Electricity was one of the emblems of enlightened modernity. The “youngest daughter of the sciences,” as the philosopher and theologian Joseph Priestley defined it, offered a vocabulary and a repertoire of embodied sensations with which to articulate visions of human progress. Enlightened moderns turned the page on the nostalgic look to the past that characterized the previous centuries. Electricity was one of the tools they brandished to articulate a historical narrative that positioned them at the beginning of a new age of cumulative knowledge, material progress, and racial superiority. They conceded that the attractive properties that amber—“elektron” in Greek—acquired when rubbed had been known since antiquity but noted that only in the present had experimenters demonstrated that electricity was a universal power of nature.

One of the earliest British writers on the medical applications of electricity, Richard Lovett, regarded the phenomena of the Leyden jar, discovered in 1746, as nothing less than an act of divine revelation. The Italian scholar Ludovico Muratori similarly declared that God “reserved for our times the discovery of a most wonderful phenomenon. I mean electricity.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed that if “a person had started up, in the last century, armed with all those miracles of electricity which are now common to the meanest of our experimentalists, it is certain he would have been burnt for a sorcerer, or followed as a prophet.”

The widespread success of the new science was facilitated by a preexisting experimental culture that crossed boundaries between academic and the social realms. Academic journals and popular magazines, along with a vast variety of other texts, popularized the surprising results of a heterogeneous group of self-styled “electricians” or “medical electricians,” many of whom had just a smattering of natural philosophy and often no medical training at all. The Swiss physiologist Albert von Haller remarked in a long article on electricity that was published in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1747 that electrical demonstrations had awakened the curiosity of those who would not normally pay attention to experimental philosophy. Not only the literate but even the “ladies and people of quality, who never regard natural philosophy but when it works miracles,” became interested in electricity: Everyone wanted to see a “lady’s finger darting flashes of lightning, or her charming lips setting houses on fire.”

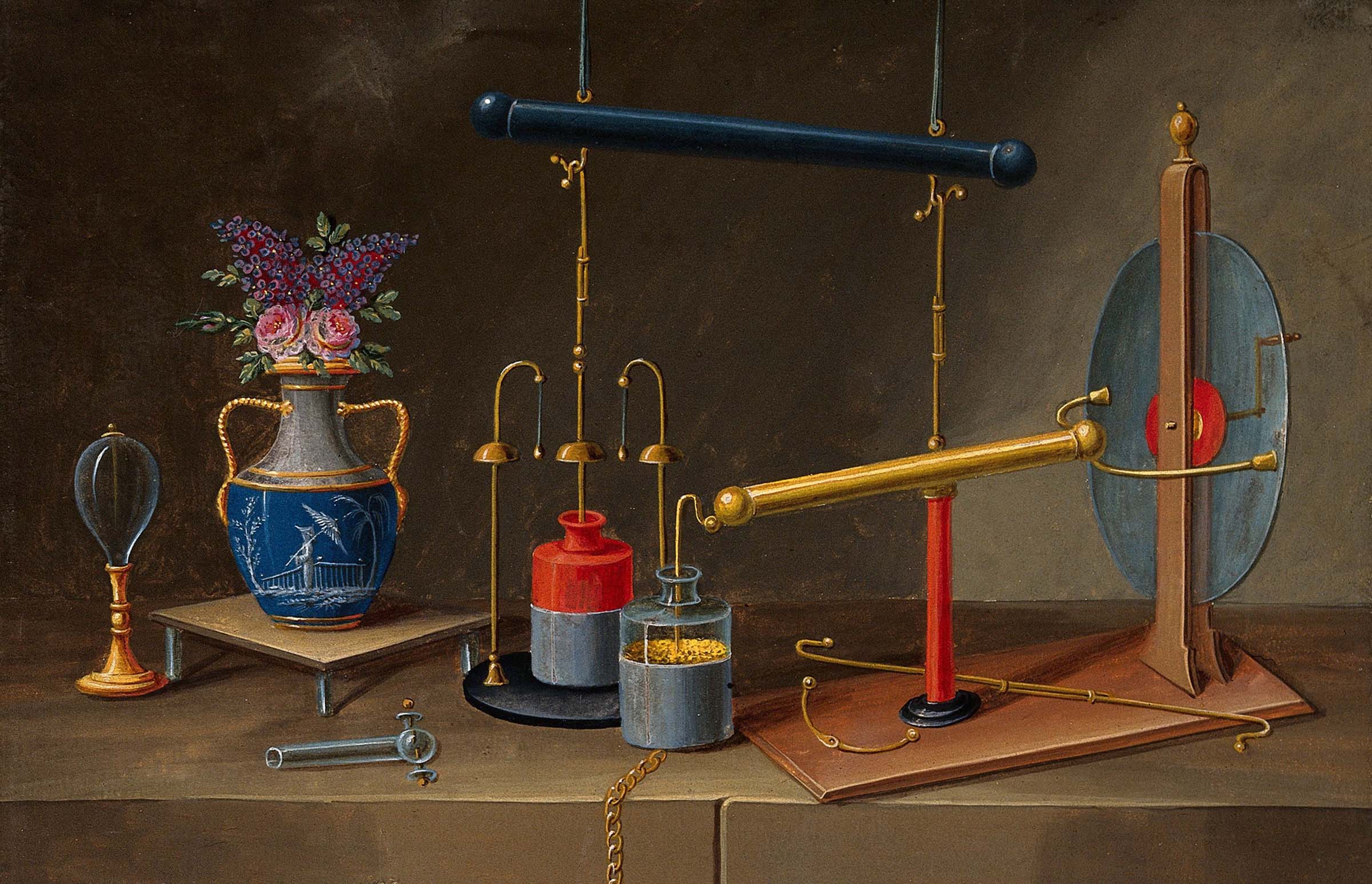

All over Europe and its colonies, electrical performances shocked and instructed. They offered sensorial evidence for the existence of an all-permeating natural substance that did not reveal itself unless properly prodded. The spectacle of electricity relied on “electrical machines” that made the newly discovered power of nature tangible. Participants in electrical demonstrations experienced with their own senses the effects of the invisible power that performers initially called “electric fire.” When connected to the electrical machine, audience members’ bodies responded uncontrollably to the passage of electricity: their hands attracted small feathers or pieces of papers without their touching them, their hair stood straight up, and their entire bodies jolted when they underwent the “electric commotion.” Only following Benjamin Franklin’s 1752 kite experiment did the association between lightning and electricity become widely accepted. Before then, there was no clear understanding of the nature of the electric matter. The popular experiments seemed to demonstrate that electricity was an ever-present natural substance, even when invisible.

Electrical demonstrators were eager for their audiences to understand that the electrical machine did not create any effect, since it only revealed the electric matter that existed in nature. However spectacular, their performances were by no means to be confused with magic tricks. In The History and Present State of Electricity (1767), Priestley admitted that the phenomena of electrical attractions and repulsions “looked like the power of magic” and so, without explanation, “and with a little art,” they could very well be used for “a deception of this kind.” However, he underscored, the electrical machine was a “philosophical instrument,” not a magician’s tool, because it exhibited “the operations of nature, that is of the God of nature himself.” Just as the air pump—another philosophical instrument according to Priestley—demonstrated that the vacuum was a natural phenomenon, the electric machine manifested the electric fire, it did not create it.

While experts debated the nature and properties of electricity without reaching consensus, electrified bodies seemed to provide evidence that electricity was an all-permeating, if still largely poorly understood, natural power. In his Essai sur l’électricité des corps (Essay on the electricity of bodies), published in 1746, French physicist Jean-Antoine Nollet offered the first comprehensive theoretical account of all known electrical phenomena, supporting his theory with a description of the physiological responses that any electrified audience member could feel. He believed that streams of electric matter—which shared some features with the substance of fire—issued in and out of electrified bodies. Participants in his lectures could use their own bodies to understand this theory: when they brought their cheeks close to an electrified object, they could feel the stream of electric fire causing a delicate tingling in their faces, and they could also see sparks issue from their fingers, hear cracking noises, and smell sulfuric odors.

Electrified bodies jolted, whooped, and gasped, potentially disrupting the codes of civility and politesse of eighteenth-century sociability. Natural philosophers whose lectures attracted aristocrats, like Nollet in Paris and Georg Matthias Bose in Leipzig, devised strategies to make the uncontrollable electrified body socially acceptable. They turned electrical demonstrations into a new kind of group dance. Lecturers led participants in explosive choreographies that showed that the loss of control caused by electrification was only temporary. Just as men and women in the group dances performed during the social gatherings of elites were assigned different steps, so the most popular electrical demonstrations enacted well-established gender roles, which played with the elite culture of courtship and seduction, along with the sexual allusions connected to the vocabulary and gestures of electrical experiments.

Bose, who performed for the duchess of Gotha, designed an experiment that turned ladies into electric Venuses. For this demonstration, which he called “Venus electrificata” and which Franklin later renamed the “electric kiss,” a lady stood on an insulated stool while a gentleman tried to kiss her, only to receive painful sparks from her lips. Gentlemen, in their turn, could perform their virility by “inflaming spirits,” that is, setting fire to alcohol with electrified swords. For those who preferred a less aggressive model of masculinity, Bose designed an electric “beatification,” which made a luminous halo appear above a person’s head. Nollet’s celebrated “electric commotion,” an experiment where people holding hands experienced an instantaneous electric shock at the same time, borrowed bodily gestures from the cotillion, a dance popular at court and among the aristocracy. The first and most spectacular iteration of such demonstration took place in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the place for special balls, where Nollet invited one hundred eighty people to form a human chain. Not surprisingly, Haller commented in his article that electricity had “replaced the quadrille” in the social gatherings of the time.

Bose also introduced a gendered terminology into his theory of electric attractions and repulsions, which presented an innovative explanation of electrical phenomena based on the distinction between “male” and “female” electric fire. According to this theory, the male fire, emitted by metals and animal bodies, was strong and powerful, and sparks, with their crackling sound, were its visible manifestations. The female fire, on the other hand, was a weak luminous emanation, the kind of light that characterized the aurora borealis. The gendered roles participants were assigned at electrical soirées in which entire families took part turned the potentially indecorous effects of electrification into socially acceptable choreographies.

Electrical demonstrations took place for the most part in the dark and capitalized on the gallantry and innuendo that characterized eighteenth-century sociability. The gestures associated with electrical experiments—the rubbing of a long glass rod that emitted a stream of sparks or the gentle caressing of a globe—elicited the salacious curiosity of the salon goers and captivated the imagination of pornographers and satirists. Theories that connected the electric matter to the principle of life, together with the discovery of animal electricity later in the century, further excited the popular imagination. The Marquis de Sade was profoundly inspired by the violent bodily convulsions caused by the discharge of the Leyden jar and liberally employed electrical vocabulary in his works. The idea that electricity could be used to promote fertility was at the core of the Temple of Health and Hymen, the London extravaganza of the medico-electrical quack George Graham. Among its many prodigious treatments, the temple featured a “celestial bed” surrounded by electrical effluvia, where couples allegedly could successfully conceive. Authors who believed that the electric fire was connected to virility found short-lived confirmation in the rumor that the Leyden experiment did not work on the castrati. Although the rumor was unfounded, the very fact that it spread reveals the pervasiveness of the sexualized interpretations of electricity.

Adapted from In the Land of Marvels: Science, Fabricated Realities, and Industrial Espionage in the Age of the Grand Tour by Paola Bertucci. Copyright © 2023 by Paola Bertucci. Published with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.