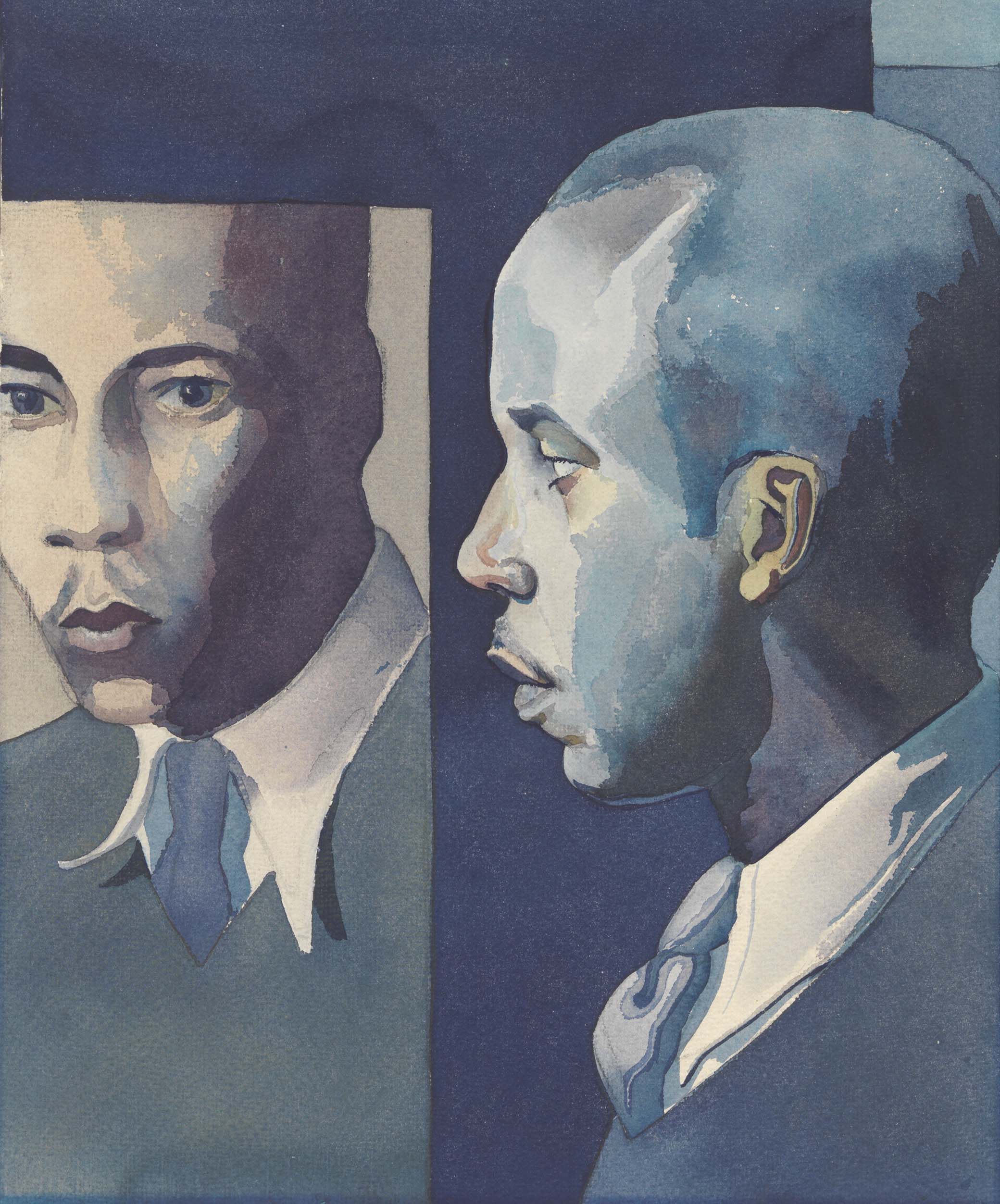

Self-Portrait, by Samuel Joseph Brown Jr., c. 1941. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Pennsylvania WPA, 1943.

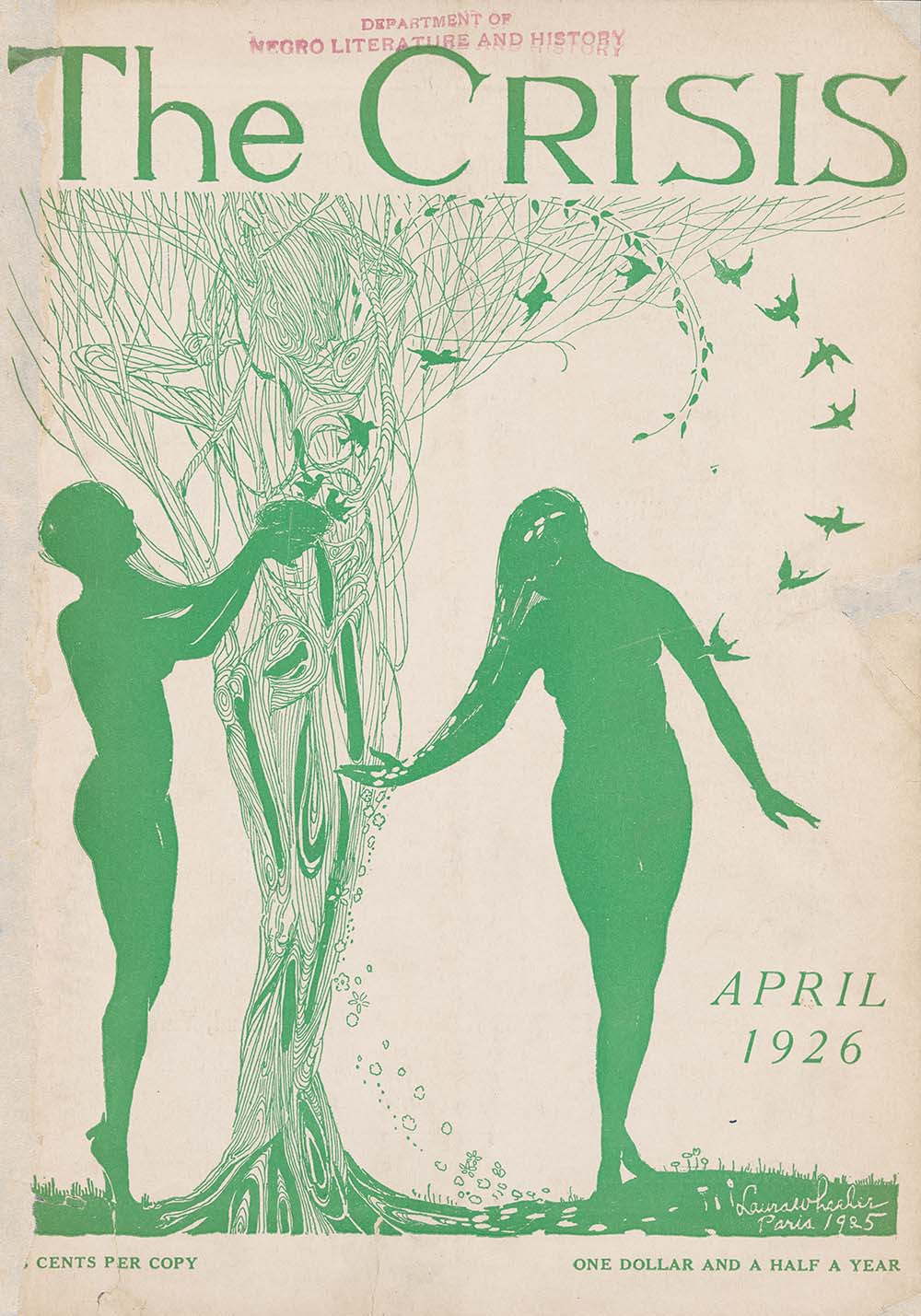

Debates about the representation of African Americans circulated throughout the 1920s—what kinds of depictions should be encouraged, who should be responsible for them, and what role black artists had in responding to negative descriptions and uplifting the race. These themes served as the subject of W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1926 symposium, “The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed?” hosted in the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis. Even a cursory glance at the responses to Du Bois’ question reveals that few believed African Americans were duty bound to direct their art to the cause of social justice. The unencumbered freedom of the artist, many argued, was far too important. As playwright and novelist Heyward DuBose argues, who himself was not an African American, black people must be “treated artistically. It destroys itself as soon as it is made a vehicle for propaganda. If it carries a moral or a lesson, they should be subordinated to the artistic aim.”

Du Bois’ essay “Criteria of Negro Art” is his answer to the symposium that he organized. But whereas most read this essay as the dividing line (and there is some truth in this) between Du Bois and many in the Harlem Renaissance, especially the writer and philosopher Alain Locke, the essay suggests closer proximity between these two figures. They each were seeking to avoid black artists needing to manage the unacceptable demands of what Langston Hughes called the “undertow of sharp criticism and misunderstanding” from black people and “unintentional bribes from whites.” The choice must not be between the demand, “Oh, be respectable, write about nice people, show how good we are,” and the equally unacceptable request, “Be stereotyped, don’t go too far, don’t shatter our [white people’s] illusions about you, don’t amuse us too seriously. We will pay you.”

Du Bois delivered “Criteria of Negro Art” at the NAACP’s annual meeting in Chicago in 1926. He subsequently published the lecture as part of “The Negro in Art” multi-issue series that appeared in The Crisis. In “Criteria,” an essay that seeks to embolden black artists against the humiliating and exclusionary standards imposed on them by white America, Du Bois offers one of his most oft-repeated statements: “Thus all art is propaganda and ever must be…I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy.”

In isolation, the first of these sentences might well strike the reader as strange, especially for those of us who see in propaganda the opportunity to manipulate and deceive the public. In the 1920s there was a great deal of misunderstanding about Du Bois’ use of the term. The passage is prefaced, however, by Du Bois’ explicit explanation that artists are conveyers of moral and political truth, in possession of tools for bringing truth into view for their fellows:

First of all, he has used the truth—not for the sake of truth…but…as the one great vehicle of universal understanding. Again artists have used goodness—goodness in all its aspects of justice, honor, and right—not for [the] sake of an ethical sanction but as the one true method of gaining sympathy and human interest.

When Du Bois weds truth and goodness to the artist’s work and art to propaganda, he means for the reader to understand art as a vehicle for expanding the horizon of the recipient.

This seems an odd use of propaganda. This is because we typically associate propaganda with manipulation or partial facts masked as truth. This was a prominent view during the interwar period. For example, both the journalist Walter Lippmann and Edward Bernays (the father of public relations) served on the Committee for Public Information, an arm of the federal government tasked with influencing public opinion during World War I. In their works of the 1920s, both underscored the public’s susceptibility to propaganda, although Bernays clearly believed he could redeem propaganda in the name of democratic governance.

Du Bois is sensitive to this view. But he aims to return his audience to an older use of propaganda—a view in which propaganda meant propagation of faith believed to be true. For Du Bois’ part, it is the propagation of a fuller depiction of African Americans that cuts against partial or one-sided portrayals. This is why Du Bois encourages black artists to resist the need to satisfy their white audiences’ desire for “literary and pictorial racial prejudgment[s] that deliberately distort truth and justice, as far as colored races are concerned.”

Two questions nonetheless present themselves. How should we understand Du Bois’ use of the language of truth and goodness? And how do these two terms help illuminate the interior meaning of the work of black artists?

Du Bois’ interest in propaganda emerges in two other places (although not only two) worth considering. The first is his earlier 1921 editorial in The Crisis, “Negro Art.” The second, almost a decade after “Criteria,” is in his 1935 book Black Reconstruction. It is worth saying a word about both of these reflections.

In the first—“Negro Art”—Du Bois rejects a one-sided view that African Americans often present of themselves. This turns out to be, on Du Bois’ account, the negative description of propaganda.

Negro art is today plowing a difficult row chiefly because we shrink at the portrayal of the truth about ourselves. We are so used to seeing the truth distorted…that whenever we are portrayed on canvas, in story, or on the stage as simply human with human frailties, we rebel. We want everything that is said about us to tell of the best and highest and noblest in us. We insist that our Art and Propaganda be one.

This is wrong, and in the end it is harmful. We have a right, in our effort to get just treatment, to insist that we produce something of the best in human character and that it is unfair to judge us by our criminals and prostitutes. This is justifiable propaganda.

On the other hand, we face the Truth of Art. We have criminals and prostitutes, ignorant and debased elements just as all folk have. When the artist paints he has a right to paint us whole and not ignore everything which is not as perfect as we would wish it to be.

Du Bois intends to direct his comments to an African American audience. He rejects those who insist that we ought only to tell of the best and noble in black life. This is harmful, Du Bois believes, because it will undercut expressive autonomy. But notice that he ties justifiable propaganda to a fuller depiction of black life. Just as we should not insist on only painting positive images of black people, we should not exaggerate the more unsavory elements that form part of them and their community. By 1926, Du Bois does not betray his earlier claim that we should not insist on art and propaganda being one. Rather, that unity must be justifiable—that is, it must not be partial in its substance or aims.

Du Bois comes back to this distinction between positive and negative propaganda in Black Reconstruction. This work intends to correct the view that Reconstruction represented the most backward period of the country in large part due to the perceived moral and political elevation of black people over their white counterparts in the South. In his chapter “The Propaganda of History,” Du Bois reflects on the uses and abuses to which historians have put history in their telling of Reconstruction:

If, on the other hand, we are going to use history for our pleasure and amusement, for inflating our national ego and giving us a false but pleasurable sense of accomplishment, then we must give up the idea of history as a science or as an art of using the results of science and admit frankly that we are using a version of historic fact in order to influence and educate the new generation along the way we wish.

Du Bois’ phrase “the way we wish” suggests something contrary to what the facts permit and truth demands. He is essentially tracking the use of “truth” he invokes in “Criteria.” In both works, he is concerned with beliefs that come wholly unhinged from the past and present and therefore function as unassailable claims:

It is propaganda like this that has led men in the past to insist that history is “lies agreed upon”; and to point out the danger in such misinformation. It is indeed extremely doubtful if any permanent benefit comes to the world through such action. Nations reel and stagger on their way; they make hideous mistakes; they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things. And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all this, so far as truth is ascertainable.

The partiality of the historians of Reconstruction distorts the truth and for just this reason fails to illuminate human life and provide guidance.

Lest we read too much into this, Du Bois is not concerned with reporting what philosopher Leonard Harris calls an “objectively real truth” in history. He is clear that we should tell the truth so far as it is ascertainable, acknowledging in that formulation that truth may elude our grasp. Du Bois is more interested in one’s motivation toward the practice of narrating history. We might say Du Bois confronts us with a question: Is one concerned with participating in a practice of giving and asking for reasons for the beliefs one holds about the past as one engages in historical narration? Is one tethered, as the scholar Paul Taylor says, “to the commitment to getting things right,” and thus disciplined by the various epistemic practices involved in trying to get things right? Du Bois’ claim is that Reconstruction historians have not been interested in participating in this practice any more than the artists who have told partial stories and offered one-sided depictions of black people. In this way, Du Bois joins Anna Julia Cooper’s 1892 longing in A Voice from the South for “an authentic portrait, at once aesthetic and true to life, presenting the black man as a free American citizen, not the humble slave of Uncle Tom’s Cabin—but the man, divinely struggling and aspiring yet tragically warped and distorted by the adverse winds of circumstance, has not yet been painted.” To say it is propaganda “like this” that distorts implies there is some other way to conduct propaganda. This other way is found in its most explicit form in “Criteria.”

Du Bois’ description in “Criteria” of art as a vehicle for persuasion provides a perspective with which to understand his broader approach. In “Criteria,” but also “Negro Art” and Black Reconstruction, he is not merely providing direction to would-be artists; rather, he means to signal something about his method as a writer. He treats art as a broader category that is engaged in persuasion. It includes his literary engagements with the public, and not merely those expressed by his fiction and theatrical productions such as The Quest of the Silver Fleece (1911), The Star of Ethiopia (1913), or Dark Princess (1928). One notices this at the very outset of The Souls of Black Folk (1903): “Study my words with me…seeking the grain of truth hidden there.” Souls is thus the product of an artist of letters; it exemplifies the aims stipulated decades later in “Criteria.” In it Du Bois seeks to expand the horizon of the recipient—to cultivate a sympathetic imagination. As an artist of letters, what we should call a rhetorician, Du Bois employs propaganda to provide access for African Americans to “love and enjoy,” and this consciously informs his work. Or to put it differently, Souls is an attempt to persuade his white counterparts to embrace an alternative view of America in which African Americans can experience love and joy unhampered by domination.

Excerpted from The Darkened Light of Faith: Race, Democracy, and Freedom in African American Political Thought by Melvin L. Rogers. Copyright © 2023 by Melvin L. Rogers. Reprinted by permission.