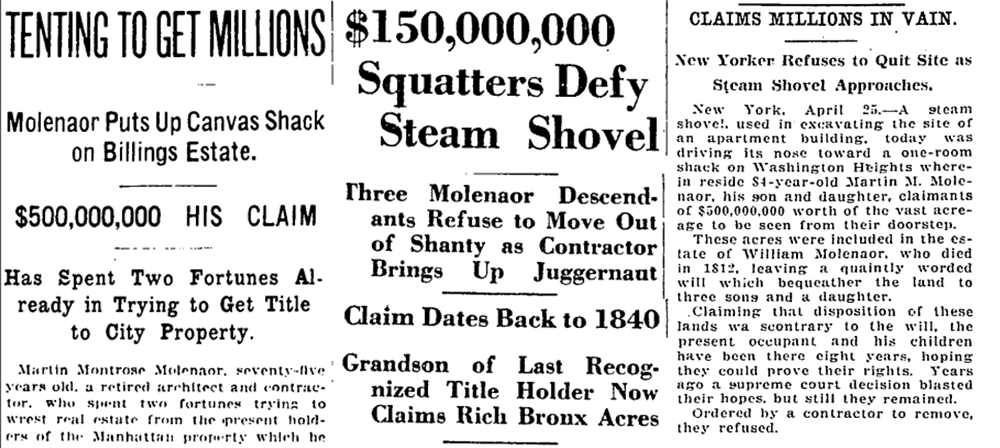

Tryon Hall, C.K.G. Billings’ estate, Washington Heights, New York City, c. 1916. Library of Congress, Bain Collection.

In the spring of 1913 a seventy-five-year-old gent with a chip on his shoulder took up residence in a thirteen-by-twelve-foot squatter’s shack on the opposite side of Broadway from gas tycoon C.K.G. Billings’ palatial château atop Fort Tryon Hill and loudly proclaimed that he owned seventeen acres of the Billings estate, plus seven acres on the east side of the street, including the land beneath the shack, and forty-seven acres between 120th and 129th Streets spanning from Harlem to Manhattanville—all told, some seventy-one acres of prime Manhattan real estate. He figured the value of the three parcels at somewhere between $300 million and $500 million.

The shack had low ceilings, a wooden floor and sides, and a canvas roof. It was equipped with a stove, chairs, table, and bunk. A smoky kerosene lamp provided light; neighbors let him draw water from their taps. “I expect to stay here quite some time,” the man announced.

Martin Montrose Molenaor’s quixotic campaign to reclaim much of upper Manhattan as his own had begun thirty-five years earlier, when on January 30, 1878, he served notices to some two hundred tenants of houses, stores, and churches occupying buildings in the three parcels in question, demanding that they either pay him rent or vacate the premises.

“You are hereby notified that the heirs of David W. Molenaor are the owners of the premises now occupied by you,” the notice read, “and that you are required to pay the rent of the said premises to the undersigned, or, in default thereof, to surrender the same to him. Martin M. Molenaor.”

A Catholic priest who received Molenaor’s notice tore it up. But Molenaor was just getting started. A few days later, he made the rounds again, this time painstakingly gluing large for sale signs on all the buildings. Enraged occupants just as quickly removed them. “I was not long in getting that notice off my building,” William H. Higgins, owner of a hotel at the corner of Eighth Avenue and 125th Street, said, “although it had been stuck very fast with good paste.”

In pressing his claim, Molenaor was taking on a group of extremely wealthy, influential landowners, which included not only Billings and Higgins but also Vincent Astor, James Gordon Bennett, and the Mutual Insurance Company. Observers didn’t give him much of a chance.

“The Molenaors are poor,” one resident said, “and a lack of funds to carry on actions at law will be a disadvantage to them; while on the occupants’ side there is plenty of money to employ capable lawyers.”

Sure enough, Molenaor’s adversaries sent what he later recalled as “an army of lawyers” after him, and by 1882 he was bankrupt. He moved to Colorado and took up ranching, then went to Flagstaff, Arizona, where he worked as an architect and builder. By 1913 he and wife Evalina had saved enough money to return east and resume the fight. In New York, Molenaor founded the Molenaor Recovery Company, with an office at 50 Church Street, and he and Evalina, along with son Wilfred, thirty-eight, and daughter Evalina, or Evelyn, forty, moved into the shack below the Billings estate. Evelyn, a nurse, became the family’s breadwinner, while Wilfred, a carpenter, assisted his father by reading up on property law.

Martin M. Molenaor was born in 1838 in his grandfather’s homestead at Eighth Avenue and 125th Street. During the Civil War he moved to the Bahamas, where he married Evalina and where their first two children, Montrose and Evelyn, were born. Then the family moved to St. Augustine, Florida, and had three more children, including Wilfred, born in 1871.

In 1872 Molenaor’s brother Andrew visited him in Florida and told him their grandfather’s will had been discovered in a “secret drawer.” In 1878 Molenaor returned to New York with Evalina and the five children, opened a jewelry business on Fulton Street in Brooklyn, and laid plans for the reclamation of his grandfather’s land.

The grandfather, William M. Molenaor, had died in 1812 and his estate, including his land, “good horse and chaise,” “black girl Sarah,” and “black boy Isaac,” was divided between his wife Mercy, a daughter, and three sons. The oldest son was David William Molenaor, Martin’s father, who in the 1820s invested heavily in the Harlem Canal Company. His land had been put up as security to cover the canal company’s debts, and when the company failed much of David’s considerable inheritance disappeared. By 1850 David had lost everything, his occupation on that year’s federal census listed as “None.” (Under “Real Estate” the census enumerator had simply entered a question mark.) He died in 1858.

The gist of Martin M. Molenaor’s claim hinged on the wording of a single clause in his grandfather’s will: “To my eldest son, David William Molenaor, the legitimate heirs of his body or the nearest heirs of his body, I do give and bequeath all my homestead…”

Molenaor interpreted that line as meaning that his grandfather had intended to pass on his estate not only to his son but also to his son’s children and their children, the “heirs” of David’s “body.” To Molenaor’s way of thinking, that meant that his father had been granted only a “life interest” in the land, not a clear title, and therefore had had no legal right to sell it. And if he had had no right to sell it, Molenaor figured, then all of his father’s transactions and all subsequent transactions pertaining to the land in question were invalid, and the land must still belong to the rightful heir—none other than Martin Montrose Molenaor.

In 1916 the Kiowa Realty Company and its president, Emil Fried, owner of five vacant lots at the southeast corner of Broadway and Hillside Avenue, where Molenaor was squatting, sued for eviction. This was precisely what Molenaor wanted—a day in court. Kiowa Realty Company v. Martin M. Molenaor et al. became a test case that was watched carefully by many landowners in Washington Heights, Harlem, and Manhattanville who wished that Molenaor would go away, since his endless claims against their property were beginning to muck up the clear transfer of titles.

The case went all the way to New York State’s Supreme Court, First Judicial District. “[The defendants], as I understand it, do not contest the general proposition of law,” Justice Nathan Bijur wrote, “but hold it inapplicable because, as they construe the will, no estate was devised to David William Molenaor, but…only ‘to the legitimate heirs of his body, etc.’ From the standpoint of grammar, they urge that the language should be construed as in the phrase ‘John Jones, his mark,’ and that the devise [the land] should be read as one to the legitimate heirs of the body of David William Molenaor.”

“To this extraordinary construction I cannot give my assent,” Bijur continued, slamming the door shut once and for all. “Altogether, apart from the violence which I think it does to the rule of grammatical construction prevalent at the time of execution and probate of this will, the last will itself is replete with persuasive suggestions of the meaning of the testator to the contrary.”

Bijur then dutifully cited dozens of precedents to back up his opinion that in 1812 William M. Molenaor surely had meant to give his property to his son David William Molenaor, come what may; that the son, as owner, had been entitled to sell it; and that, therefore, Martin M. Molenaor had no claim to the land beneath his shack, nor to the Billings estate across the street or the lots in Harlem and Manhattanville. Bijur ruled in favor of Kiowa Realty.

That should have been the final blow, but still Molenaor held out, his shack sitting undisturbed on its vacant lot.

In the spring of 1921 Molenaor was eighty-four and nearly blind. William F. Norton, a contractor and the new owner of the lot upon which the Molenaors squatted, appeared at the shack’s door and told the family to clear out; he wanted to put up a commercial building on the lot. The Molenaors refused to budge. Norton began excavating anyway, each day coming closer to the shack and each day making the Molenaors angrier and more determined to stay.

“Undermine our home, will you?” Evelyn shouted at the steam shovel operator. “Still, we can only die once and we might as well die defending our home.”

Norton stopped digging just short of the shack, spooked by the possibility that he might injure, or even kill, the Molenaors, who crowed that he had been bluffing all along. But the stress of being threatened with a steam shovel had been too much for Molenaor, Evelyn told New York Herald reporter Eleanor Booth Simmons. He died shortly afterward.

Simmons had visited the shack before, and had glimpsed Molenaor gazing longingly through the shack’s small windows at the Billings estate, which John D. Rockefeller had acquired in 1917. “All that…is mine,” he told her. “Some day the courts will decide that it is mine, and I shall be one of the richest men in America, richer than Rockefeller, who fancies that he owns that Washington Heights property.”

Adapted from Broadway: A History of New York City in Thirteen Miles by Fran Leadon. Copyright © 2018 by Fran Leadon. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.