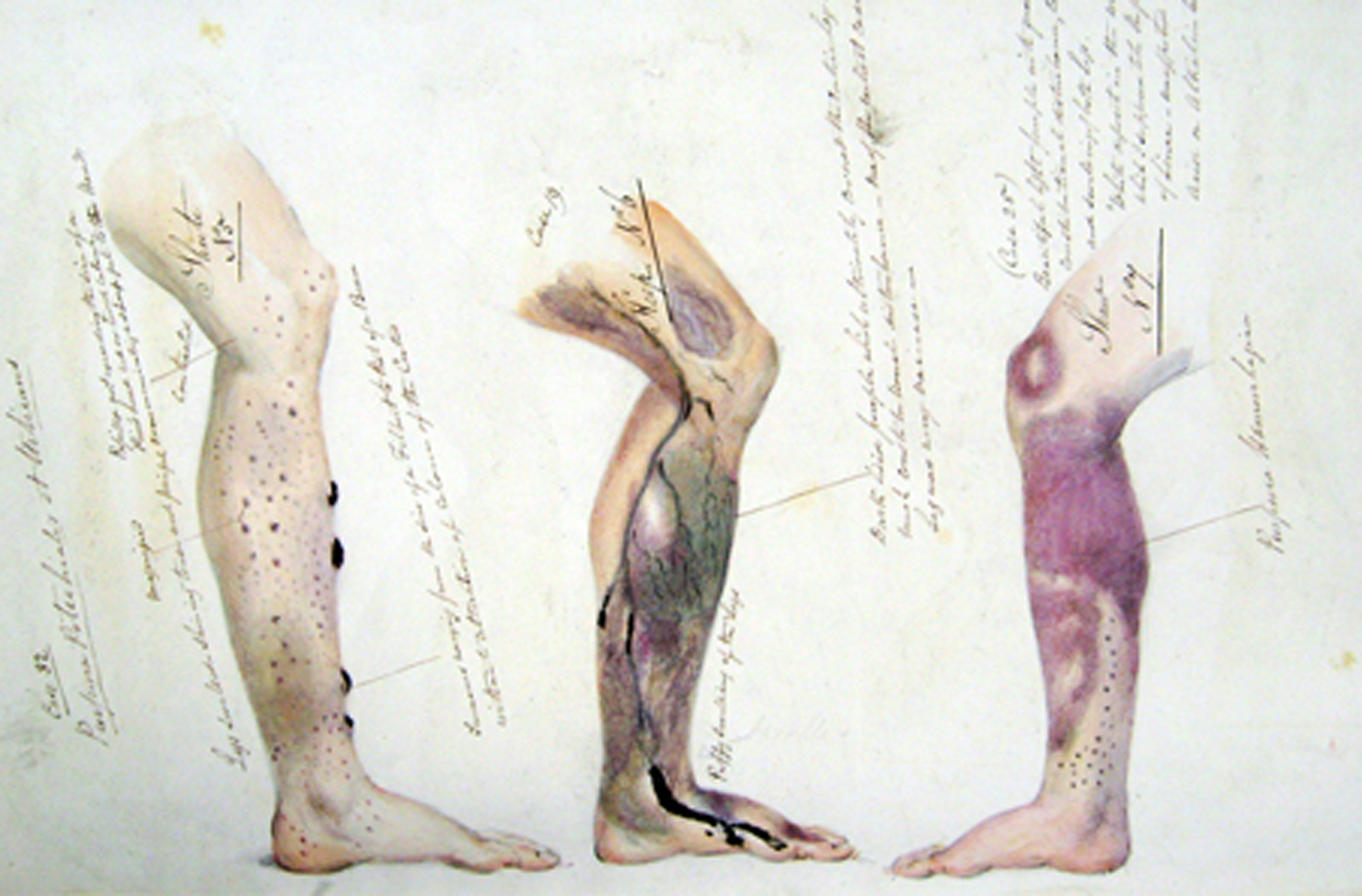

Page from the journal of Henry Walsh Mahon showing the effects of scurvy, from his time aboard HM Convict Ship Barossa, c. 1840. The National Archives, UK.

The shore of Amsterdamøya feels like one of the most remote places on Earth. A small island on the northwest edge of the Arctic archipelago Svalbard, Amsterdamøya’s beach looks back towards the archipelago and its main island, Spitsbergen, sheltered by a small hill that is all that stands between you and the Arctic Ocean. Down the beach were three walruses, lolling in the sun, unconcerned by our presence. We meant them no harm, of course, but even still, they had some reason to be unbothered by us. Humans can be efficient, highly devastating predators, but we can also grossly underestimate our prey on occasion, and watching them I thought of Elisha Kent Kane, arctic explorer whose ship was ice-bound off Greenland in 1853 for two years, the result of a failed hunt for the missing Franklin Expedition that led to desperate times and three deaths. When they learned at one point that there were walrus nearby, the ravaged and hungry sailors set out to kill a few. “We saw at least fifty of these dusky monsters, and approached many groups within twenty paces,” Kane later wrote. “But our rifle balls reverberated from their hides like cork pellets from a popgun target, and we could not get within harpoon distance of one.”

We weren’t here to hunt, of course; I was there as part of an artist residency, The Arctic Circle, which takes a group of artists, writers, and scientists around Svalbard in a three-masted sailing ship, the Antigua. For two weeks in June we sailed through an endless day up the coast of Svalbard to its northern fjords; we had been on our way from Magdalenafjord to Sallyhamna when heavy fog obliged us to anchor near Amsterdamøya, where we now stood downwind from the peculiar stench of walruses.

They weren’t the only noteworthy aspects to the beach of Amsterdamøya: what was odd about our landing site was, even though it’s about a thousand kilometers from the Arctic tree line, there was wood everywhere. Most of the beaches in Svalbard are barren save for small jagged rocks pushed forward and left behind by glaciers. But on Amsterdamøya one finds wood of all sizes, from small scraps to ten-foot logs. Half of it is driftwood, carried an unimaginable distance from the mid-Atlantic by Gulf Stream (not just wood, but also trash, not as plentiful but no less noticeable). The driftwood can be gathered and used for firewood, but anything that has a nail in it—or is otherwise worked by human hands—can’t be removed from the beach by order of the government. These are the remains of the once-thriving temporary settlement, Smeerenburg.

It was on the shores of Amsterdamøya that Svalbard entered human consciousness, when Willem Barents landed here in June of 1596, claiming the archipelago for the Netherlands. Looking around at the glacier-carved peaks around him, he named what he found Spitzbergen (literally, “pointy mountains”), then sailed onward, eventually making it to another arctic archipelago, Nova Zembla, where he and his crew spent a brutal winter that killed Barents and three of his crew.

Almost twenty years after Barents, Robert Fotherby landed here, and in 1614 claimed for England the nearby bay Magdalenafjord, which he called “Maudlin Sound.” Fotherby’s and other reports of the area recorded vast numbers of whales, and within a few years the whalers descended on the Greenland Sea. They came here to hunt right whales, so named because they were the “right” ones to kill: slow moving and so full of blubber that they’d float to the surface after death.

The twin heritage of the Dutch Barents and the English Fotherby may have played a part in the bitter rivalry that would ultimately develop between the two countries over whaling rights off of Svalbard. While other countries, including Denmark, France, Spain and Germany all whaled in the seas between Greenland and Svalbard, it was England and the Netherlands that engaged in a brutally hostile competition. At the end of the season, English sailors would board the Dutch ships by force, confiscating the season’s worth of whale oil, along with any equipment on board; the next year, retaliating Dutch ships would return the favor.

Smeerenburg—literally “blubber town”—was built during this period. Eventually, whalers would learn to boil whale fat on ships, a process described in Chapter 95 of Moby-Dick, “The Cossack”:

That office consists in mincing the horse-pieces of blubber for the pots; an operation which is conducted at a curious wooden horse, planted endwise against the bulwarks, and with a capacious tub beneath it, into which the minced pieces drop, fast as the sheets from a rapt orator's desk. Arrayed in decent black; occupying a conspicuous pulpit; intent on bible leaves; what a candidate for an archbishopric, what a lad for a Pope were this mincer!

But that technique would come later; in Svalbard’s heyday as a whaling center, the boiling had to be done on land in large copper kettles. Scattered around the beach at Smeerenburg are still the remains of these blubber ovens: the copper kettles are gone, but the small mounds on which they rested are still visible, covered with rich lichen. They are invariably greener than the land around them, since those decades of blubber driveling into the ground even centuries ago deposited noticeably more nutrients in this barren land.

At its height, Smeerenburg was more than just these pots; a rudimentary town evolved over time, including over a dozen buildings and an elevated wooden walkways between buildings, for when the spring melt deluged the beach with water. That whalers were able to construct something this elaborate in land so distant should have been enough in and of itself, but over time, the legend of Smeerenburg outgrew even these modest feats. Reports erroneously described it as a bustling metropolis complete with bars, hotels, and brothels. Fridtjof Nansen described it in 1920 as

a complete town with stalls and streets, 10,000 people during the summer with the noise of various stalls and train-oil boilers and gambling dens, of smithies and workshops, of dubious shops and dancing joints. Along this flat beach there were crowds of boats with sailors who arrived from the exciting whaling chase, and of women in gay colors who were out to catch men.

In reality, Smeerenburg was usually abandoned at the end of each season, though by the 1630s, years of vicious competition led Dutch whalers to try something novel: leave a crew of volunteers to overwinter at Smeerenburg, both to be on hand to protect more expensive equipment that could be left behind, and in order to get the whaling station up and running as soon as possible the following spring. And so in 1632 seven men were left in Smeerenburg to wait out the winter.

It did not go well. The Dutch volunteers quickly succumbed to the “polar night disease,” as it was sometimes known—scurvy. As related by Kenneth C. Carpenter, in his A History of Scurvy and Vitamin C, “They were left on September 11, and already by November 24, ‘the scurvy began to appear among them; they searched very earnestly for green herbs, bears and foxes, but could find none,’ nor did they have any success later. Several of them took ‘potions against scurvy,’ but three of them died in mid-January, and the rest were too weak even to try to hunt for fresh meat. All were dead by the end of February.”

We tend to think now of scurvy as mainly a punch line, if anything—“scurvy-ridden rats” is the kind of popular pirate epithet that appears in even the most G-rated family fare. Partly this is because now, fully understanding its mechanism, it seems a particularly ridiculous problem. But ask anyone whose suffered from it: it is a singularly horrid and terrible way to die. In 1602, a Father Antonio de la Ascension chronicled with particularly gruesome detail the onset of the disease in his party while in California:

The first symptom they notice is a pain in the whole body which makes it so sensitive to touch…After this, all the body, especially form the waist down, becomes covered with purple spots larger than great mustard seeds. Then from this bad humour some strips or bands come behind the knee joints, two fingers and more wide like wales….These become as hard as stones, and the legs and the thighs become so straight and stiff with them that they cannot be extended or drawn up a degree more than the state in which they were attached….The sensitiveness of the bodies of these sick people is so great that…the best aid which can be rendered them is not even to touch the bedclothes…the upper and lower gums of the mouth in the inside and outside the teeth, become swollen to such a size that neither the teeth nor the molars can be brought together. The teeth become so loose and without support that they move while moving the head…. With this they cannot eat anything but food in liquid form or drinks,… they come to be so weakened in this condition that their natural vigor fails them, and they die all of a sudden, while talking.

French sailors mired in ice near Montreal in 1536 performed an autopsy on one of their crew, and discovered his “heart was completely white and shriveled up…[and] his lungs were very black and gangrened.” Francois Pyrard, a mariner who kept a journal while on board ships bound for the East Indies in 1602, likewise recorded that

While we were at the Island of St. Lawrence there died three or four of our men of this malady, and when their heads were opened all the brain was found to be black, tainted, and putrefied. The lungs become dry and shrunk like parchment that is held near the fire.

Another French sailor almost a hundred years later recorded how “the parts affected become insensible, blackish, and, when one touches them, there remains a hollow such as one would make in a piece of dough.

Those who didn’t die from the disease were overcome with lethargy, barely able to move or eat. The Norwegian explorer Jens Munk lost all but three of his crew of sixty-five to scurvy in 1619, overwintering in Hudson Bay during a failed attempt to find the Northwest Passage. By the end, Munk and the few survivors were sleeping alongside the corpses of their shipmates, “for there was then nobody that could bury their bodies or throw them overboard.”

The backstory behind this gruesome means of death lies in the body’s inability to produce collagen. Vitamin C is necessary for the hydroxylation of proline and lysine, and without these collagen can no longer form. Collagen, in turn, is necessary to keep your body together, and as scurvy advances joint pain and swelling accompany wounds that do not heal or even re-open and begin to bleed again. (Trapped in the Arctic in 1832, explorer John Ross began to bleed from wounds he’d received decades earlier in the Napoleonic Wars.) Your teeth come loose from your gums, because your body literally can no longer hold itself together.

Well after De la Ascension’s voyage, scurvy continued to be little-understood—in his case, symptoms abated once the missionaries gave up and sailed for home, and while it was cactus they acquired from indigenous Mexicans that probably saved them, De la Ascension came to believe there was something poisonous in California’s air itself. Known also as mal de terre—“land disease”—all manner of hypotheses for its cause were floated. Pyrard, who thought it contagious, blamed “great length of voyage, want of cleanliness, sea air, the corruption of water and victuals,” to name a few (though to his credit he did recognize citrus fruits as an easy cure-all). Other opinions blamed excessive amounts of salted meat and fish, “which heat the blood and corrupt the internal parts.” In 1593, Sir Richard Hawkins suggested as possible cures burning tar on the deck of the ship or sprinkling it with vinegar, and to keep the crew occupied with some “bodily exercise of work, of agility, of pastimes, of dancing, of use of arms.” Hawkins, too, understood that citrus helped abate scurvy, but went on to plead for a better understanding of the disease: “I wish that some learned man would write of it, for it is the plague of the sea, and the spoil of mariners.”

Hawkins’ plea not withstanding, there was little enthusiasm for finding a cure for such an incomprehensible disease so long as it only affected a few dozen sailors in far-flung locales, far from the public eye. It wasn’t until the rise of the British Navy that serious attention turned to scurvy. As it became a global power, England found itself with a fleet of ships spread out across Europe, Asia, and the Americas, that needed to be kept at sea for months on end. What had once afflicted small ships at the ends of the mapped world was now sapping the strength of the greatest navy in the world. In the eighteenth century, scurvy was responsible for more deaths in the Navy than enemy actions: in 1780 alone, scurvy killed 1,600 men in a fleet of 12,000, while enemy action killed only sixty. Once a disease of exploration, scurvy had become a disease of empire.

In the annals of the disease, two men are mostly credited with discovering a cure: James Lind and Gilbert Blane. While citrus fruits had long been anecdotally treated as a cure, so were a whole host of other naturopathic remedies, and it fell to the young surgeon’s mate James Lind to design a now-famous test of various remedies. Lind, who enlisted at the age of twenty-three without much formal medical training, became obsessed with scurvy and its effects, and in 1747 gathered together twelve sailors with scurvy, which he ordered fed the same meals for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and then divided them into six groups, administering various known cures for scurvy to each group:

· One quart of hard cider

· Twenty-five drops of elixir vitriol

· Two spoonfuls of vinegar

· Half a pint of sea water

· Two oranges and one lemon

· A medicinal paste made up of garlic, mustard see, balsam of Peru, dried radish root and gum myrrh; along with a drink of barley-water with tamarind, and finally crème of tartar as a laxative

It took only six days for those on citrus fruits to recover, though the hard cider group also saw some limited improvements in symptoms. Those who gargled the elixir vitriol had cleaner mouths and gums, but otherwise had not improved much. Lind saw no improvement in the sea water, vinegar, or medicinal-paste-and-tamarind-water groups. He concluded: “oranges and lemons were the most effectual remedies for this distemper at sea.”

Despite this undeniable conclusion, Lind’s advice didn’t immediately take hold, and scurvy rates continued to rise in the Navy. In 1780, three-thousand cases of scurvy were reported in six months in the West Indies fleet, and Admiral George Brydges Rodney appointed his friend, Gilbert Blane, Physician to the Fleet, hoping for some kind of answer. Within a few months Blane came to the same conclusions as Lind had decades earlier: “scurvy, one of the principal diseases by which seamen are afflicted, may be infallibly prevented, or cured, by vegetables and fruits, particularly organs, lemons, or limes.” The intransigence of bureaucracy kept Blane’s recommendations from being widely implemented for another fifteen years, until in 1795 he was appointed to the Board of Sick and Wounded Sailors. Soon after, lemon juice was added as a staple to English ships, and incidences of scurvy plummeted. The British Navy had finally seen the light, and from 1796 until 1814, according to Carpenter, the British Navy distributed over 1.6 million gallons of lemon juice.

There would continue to be occasional problems through the nineteenth century. In 1819, for example, while attempting to locate the Northwest Passage, William Parry’s supply of lemon juice froze (though he’d had the foresight to bring flats of cress and mustard, which he grew in his cabin and fed to his men to stave off the worst of the disease’s effects.) But as the century progressed, the disease and its horrific effects faded from living memory. In retrospect, it seems to us (who’ve understood the mechanisms of Vitamin C for a hundred years now) all rather silly, but the cure of scurvy changed the entire life of the seas. Lind and Blane’s discoveries prevented sailors on long voyages from getting sick—in doing so they not only opened up the nineteenth century to polar exploration, they also ensured a century of European colonialism.

Back on board our ship, I had an orange in tribute to those seven unlucky volunteers of Smeerenburg, who lie, along with a hundred of their comrades just beyond the blubber ovens. Smeerenburg is littered with sailors’ graves—the remains of those who died from scurvy, from drowning, and other whaling mishaps.

Dying in Svalbard is hard—being buried is, in a way, much harder. While survivors tried to give these men a decent Christian burial, sufficient to last them until the Resurrection, burying bodies in permafrost doesn’t always work so well. Over the years, the annual freezing and thawing of the ground just below the surface has the curious effect of gradually raising up large objects to the surface—most notably, coffins and their contents. Over the course of centuries, these whalers’ bodies have slowly been raised up—not by Christ, but by ice.

This is most visible and striking at another whalers’ cemetery, in the nearby Magdalenafjord. There, a promontory juts out into the fjord, a low hill now known as Gravnesset: “Grave Point.” Over a hundred whalers have been buried there over the years, though their rest has hardly been undisturbed, and the point is now strewn with pieces of coffin and bits of bone. Off limits to tourists after years of molestation, what remains of these whalers are now the playthings of curious polar bears.

One hundred and seventy-five years earlier, another traveler to Magdalenafjord had found these graves in a similar condition. Leonie d’Aunet, known today (sadly) mostly as a one-time mistress of Victor Hugo’s, finagled her way onto a polar expedition led by Joseph Paul Gaimard and reached Gravnesset in July of 1838. (Gaimard originally asked her to invite her husband, the painter François-Auguste Biard, but D’Aunet would only extend the invitation on the condition that she herself also be allowed to join the voyage.)

Writing of the remains she found, D’Aunet described first the relics of those early whaling days: the bones left behind by Spitzbergen’s first hunters. “These great fish-bones, whitened by time and preserved by cold, seemed like the skeletons of giants, the inhabitants of the city which had just foundered close by. The long, fleshless fingers of the seals, so like those of the human hand, rendered the illusion striking, and caused feelings of terror.” But soon, however, she turned her attention to the hunters themselves:

I left this charnel-house, and, making my way over the slippery soil with precaution, I went on towards the interior. I soon found myself in the midst of a kind of cemetery; this time it was really relics of humanity that lay upon the snow….Two coffins placed in the hollow of a rock were in excellent keeping; the bodies which they enclosed had not only their flesh on, but even their clothes, but no inscription recorded either the name or the country of the dead. I counted fifty-two tombs disseminated in this cemetery, more frightful than any other, without epitaphs, without monuments, without flowers, without reminiscences, without tears, without regrets, without prayers; most desolate cemetery, where it seems as if forgetfulness twice enshrouds the dead, where a sigh, or a voice, or even a footfall is never heard; most fearful solitude; deep, icy silence, only broken by the howl of the white bear or the roaring of the tempest!

In the almost two-hundred years since D’Aunet picked her way through those forlorn bones, the only changes have come from human hands: tourists who’ve taken bones for themselves, and a government fence to keep them out. The arctic itself, largely devoid of moisture and bacteria, preserves its kills well—an ever-lasting monument to human aspiration and folly.

We turned our backs on the scurvy-ridden bones of sailors long dead, and continued sailing north.