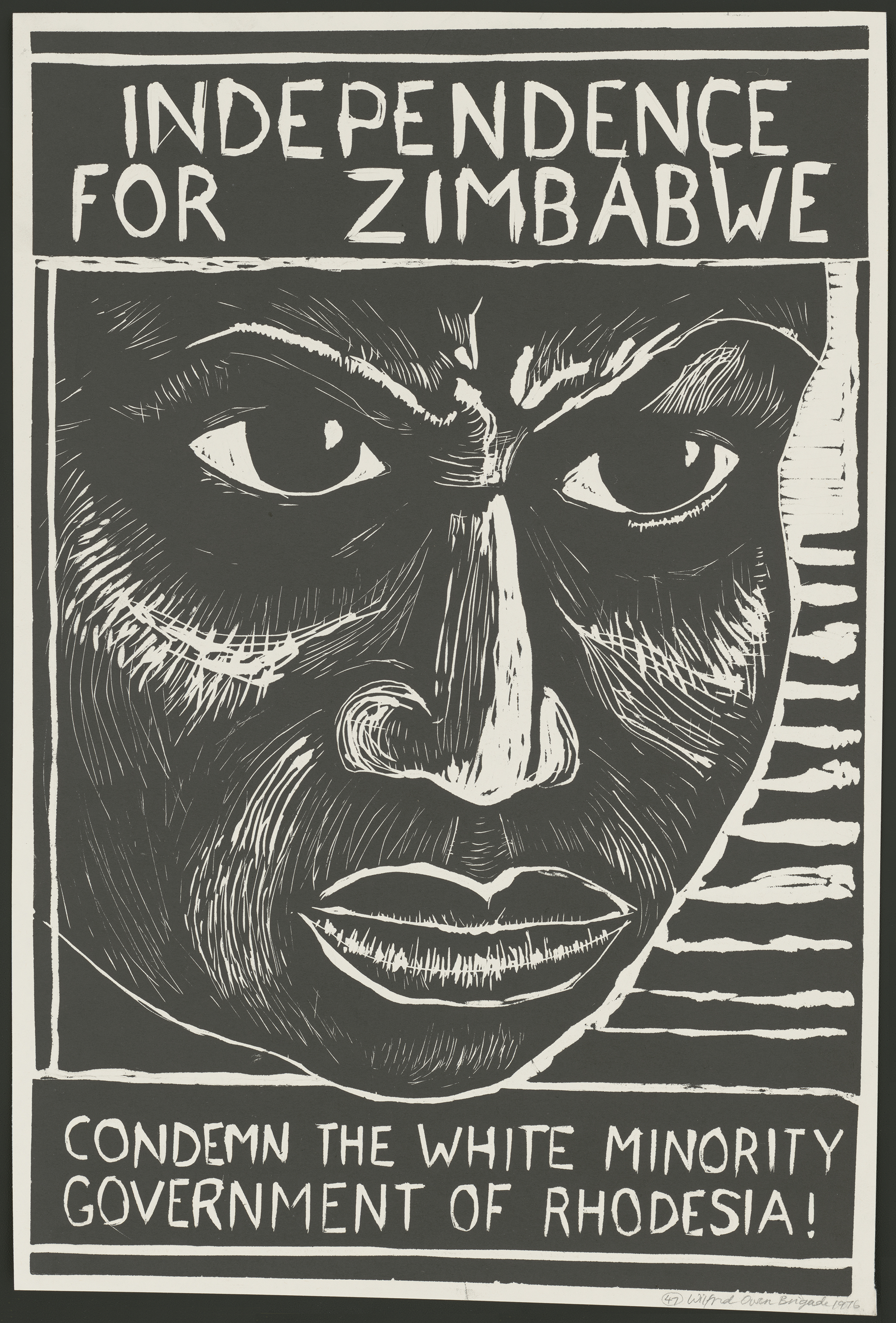

Independence for Zimbabwe poster by Leon Klayman and Wilfred Owen Brigade, 1976. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

On a sticky April night in 1980, throngs of people gathered inside and around Rufaro Stadium in the township of Mbare in Harare to await the arrival of Bob Marley and the Wailers. The most famous dreadlocked man in the world was the sole international artist invited to perform at the Independence Day concert celebrating Zimbabwe’s liberation from colonial rule.

Guerrillas had listened to Marley’s freedom-laden lyrics on cassettes smuggled into the country; the chance to see him live was not only a dream deferred finally come true but a hopeful foretelling of the future their comrades had died for. “It was a moment I fully savored,” former soldier and later politician Christopher Mutsvangwa told Al Jazeera in early 2020. “Tears of pain-filled delight rolled down my cheeks.” So frenetic was the excitement over the scheduled performance that cascades of the more than forty thousand people crushed the temporary gates and barriers meant for crowd control. In a state of panic, police tear-gassed parts of the crowd; members of Marley’s entourage, including his wife, Rita, got caught in the smoke. Only after the crowd had calmed down a bit did Marley come on stage, oblivious to the pandemonium but sharply aware of just how deeply his presence was felt and cherished.

The day before the concert Marley had traveled to the mountainous agricultural hub of Mutoko to visit tobacco farmers and sample some of the region's indigenous produce. During his visit to Zimbabwe, the musician spent time with the locals, choosing to stay at the Skyline Hotel, located on the outskirts of Harare and known as a haunt frequented mostly by the Black working class looking for a good time. His one-day concert was extended to two; the second show brought in about a hundred thousand people. This time there was no tear gas. Marley’s song “Zimbabwe” became a way to mark that moment and an unofficial national anthem, one filled with diasporic legacy and national pride.

Music and democracy have always fed each other in this southern African country. Before colonization, the land that would become Zimbabwe was covered in a palimpsest of kingdoms, separated by time and lineage. One of the most researched is the Mwene Mutapa Empire, a nation with a substantial military, a belief in Nature’s providence, and respect for women in authority that existed from the fourteenth to the seventeenth century and covered more than 260,000 square miles, stretching into Mozambique.

For the people of Mwene Mutapa, music was an expression of freedom and a cultural spine that kept different segments of their society connected. A new moon during Chivabvu (May) called for communion with ancestors, and drums would beat ceaselessly for seven days while the king meditated in seclusion. During Gunyana (September) the king and his advisers would visit the royal graves and contact past rulers through a spirit medium as drummers sang and chanted. Songs could also warn when trouble was close to home.

Music played such a central role in African communities that many colonizers banned the use of musical instruments, fearful that messages of revolt could be transmitted alongside melodies. These prohibitions followed the Africans who were forcibly taken elsewhere. In 1740 South Carolina enacted the Negro Code, forbidding the enslaved from “using or keeping drums, horns, or other loud instruments, which may call together or give sign or notice to one another of their wicked designs and purposes.” The British arrival in Southern Africa and the subsequent displacement of indigenous groups almost destroyed centuries-old civilizations through the mass killing of “dissenters” and religious and economic disenfranchisement. Yet music remained an integral part of how the people of Zimbabwe, now made up largely of Shona and Ndebele groups, initiated covert and overt acts of revolt against white minority rule.

In 1899 Cecil John Rhodes, the British colonizer and later prime minister of Cape Colony (now South Africa), founded the British South Africa Company under the order of Queen Victoria for the sole purpose of colonizing southern Africa, displacing its inhabitants and exploiting the mineral wealth both in the Cape and in the country whose name would be an homage to his colonial legacy, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). For over a hundred years, British subjects, on behalf of the imperial power, looted gold from Mashonaland and the mines in Kimberley, using indigenous people as disposable labor and tools for expansion. Hundreds were taken from their families during the World Wars and conscripted to fight for the British.

The U.S.-backed white, minority-led government of Ian Smith, who served as the prime minister of Rhodesia from 1964 until 1979, continued Rhodes’ destruction of Black life. Smith’s white-supremacist rule was totalitarian and expansive. He was supportive of colonial regimes similar to his own, backing leaders in apartheid Union of South Africa (South Africa), Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique), and the Belgian Congo (DRC). During the fifteen years of his rule, his military forces faced Black freedom fighters from two distinct camps: the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA), led by future president Robert Mugabe, and the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA), led by future vice president Joshua Nkomo. The two groups’ military raids, though mostly separate, were calculated and direct, using land mines to destroy roads and disrupt food and weapons transportation. They also worked closely with indigenous people, with many lending their support by offering places to hide, clothing, and, most importantly, information.

In Rhodesia, political leaders instituted control and systemic oppression of the people in numerous ways: surveillance, state-sanctioned physical brutality, segregation, and the use of internment camps that were spun as “Protected Villages.” The majority of Zimbabweans living in rural parts of the country were taken from their homes, usually in the middle of the night, and forcibly placed in these camps. This mass detainment of civilians was meant in part to create a literal barrier between freedom fighters and the people who supported and believed in their revolution.

As the government dismantled lines of communication, those fighting for liberation learned to rely on older, lyrical ways of reaching out.

In the 1930s rural teenagers started to leave home in large numbers for the pulsing cities. They gathered at small bars in segregated towns where free-flowing liquor sped up the transmission of ideas while operating outside the law. Coming from different areas as well as the surrounding colonies of Nyasaland (now Malawi) and Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), these young people brought musical traditions that eventually coalesced to form a genre known as Zimbabwe township music, or ZTM. Driven by the improvisational structure of jazz, the genre was a product of cross-cultural influences, melding musical styles such as kwela and tsabatsaba from South Africa. The tone was percussion heavy, anchored by propulsive drums and the subtle but persistent hosho (shaker). Zimbabwe township music quickly fanned across the country, becoming the mode through which an oppressed people sang about the freedom they knew would come and the defeat of the imperial power they expected. It was colorful, fervent, and hard to miss, much like the urban communities that birthed it.

The City Quads, one of the most popular bands in ZTM, was formed in the capital of Harare, then called Salisbury. A quartet featuring Sam Matambo and Sonny Sondo on lead vocals, with Titus Dan and Stephen Mtunyani alternating between drums and guitar, they sang in Shona and Ndebele. Using the languages of locals, with cleverly concealed proverbs and double entendres, their songs touched on the cornerstones of civilian life: work, being hassled by the police, more work, and survival. They released their best-known hit in 1960, “Lizofika Nini Ilanga Lenkululeko?” (When Will the Day of Freedom Come?):

Lizofika nini ilanga lenkululeko

Lizofika nina ilanga lenjabulo

Abantu abansundu bayahlupheka

Kudhala, kudhala, kudhala.

When will the day of freedom come

When will the day of happiness come

Black people are suffering

For so long, for so long, for so long.

By that time the British government had started to monitor musicians in Zimbabwe, aware of how easily artists could incite revolt with words that many of the colonizers did not understand. Before permitting the song to be played on the radio in Salisbury, white supervisors working at the African Service of the Federal Broadcasting Corporation (where Matambo also worked) asked for a translation. After hearing the lines detailing Black struggle, they demanded that the artists cut them out of the song. The version that subsequently made it to the airwaves spoke of Black people’s failure to self-govern and credited their survival to benevolent white do-gooders on a Christian mission. Yet after several months of circulation, “Lizofika Nini Ilanga Lenkululeko?” was still banned.

Faith Dauti, one of the few women who became famous on the Zimbabwe township music scene, started off singing in a band with her cousins known as the Milton Brothers, and went solo a few years later. The title of her 1952 song “Nzve” means “to evade.” When used in Shona—its sharp, comedic inflection is lost in translation—the word denotes slyness and skillful maneuvering to escape capture or danger. Nzve is a playful word, and Dauti still found a way to make it pointed, deliberate, and acerbic, casting the evasion of the police as something that was both humorous and necessary for the listener’s safety. The song highlights the everyday realities of the Black urban working class, who had to navigate police interactions that were equal parts nuisance and terrifying.

Written lyrics are hard to come by—Black musicians were rarely allowed entry into recording booths, and censorship and mass surveillance made archiving music, poetry, and literature difficult. The words of local and regional hits were often seen only by composers and later remembered by audiences. Preservation relied on those shared memories. When I asked my father if he remembered “Nzve,” he furrowed his brow and recited a single standout line that he had sung in his youth: “Ndikati nzve, ndamuona / Ndikati nzve ndamuona.” Roughly translated, it runs, “If I duck / Swerve / Hide, I have seen him / If I duck / Swerve / Hide, I have seen him.”

Both ZANLA and ZIPRA were invested in freeing Black Zimbabweans from Smith’s white-supremacist rule, even as they fought each other for land, power, and influence across Shona and Ndebele lines. The music of that era rarely paid heed to the volatile relationship between the factions, however, and instead called for unity across all ethnic groups in fighting an insidious and foreign common enemy. As radio communication was widespread in 1950s and 1960s Zimbabwe, music found its way to the freedom fighters hiding in the Eastern Highlands and training at camps in Zambia and across the border in Mozambique. Cut off from urban centers, these fighters also found encouragement in the songs sung by people in the countryside and by those who had escaped the internment camps.

Although aiding and uplifting the fighters could lead to death, civilians found ways to support them through music, turning herding songs into war chants for beloved military leaders. “Tevera Mukono Unobaya Dzose” (Follow the Sharp Horned Bull Who Can Pierce All Others) was a favorite of fighters and civilians alike, with the animal representing controlled strength, capable of being still and also exhibiting brute force. The song was especially loved by ZANLA military commander Edgar Tekere, known as 2-Boy to his soldiers. It was Tekere—who went on to become a popular politician in free Zimbabwe—who invited Marley to perform at the Independence Concert.

“Tevera Mukono Unobaya Dzose” was about the strength of the leaders on the front lines, an encouraging war cry that sought to uplift and inspire. When sung by a single herder, it was meditative, lulling both the singer and the listener into steady forward movement. When shouted in unison, it was a road map marking the path home, building into a crescendo that ended only when voices were hoarse and emotions were raw. You would not hear the song on the radio, but even now my parents, grandparents, and uncles remember what it sounded like during wartime. The message rang out across the country: wherever you were, you followed the sharp horned bull. The song had been known long before the Europeans came, and after they arrived it morphed to express an urgent message in need of concealment.

In 1965, a year into Ian Smith’s prime ministership, Rhodesia signed the Unilateral Declaration of Independence, which meant the colony was no longer part of the British empire and now existed as an unrecognized state. Musicians had seen neighboring countries like Malawi and Zambia earning independence and foretold the changes coming to Zimbabwe; they gave the Smith government early notice of the true independence that would come with the arrival of self-rule fifteen years later.

Thomas Mapfumo is credited with popularizing and, in some circles, creating chimurenga music in the early 1970s. Chimurenga is a Shona word meaning “uprising” or “small fire.” African instruments such as the marimba and mbira were prominent in chimurenga songs and their narratives of struggle and uprisings. Mapfumo’s song “Hokoyo” (Watch Out) signaled to the white minority government that nothing was going to keep revolution away.

Hokoyo!

Hokoyo!

Hona banga ndinaro,

Hooo! katemo ndinakoooo.

Hoooo!

Ndini Karikoga Hooo! Heeehh! Aaaahhh!

Hokoyo!

Watch out!

Watch out!

Look, I have a knife

Look I have an ax

Watch out!

It’s just me!

Watch out!

Released at the height of chimurenga’s popularity in 1976, “Hokoyo” also provided the title for Mapfumo’s first full-length album, which solidified his position as the bard of Black Zimbabweans’ tribulations. In 1979 the song’s clear call for mass mobilization led to his imprisonment for three months. Two years before his arrest, Mapfumo played in a band known as Wagon Wheels that gave Oliver Mtukudzi his first big break. Mtukudzi’s first single, “Ndipeiwo Zano” (Give Me Advice), delivered in his singular gravelly tone, spoke of the stifling mundanity of hardship and despair Black people faced. Though not as incendiary as “Hokoyo,” “Ndipeiwo Zano” distilled public grief into a song that provided both comfort and purpose for those ready for the war to end.

Comrade Chinx, another beloved artist, was a freedom fighter and also coordinator of the ZANLA choir, which traveled from base to base singing to the troops. After independence he became a high-profile musician, releasing his best-known song, “Hondo Yeminda” (War for Land), at the same time the land reform program was gaining traction. This was a government-instituted policy that aimed to return land to indigenous Zimbabweans that had been taken from them and their ancestors during colonization. It was also a means to equalize land ownership in a country where prime acres were owned by the white minority population. Overseas politicians, such as British prime minister Tony Blair and U.S. president George W. Bush, saw the move as antiwhite. For millions of Zimbabweans, it was a return of land that should never have been taken away in the first place.

So often people speak of the boundless reach of music, its ability to bridge racial gaps and transcend inequity, yet when it comes to Black resistance so many of the most beloved genres exist because of restrictions. The sweeping emotional force of American gospel emerged because hymns were not simply about longing to be good so the next life would be bountiful but expressed a desire for freedom both now and in the future. The blues were the sounds of broken hearts made audible; Brazilian axé music was a reconnection to interrupted African ancestry. Reggae was powered by prohibited melodies turned into movement; Zimbabwe township music and chimurenga offered a nationalism that was both local and pan-African, the inevitable result of limited mobility and a freedom unavailable to those whose skin was black.

In the forty years since Zimbabwean independence, leaders reminiscent of those invoked in the Nigerian musician Fela Kuti’s blistering “Beasts of No Nation” have broken the country. Mapfumo left Zimbabwe in the early 2000s, after his music was called an attack on the government of President Robert Mugabe. In August 2019 political commentator and comedian Samantha Kureya was assaulted—by people many believe to have been law enforcement agents—after voicing criticism of Emmerson Mnangagwa’s administration. The Zimbabwe of today is a youthful country, with nearly 68 percent of the population under thirty-five, and they know only a Zimbabwe that has been wrecked by greed and an inflation rate of 761 percent as of August. Reliable access to food, electricity, and water is attainable only for the wealthy; civil servants such as doctors and teachers are constantly on strike for increased wages.

Democracy changes, and the word freedom shifts depending on the speaker and those spoken to. When democracy fails, it’s music that echoes across the land, from the Eastern Highlands all the way to the township bars. And when democracy returns, it’s music that fills up the stadiums and tells stories of the battlefield wins that no one saw. Zim dancehall, inspired by the popularity of reggae and dancehall, is the music that now echoes from omnibuses, kiosks, and clubs. Jah Prayzah, whose melodies express the kinship Zimbabwean artists continue to feel toward reggae decades after the Bob Marley independence concert, is currently one of the most well-known performers in the country. His song titled “Hokoyo” differs from Mapfumo’s in that it warns not of radical change but of the nhamo (trouble) that will visit the listener, be it from the jealousy of others or the environment surrounding her or him. The current disarray in Zimbabwe makes something as trivial as singing about the individual a political act rooted in the need to survive. Because trials are inevitable, the song urges perseverance, sunga dzisimbe. This too will pass.