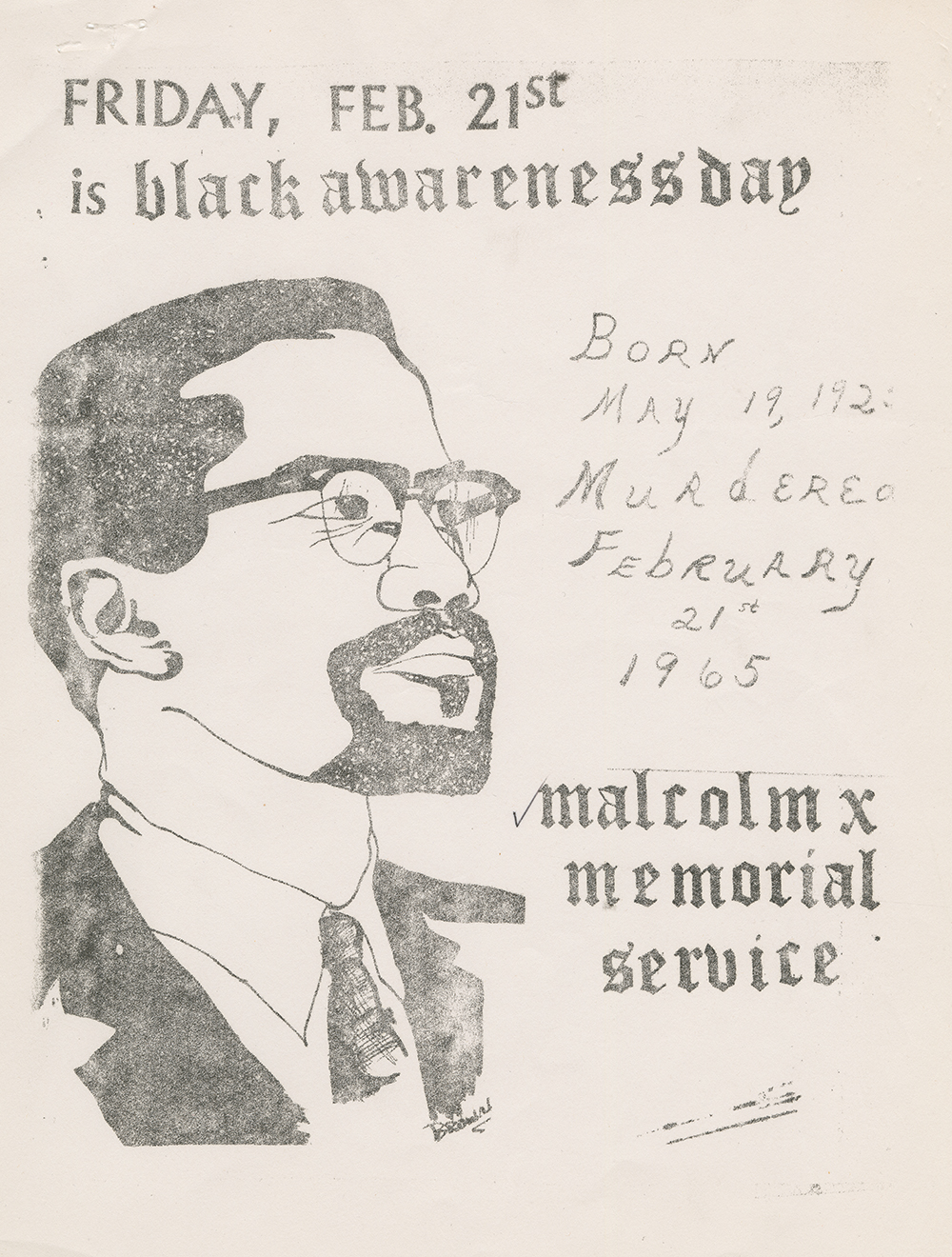

Riverside marked King’s transition from a civil rights leader into a political revolutionary, one who refused to remain quiet in the face of domestic and international crises. The speech represented the boldest political decision of his career. Despite King’s proclaimed belief in the roots of American democracy, he publicly assailed the hypocrisy behind the country’s posture as liberty’s surest guardian around the world. In the months before his death, Malcolm X, too, had discussed the Vietnam War, marveling at how courageous peasants, “with nothing but sneakers on and a rifle,” were defying the world’s greatest military power. But even as King decried America as pursuing a catastrophic trajectory rooted in greed, violence, and racism, he found optimism in the potential for democratic transformation. At Riverside, King assumed Malcolm’s previous role as black America’s prosecuting attorney, publicly denouncing the war in Vietnam by offering a political seminar on American imperialism, racism, and economic injustice that announced his formal break with mainstream politics.

In a preemptive strike against critics who would accuse him of confusing his civil rights leadership with foreign policy expertise, King cited Langston Hughes, “the black bard of Harlem,” explaining that “America never was America to me.” “If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned,” reasoned King, “part of the autopsy must read Vietnam.” King was squarely confronting American political hubris by characterizing the Vietnam War as the nation’s Achilles’ heel. He considered foreign policy analysis to be a substantive part of his role as a civil rights leader. Domestic and international struggles for justice and equality were never mutually exclusive but, on the contrary, intimately connected in a manner that demanded forthright criticism. For King, America remained, at its best, a country filled with unrealized potential—as Hughes’ poetry brilliantly evoked—but whose promise receded the further the nation strayed from its core values of liberty, freedom, and democracy. King characterized American soldiers in Vietnam as “the victims of our nation” and “strange liberators” who ravaged peaceful villages, killed innocents, and impoverished peasants. His anti-war criticism echoed and amplified Malcolm X’s denunciations before his death, when he characterized Vietnam as “the struggle of the whole Third World” against Western imperialism.

Like Malcolm X, King publicly wrestled with the grandeur and travails of American democracy. King confronted Johnson’s intransigence on the war with a biting quote from his predecessor, the late John F. Kennedy: “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.” Kennedy had spoken these words almost five years earlier, during the wave of demonstrations, arrests, and violent reprisals that forced a sitting U.S. president to confront the nation’s racial demons for the first time in a century. The stakes, now global in scope, had only escalated since Kennedy’s time, introducing a precarious new era where the world seemed perpetually poised on a knife’s edge of destruction.

King’s all-encompassing solution relied on what he called a “revolution of values” led by Americans uneasy about growing economic inequality, ashamed of a bloody history of racial oppression, and embarrassed by a rush to war that tarnished a hard-earned postwar reputation as the guardian of the free world. “War is not the answer,” King pleaded, although the entire world appeared on the brink of “revolutionary times.” King contextualized Marxism’s global appeal in America’s failure to embrace its democratic potential.

Confronting “the fierce urgency of now” required new levels of moral and political courage, not only to defy the “cruel manipulation of the poor,” but to illuminate how racial segregation, urban poverty, and burning embers in Detroit and Hanoi were inextricably linked. King displayed a rueful awareness of institutional racism’s contemporary power by naming “my own government” as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” Like Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and Black Power activists, King now defined violence expansively, finding a common denominator in the manner in which poverty, segregation, racism, and domestic and international violence converged in a discordant, jangling symphony of oppression.

And yet the “beautiful struggle” King outlined set him on a lonely political journey. After Riverside, one poll found that 73 percent of Americans disapproved of his Vietnam stance. Sixty percent judged his peace efforts as hurting the movement. Members of the House Armed Services Committee counted themselves among King’s most powerful detractors. Congressmen L. Mendel Rivers of South Carolina and F. Edward Hébert of Louisiana led the charge in an effort to convince the Justice Department to punish King, for supporting conscientious objectors against the draft, and Carmichael, for turning “Hell no, we won’t go!” into a national anti-war chant. Higher-education leaders followed suit, with the dean of the Notre Dame Law School attacking King and Carmichael as “either Communists or traitors” who had betrayed the nation by opposing the war in Vietnam.

King’s call for peace included publicly advocating a universal cease-fire, a cessation of bombing, recognition of the National Liberation Front by the American government, and the removal of all foreign troops in Vietnam. Not even King’s statesmanship could hide the fact that his speech at Riverside had brushed aside his long-standing strategic embrace of political reform. He now openly supported a human rights revolution that would turn America into a beacon of social justice and racial equality on a scale unimagined by the architects of the Great Society. But if Malcolm X had remained, until his death, eternally skeptical of American democracy’s capacity to guarantee racial and economic justice, King maintained defiant faith in the capacity of massive civil disobedience to bend the will of presidents and political leaders. This faith inspired King to create new coalitions with the peace movement, New Left radicals, and Black Power activists, all of whom found common ground in rejecting the Vietnam War as an example of American hubris, racism, and injustice. While critics labeled him politically reckless, King plotted a radical course, buoyed by his unyielding belief in the power of ordinary citizens to effect lasting social change.

Large segments of America interpreted King’s cry for peace as an act of war. Standing ovations received inside the friendly confines of Riverside were overwhelmed by the contempt of journalists, pundits, and politicians who viciously questioned his political judgment. The Johnson administration opted to ignore King, afraid that his anti-war remarks might spread across the spectrum of civil rights leadership. Ralph Bunche, the first African American winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, who had verbally sparred with Malcolm X, now denounced King. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who almost a year earlier had forwarded the White House a report on potential racial unrest that cited forty-five cities on the verge of rebellion, now furnished Lyndon Johnson with the text of King’s Riverside speech, which threatened to damage the president far more than any race riots could. The FBI also furnished copies of its updated negative Martin Luther King Jr. dossier to the attorney general, Secret Service, secretary of state, and secretary of defense. The document argued that King’s latest speech revealed him to be a tool of American communists.

King’s speech made front-page headlines, competing with the White House’s announcement of plans to send doctors to Vietnam to investigate allegations of napalm being used indiscriminately against civilians by the American military, an effort to cauterize the festering national wound of Vietnam. After Riverside, King became America’s most well-known anti-war activist, lending a Nobel Prize winner’s moral currency to a peace movement struggling to find its voice in a political landscape where most Americans still supported the war. Riverside transformed King, who became emboldened by the diverse throngs of supporters—religious leaders, young people, and the elderly, black and white, who gave him a standing ovation at the end of his hour-long speech—while facing soured political alliances and condemning press coverage. Media outlets that once lavished praise on King after his Nobel and civil rights victories in Birmingham and Selma now harshly criticized his strategic judgment and political temperament. Urban League leader Whitney Young publicly advocated keeping issues of war and racial justice separate, perfectly aligning with the White House’s efforts to inoculate the larger civil rights struggle against King’s anti-war talk. Edward Brooke, the first black man elected to the U.S. Senate in a general election, characterized King’s Vietnam position as “very costly,” because it sullied not only his reputation but the entire movement. Barry Goldwater accused King of inflicting “irreparable harm” on the civil rights movement. The group Jewish War Veterans characterized King’s Riverside address as an “insult to the intelligence of all Americans,” while his friend and longtime supporter Jackie Robinson offered the most diplomatic criticism: “Dr. King has always been my favorite civil rights leader, but I don’t agree with him on this issue.”

The New York Times termed the speech “Dr. King’s Error,” citing it as a tragic misstep for civil rights and peace advocates that might prove “disastrous for both causes.” The paper criticized King’s entrée into anti-war activism as a distraction that sapped vital energies from racial hotspots in Chicago, Watts, and Harlem. Suggesting that the “moral issues” of war were far from “clear-cut,” the paper attacked King for linking Vietnam and racial justice and blasted him for sowing “deeper confusion” in a country beset by growing polarization.

Excerpted from The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. by Peniel E. Joseph. Copyright © 2020 by Peniel E. Joseph. Available from Basic Books.