Portrait of Three Women, late nineteenth century. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Near the end of his best-selling biography of Queen Victoria, Lytton Strachey delivers a sketch of her notoriously chilling response to social blunders, should one be committed in her midst:

The royal lips sank down at the corners, the royal eyes stared in astonished protrusion, and in fact the royal countenance became inauspicious in the highest degree. The transgressor shuddered into silence, while the awful “We are not amused” annihilated the dinner table…The Queen would observe that the person in question was, she very much feared, “not discreet”: it was a verdict from which there was no appeal.

This mortal social wound—being branded as indiscreet by Her Majesty—implies the value she placed upon its opposing quality, discretion. Or perhaps it merely indicates that commoners were denied the privilege of feeling at ease in her royal presence; as such, telling the wrong cheeky joke was a sign of grave presumption. Discretion was a crucial attribute, its lack a gaping, irreconcilable absence likely to result in one’s exclusion from future palace dinner parties.

Queen Victoria died two decades before the publication of Strachey’s 1921 biography, titled, simply, Queen Victoria. This timing was certainly to everyone’s benefit. Queen Victoria was a clamorous departure from the previous era’s biographical conventions, of which pointed and assiduous discretion was one. So, too, was Queen Victoria’s more famous predecessor, Strachey’s 1918 Eminent Victorians. Its short biographies of Cardinal Henry Manning, Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold, and General Charles Gordon—figures representing dominant Victorian ideologies—were intended to lay bare the subjects’ folly and foulness with humor that, Strachey supposed, “might be entertaining, if it was properly pulled off.”

Strachey, like his Bloomsbury Group friends and interlocutors, regarded discretion as a creative impediment. Roundly objecting to it on aesthetic principles, he argued, according to his own biographer, Michael Holroyd, that it was “not the better part of biography.” For one thing, it limited the writer’s purview: despite the characteristically bulky word count of Victorian biographies (the length of Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton but without the notes), their “scrupulous narration” was, in Strachey’s estimation, dehydrated of any “unexpected” and illuminating details or “obscure recesses, hitherto undivined.” A biographer’s subject is often already deceased; dry prose need not exacerbate the matter. Even in this essay’s opening passage, the reader catches flickers of Strachey’s delight in human farce, his well-whetted capacity for uncovering drollery in mundane contexts. In his hands, Queen Victoria’s face transforms into hyperbole, as if witched into the stuff of cartoon animation. Far from a depiction of magisterial solemnity, the drooping sides of her mouth and the “protrusion” of her “royal eyes” seem better suited to a description of Elmer Fudd learning that rabbit-hunting season has been canceled.

It is due to Strachey’s literary influence that this image of Queen Victoria, bug-eyed and scowling over her supper, no longer strikes readers of biography as a revolutionary rhetorical pose. It is now commonplace for biographers to expose their subjects as occasionally silly or ridiculous—not necessarily to lampoon them as Strachey-esque oddballs, but to disclose petty or self-serious or pigheaded foibles and to treat them as inherent to personhood. Therein rests an implicit understanding: historical figures are neither saints nor archetypes, and narratives of their lives are not morally instructive simply by virtue of their eminence. A human life will always exist in excess of any theme, any organizing principle. Too many flicks of discretion’s paring knife, and it might not resemble life at all.

But as Strachey whittled his Victorian subjects’ lives into literary form, his object was not simulacrum—he had no taste for biography’s scarecrows, stuffed and cinched with the minutiae of dates, events, and familial lineage—nor did he condemn his subjects to overstated caricature. One might argue that either mode would have imbued Queen Victoria and the eminent Victorians with more structural importance than Strachey cared to bestow. For though a monarch, Manning, Nightingale, Arnold, and Gordon are his subjects, their lives are not the literary frames upon which his works rely for coherence. It is instead Strachey’s subjectivity that scaffolds both Eminent Victorians and Queen Victoria. Each of his subjects emerges in the text as an amalgam of fact, editorial, and speculation, vivified in accordance with Strachey’s impressions, his politics, or his creative instincts.

One might protest that such an effect is, to some extent, inevitable. Like any set of words committed to the page, a biography will harbor an authorial angle. The most assiduous and diligent exertions toward objectivity cannot amend the slant begat by one’s basic and automatic preferences. But for Strachey, to tell it slant was the point. Qualities strenuously avoided by so many present-day biographers—partisanship, an intently crafted narratorial voice that governs the reader’s view of the subject—he treated as virtues. They were also crucial tools for elevating the historical record to the stratosphere of art. His subjects were also his creations, their enclosing narratives the meticulously crafted vehicles that achieved particular literary ends.

For Strachey, there was no other way. As he advises in his preface to Eminent Victorians, this methodology is not mere preference; rather, it is best biographical practice. If the biographer is wise, he writes, “he will row out over that great ocean of material, and lower down into it, here and there, a little bucket, which will bring up to the light of day some characteristic specimen…to be examined with a careful curiosity.” Eminent Victorians’ first micro-biography, on Cardinal Manning, traces the ecclesiastic’s obsessive ambition; Queen Victoria is preoccupied with its subject’s irrepressible, grandiose desire for her husband. It is not enough to chronicle a life, Strachey implies; one must curate it, like a gallerist of personal history strategically searching for a subject’s most dramatic qualities and quirks. He executed a vision of Victorian history that only he could render.

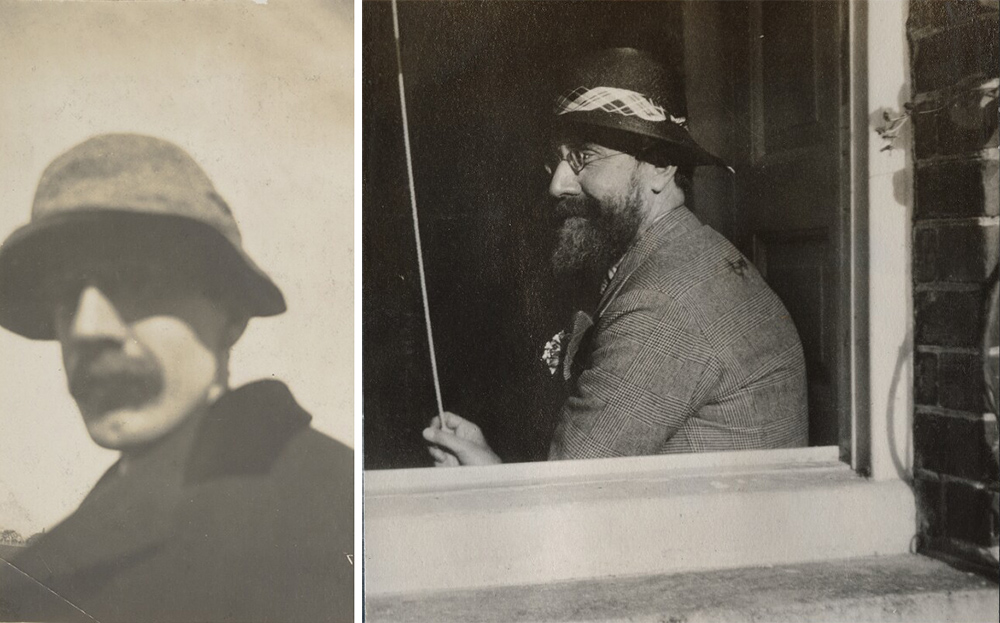

According to the conventional markers, Giles Lytton Strachey lived the first two decades of his life in the Victorian era. Born in London on March 1, 1880, he was approaching his twenty-first birthday when Queen Victoria died in January 1901. He demonstrated precocious literary and scholarly promise, distinguishing himself among his gaggle of siblings despite the debility of frequent illness. His frailty endured through adulthood, ebbing and flowing in its intensity.

Strachey pursued the usual education for a person of his background, first at boarding schools and then at Trinity College, Cambridge. He performed well as a university student, winning the Chancellor’s Gold Medal for poetry in 1902. But Strachey’s academic successes do not fully reflect the prodigious influence of the intellectual community he found at Trinity College and that he would maintain throughout the rest of his life in the form of the Bloomsbury Group. Here he befriended Clive Bell, Leonard Woolf, Thoby Stephen, and Stephen’s sisters, Vanessa and Virginia (later, Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf). He met the analytic philosopher G.E. Moore, whose 1903 work Principia Ethica shaped the philosophies of the Bloomsbury Group; Moore’s arguments for the broadening impacts of works of art upon human consciousness helped mold Strachey’s own theory of aesthetics.

After graduating from Cambridge, Strachey refined his positions on art and literature as a critic for The Spectator, and in 1912 he published the well-reviewed but largely ignored Landmarks in French Literature. Six years later, he had better luck when Eminent Victorians became a rollicking success. Queen Victoria, also popular, followed in 1921. His last book, a Freudian biography of Queen Elizabeth I, Elizabeth and Essex: A Tragic History, came out in 1928. Strachey succumbed to stomach cancer four years later, purportedly uttering at the last, “If this is dying, then I don’t think much of it.” If this is true, then it was, at least, an on-brand departure from life: the Victorians’ most devoted critic could not abide the pious solemnity of a Dickensian deathbed scene.

He had waded through enough of those sober tableaux to know what to avoid emulating. Strachey’s bibliographies largely comprise conventional, two-volume biographies: in addition to offering exhaustive chronologies of his subjects’ lives that he could mine for content, they must have been replete with stylistic gestures that inspired his oppositional approach. Surely, too, their tendency toward blatant hagiography solidified Strachey’s resolve to depict people as they had lived, not as they were idealized—in other words, to practice the art of biography. Indeed, one could make the case that his source material achieved markedly different ends. Events in the Life of Charles George Gordon, the 1886 biography by Gordon’s brother, Henry William Gordon, begins with a verse from Philippians in order to convey the “strong resemblance in the lives of [Jesus and General Gordon]; while both suffered death sooner than surrender their faith as Christians.” (While Strachey also considers Gordon’s relationship to his faith in Eminent Victorians, the volatile, pig-headed Gordon is decidedly not posited as a Christ-like figure.) Edward Cook’s 1913 The Life of Florence Nightingale claims to reveal the woman behind the legend—and asserts that “the real Florence Nightingale was…greater. Her life was built on larger lines, her work had more importance, than belong to the legend.” Perhaps, as far as Cook, Gordon, and other like-minded chroniclers were concerned, producing anything less than elephantine blocks of minute biographical detail would be tantamount to disrespect.

Strachey did harbor a few romantic ideas of biography, all of which were woefully unrealized in his contemporaries’ work in the genre. Eminent Victorians’ preface serves as his manifesto, in which he assesses the dismal state of British life-writing and what its revitalization demands. “The art of biography seems to have fallen on evil times in England,” he writes. “Those two fat volumes…who does not know them, with their ill-digested masses of material, their slipshod style, their tone of tedious panegyric, their lamentable lack of selection, of detachment, of design?” The Victorian biography might have triumphed in the realm of discretion, but it bungled at the level of craft.

A writer’s priorities, and their perception of a text’s function, influences its form. Strachey’s object was to create a singular work of literature. The biographers he denounces in his preface likely regarded their own task quite differently. Victorian biographies were projects typically undertaken by the subjects’ relations or one of their acolytes—another form of partisanship, albeit quite different from Strachey’s own. They would, moreover, rely on the subjects’ families for access to all the necessary primary materials: diaries, correspondence, anything else that was crucial to understanding the breadth and nuance of their lives. That reliance could result in deference.

The Victorians’ concerns with the robustness of their collective British identity surely amplified this solicitude. It was during this period that Great Britain fomented its imperial interests and thrust itself across the globe, seizing territory that further enlarged and enriched its swelling empire. Britons sought a coherent national narrative to distinguish the country from its rivals and ensure its reputation as an omnipotent force. But while Strachey might scoff at the suggestion, biographer Hermione Lee does not dispense wholesale with the aesthetic value of Victorian biographies. They could, she maintains in Biography: A Very Short Introduction, be “eloquent and vivid,” although “mainstream” exercises in the genre were “stolid,” with “heroic lives” tendered as patriotic “expressions of imperial confidence and assertiveness.” If one were forced to choose between the two, compelling propaganda was of more civic use than refined literary art.

Victorian readers thus turned to the page harboring at once nationalistic interests and their own artistic predilections. In 1881 historian John Anthony Froude published Reminiscences, diaries and correspondence maintained by the late Jane Welsh Carlyle that cumulatively relates the depths of Carlyle’s domestic misery in her marriage to Froude’s recently deceased mentor, the widely esteemed Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle. Carlyle had entrusted these papers to Froude years before his death, and Froude, for his part, harbored no Strachey-esque urges to defame or expose. As Lee explains in her recounting of the history, it was quite the contrary: Froude wanted only to exhibit the same intellectual honesty he had admired in Carlyle. He later published a conventionally deferential biography of his friend, the first volume in 1882 and the second in 1884. (Perhaps, in part, that panegyric served as a mitigation measure in the wake of less glorifying revelations. In 1883 Froude also published Letters and Memorials of Jane Welsh Carlyle, shedding further light on the couple’s unhappy union.)

The public erupted in choler. For airing Jane Welsh Carlyle’s papers, Froude was no better than a libelous Brutus; before long, the term Froudacity was wielded as a synonym for “treachery, immorality, inaccuracy.” But in spite of this moral frenzy, Froude had withheld the most sensitive—and possibly to some, the most emasculating—personal detail about Thomas Carlyle, his sexual impotence. When Froude’s family posthumously published his memoir, My Relations with Carlyle, in 1903, readers learned that this condition had been an acute contributor to the Carlyles’ marital strife. They were, again, furiously indignant on Thomas Carlyle’s behalf. To say nothing of basic indiscretion, broadcasting this specific vulnerability, particularly for a British intellectual titan like Carlyle, did not exactly augment the nation’s campaign to promote itself as a militant penetrator of foreign lands.

Toward the end of his career, Strachey himself would publish an essay on Froude and the vitriol incurred by his “gospel” of Thomas Carlyle. As far as Strachey is concerned, Froude’s contributions to his friend’s legacy merely indicate that his “adoration was of so complete a kind that it shrank with horror from the notion of omitting a single wart from the portrait.” “The Victorian public,” meanwhile, was “unable to understand a form of hero worship which laid bare the faults of the hero”—even as it feasted “upon the unexpected banquet to its heart’s content.” The thrill of scandal is rarely incompatible with moral affront or the performance of it. This was a lesson Strachey took to heart in his own approach to biography.

Queen Victoria nurtures readerly desires for intimacy both through its literary style and its narratorial intrusions. It is written, Holroyd observes, like “a romantic novel,” and Strachey makes occasional self-referential entrances onto the page. Upon arriving at Prince Albert’s death, the great psychic trauma of Queen Victoria’s life and certainly one of its most critically defining moments, “her biographer” breaks in to reflect on the enormity of the event:

She herself felt that her true life had ceased with her husband’s, and that the remainder of her days upon earth was…an epilogue to a drama that was done. Nor is it possible that her biographer should escape a similar impression. For him, too, there is a darkness over the latter half of that long career.

Fewer than seventy pages follow, covering nearly four decades of Victoria’s life (over twice as many pages precede them). If Strachey lacked the primary documents to flesh out the details, as he insists, this novelistic flourish makes the conciseness seem almost intentional. “With Albert’s death a veil descends. Only occasionally, at fitful and disconnected intervals, does it lift for a moment or two…the rest is all conjecture and ambiguity,” writes Strachey. “We must be content in our ignorance with a brief and summary relation.” It’s an assertive delivery, with biographer and reader conspiratorially yoked through a strategic use of we: a paucity of information becomes the opportunity for solidarity forged between the page and the hand that turns it.

The tone of Queen Victoria runs the gamut. Strachey’s narrator is sometimes arch and sometimes tender—even, it must be said, a bit maudlin. Occasionally, whiffs of banal sexism add an infantilizing air, especially when the topic at hand is the queen’s mental acuity. Among the monarch’s other frailties, her inability to “distinguish at all clearly between the trivial and the essential” is noted. He lapses into the occasional unfortunate metaphor, as when querying whether Lord Melbourne, the first prime minister of Queen Victoria’s reign, would “possess the magic bridle which would curb that fiery steed?”

That vague, sentence-level eroticism is not coincidence. Strachey’s prose, as various critics have observed, carries recurrent reminders of human desire. Influenced by what was then cutting-edge psychoanalytic work from Sigmund Freud, a Strachey biography endeavors to depict the conflicted murk of a subject’s interiority. In the case of Queen Victoria, foregrounding as it does the queen’s marriage to Prince Albert, Strachey courts censure from more punctilious quarters by drawing the reader’s attention to the royal sex life, specifically Victoria’s enjoyment of it and—according to the biography’s thesis—Albert’s indifference to physical intimacy due to “a marked distaste for the opposite sex.” Victoria’s attraction to her husband is no historical secret, and in Strachey’s biography she appears positively besotted, even voracious, while Albert, despite his tender admiration, “was not in love with her” at the time of their betrothment and, once married, was “not so happy” as his wife. More than presenting mere insinuations, Strachey renders an erotically lopsided marriage, implying, with relative indiscretion, that Albert’s orientation made it impossible to be otherwise.

As Holroyd explains in his 1967 biography, Strachey’s emphasis upon both the prince’s disinterest in women and the emotional isolation he experienced as a foreigner living in England gestures to an interpretation of Albert as a queer man confined to a performance of hypervisible Anglo heterosexuality. “Strachey sees in Albert something of his own loneliness,” Holroyd writes, suggesting that neither prince nor biographer found full and genuine sustenance in his connections. It is no rare occurrence for a writer to recognize themselves in, or perhaps even to project themselves onto, a subject. Objectivity, however desired, is an ever-fleeing target. But Strachey isn’t chasing it in the first place—on the contrary, he draws closer, breathes down his subjects’ necks, until his own interiority is enmeshed with the inner lives he has built and bestowed upon them. This peculiar intimacy, in which author and subject are bound by the former’s affectionless fascination, fosters the conditions for an idiosyncratic authorial empathy extended amid the lacerations.

If Strachey did find himself—perhaps even inscribe himself—in Prince Albert, then one might read that cultivated affinity as its own form of discretion, carefully attired and legible only to those who knew him. He was an adolescent when, in 1895, Oscar Wilde was forced upon the stand and ultimately convicted of gross indecency for his relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas. But even as Strachey passed into adulthood, British law still criminalized consensual sexual intimacy between two men. If one was found to be a “sodomite,” whether through happenstance or blackmail, the punishment was two years’ imprisonment with hard labor, the very sentence Wilde served. It was not until 1967, the same year Holroyd’s biography of Strachey was first published, that Parliament passed the Sexual Offences Act, legalizing “homosexual acts between two consenting adults over the age of twenty-one” in the UK. This legislation, codifying a right denied to Strachey, punctuates the cultural berth separating him from Holroyd, as well as the discursive freedom available to each of them as they analyzed their subjects’ sexual dispositions. In telling Strachey’s tale, Holroyd could write with a frankness that his subject dared not risk.

Indiscretion, like any quality, cannot be conceived on a binary. As a gay writer in early twentieth-century England, Strachey could not explicitly write about queer desire; he could only insinuate its presence in his subjects, and only so long as he exercised scrupulous delicacy. His own queerness perhaps endowed him with a double vision, suggesting unspoken possibilities or perceiving undercurrents in lives that were even more constrained than his own. Yet if Strachey hoped to avoid Wilde’s punishing fate, he was limited to uncovering sites of resonance in the lives of others. Discretion might not have been the better part of biography, but it was, nonetheless, a tool of self-preservation.

Eminent Victorians and Queen Victoria were, initially, boons to Strachey’s reputation. Each garnered vigorous critical acclaim and—realizing every writer’s fever dream—their commercial success furnished Strachey with financial independence. “The reviewers are so extraordinarily gushing that I think something must be wrong,” he told his friend Ottoline Morrell in a 1918 letter about the reception of Eminent Victorians. To Mary Hutchinson, he wrote, “I’m really rather disappointed that none of the Old Guard should have raised a protest…Is it possible that the poor dear creatures haven’t a single kick left?” More than one hundred years later, scholars like Lara Kriegel identify Eminent Victorians as an “unintended…landmark text in Victorian studies.” But, perhaps to Strachey’s relief, that century-long legacy has been fraught with censure. Rudyard Kipling remarked that the book “seems to me downright wicked in its heart.” Tory politician Duff Cooper wrote in a letter, “You can feel reading the book that he is pleased that Miss Nightingale grew fat and that her brain softened.” But vastly more detrimental than speculations about Strachey’s wickedness were historians’ accusations that his text contained a host of inaccuracies. Holroyd writes that Strachey “is certainly cavalier with his sources,” sometimes allowing literary predilections to mutate fact. Strachey himself admitted to embellishing the rivalry between Cardinal Manning and Cardinal Newman, Manning’s fellow Oxford theologian. Keen to render Manning as a grim adversary, he exaggerates the contrast between the men’s dispositions, depicting Newman as the gentle, prey-like “dove” to Manning’s “eagle.” “I think perhaps my whole treatment of Newman is over-sentimentalized,” Strachey wrote in a June 1918 letter, “to make a foil for the other cardinal.” In other instances, Strachey relied upon sources that are themselves incorrect and whose errors were uncovered only after his death. And he was criticized for inspiring a host of pale imitations, like Harold Nicolson’s Tennyson and Hugh Kingsmill’s Matthew Arnold, biographical projects that endeavor to lambast their subjects but lack the singular skill of Eminent Victorians’ construction. It is rather an unfair charge to lay at Strachey’s feet but was lobbed at him nonetheless.

Queen Victoria did not galvanize the same controversy as Eminent Victorians, but like its predecessor, its publication was met with sensational excitement. The first five thousand copies printed in Great Britain sold out in twenty-four hours, and four more printings were required that year. (By comparison, Emily Crawford’s 1902 biography Victoria, Queen and Ruler, called “interesting” and “gossipy” in a September 12, 1903, edition of the Brisbane periodical The Queenslander and cited by Strachey in his bibliography, seems to have made a quieter impression.) Americans were even more enthusiastic, leading to seventeen printings of the U.S. edition over the course of the 1920s. In one corner of Bloomsbury, the response to Queen Victoria wavered in ambivalence. Virginia Woolf, to whom the book is dedicated, found the book “flimsy” and was envious of its triumphant performance. In spite of her fraught reaction, she anticipated that it would wield great influence. “In time to come Lytton Strachey’s queen Victoria will be Queen Victoria,” Woolf writes, “just as Boswell’s Johnson is now Dr. Johnson. The other versions will fade and disappear. It was a prodigious feat.”

But as it stands, Woolf’s prediction overestimates the longevity of her friend’s work. Today Strachey’s Queen Victoria is little discussed, with no recent editions, although the shadow of its influence endures in inviting writers to highlight, however softly or harshly, their subjects’ shortcomings and eccentricities. Eminent Victorians is more readily available and is unquestionably the work for which Strachey is best known. Still, it may be that the book’s title, divorced from its contents, has survived most durably over the past 104 years. Its 2018 centennial passed with meager fanfare beyond academia’s walls.

Many of today’s popular biographies bear greater resemblance to the two-volume Victorian behemoths than to Strachey’s hyperstylized, whittled-down experiments, perhaps mostly in terms of their mass and breadth. (One recent notable exception among many over the past century is Alexis Coe’s best-selling You Never Forget Your First, an irreverent biography of George Washington.) Strachey emboldened his fellow life-writers to take a chisel to their subjects’ pedestals, and contemporary authors heed that call in varied ways. Some may develop a hostile attitude toward their subject, as Patrick French did in the course of writing his biography of V.S. Naipaul, The World Is What It Is, published in 2008. Others may take on a historical figure so abhorrent that rehabilitation, to say nothing of hagiography, would be a moral impossibility (think, for example, of the many books written about Adolf Hitler). Whatever the case, the reader is supplied with such an abundance of biographical detail that presumably they can come to their own conclusions. Casting aside Strachey’s “little bucket,” many biographers opt instead for the “great ocean of material” their forebear spurned as extraneous. Is this plenitude a response to readerly inclination? In her 1995 book The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, Janet Malcolm excoriates the “fundamental and incorrigible nosiness”—humanity’s basic indiscretion, one might say—that, in her assessment, engines both biographical writing and readers’ taste for it. “We have very low natures,” remarked Hermione Lee during a January 2022 interview on The Biblio File podcast, “but those low natures are mixed with more valuable things like admiration and wonder, and I think it’s very hard to sort out where one stops and the other begins.” With such inextricably alloyed motivations, readers might approach satisfaction only when they feel privy to everything knowable about a person. In this way, reading biography may coddle the illusion that we are assessing the subject fully and fairly, according to our own terms.

Meanwhile, Strachey delivers the Victorians on his undeniable terms, with a saucy yet elegant humor that distinguishes him not merely as a biographer but as a devilishly delightful prose stylist. Eminent Victorians is often quite a funny book. Strachey’s subjects pay the price for the readers’ good time, with each ousted from the altars so diligently tended by their Victorian acolytes. The authorial voice seems to share genetic material with the gleefully bitchy narrator of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair—void of any softening sympathies, both observe their characters with amused detachment and often bitter contempt. Of Nightingale, Strachey writes, “A Demon possessed her. Now demons, whatever else they may be, are full of interest. And so it happens that in the real Miss Nightingale there was more that was interesting than in the legendary one; there was also less that was agreeable.” Cardinal Manning, we are made to understand, “ruled his diocese with the despotic zeal of a born administrator,” in what might be the book’s most consummate evisceration, save for Strachey’s assertion that Nightingale, demanding brutish and unceasing bouts of administrative labor from her disciples, worked British statesman Sidney Herbert to an untimely death.

And yet, to my mind, Strachey’s most striking literary gesture is not the annihilating zing of his humor but the subtler, more insinuating performance of free indirect discourse. He frequently yet fleetingly assumes the perspective of his subject—for instance, widowed Queen Victoria, who “felt that her true life had ceased”—or even an ancillary figure: Prince Albert bemoaning his loneliness at court or Nightingale’s mother wondering at the singularity of her daughter’s aspirations. Amid a depiction of Manning’s anguished but unremitting ambition, the author suddenly seems to don a mask bearing the face of his subject: “He vowed to Heaven that he would seek nothing—no, not by the lifting of a finger or the speaking of a word. But, if something came to him—? He had vowed not to seek; he had not vowed not to take. Might it not be his plain duty to take? Might it not be the will of God?” Manning, as performed by Strachey’s narrator, appears as a slick bargainer, reassuring himself that rank ambition will not jeopardize his salvation. It’s unlikely that Manning uttered these words, cynically devised as they are, but they achieve the effect Strachey wants: one more Victorian hypocrite is toppled from his pillar.

In the genre of biography, the use of free indirect discourse might be seen as presumptuous. It is certainly a form of literary license, one more likely to deliver in works expected to carry literary value (Strachey, of course, intended for both Eminent Victorians and Queen Victoria to be received as literature). The question is to what extent one expects this quality from biography or whether one even should. During her Biblio File interview, Lee—claiming no airs—remarks that biography is not “a top-level creative art,” but rather a form reliant upon others’ “creative genius.” Perhaps this position informs the method of her craft, for free indirect discourse relies on a trope she admonishes against: the imposition of a biographer’s assumptions upon a subject, with liberties such as “It must have been, or she might have felt or he must have thought.” But then again, Eminent Victorians, as well as Queen Victoria, shirk a key premise that Lee and arguably most contemporary biographers accept: that biographies should be rigorously based in fact. Strachey was not deliberately inaccurate; nevertheless, he portrayed his subjects with dramatic latitude. He might beg to differ with Lee’s assessment of their shared genre. When Strachey contends that discretion hinders the art of biography, he implies that the value of its converse lies not only in the liberty of casting witty aspersions or making sly references to Dr. Arnold’s sexual productivity. (The Victorian educator had ten children, and six of them were born in the span of eight years.) For Strachey, indiscretion serves as a more capacious literary philosophy, through which biography becomes a mélange of fiction and fact. Like Wilde’s critic-artist, for whom “the work of art is simply a suggestion for a new work of his own,” Strachey practiced an art of indiscreet biography that treats the subject—who, unlike a work of art, can never be altogether known in the first place—as a source for personal artistic inspiration.

How, then, can one call these works biographies? Perhaps one doesn’t. Scholar Todd Avery has made the argument that Strachey’s oeuvre—his Victorian biographies and his 1928 Elizabethan biography, Elizabeth and Essex—anticipates the cross-pollinated genre of “biofiction,” in which a historical figure’s life is fictionalized. Avery emphasizes that Strachey is as dedicated to self-expression and “self-analysis” as he is to shaping the life of his biographical subject, a purpose he doesn’t bother concealing from the reader.

This may be Strachey’s ultimate bibliographic indiscretion: the audacity to put himself first, to dare to suggest that one is always writing about oneself. And if this is the case, why be shy? As B.D. McClay writes for Gawker, “At some point in life, we come to realize we exist in a context.” Strachey knew his context, and he also knew that despite Woolf’s auguring, his would not be the last words on Queen Victoria or his quartet of eminent Victorians. Others have had their say in the intervening century; more will continue to do so. Strachey’s brilliance—his finicky, searing, bitchy brilliance—supersedes the genre he inhabits, because, rather than attempt to be the definitive biographer on his subjects, he aspires instead to be an artist. Creep not along the margins or within the parentheticals: it’s a primary structuring principle of Strachey’s work, and it prompts a reconsideration of one of his most famous declarations, which, like so many others, is from the preface of Eminent Victorians. “Human beings are too important to be treated as mere symptoms of the past,” he writes, for “they have a value which is independent of any temporal processes—which is eternal, and must be felt for its own sake.” Lytton Strachey knows we must remember the Victorians, believes that even in their rank, rampant hypocrisy—and despite the inescapable frame of context—they deserve a readerly gaze undistracted by the pell-mell of history. And in the project and craft of memorializing, he gallantly asks us to remember him as well.