Seven Day Diary (Not Knowing), Day One, by John Cage, 1978. Smithsonian American Art Museum, bequest of Moses Lasky, 2004.

In June 1940, as the Nazis marched into Paris, the French interior and furniture designer Jean-Michel Frank procured a visa in Bordeaux and sailed to Lisbon with his boyfriend. Within days France had surrendered to the Germans, the prelude to some 76,000 French Jews being rounded up and sent to death camps. It was, you might say, a fate that Frank narrowly escaped—except by then he was already dead by his own hand. In March 1941, physically ill and mentally frail, narcotics no longer providing adequate solace and the world burning around him, he decided he’d had enough. “I ask all my friends who have been so good to me to forgive me,” he wrote in his suicide note before taking a fatal overdose of barbiturates in a New York apartment.

Ten days earlier, Frank had turned forty-six. Startling extremes defined his brief life: wealth and privilege, tragedy and loss, artistic discipline and dedication, debauchery and anarchy, marginalization and glory. His celebrated decor aesthetic, a finely distilled compound of extravagance and austere simplicity, grandeur minus fuss and froufrou, had been a bulwark against the darkness and chaos that ultimately proved overwhelming. “No doubt he jumped out of this era because he found it uninhabitable,” Jean Cocteau wrote in 1945. “His death was the prologue of the drama, the red curtain falling between a world of light and a world of night.”

Museumgoers can stumble upon examples of Frank’s furniture in the collections at Cooper Hewitt, the Museum of Modern Art, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. The Metropolitan Museum of Art lacks anything by the designer only because former longtime curator Jared Goss, to his regret, was unable to find a piece that he felt exemplified Frank’s obsession with simplicity and perfection. Many companies sell Frank reproductions; Hermès has a line of official reissues. Yet while Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Florence Knoll, and Arne Jacobsen have become bywords for mid-century modern style, the name Jean-Michel Frank has never quite entered popular awareness, despite his enduring imprint on our visual culture. Contemporary versions of the Parsons table, conceived by Frank in the 1930s when he lectured at the New York art school’s Paris branch, are so ubiquitous as to be practically invisible. His “Confortable” cubic armchairs and sofas have likewise spawned countless imitations, their provenance obscured by time and repetition. Among interior designers of the current era, many of whom regularly source original Frank pieces and find inspiration in photos of his interwar decorative schemes, he is a foremost influence.

Frank’s status as a designer’s designer dates back to the 1920s and ’30s, when he was admired by his peers in an occupation that was in its infancy internationally. The first professional interior designer in the U.S., a former actress from New York named Elsie de Wolfe, launched her career in 1905. Her bright, cheerful, anti-Victorian arrangements, accented by leopard print, chinoiserie, and green-and-white chintz, attracted tastemakers and bluebloods like the Fricks and the Vanderbilts. The cachet of airy, uncluttered spaces was a reaction against the crammed and caparisoned homes of the nineteenth century, when bareness denoted poverty of taste and resources. De Wolfe both foresaw and, in popularizing the new minimalism, hastened the pendulum’s swing the other way. Her 1913 book, The House in Good Taste, was a best seller. “We attribute vulgar qualities to those who are content to live in ugly surroundings,” she cautioned in it. “We endow with refinement and charm the person who welcomes us in a delightful room.” A fan of Frank’s furniture designs, with their understated silhouettes and neutral colors, de Wolfe used them in her own Paris apartment and in her clients’ homes.

De Wolfe had a British counterpart and competitor—Syrie Maugham, “The Princess of Pale”—who made a name for herself in the 1920s with her achromatic schemes. She favored “pickling” wood furniture regardless of its antique pedigree, creating a whitewashed effect. “One day darling Syrie will arrange to be pickled in her own coffin,” de Wolfe sniped. Maugham’s first store opened in London in 1922, followed by branches in California and New York. She bought Frank’s furniture and accessories for her well-heeled clients, who were required to surrender all creative and financial decisions to their imperious decorator. “If you don’t have ten thousand dollars to spend, I don’t want to waste my time,” Maugham informed one apparent penny-pincher. In 1933 her own London drawing room caused a sensation when it appeared in The Studio, a leading art magazine. The all-white room featured several pieces by Frank, including a sharkskin table and a lacquered screen. As one of the “most famous and influential schemes of decoration of the century,” according to the British art historian and curator Stephen Calloway, it helped put Frank on the international map.

In early twentieth-century France, the field of interior design was dominated by Maison Jansen, a Paris firm founded in 1880 by Dutch émigré Jean-Henri Jansen. Popular among international royalty, Jansen and his staff showed the utmost deference to clients and followed their predilections. Often this meant installing the homogenous Louis period style, heavy in gilt and opulence, which bore no individual designer’s stamp. Frank’s approach, in sharp contrast, resembled that of Maugham and de Wolfe. He offered boldly modern and distinctive interiors, combining elements from diverse artistic traditions and eras and banishing busy wallpapers and damasks, frills and tassels, and superfluous objects. Like those founding mothers, Frank moved in the same social circles as his clientele and presented himself as an unquestionable arbiter of taste whose services were bestowed only by his own choice.

Frank’s career began when, as an ultra-sophisticated and independently wealthy young Parisian, he would help friends with their decorating decisions. In 1921 he undertook what was likely his first official commission, from his school friend Pierre Drieu La Rochelle. The writer (and future Nazi collaborator) had moved into a rented bachelor pad after his divorce. Frank, a twenty-six-year-old with no formal training in art or design, worked on the apartment with an innate assurance and command. After ripping out baseboards, moldings, and cornicing, he painted the walls white and left them without paintings. Furniture was restricted to a wooden table and a large divan in the same dark brown shade. The solitary adornment was an arrangement of flowers in a cuboid glass vase, adapted from a car battery holder he had found. Renouncing ostentation was, of course, its own form of conspicuous snobbery. The writer Maurice Martin du Gard, discussing another of Frank’s early commissions, noted, “Simplicity was becoming fashionable but, in fact, cost the earth.”

Eugenia Errázuriz, a Chilean silver-mining heiress and bountiful patron of the arts, influenced Frank’s ethos of radical simplicity. “Everything I know (more or less),” he said in 1940, “I owe to her.” Born in 1860 in Bolivia, Errázuriz was older than her various acolytes and beneficiaries, among whom the most famous were Picasso and Stravinsky; by all accounts she possessed an unfaded glamour and allure. Picasso characterized her as striking in her beauty, “despite her age and white hair.” In Frank’s opinion, she was ageless. The original minimalist and declutterer, Errázuriz insisted that “elegance means elimination.” Another motto: “Throw out and keep throwing out!” Errázuriz’s apartment on the Avenue Montaigne and her villa in Biarritz were shrines to her religion of anti-vulgarity. Expensive knickknacks, matching furniture, mementos and photographs, and overstuffed rooms were all verboten. Empty space was deemed the ultimate luxury, and cleanliness was key.

This studied emptiness chimed with Frank’s deepest inclinations, and spending time at Errázuriz’s homes affirmed the guiding principles of his calling. His own 3,200-square-foot apartment, in an eighteenth-century building in Saint-Germain-de-Prés, epitomized the philosophy they shared. His niece Alice Frank remembered the unusual yet harmonious amalgam of natural materials in his apartment: wood, marble, leather, straw, and parchment. Each of the ten rooms contained only essential furniture and no pictures or ornamentation save for the occasional, meticulously selected item: a Chinese statuette on the dining room mantelpiece, a wire sculpture of joined hands on the bedroom wall. It was an aesthetic of extreme refinement, an environmental incantation against inner turmoil. The bare walls and dearth of possessions led Cocteau to quip, after his first visit, “Charming young man; pity he was robbed.”

Jarring as such monastic severity was to some, via word of mouth Frank became a highly in-demand designer. By the mid-1920s, “le style Frank” was the last word in chic. He only accepted work that appealed to him, charged exorbitant fees, and brooked little interference. The novelist François Mauriac and his wife were told, their son recalled, that Frank was “willing to design our new apartment so long as we agree to get rid of most of our furniture.” They complied. Also bold enough—and rich enough—was the British shipping heiress, poet, and publisher Nancy Cunard, who moved from London to Paris in 1920. In her seventeenth-century apartment on the Île Saint-Louis, Frank ripped out floors, tiles, fireplaces, paneling, and wallpaper. The sitting room, with its polished cement floors uninterrupted by rugs, was furnished with white leather armchairs and a sharkskin table with iron legs, both of Frank’s own design, alongside an eighteenth-century black desk with a Louis XVI gilt chair. Like Errázuriz, who believed in the enduring perfection of design classics, Frank was faithful to neither antique nor modern pieces but happily mixed them according to his specific vision of what a room required. “The noble frames that came to us from the past can receive today’s creations,” he wrote in 1935. “The house that we build now can welcome ancient things of beauty.”

Frank’s standing as France’s most important interior designer was confirmed in 1926, when his services were engaged by the art patrons Vicomte Charles de Noailles and his wife, Marie-Laure. Rooms in their Place des États-Unis townhouse were photographed by Man Ray and have passed into history as exemplars of Frank’s singular, timeless approach to design. He lined the high-ceilinged salon walls in parchment squares and added bronze doors, a bronze coffee table, quartz lamps, white leather chairs, and a console made of straw, a favored material. In a testament to Frank’s enduring creative legacy, a panel of industry experts in T: The New York Times Style Magazine recently named the Noailleses’ salon one of “The 25 Rooms That Influence the Way We Design.”

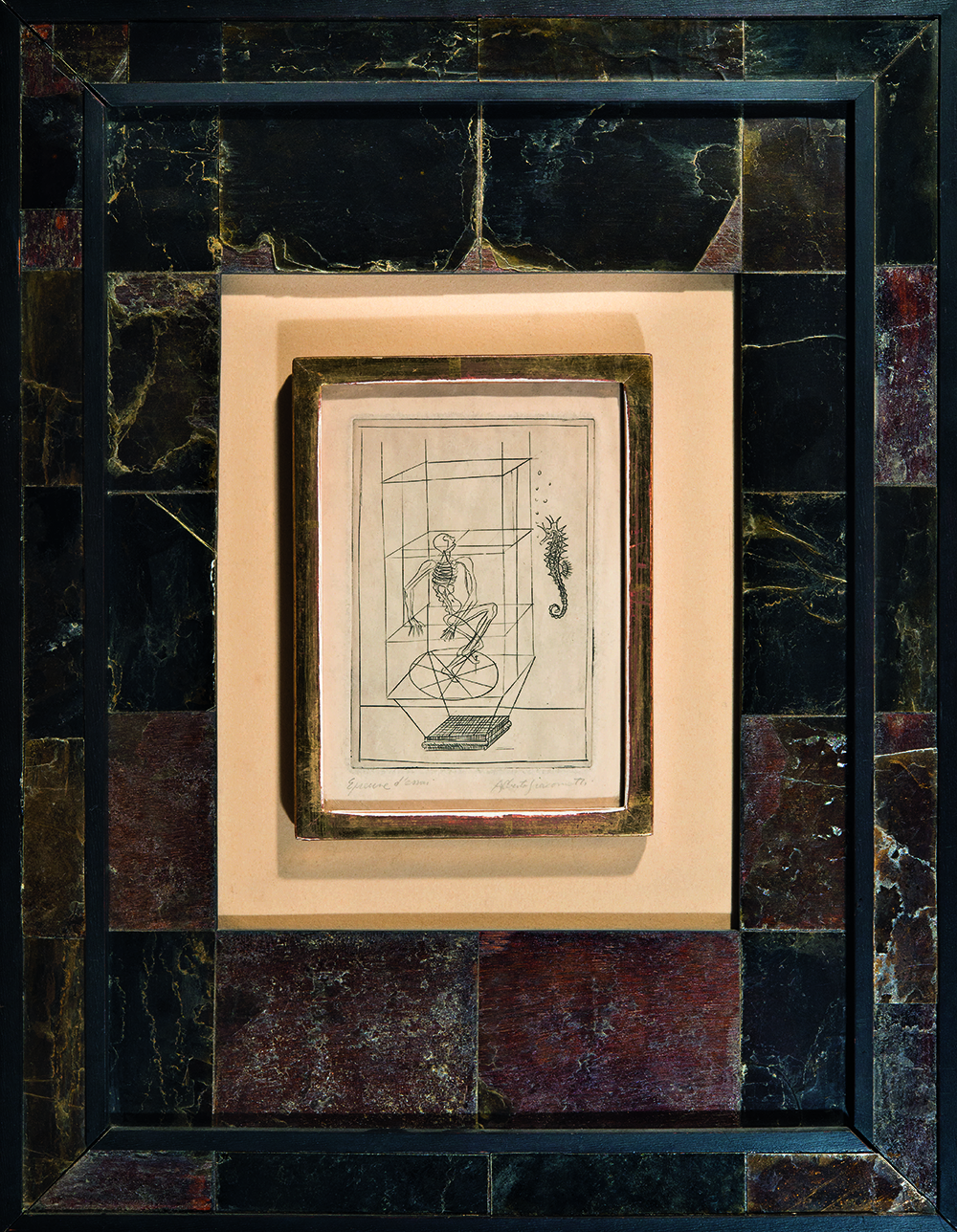

Frank supposedly protested Marie-Laure’s plan to install her extensive art collection. His notorious preference was for at most one or two pictures per room. Mauriac, an artist friend reported, didn’t dare hang his Charles Dufresne watercolors or display portraits of his children. Another client, the mega-rich Argentine industrialist Jorge Born, was forbidden from acquiring Picassos for his Bueno Aires mansion. Incapable of sycophancy, Frank wasn’t cowed by status or celebrity. “Voilà, my work is done,” he’d say upon finishing a job, “now you can start ruining it.” With inveterate precision he oversaw the execution of a room’s every detail, working closely with furniture makers. He also enlisted the talents of fine artists, including Salvador Dalí, Christian Bérard, and Alberto Giacometti, to create objects for the home. (The first version of Dalí’s famous lips-shaped sofa was a commission from Frank.) As Jared Goss has observed, Frank worked in the manner of a traditional French ensemblier, a single artisan responsible for the design, creation, and harmonizing of all elements in a room. The profession flourished in the late nineteenth century and enjoyed a resurgence in the interwar years.

In 1930 Frank formed a manufacturing partnership with the master cabinetmaker Adolphe Chanaux, who was skilled at turning the designer’s rectilinear furniture sketches into reality using luxurious materials, such as sharkskin, vellum, gypsum, and bronze. With Giacometti, Frank collaborated on lamps, sconces, vases, mirror frames, and console tables. Pierre-Emmanuel Martin-Vivier, the author of an invaluable 2008 study of Frank’s life and work, writes, “There was not one social figure, not one intellectual aesthete, to whom Frank did not sell a terra-cotta lamp, a gilt plaster vase, or a patina bronze lamp made by the sculptor.” For Giacometti, the enterprise came at the cost of his surrealist credentials when André Breton abruptly cast him out of the anti-bourgeois, mysticism-steeped art movement. In Breton’s judgment, Giacometti’s biographer James Lord explains, “no true artist would debase his creative powers by devoting them to the production of utilitarian objects.”

Frank would have viewed Breton’s attitude with scorn. “I wish one could more often see artists collaborating in arranging houses,” he once said. “The result would be, at the very least, something of our time, and alive.” He considered his ethereal, transporting interiors legitimate works of art, endowed with art’s power to soothe. “I am deeply convinced,” his biographer Maarten van Buuren said in an interview, “that the ideal of all his design work was to create a space where the soul could go to rest.” The bestowal of order and beauty on the material world as a balm to emotional wounds, as an antidote to painful memories, is an understandable impetus for interior designers. Syrie Maugham grew up in an oppressive religious household, lost three of her younger siblings to diphtheria, and married an abusive older man at age nineteen. In the throes of their contentious divorce, she begged for custody of her furniture: “I cannot be turned out with nothing to make life beautiful and livable even though happiness has gone.” Five years into her equally disastrous second marriage, to the novelist W. Somerset Maugham, she launched her dazzling career. Her rival Elsie de Wolfe endured an unhappy childhood, came of age as a lesbian before the word had even entered common parlance, and was convinced of her own unattractiveness. “If I am ugly, and I am,” she told herself as a young woman, “I am going to make everything around me beautiful.”

Jean-Michel Frank was the last of three sons born in Paris to the German banker Léon Frank, an uncle of Anne Frank’s father, Otto. Léon’s American-born wife, Nanette Loewi, the heiress to a Philadelphia button fortune, was the granddaughter of a Bavarian Reform rabbi and the niece of her husband, though only eight years his junior. While Nanette and Léon’s older sons were strapping and vigorous, Jean-Michel was a small, sickly child, “like a little bird that fell out of the nest,” van Buuren says. From childhood Jean-Michel walked awkwardly, on the balls of his feet, which friends assumed was an attempt to increase his height. But perhaps the tiptoeing indicated a mild disability, such as clubfoot. In a family picture taken when he was around eight, he is leaning on a cane, his right foot in front of the left and its heel several inches off the ground. Even by the solemn standards of early twentieth-century photo portraiture, Jean-Michel’s expression is doleful.

The Frank family lived in elegant style on the grand Avenue Kléber in the Sixteenth Arrondissement, near the Trocadéro Gardens. Jean-Michel attended the prestigious Lycée Janson-de-Sailly, in the same neighborhood. He did not fit in at school. As the writer Jacques Porel recalled in a memoir, his classmate’s “oriental doll looks” and “falsetto voice” invited bullying from students and disdain from teachers. A slightly older Janson contemporary was the novelist Jacques de Lacretelle, who based the titular protagonist of Silbermann on Frank. This Prix Femina–winning novel was published in 1922, before the young designer was well-known. Its harrowing first-person tale, an eloquent snapshot of French society in the wake of the Dreyfus Affair, follows the doomed friendship of two lycée students: David Silbermann, the ostracized son of a Jewish antique dealer, and his Protestant classmate, the narrator. “I sensed in this human being, so different from others,” he recounts, “a persistent and incurable secret sadness, like that of an orphan or a person with some infirmity.” Setting himself apart from the entire school, he pledges abiding loyalty to his strange, vulnerable friend. The other, mostly Catholic students, infected by the resurgent anti-Semitism among their parents and in the French press, find it natural to single out Silbermann for persecution.

They would shove him, snatch off his cap, and throw his books on the ground. Silbermann didn’t defend himself physically but would make a sarcastic remark that more often than not hit home and exasperated his aggressors. Initially, these little verbal victories gave him so much pleasure that he forgot about his detractors and even invited their malice. But I came to realize that he was beginning to suffer as these scenes repeated themselves and as his odd appearance exposed him to a general curiosity.

Silbermann is intellectually precocious and obsessed with literature, as academically confident as he is physically timid. In this Lacretelle didn’t veer far from his model. Frank, whose teenage habit of quoting lines from poetry or plays did little to help him blend in with his peers, always considered Proust his idol and In Search of Lost Time his bible. As for how badly he was affected by his bullies (in Porel’s words, “pimply youths…drunk with brutality”), he stopped attending classes altogether for a few months when he was sixteen, though he successfully sat his baccalaureate exams. “Presumably he was suffering from the anxiety and depression that would afflict him for the rest of his life,” van Buuren writes. As an adult Frank consulted different psychiatrists, chain-smoked, and voraciously consumed cocaine, heroin, and opium, chased by barbiturates. At various points he checked into clinics for drug addiction and nervous collapse, most urgently in 1928, after his mother died. Then aged thirty-three, he was admitted to a rehabilitation facility in Paris, followed by a sanatorium in Vevey, Switzerland. “He had a terrific and desperate inferiority complex,” observed his friend Elsa Schiaparelli, the legendary Italian couturier, “but limitless wit.”

Frank was nineteen when World War I broke out, but his physical frailty exempted him from military service. His father, nervous about his status as an enemy alien, applied for French naturalization. Despite his decades of blameless residence, French-born children, and financial support of French charities, Léon Frank was denied “on the grounds of his German nationality.” In theory, this meant he could have his assets seized or even be placed under arrest. As a German Jew with international banking connections, he was under a double cloud of suspicion even as his older sons, Georges-Ottmar and Oscar, fought for France. In 1915 both were killed on the Western Front within weeks of each other, at ages twenty-seven and thirty-two. Oscar had been married for less than two years and had a baby girl, Alice. Four months later Léon, consumed by grief and bitterness, died by suicide, jumping from the fifth-floor balcony of the apartment. His widow, Nanette, sank into a deep depression and was admitted for psychiatric treatment, the first of many such stays.

After the war, Frank had a short stint working in banking. But though he had studied law like Oscar before him, he must have known he wouldn’t settle into the family business. He didn’t need a salary, having inherited a fortune from his father. The inescapable theme of Frank’s existence—that he was equally cursed and blessed—came into stark relief at the dawn of the 1920s. He had already endured more sorrow and bereavement than most people face in a lifetime. But he had survived to find himself young, talented, rich, and free, living in Paris at a uniquely fertile time for artistic, social, and political radicalism. As the writer Philippe Soupault put it in 1923, “What mattered was being modern, the new spirit was all anyone spoke about.”

No longer the outcast of his younger days, Frank was part of a cultured social set with his school friends Léon Pierre-Quint—a novelist, publisher, and Proust’s first biographer—and the surrealist writer René Crevel, Frank’s partner in cocaine-fueled nightclubbing. Sometimes they would be joined by Tony Gandarillas, Eugenia Erràzuriz’s gregarious diplomat nephew who had a passion for art and opium. After the horrors of war, a reckless euphoria was in the air, as well as an infectious sense of creativity. For a while Frank was a leisured aesthete, an avid consumer of novels, films, plays, and art exhibitions. But soon his own artistic impulses, stimulated by the collective drive to remake the world anew, found expression in refashioning his friends’ homes in a manner that befitted the zeitgeist. At the time surrealism, with its mandate to tear down convention and liberate imagination from all restraints, was burgeoning; Frank’s early engagement with the movement set the scene for his collaborations with Dalí, Giacometti, and Bérard. The gifts of fine artists being deployed in the home, despite André Breton’s distaste, was itself revolutionary.

During this period Frank also traveled to the Riviera, Spain, and Italy. One memorable trip occurred in the summer of 1923, when he left Paris for Capri with his friend Mireille Havet, a devoutly bohemian poet and protégée of Guillaume Apollinaire. On the Neapolitan island, to her mind the motherland of “poets and inverts,” they socialized with the Russian painter Aleksandr Yakovlev, who had a studio there, and the pianist Misia Sert, an intimate of Coco Chanel. The exiled gay French writer Baron Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen, who had built a neoclassical villa on a hilltop above the ruins of Tiberius’ palace, invited Frank and Havet into his custom-designed circular opium den and supplied them with enough of the drug to last for weeks. Away from France, surrounded by nature and the relics of ancient history, Frank found he could forget the pain of his own past. His designs would always bear traces of his surroundings that summer: airy whitewashed villas, natural tones of terra-cotta and marble, classical curves and symmetry, a becalmed air, and a sense of past and future seamlessly merging.

The Jean-Michel Frank boutique at 140 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, which opened in March 1935, sold furniture, lamps, screens, and mirrors and operated as a front office for his interior design business. Van Day Truex, the American artist, designer, and Parsons School of Design president, knew Frank during this era. In a 1976 article for Architectural Digest, Truex remembered him as “a charged dynamo with a deep, gravelly voice. He was positive and vital, like a vibrating high-tension wire, yet highly sensitive and prone to periods of black depression.” One such period occurred in the summer after the shop launched, when Frank’s dear friend René Crevel committed suicide. Crevel lost his father to suicide at age fourteen, was conflicted about his bisexuality, and suffered from tuberculosis, self-medicating with morphine. Crevel’s death so upset Frank that Dalí feared he would kill himself, too.

Despite Frank’s precarious mental health, not to mention the financial shock waves of the Great Depression, he thrived professionally in the 1930s. In December 1933 his grandly conceived music room in Cole Porter’s Paris apartment, featuring a silver ceiling, black lacquer arches, and a black marble floor, was featured in French Vogue. Schiaparelli, a loyal friend to Frank since her move to Paris in 1922, had him design two of her homes and, in 1934, her new headquarters and boutique at 21 place Vendôme (where it remains). Across the square was the Guerlain store, which Frank designed in 1935 along with L’Institut Guerlain, the perfumier’s beauty salon on the Champs-Élysées, as well as Jean-Pierre Guerlain’s apartment.

Frank’s romantic life also prospered in this decade: in 1933 he began seeing William Thaddeus Lovett, a nineteen-year-old blue-eyed American newly arrived in Paris. They went on a series of idyllic vacations to the Villa d’Este on Lake Como and to the rest of Italy, to Belgium, to the South of France, and to Hammamet, Tunisia, a popular destination for pleasure-seeking artists, writers, and actors of the day. Frank’s friends, who found Lovett amiable and easy on the eye, accepted him into their clique. He proved helpful when it came to charming American clients: in the boutique, he sold the New York fashion magnate Hattie Carnegie 45,000 francs’ worth of goods, equivalent to well over $100,000 today. And Lovett coped well with Frank’s volatility, his black moods and drug use. It was “the strange union of a disenchanted German Jew, ‘dark, baroque, effeminate,’ and a Methodist Yankee as blond as an Aryan,” Laurence Benaïm, Frank’s French biographer, writes. She is quoting a description of the young Frank by Jacques Porel, who claimed in his memoir that the anxious teenager “dreamed of being” a blond, athletic, English type. As unlikely as Frank and Lovett’s coupling may have seemed, they remained together until separated by the war.

The outbreak of war changed everything for Frank and his circle. He was in the middle of an important job, designing a floor of Nelson Rockefeller’s Fifth Avenue triplex, when his business partner Adolphe Chanaux was conscripted, along with most of their staff. The furniture workshop closed. The boutique stayed open, but there were few customers. In June 1940 Frank prepared to leave the country as the Germans advanced. With Lovett, he headed to Bordeaux, where they encountered one of World War II’s great civilian heroes: Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the port city’s Portuguese consul who defied his government’s orders and gave thousands of visas to those fleeing fascism. Thanks to Sousa Mendes, Frank and Lovett received visas for Portugal, as did Salvador and Gala Dalí. The group sailed to Lisbon and met up with other exiled Parisians, including Schiaparelli and the novelist Julien Green, an old friend of Frank’s who found him “both cheerful and desperate.”

After a few weeks in Lisbon, Lovett went home to the U.S. and Frank obtained a visa for Argentina. His plan was to get to the U.S. as soon as possible, but at least in Buenos Aires he would have a social network and a distinguished professional reputation. On his arrival, he moved into a small downtown apartment and was warmly welcomed by his client Jorge Born and the interior designer Celina Aranz. Aranz’s husband, Ricardo Pirovano, owned a classic-modernist furniture and decorating company, Comte, with his brother, Ignacio. The Pirovanos, who were related to Errázuriz on their mother’s side, had always been inspired by Frank’s work and both imported and reproduced his pieces. Now Frank began working directly with them. In particular, Aranz said, “He modernized and simplified classical French and English designs to the taste of local society.”

Ever the perfectionist, Frank spent time sourcing the exact South American pearwood he required, and he’d get up early to negotiate for the best hides at the cattle market. Yet keeping busy couldn’t mitigate the psychological toll of deracination, of the knowledge that his beloved Paris was in the hands of barbarians, and that Jews in Europe, including his relatives, were in dire peril. Aranz remembered that Frank, during those months in late 1940, was prone to spells of depression and reclusiveness, especially “after terrible scenes, by phone, between him and his American lover.”

Eventually Frank managed to get an American visa and set sail from Brazil, arriving in New York City in mid-December 1940. It’s unclear if he planned to put down roots in the U.S. As far as his friends in Buenos Aires were concerned, he was only planning to be away for three months. But his return may have depended on Lovett, from whom he’d been separated for nearly six months. Alas, the young American had met someone else. Frank was alone in a city he found alienating, short of money, during a freezing cold winter, his heart and his spirit broken. Schiaparelli, who had managed to visit Paris and return to New York, told him that the Vichy government was seizing Jewish-owned businesses and forcing Jews to declare their assets. For Frank, after his father’s experience during World War I, history was repeating itself. Naturalized French Jews, who included Frank, were being stripped of their citizenship. He was effectively stateless.

The night Frank died, Manhattan was besieged by one of the worst blizzards ever to hit the city. Eighteen inches of snow fell in Central Park. Three blocks away, in a bedroom on 63rd and Lexington, the forty-six-year-old swallowed enough allobarbital to empty the bottle. His body, dressed in pajamas, weighing only 135 pounds, was discovered on the morning of March 8, 1941. A suicide note written in perfect English, its script neat and forward slanting, declared: “I do this for no reason but ill health. I ask all my friends who have been so good to me to forgive me. I thank them deeply for trying to help me, but I have no strength to go on. I am too ill.” His careful words didn’t stop people blaming Lovett’s rejection. “I imagine he committed suicide because of that American friend,” the Argentine writer Victoria Ocampo wrote to a friend. “Drieu had long feared it might happen.” Yet in 1930 Frank had insisted, in a letter to his old friend Léon Pierre-Quint, that “no sadness in the world” could have led to his “lamentable despair…the reason I am forced to suffer all this is that I am ill, physically ill.”

A long-prevailing myth was that Frank leapt to his death from a high window, like his father a quarter century earlier. It was Maarten van Buuren who read the autopsy report and death certificate and established cause of death as “acute suicidal barbiturate poisoning.” Not that the sensationalizing of Frank’s suicide assured his place in posterity. In the decades after World War II, his work was known and appreciated by only a few dedicated fans. It was in the 1970s that connoisseurs and collectors, notably Yves Saint Laurent, rescued Frank from obscurity. By 2006 the market for his pieces had “exploded,” a specialist from Christie’s New York told a journalist. Last May, at Sotheby’s Paris, the bidding on a pair of his sharkskin-covered armchairs, circa 1928, tripled the estimate to reach €1,572,500. Around the same time, Assouline published a lavish coffee-table book on Frank, billing him as “an iconic yet somewhat mysterious artist whose work illuminated the decorative arts in the twentieth century.”

Laure Verchère’s Jean-Michel Frank, with an introduction by Jared Goss, features two hundred illustrations, including a two-page spread of Rockefeller’s apartment, one of Frank’s last major projects. With its gloriously colorful and upbeat scheme encompassing buttercup-yellow sofas, an abstract floral rug by Christian Bérard, and a mural by Matisse, the room demonstrates a progression away from the designer’s signature sobriety and simplicity. No longer wedded to what Cocteau called “the invisibility of true elegance,” Frank had allowed some fun and gaiety to expand his creative purview, late on in a too-short career that, nevertheless, serves as an object lesson in Proust’s maxim “Everything great in the world comes from neurotics. They alone have founded our religions and composed our masterpieces. Never will the world know all it owes to them nor all that they have suffered to enrich us.”