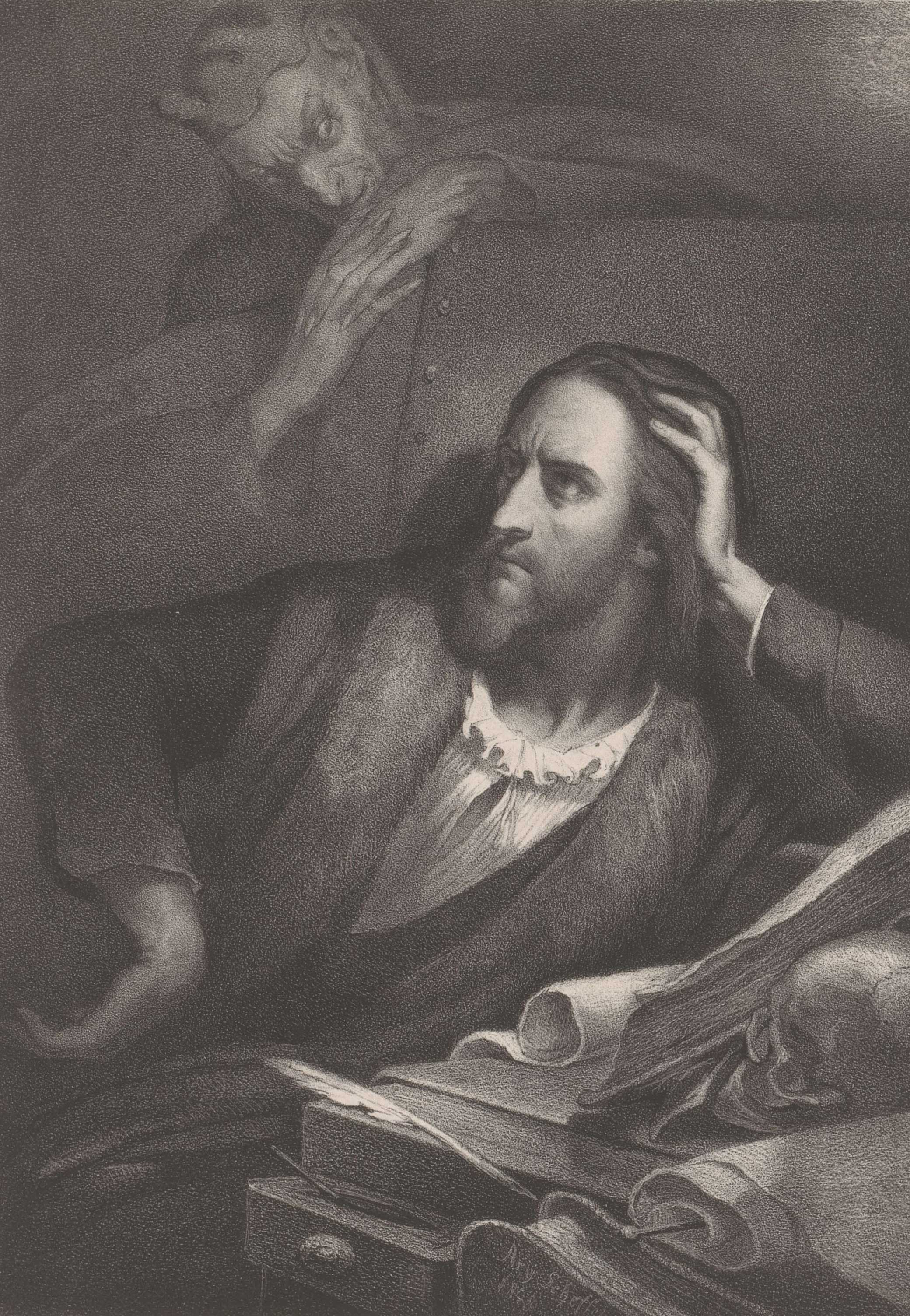

Faust in His Study, by Johannes Christiaan d’Arnaud Gerkens after Ary Scheffer, nineteenth century. Rijksmuseum.

Either a legion of demons or an unfortunate explosion killed the necromancer Johann Georg Faust while he worked on some alchemical experiment, perhaps attempting to find the philosopher’s stone or inscribing magic circles to conjure this or that demon, but it’s not clear just when this happened. Of the great magicians of the Renaissance—Paracelsus, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, John Dee—Faust is arguably the most famous, even though he’s the figure historians know the least about, more shadow burned on the library floor than actual man. Forever associated with the demon Mephistopheles, the intermediary of Satan with whom Faust signed his diabolical contract to acquire secret knowledge and supernatural abilities, the ill-fated sixteenth-century German occultist has given us the phrase Faustian bargain, denoting any deals with the devil, literal or figurative. Historian Leo Ruickbie estimates in his 2009 book Faustus: The Life and Times of a Renaissance Magician that since the sixteenth century around twenty thousand books have fictionalized the notorious bargain.

Though his is the most infamous of satanic contracts, Faust’s was hardly the first nor the last. Rumors of such contracts were replete during Faust’s day and back into antiquity. Some of these legendary contracts were signed with devilish agents of Lucifer, others with Satan himself, but all have at their narrative apex that cursed moment when the protagonist is willing to part with their soul for something else of value. During the early modern period, such contracts were strongly associated with witches, the signing of (typically) a woman’s name into the devil’s book signaling the start of her indentureship to the prince of darkness. Drawing on the authority of the Dominican friars Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger’s fifteenth-century Malleus Maleficarum, both Catholics and Protestants came to believe in cabals of women who sold their souls to Satan in deals finalized with grotesque sexual acts, a paranoid and misogynistic libel that ultimately led to the persecution and murder of hundreds of thousands of people.

The earliest versions of the legend concern the sixth-century cleric Theophilus, who sells his soul in exchange for worldly power only to be redeemed later by the Virgin Mary (and canonized by both the Orthodox and the Catholic Churches). Rumors of demonic bargains dogged numerous medieval personages, including Sylvester II, the twelfth-century reform-minded pope; the eleventh-century Icelandic priest Saemundr Frode Sigfússon; and the anonymous thirteenth-century Czech scribe who allegedly conspired with a demon to complete an entire illuminated manuscript in a single night, the result being the four-foot-tall Codex Gigas.

Signing the dotted line didn’t become less popular after Faust. The seventeenth-century libertine priest Urbain Grandier, known for his orgies at the convent of Loudon, finalized a contract with several different demons (there are still extant copies, though the handwriting certainly looks human); an eighteenth-century member of the New Hampshire militia named Joseph Moulton sold his soul for unlimited gold coins; and the blues guitarist Robert Johnson went down to the crossroads of Highways 61 and 49 in Clarksdale, Mississippi, to acquire his prodigious talent. All of these stories are distinct, of course, and come from different time periods and cultures with characters who have disparate motivations and failings, but fundamentally what they all tell is a universal story about the perils of hubris pushed to a singular extreme.

So common is the trope that narrative theorists even have a numerical identification for it. According to American folklorist Stith Thompson’s 1932 Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, any narrative in which a “man sells soul to the devil” is classifiable by the taxonomic number M211. Under that rubric you can find Stephen Vincent Benét’s short story “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita, Roman Polanski’s film adaptation of Ira Levin’s novel Rosemary’s Baby, and Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” Faust has become the archetype, and an archetype can’t be a man—yet Faust was a man, albeit a specter, a shadow, a stranger whose name appears in earlier iterations of the legend. There is Thomas Mann’s experimental composer in his 1947 novel Doctor Faustus. Before that there was the protagonist of the French composer Hector Berlioz’s 1848 opera La damnation de Faust. Just a few decades earlier the titular Romantic hero of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s play Faust appeared.

And then there was the English playwright Christopher Marlowe’s rendition of Faust and his demons, which first elevated the myth to literary trope. So notorious was The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus that when the play premiered in 1592, rumor had it that the devil himself was in the audience to make sure that he was presented fairly, and that the stage incantations led to the conjuring of an actual demon among the actors. In the play Faust hears Homer and sees Helen of Troy, but they are phantoms: “Rather illusions, fruits of lunacy / That make men foolish that do use them most.” As in most variations of the legend, Marlowe’s Faust gains all sorts of supernatural abilities from his devilish agreement: invisibility, levitation, conjuration. Most importantly, however, Faust acquires knowledge—specifically the forbidden variety. Already abundantly learned, this version of Faust has grown tired of philosophy, medicine, and theology. “Is to dispute well, logic’s chiefest end? / Affords this art no greater miracle?” he moans. The tragedy of the play is that the necromancer believes such chimeras are worth more than his eternal soul. We’ve retold the story of Faust for five hundred years, but he’s become as much a phantom as those specters in the play. Today the real man is mostly only as tangible as the knowledge that he existed.

There was an alchemist known as Faust who Latinized his name to Faustus. He may have been christened George Sabellicus. Most everything else is conjecture, invention, or mere possibility. Maybe Faust was from Heidelberg, or Knittlingen, or Roda; maybe born of (in some accounts a virgin) woman in 1466 or, based on good evidence, in 1481. The character could have developed over time as writers confused two itinerant magicians with the same name. Dozens of grimoires and diabolical books of incantations and conjurations claim him as their author, but all of them are elaborate forgeries compiled after his death. During his lifetime, he was already notorious for supposed acts of conjuration and necromancy, and yet four centuries later the devil’s contract is the most characteristic part of Faust’s biography, the one thing that everybody knows, even though that detail is a later interpolation.

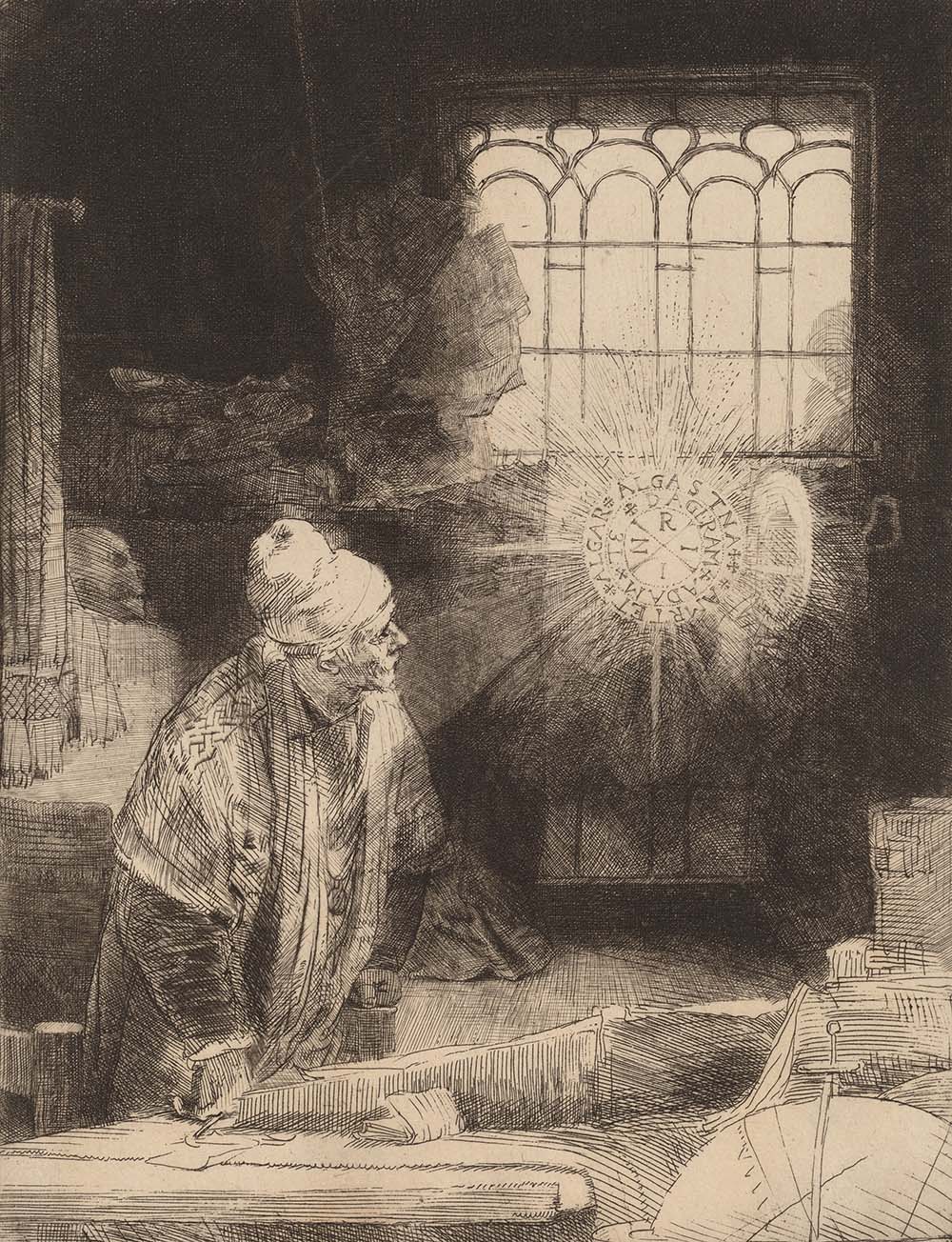

Faust was plying his occult trade at a time when a certain type of elite occultism was respectable among some scholars. Casting demons and conjuring specters wasn’t unusual (or at least belief in such things wasn’t out of the ordinary) during the Renaissance, an era that for all of its connotations of rebirth was more a golden age for academic magic than it was for enlightened science. “Magic was a dominating factor,” writes historian Frances Yates in The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, “working as a mathematics-mechanics in the lower world, as celestial mathematics in the celestial world, and as angelic conjuration in the supercelestial world.” Intellectuals studied the Jewish mysticism of kabbalah as well as the neo-paganism of the mythical Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, practicing the manipulations of spells, the drafting of magic circles to imprison spirits, and divinatory calculation with strange glyphs. At the time Faust was not the most prominent of these wizards, but he was soon to become the one who was most synonymous with the dark arts.

The narrative Marlowe primarily relied on for his early rendition of the Faust myth is Das Faustbuch, or The Faust Book, printed by Johann Spiess in Frankfurt in 1587 and possibly written by him as well. It was a volume designed to entertain, edify, and help readers to “protect themselves from similar maculations of the most shameful sort.” In bright red gothic print, the frontispiece announces that this authoritative account was written some four decades after Faust had either been killed in an alchemical experiment or dismembered by visitors from hell—the manner of death depends on whose authority you trust.

Ruickbie notes that Satan may have come to collect his due on several different dates between 1538 and 1541. Certainty on where the magician met his doom is also a matter of disagreement, although that inconvenient fact hasn’t stopped proprietors of half-timbered taverns and inns from the Alps to the Baltic from showing off bloodstains of mysterious vintage to eager tourists, conjuring gothic images of Faust’s flesh being peeled from muscles, ligaments twisted apart, bones snapped, and eyes gouged. A massive compendium of the legend’s variations compiled by the German philosopher Alexander Tille in the nineteenth century lists fifty separate potential locations for the murder, including a village in Baden-Württemberg (a popular candidate), as well as Regensburg, Wittenberg, Cologne, and Königsberg.

Regardless of the when or the where of Faust’s demise, most compilers of the lurid pamphlets known throughout the German-speaking lands of the Holy Roman Empire as teufelsbücher, or Devil’s books, were clearer on the how, if equally unable to limit themselves to one explanation. Teufelsbücher constituted a genre of quickly and often anonymously written pamphlets that promulgated moralizing and prurient accounts of demonic affairs. Dozens of titles were produced by German printing presses in the second half of the sixteenth century, providing the raw materials for the Faust legend. In a 1548 tract Johannes Gast writes that Faust was “allotted a miserable, lamentable end, for he was suffocated by Satan,” while in a 1555 sermon the theologian Philipp Melanchthon described how after a night of unnatural shrieks and rumblings a group entered the magician’s chamber to find that demons had “twisted the dead man’s face against his back.” The anonymous English translator of a German account, known only as “P.F. Gentleman,” provides a far more detailed account: Faust’s eyes are found in opposite corners of the room, his teeth in a pile of horse shit and his brains, which once comprehended divine secrets, are smeared across the wall. Despite variations on the where, when, or how, there is consensus on the why—somebody can’t be expected to deal with the devil for that long and to get away with it.

The life Faust lived before his death was also ripe for imaginative speculation, often married to details drawn from much older sources. Melanchthon claimed that Faust had flown over Venice before crashing near St. Mark’s Square. The preacher knew that his audience would connect Faust to a far more ancient magician, the arch-heretic Samarian Gnostic wizard Simon Magus, who in the first century engaged in a flying battle with the apostle Peter over Rome before falling to the earth (he died). Gast, who admits to never having met Faust, notes in his 1548 Convivales sermones that the necromancer “led a dog and a horse, I believe them to have been demons…The dog sometimes assumed the likeness of a servant,” while making clear that this was simply what “I was told.”

Faust first enters the record in 1507, when the Benedictine abbot and occultist Johannes Trithemius briefly, but memorably, eviscerates him in a letter to the mathematician Johannes Virdung. Trithemius refers to the magician as the “prince of necromancers,” a “vagabond, an utterer of vain repetitions, and a wandering monk who, lest he have the temerity to profess further in public places things so abominable and contrary to the Holy Church, is deserving of chastisement by whips.” The Benedictine also had a reputation as a necromancer, which clearly didn’t result in any kind of feelings of sympathy for Faust—or perhaps just made him anxious that Faust was denigrating the vocation with his darker pursuits.

During the sixteenth century there are glimmerings of Faust here and there—a sighting in Prague, an account in Krakow, an incident in Wittenberg. Martin Luther discusses him in the charmingly titled collection Table Talk; it is the first time Faust is connected to the trope of an infernal contract trading his soul for supernatural powers. In 1513 Trithemius’ friend Conrad Mutianius Rufus, a humanist scholar, encountered Faust while they were both staying at a Thuringian inn and mockingly dismissed the magician as the “demigod of Heidelberg.” By 1535 accounts put Faust near Münster during the infamous Anabaptist rebellion, when religious radicals abolished private property and mandated Old Testament law while establishing a communist theocracy. Defeated by a combined force of Lutherans and Catholics led by the latter’s bishop (the first ecumenical partnership), Anabaptist leaders were burned at the stake; John of Leiden’s corpse was exhibited for five decades in an iron cage hanging from the steeple of St. Lambert’s Church. As for Faust’s role, the Waldeck Chronicle by Daniel Prasser, written around 1650, records that the magician entered the Catholic encampment and promisingly prophesized to all those assembled that “without doubt, the city of Münster would be captured by the bishop that same night.” Münster’s ensuing collapse reverberated throughout Christendom. From the ashes of Münster arose the heretical sect of the Familiasts, an occult group that in the following generation embedded itself in royal courts from Philip II of Spain to Elizabeth I of England. Faust’s association with Münster makes some sense, even if Prasser indicates that the devilish contracts happened not with the religious radicals who would become the Familiasts but rather on behalf of the conservative status quo that defeated the revolution.

No one can agree on what to make of Faust, but the making of him has been an obsession of many for centuries, especially after the association of the good doctor with the trope of an infernal bargain made its way across the North Sea and into Marlowe’s celebrated play. I’d suggest that the connection persists because of our innate attraction to the other central character across the Faust corpus: Mephistopheles. While many early narratives about the magician attribute the contract to Satan himself, in Spiess’ Faustbuch the devil instead employs that unique emissary. Historian Jeffrey Burton Russell explains in his 1977 book Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World that his titular subject is “not a traditional Judeo-Christian or folkloric name but a brand-new coinage,” sounding a bit Greek or Latin and perhaps trying to evoke Hebrew as well. Several different etymologies are offered, with elements of the name recalling the Latin mephitis, meaning “sulfurous,” or the Hebrew tophel, for liar. Mephistopheles is a singular and untraceable entity. Russell concludes that the “originator and his intentions are unknown, so the derivation of the name is uncertain”—unless of course that just happens to be the demon’s actual name.

Mephistopheles bears a cool, detached, almost ironic affect. When the demon first appears in Marlowe’s play it’s in the form of a decomposing corpse, with maggots crawling out of his nostrils. Marlowe’s Faust compels Mephistopheles to return in a more pleasing form, and so the demon comes back wearing the cowl of a Franciscan mendicant. “Hell hath no limits,” explains the demon, “nor is circumscrib’d / In one self place; but where we are is hell, / And where hell is, there must we ever be,” whether in Krakow or Heidelberg, Prague or Wittenberg. If Faust was once a real man, then through the alchemy of cultural transmission and the theurgy of narrative he has become as untraceable as the demon whom he sold his soul to, a creature just as mysterious and otherworldly.

A man who has been transformed into a legend must speak in a powerful enough register for us to still hear him more than five centuries later. Should Faust’s story have any enduring resonance, it’s that his legend is about misjudging the value of ephemeral things and, in the process, losing eternal ones. It’s about the difference between appearances and reality. In a disenchanted age both he and his demonic interlocutor become an “elegant symbol of the modern,” as Russell writes—not some remnant of a superstitious medieval past, but rather an embodiment of the era of rampant individuality and intellectual selfishness that was inaugurated with modernity and continues to serve as the setting for all new renditions of this old myth.

Faust’s story is ultimately about the burdens of artifice, about the risks of confusing constructions for reality, desires for necessities, power for responsibility, approval for dignity. The curse is that this living man accrued so many stories about himself that he transitioned into legend, myth, symbol and in the process erased the particulars of his soul. Now the imagined Faust is the real Faust. If you search for him, then he is already here. Take heed.