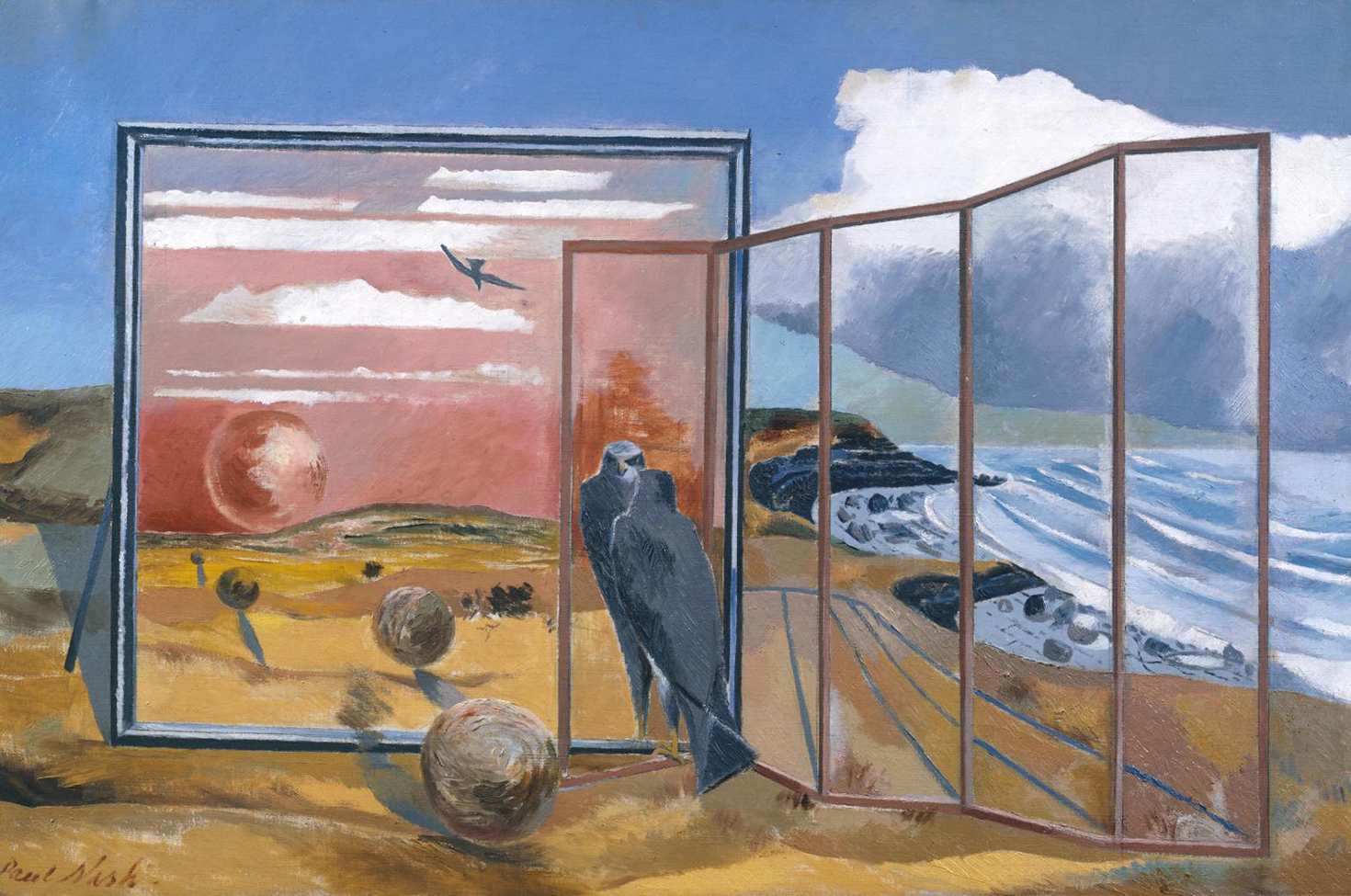

Landscape from a Dream, by Paul Nash, c. 1936. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

It was no coincidence that the world’s introduction to industrialized warfare determined the shape of Johan Varendonck’s opus on daydreams. Varendonck himself didn’t expect daydreaming to be the subject of his only book; his studies began in a different field. But World War I—and Freud—intervened.

Born in 1879 to a Belgian schoolteacher and his wife, Varendonck hadn’t done much to distinguish himself by the time he turned thirty-five. Following in his father’s footsteps, he took up a career in education, becoming a lecturer at Ghent University, just eleven miles from his hometown of Zelzate. He eventually enrolled in a pedagogical doctoral program in Brussels, but the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s declaration of war on July 28, 1914, interrupted his graduate studies and pursuit of a better life.

Academic ambitions notwithstanding, Varendonck volunteered for armed service the moment Kaiser Wilhelm sent his army marching to France via Belgium. His passable command of English earned him a post as translator for the British Royal Naval Division stationed in Antwerp, where the Allies hoped to stop the German war machine before it got up to speed. The Allied commanders had reason to believe they might succeed. In the past, Antwerp had proved nearly impregnable, ringed by a series of earthen and stone fortresses collectively known as the National Redoubt.

But when the Germans arrived in August 1914, their Big Bertha guns effortlessly vaulted Antwerp’s medieval defenses. Bomb-laden zeppelins sailing far above defenders’ bullets dropped their payload on the city’s center. By September the Allies’ chances looked bleak.

Things were not that bad for Varendonck, all things considered. His post kept him far from the front while most of the people he was tasked with translating for were occupied with battle, leaving him time to finish his original pedagogical thesis. By early October Varendonck’s scientific investigation of educational processes in Belgium was ready to send back to his advisers. Unfortunately, Antwerp erupted into chaos before he had a chance to put it in the mail.

The city’s defenses collapsed on October 10, 1914. German artillery fell like a hailstorm, igniting oil tanks and apartment buildings until the entire city was one enormous conflagration. Civilians poured onto the docks of the Scheldt River, clamoring to board anything that would float. Hoping to fight another day, the Belgian army hastily retreated west, toward the Yser River.

Amid the pandemonium, the pages of Varendonck’s thesis disappeared.

In the autumn of 1914, stationed miles from the firing line near the border of France, Varendonck found himself with enough time on his hands to start a new thesis to replace the one lost in the retreat. But makeshift army barracks are not known for their research libraries, and it wasn’t immediately clear what subject he could pursue while entrenched.

By pure happenstance he was handed Sigmund Freud’s founding work, The Interpretation of Dreams, at the very moment he had nothing else to read on an unseasonably warm December day. Psychoanalysis was a new and not a very well respected field. In Varendonck’s previous life as an academic, his colleagues had steered him away from taking the discipline too seriously; in other circumstances he may well have disregarded the book altogether. But this was a different situation, with only a single book available to help pass the time.

Varendonck stayed up late finishing the last chapter of The Interpretation of Dreams by candlelight as German mortars roared in the distance. The noisy dark lulled his attention away from the page—wandering and bouncing between events occurring far away and near, in the distant past and not yet future—until he could no longer recall how or why one thought had led to the next. He realized, after escaping this gossamer-thin web of idle thoughts, that daydreaming was the ideal topic for a second thesis.

Daydreaming might appear at first glance the antithesis of global warfare. Yet an era defined by firestorms was also increasingly obsessed with the inner workings of the mind, and the Allied powers’ first stand against the German army emerged as a fitting environment for a rigorous exploration of modern mental perambulation. What else was a soldier to do at the front, in the long hours between battle, but let his mind drift elsewhere? Besides, steeped in subjectivism, the fledgling field of psychology had few rules, allowing Varendonck to make up his own.

Though The Interpretation of Dreams inspired his study, the only note Varendonck took from the text was Freud’s technique of summoning dreams from the hinterlands of the unconscious by entering into a meditative state of “uncritical self-observation.” Despite the change in tack from his original focus, Varendonck adapted his social scientific training to his new topic by formulating a more clinical approach to remembering the meanderings of his mind. He began at the end, recalling the last piece of a daydream before working backward to the start. Through this process he was able to record his dreams with stunning lucidity.

More remarkably still, what he recorded utterly flew in the face of psychological theories of daydreaming up to this point.

In 1904 the American child psychologist Theodate Smith published one of the first psychological papers on the nature of daydreams, or reveries that occur in the preconscious mind while an individual is awake. She theorized that these involuntary yet semi-self-aware visions are almost always pleasant in nature, because “if the subject of the dream becomes unpleasant, it is usually changed or the dream is banished.” The daydreams of the children she worked with followed the plots of their favorite bedtime stories, with the youngsters unconsciously casting themselves as the heroes. Four years later, Freud penned his own examination of adult daydreams, reaching many of the same conclusions. He compared the arc of daydreams to the plots of popular novels in which the hero always wins. The daydreamer they conjured imagined herself as impervious to tragedy.

Varendonck’s mind, bludgeoned by the sound of German artillery that rang in the ears long after falling, worked a little differently.

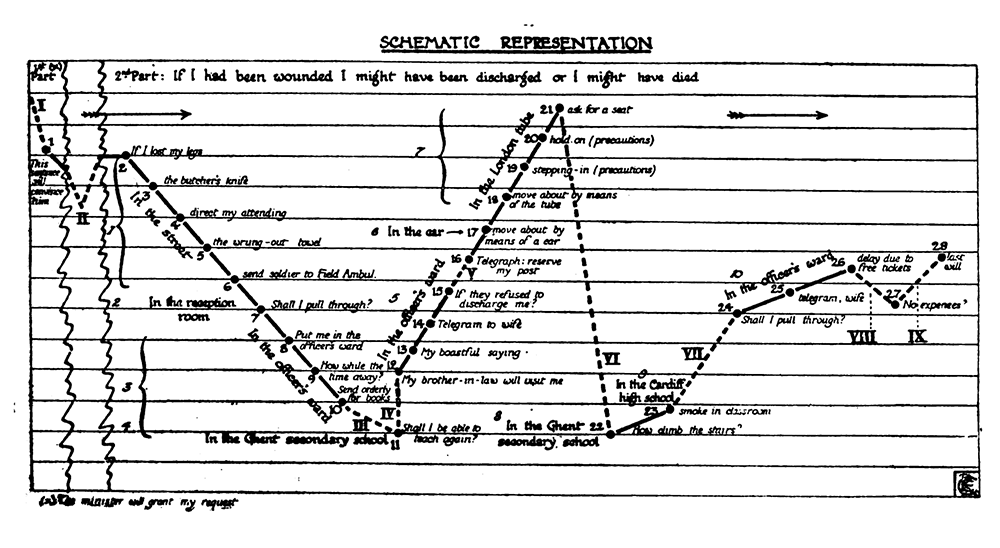

“I see in my fancy my other colleague F. picking up successively two children who have been severely wounded by the explosion,” began one of his daydreams. “Next moment, I see myself lying on the cobbles in front of the butcher’s shop with both legs off above the knee. I ask the butcher (the wounded children were his) for a knife to cut off the last filaments of muscle that attach the blown-off left leg to the thigh.”

Far from previous conceptualizations of the impervious ego, Varendonck’s daydreamed self-image was victim to one of the most brutal injuries one can suffer in war and still survive. Losing his legs wasn’t the only setback inflicted by his mind. Bureaucracy, that other horror of war, proved a second source of angst and anxiety for his daydreams. A run-in with a rude orderly serving under a particularly draconian and powerful head nurse, Lady V., inspired one such example. Varendonck obsessed over the event, consumed by visions of possible outcomes. “I am talking to Lady V., and relate the events,” he recalled. “Perhaps she will offer to send the man back to his regiment. I shall simply require a slight disciplinary measure. But what if she sides with him? One never knows.” His daydream spins into wild speculations. Should he write the report? Would writing the report be a waste of time? If he did write it, how could he best convey it to Lady V.? Should he send it to her at all? These and other such questions led him down the never-ending corridors of the labyrinth that is the wartime paper trail.

But it wasn’t only the contents of Varendonck’s daydreams that smacked of war and the modern age it catalyzed. Their very structure appeared splintered, constantly shifting in time with the past recalling the future, the future the present, and so on. Freud and Smith’s unidirectional narratives of popular novels and children’s books were entirely absent.

Varendonck moved seamlessly from one place and time to another in the vision where he lost his legs. “I am in a field-ambulance reception room (I do not know how I arrived there),” he wrote. He is abruptly transported to the London Underground, where a fellow passenger refuses to give him his seat, then to a classroom where he imagines himself teaching one day, and back in time again to the hospital bed where he asks the doctor to tell him honestly if he has a chance of recovery.

In our contemporary moment, playing temporal hopscotch may not seem like a great revolution. But when Varendonck began his study, the mutability of time had only just come into vogue. First proposed in 1905 by Albert Einstein in his theory of special relativity, the idea that time was subjective was soon adopted by literature’s modernists, notably Virginia Woolf and James Joyce. Varendonck’s wartime daydreams, recorded shortly after he experienced them, affirm the pervasiveness of this new sense of time defined by rupture rather than continuity.

Saint Augustine often warned his flock against daydreaming, preaching, “Ne subtracto fundamento rei gestae, quasi in aere quaeratis aedificare” (Do not subtract the basis of their achievement, as you seek to build up in the air). In other words, don’t build castles in the air; they’re liable to get blown away by the first gust of reality. Like the author of Confessions, most psychologists believed daydreams too diaphanous to last.

But with paper and ink, Varendonck managed to add some solidity to these otherwise ethereal building blocks. Imbuing the intangible with substance enabled him to perform a metaphorical vivisection of his daydreams, slicing them into increasingly atomized component parts.

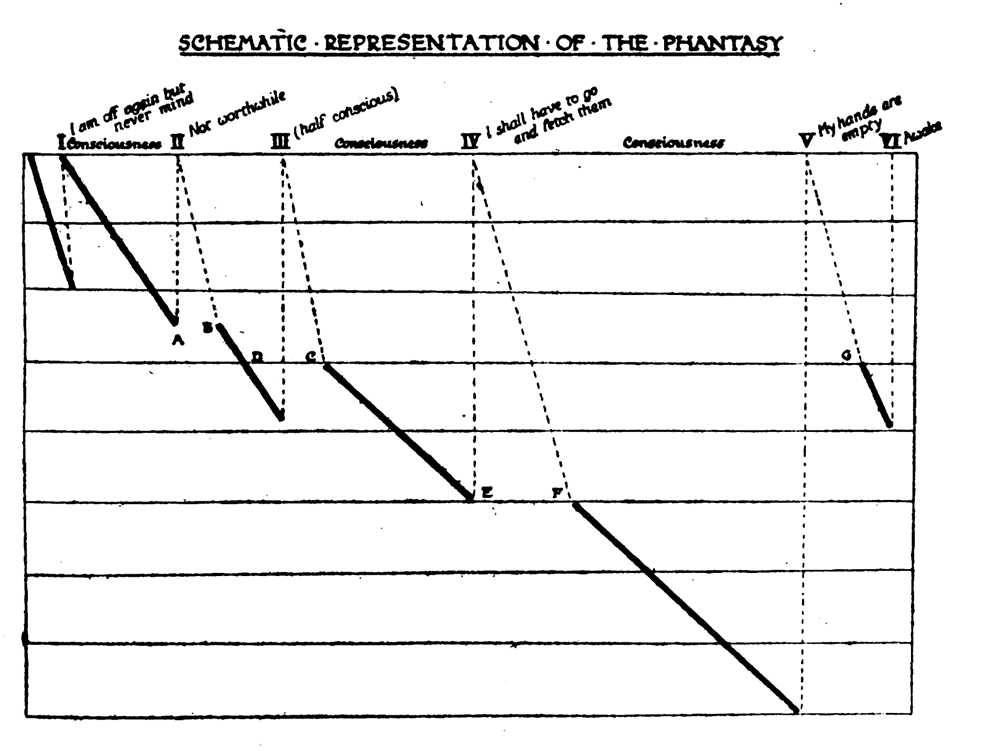

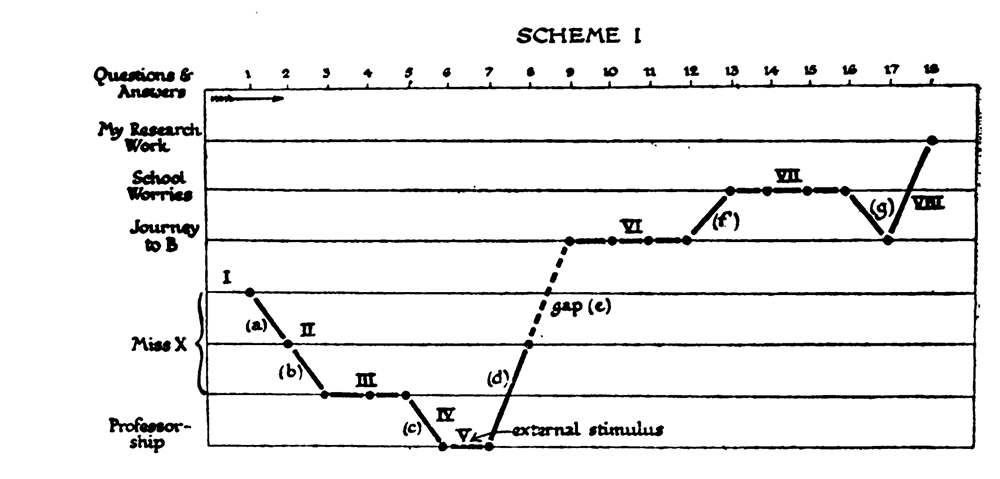

He created a system to dissect his own dreams. Step one was identifying the questions posed within a given daydream, as well as their answers. One daydream about a train ride home during leave led him to wonder, “If I have no time to lunch before catching the train, shall I have a sandwich in it?” To this his daydreaming self replied, “No; too vulgar.” Likewise, his daydreams about having his legs blown off raised the question, “What if one of my legs is not quite detached?” to which he replied to himself, “Ask for the butcher’s knife.”

Banal and brutal alike, this initial deconstruction allowed him to identify the underlying desire in each of these cause-and-effect relationships. Eroticism, for instance, accounted for a daydreamed conversation about a wealthy refugee’s daughter. Hope, on the other hand, was the essential characteristic of his waking fantasy that his thesis would be reviewed and approved in times of war. Seemingly basic, the true insight of these observations was not the underlying emotions but that they could be identified and fixed in words.

These observations allowed him to transform his daydreams into data sets that could be plotted on a graph. As if tracking seasonal rainfall or the price of a stock, the Y axis represented his underlying desires while the X axis measured the progression of thoughts. The amorphous matter of daydreams was taken apart and refashioned to fit the shape of the age, just as the lives of Varendonck and his fellow soldiers, ricocheting between boredom and action and fear, were subsumed into the story of war.

Varendonck spent the remainder of the war dug in along the Yser River, where his studies were sporadically interrupted by German shells, but not enough to deter him entirely. When the Armistice came, he had finished his thesis. After his advisers approved it and his degree was granted, he sent it to Allen & Unwin in London to be published under the title The Psychology of Day-Dreams.

In his thesis’ conclusion, he wrote that, like their nocturnal counterparts, “daydreams betray preoccupations with unsolved problems, harassing cares, or overwhelming impressions.” But unlike dreams conjured in sleep, daydreams are concerned with the immediate and the topical, and “all strive toward the future; they all seem to prepare some accommodation, to obtain some prospective advantage for the ego; they are attempts at adaptation: such is their biological meaning.” Daydreams, in Varendonck’s mind, took on the strange yet vital task of learning how to live with, through, and after the inevitability of conflict.

Varendonck later became a professor of clinical psychology at the Université libre de Bruxelles, where his work was very well received. In one review highlighted by scholar Susann Heenen-Wolff, the British experimental psychologist J.C. Flügel lauded The Psychology of Day-Dreams in The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, going so far as to say, “It will probably occupy an important place in the history of psychology as a pioneering work in an interesting and important area.”

Heenen-Wolff also notes that Anna Freud translated a portion of the book for publication into German; Sigmund Freud himself penned a complimentary introduction for this edition, writing, “This book by Dr. Varendonck contains a significant novelty and will rightly arouse the interest of all philosophers, psychologists, and psychoanalysts.” It was high praise from the founder of the field.

Knighted by the nobles of psychology, Varendonck rode the lecture circuit and published widely. He was inducted into the Dutch Association for Psychoanalysis as an “extraordinary member.” Unfortunately, it was a short ascent, followed by a steep drop.

In 1922 Varendonck published an article titled “A Contribution to the Study of Artistic Preference,” a thinly veiled analysis of his ex-wife’s fantasies as expressed through her favorite arias. It was viewed as nothing more than an essay on his failed marriage and met scathing criticism. Even Freud himself wrote the journal’s editor to say, “Varendonck’s work on his marital misconduct should not have been accepted.” The journal’s editor hastily replied with contrition: “Maybe it was a mistake that I accepted Varendonck’s essay. I was influenced by your high opinion of him, while I, I confess, think much less of him.” Shortly after Varendonck was summarily dropped from the upper echelons of psychology. His works were no longer published. He ceased to be invited to prestigious conferences. Invitations to cocktail parties at the Viennese apartments of psychology’s luminaries no longer arrived in his mail.

Varendonck might have turned things around if he had had more time. Unfortunately, he never had the chance to try. In 1924 he died from complications during an otherwise routine gastric ulcer operation. Animus and past accolades alike were forgotten, propelling his early analysis of the nature of daydreams to the outer periphery of history until it nearly disappeared altogether.

Perhaps it would have ended up there anyway. Sharing many of the foibles and fallacies of early psychology, The Psychology of Day-Dreams is far from perfect. Centered and based on the experience of a white male not only in war but also in life writ large, it could be said that his theories discounted and excluded many. But the key to his insight lies in that it is a portrait of the exact moment when daydreams were transformed from castles in the air to stone fortresses resembling not what we wished but what is.