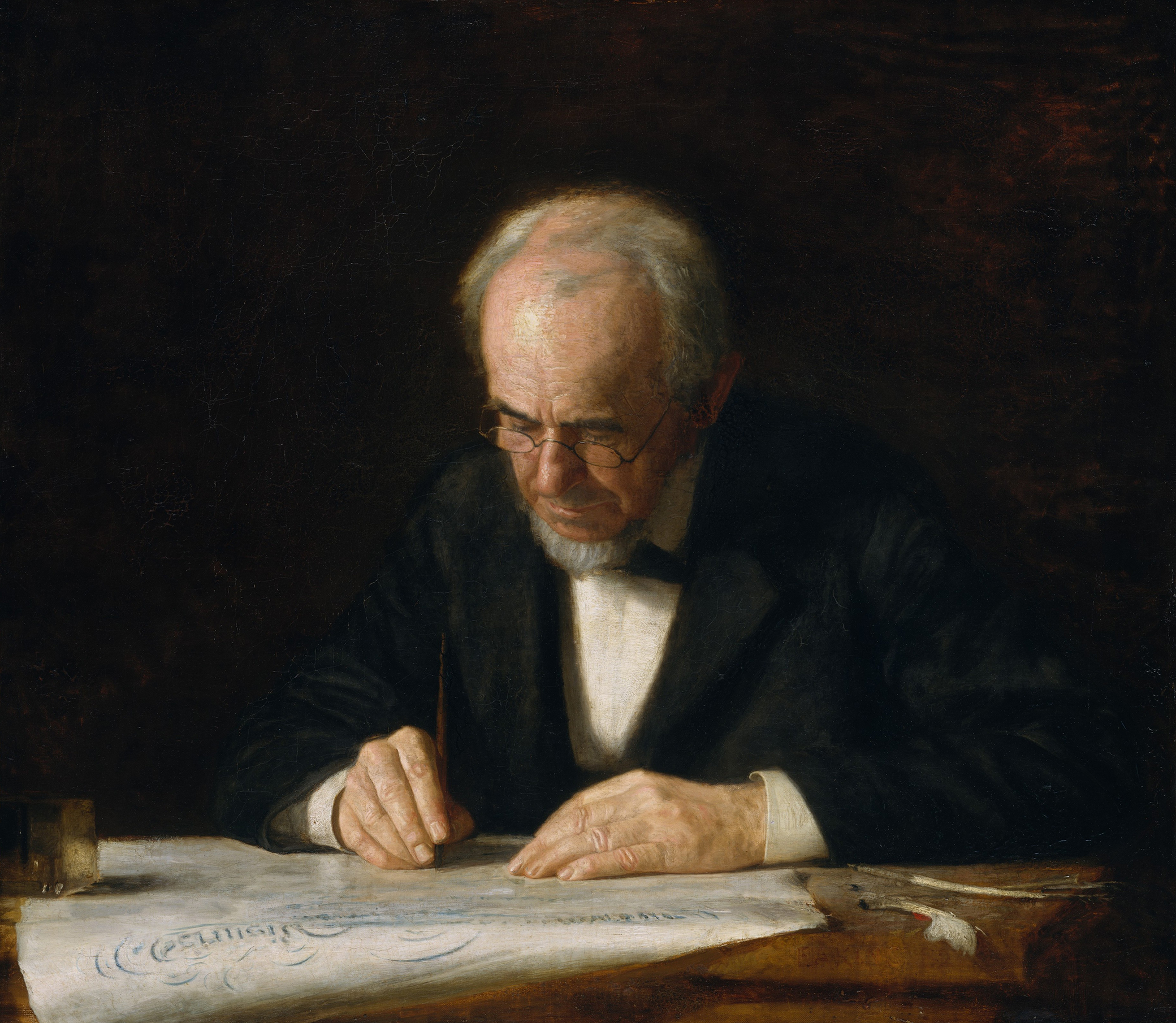

The Writing Master, by Thomas Eakins, 1882. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1917.

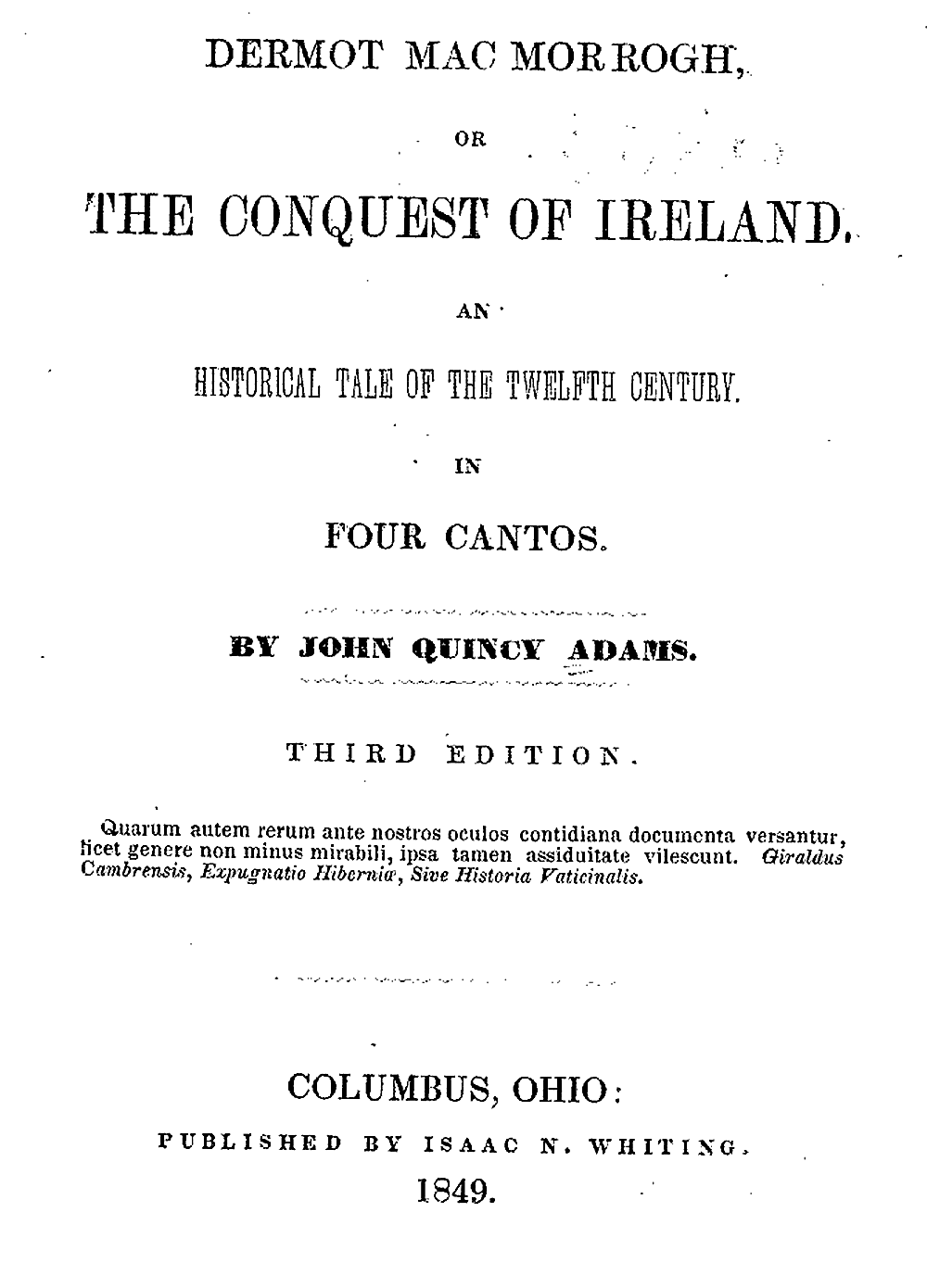

In February 1831, some two years after suffering a humiliating defeat in his presidential reelection bid, and two weeks before assuming office as a freshly minted Massachusetts congressman, John Quincy Adams sat down to write an epic. “I began this morning a Poem,” he wrote in his diary, “the conception of which is amusing but requiring more continuity of purpose, more poetical imagination, and more command of language and power of harmony than belongs to me.” Despite his professed sense of inadequacy—a sense he carried through all his writerly endeavors—Adams wholly committed himself to the project. He sometimes composed in the early hours of the morning before getting out of bed or muttered spontaneous verse to himself on long walks around Washington, DC’s Capitol Square, which he would later transcribe before dinner. The following year, Adams would publish the result of his ramblings: Dermot Mac Morrough, or, the Conquest of Ireland, a mock-historical epic of 266 ottava rima stanzas, in four cantos.

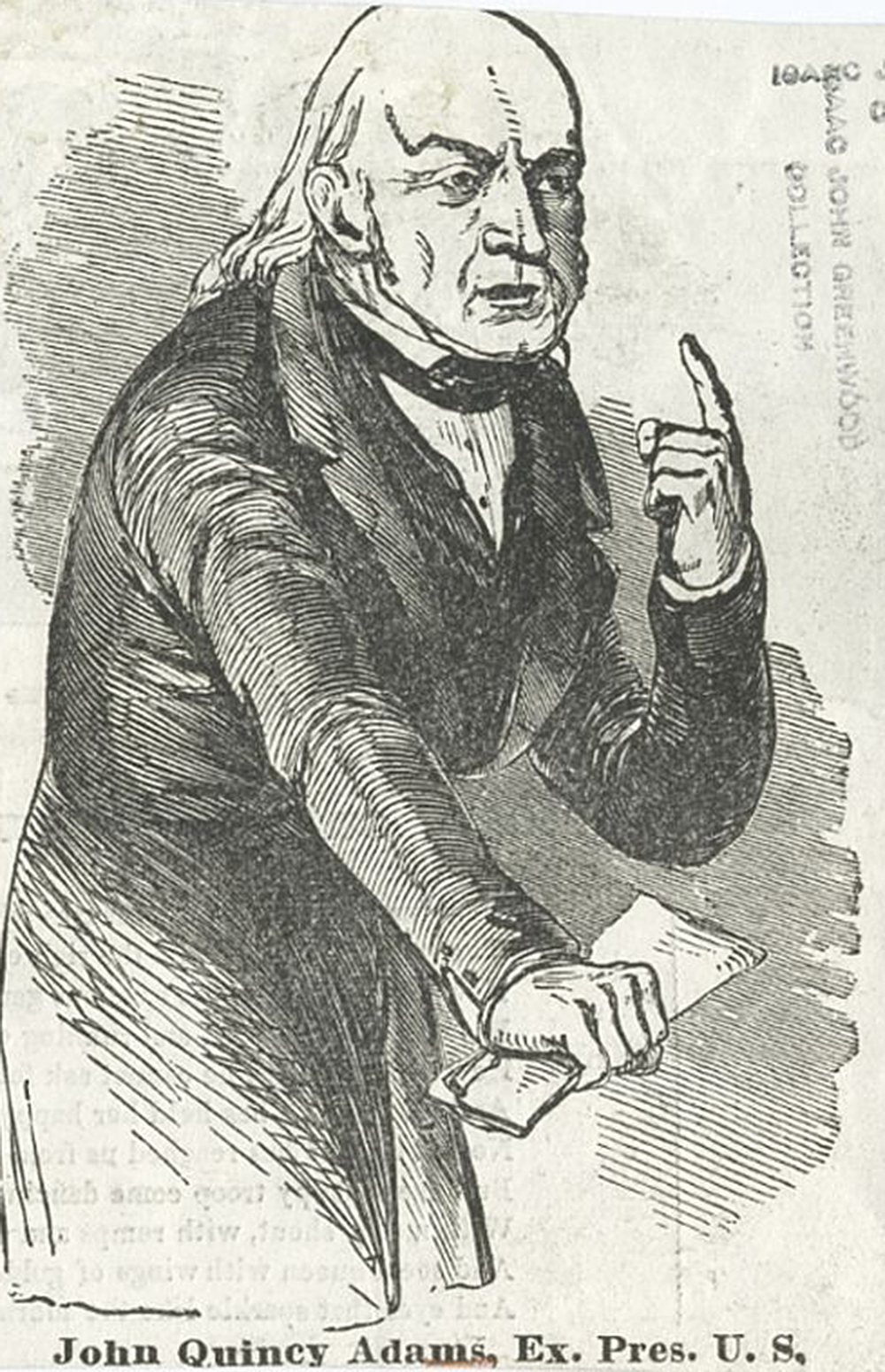

When Adams conceived of the work, he was still smarting over Andrew Jackson’s 1828 victory. To Adams and his supporters, the unscrupulous Jackson heralded a dangerously chaotic set of norms in American politics. The latter’s ostensible disrespect for legal precedent, his cult of personality, and lack of political and moral vision (as well as his penchant for lethal dueling) could not have run further afoul of the high-minded anti-factionalism to which Adams laid rhetorical claim in his political career. Jackson, meanwhile, wielding unprecedented amounts of campaign cash, had driven his supporters into a frenzy over the patrician Adams’ record, charging him, among other anti-American heresies, with monarchism, European-style decadence, Masonry (false, and pointedly ignoring the fact that Jackson actually was a mason), federal overreach, and perhaps most fearfully, the specter of abolitionism. Although the ex-president had presided over a peaceful, economically stable, and bureaucratically well-managed four-year term, he had accomplished little of substance, and was walloped by the ex-general by an electoral-vote margin of 178-83. Resigned, a defeated Adams spent the final weeks of his presidency tending quietly to vegetables, fruit trees, and herbs in the White House garden.

Adams now turned to poetry, a source of both amusement and sustenance throughout his life and career. His earlier efforts had run the formal gamut, including a youthful Romantic paean to the cliffs of Dover, a love poem to an idealized, indifferent beloved, satirical sketches of the young society ladies of Massachusetts, a playful account of his maid’s unexpected pregnancy (based on a true story, and concluding happily with a baptism and marriage), even an ode to a particularly revealing dress, which his wife Louisa characterized as “the sauciest lines I ever perused.” But despite his occasional (and comparatively modest) forays into prurience, Adams was most at home in a didactic, religious mode. The better part of his poetic output consists of short, lyrical expressions of spiritual devotion—the pious hymnals that would eventually be collected in the posthumous Poems of Religion and Society, the anthology upon which Adams’ modest nineteenth-century reputation would rest. Adams’ best-known poem at that time was 1841’s “The Wants of Man,” a measured consideration of heavenly and earthly pleasures. (“My last great Want—absorbing all— / Is, when beneath the sod, / And summoned to my final call, / The Mercy of my God.”) It would later appear in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1874 edited anthology Parnassus alongside Wordsworth, Milton, and Tennyson, in a particularly botched attempt at forecasting the canon.

Dermot was a much more ambitious project, and in some sense an inevitable one. Adams had spent much of his life haunted by a sense of missed vocational opportunity, having foregone a life of literary seclusion for a duty-bound career in the public sphere. “Could I have chosen my own Genius and Condition I should have made myself a great Poet,” he noted in his diary in 1816. “As it is, I have wasted much of my life in writing verses; spell-bound in the circle of mediocrity.” Adams’ regretful melancholia, sedulously chronicled in his diary throughout his life, was never unaccompanied by frequently brutal assessments of his own poetic talents, the nagging sense that, free from public obligations, a poetic career would have been doomed to failure regardless. Dermot provided Adams an opportunity to evaluate his own self-estimation, to see, in the wake of an ineffectual presidency, if he might more adequately serve the nation through instructive verse.

The setting for this moral tale was to be, oddly, twelfth-century Ireland. Adams encountered Dermot’s historical outline in David Hume’s History of England, which he quotes indulgently in the poem’s preface. The story—at least in Hume’s rendition—involves a local Irish king, the titular Dermot, who angers a neighboring ruler by kidnapping his wife (a practice that, Hume helpfully explains, was “usual among the Irish”). The incident sparks a treacherous appeal to the English king, Henry II, to come to Dermot’s aid, which results, ultimately, in the wholesale annexation of the island.

Despite the obscurity of its setting, the poem’s links to Adams’ recent electoral frustrations would not have been lost on a contemporary audience. The figure of Dermot, to begin with, was unmistakably Jacksonian, willing to betray his own country for the sake of personal political gain, and a model what Adams called “insupportable tyranny.” More crudely, his wife-stealing hinted at two unconventional marriages in the Jackson administration. The president himself had married his wife while she was still married to her first husband, leading to charges of bigamy from the Adams camp (Jackson would partly blame these allegations for her premature death in 1828). And in what became known as the Petticoat Affair, secretary of war John Eaton incurred the wrath of Washington’s polite society by allegedly carrying on an affair with the wife of an absent, alcoholic naval officer. Adams takes great care in his poem to warn against reading Dermot as a contemporary political allegory, but the excessive effort he makes to do so only belies his point:

Against all this, I enter my protest:

Dermot Mac Morrogh shows my hero’s face;

Nor will I, or in earnest or in jest,

Permit another to usurp his place;

And give me leave to say that I know best

My own intentions in the lines I trace;

Let no man therefore draw aside the screen,

And say ’tis any other that I mean.

His readers, of course, would know exactly what he meant. But if Adams couldn’t resist lacing Dermot with the occasional political cheap shot, he was equally, if not more invested in the poem’s more universalizing moral didacticism. The commonplace ethical principles it espouses are those that Adams always viewed as his public duty to promote. “It is intended…as a moral tale,” he writes in the poem’s preface, “teaching the citizens of these States of both sexes, the virtues of conjugal fidelity, of genuine piety, and of devotion to their country.” While the themes of “a country sold to a foreign invader by the joint agency of violated marriage vows, unprincipled ambition, and religious imposture” reminds one unmistakably of Jackson, they’re not inconsistent with the moral pose Adams assumed in his poetry and political life. While it would be easy to read Dermot as a petty barb at his political enemies, it’s ultimately impossible to see it characterized by anything other than the attributes Adams preached in his political career: devotion to personal virtue and public duty, even when it’s self-sabotaging (as was so often the case for Adams).

Contrary to his predilection for such stony-faced moralizing, and his seemingly accurate self-diagnosis as a “cold” and “austere” man, Adams envisioned Dermot as comic, “mock heroic,” as he records in his diaries. To suit his purposes, he chose to write in ottava rima, the poetic form popularized by Lord Byron in Beppo and Don Juan. Adams had been familiar with Byron for two decades, and while he admired the poet’s ingenuity and technical facility, he cringed at Byron’s licentiousness. There was much in Byron’s work, Adams had to concede, that was “disgusting.” Aside from such prudish reservations, though, Adams recognized an opportunity in Byron’s use of ottava rima—a pithy, eight-line stanza that culminates in a summative, and often ironic, couplet. “The stanza makes it epigrammatic,” wrote Adams. “This is the character of all composition in stanzas. Serious or gay, they should all end in a point.” If the concluding couplet of the stanza lent itself to Bryon’s quotable, sardonic witticisms, he reasoned, why not to more dignified moral aphorisms?

And so he used both, at one moment earnestly wrestling with theodicy by addressing an apostrophized “Divine Religion” (“Oh! How canst thou behold such deeds of shame / Such crimes accurst, committed in thy name?”), the next playfully addressing an imagined offended woman reader (“The ladies then, I fear have flung aside / My book already, and I scarce can blame them…they may think the poet means to shame them.”) This tension—Adams’ inability to neatly reconcile satirical and moral impulses—feels largely responsible for consigning the poem to the historical dustbin. The problem is made apparent when, for instance, he tries at once to provoke readerly outrage for the woman Dermot kidnaps at sword point and impishly chide her (and by extension, women more generally) for trying first to gather up her jewelry: too enamored of comedic possibility to deliver a sententious lesson, too intent on airless edification to find room for humor.

Adams’ assessment of this fault is unexpectedly, if typically, trenchant: “I began my poem with the intention of making it comical, but as it advances it has made me serious even to sadness. The action and the actors are too detestable for ridicule, and although I have about me a large spice of biting satire, my natural sliding is into gravity, so that all my attempts at humor evaporated in the first canto.” The sobering impulse in him far overwhelmed the piquancy of whatever “spice” Adams actually possessed. What begins as Byron-lite backpedals into the more comforting contours of eighteenth-century didacticism, where Adams would always be at home. Another typical sentiment: “Alas! why shines alike [the sun’s] dazzling flame / On deeds of glory and on deeds of shame.”

This disparaging evaluation of the poem’s tonal inconsistency, however, paled in comparison to the impressive, self-flagellating litany of poetic faults Adams records elsewhere in his diaries. Dermot’s style, he wrote, “wants vivacity, humor, poetical invention, and a large command of language. – I want besides, a knowledge of Ireland…a knowledge of the manners, usages, prevailing opinions, modes of life, social habits, and dress of the twelfth century,” as well as the “faculty of inventing and delineating character, of naturalizing familiar dialogue, and of spicing my treat with keen and cutting Satire.” And this is all not to mention his avowed failure at “picturesque description: of penetrating into the inmost recesses of human Nature…and to consecrate the whole by a perpetual tendency to a pure and elevated morality.” At every imaginable level—technique, tone, depth, historical accuracy—Adams concedes that his poem is a flop.

The ex-president soldiered on, however, disregarding the reservations he relentlessly and self-deprecatingly catalogued in his diaries. By the time he finished, Dermot had ballooned to 266 stanzas, rather than the 50 on which he had initially planned. As in his political career, Adams’ penchant for being overly critical of himself masked an intense ambition. But he had no delusions as to what would motivate Dermot’s sales. “I am fully aware,” he wrote his publisher, “that the sale of it as an article of trade depends on the keenness of curiosity excited by the name of the author, the eccentricity of the subject, and the amazement that an ex-president of the United States should dare to write and publish a satirical poem.” Neither did he have any misconceptions about what to expect from critics, whom he knew would be skeptical of such a “daring” undertaking, but he couldn’t resist publication. “I have but to consider my poetical inspirations as waste paper,” he noted with a characteristic blend of conceit and victimhood in March 1831. “But if I should ever finish this tale, the temptation to communicate it, at least in manuscript, to some of my friends, will be irresistible.”

Adams wasn’t wrong about the wastepaper—again, his aptitude for self-criticism would prove to be superior to his abilities as a poet. The reviews, with few exceptions, were not kind, attacking the poem’s defects with complaints already familiar to Adams from his self-directed volleys that he might as well have written them himself. Their template was almost universal: praise for Adams the man, even Adams the politician, followed by regret that he should have tried to make a name for Adams the artist. “As a diplomatist and statesman, though not as a poet, he has gained for himself an honorable place in the history of our country,” concluded the Christian Examiner, generously and sagaciously noting that “the best and wisest of mortals are liable to mistakes.” There was a worried sense that Adams might have tarnished his public reputation by transgressing the sacred boundary between politics and art. “He is not content to go down to posterity simply as a great man,” sneered the American Monthly Review. “He wishes to be regarded as a universal genius.”

Beyond whatever mistake Adams made through the very act of writing, the more precise points of critical contention also echoed his own judgment: he moralized at the expense of genuine poetry. “All prose,” was the verdict of the Washington Examiner. “A rhyming centennial sermon,” as The New-England Magazine labeled the poem, distinguished by “yawns innumerable.” At best, the poem was regarded as “respectable,” a begrudging admission that an epic poem written by a recently defeated ex-president wasn’t quite as technically deficient as one might expect it to be.

Dermot’s unsparing critical reception would have accorded well with Adams’ sense of himself as a perennial martyr, a man out of time engaged in a futile struggle to preserve a fast-evaporating ethos of civic dignity. It’s no accident that Adams’ great historical hero was Cicero, whose struggle to maintain the integrity and institutions of a collapsing republic presented a handy parallel. (And the ex-president knew only too well how that worked for Cicero.) The poem, however, wound up a relative commercial success, selling over two thousand copies over the course of three editions (Adams was particularly relieved that its sales had resulted in no financial trouble to his publishers). Nevertheless, his ultimate verdict on Dermot, and all his ambitions as a poet, was as savage as ever. “Scarcely any man in this Country who has ever figured in public life has ever ventured into the field of general literature—none successfully,” he wrote in 1833. “I have attempted it...and [Dermot] will now be forgotten; as will be my other writings in prose and verse.”

Though he would continue writing poetry, and his most “successful” poems were yet to come, Adams had definitively answered his question concerning his own limitations. “I…have now the measure of my own Poetical Power,” he wrote shortly after completing the poem’s draft. “Beyond this I shall never attain.” Yet here, Adams’ preternatural knack for self-criticism finally failed him. For his diary itself—not Dermot—would ultimately emerge as his lasting literary contribution. Not the wildly ambitious poem that would guide a troubled nation, but the testament to its failure, the record of the poet’s thwarted aspirations. For while the diary fascinates in many ways—as historical annals, as rhetorical performance—it’s equally fascinating as a peculiar form of literary criticism, in which the author’s exasperated account of his own work’s imperfections far outshines the work itself. It may be, in other words, that Adams was more of a “universal genius” than his contemporaries gave him credit for—just don’t look to Dermot for evidence.