It is true that we count successive moments of duration, and that, because of its relations with number, time at first seems to us to be a measurable magnitude, just like space. But there is here an important distinction to be made. I say, e.g., that a minute has just elapsed, and I mean by this that a pendulum, beating the seconds, has completed sixty oscillations. If I picture these sixty oscillations to myself all at once by a single mental perception, I exclude by hypothesis the idea of a succession. I do not think of sixty strokes which succeed one another, but of sixty points on a fixed line, each one of which symbolizes, so to speak, an oscillation of the pendulum.

If, on the other hand, I wish to picture these sixty oscillations in succession, but without altering the way they are produced in space, I shall be compelled to think of each oscillation to the exclusion of the recollection of the preceding one, for space has preserved no trace of it; but by doing so I shall condemn myself to remain forever in the present; I shall give up the attempt to think a succession or a duration. Now if, finally, I retain the recollection of the preceding oscillation together with the image of the present oscillation, one of two things will happen. Either I shall set the two images side by side, and we then fall back on our first hypothesis, or I shall perceive one in the other, each permeating the other and organizing themselves like the notes of a tune, so as to form what we shall call a continuous or qualitative multiplicity with no resemblance to number. I shall thus get the image of pure duration, but I shall have entirely got rid of the idea of a homogeneous medium or a measurable quantity. By carefully examining our consciousness we shall recognize that it proceeds in this way whenever it refrains from representing duration symbolically. When the regular oscillations of the pendulum make us sleepy, is it the last sound heard, the last movement perceived, which produces this effect? No, undoubtedly not, for why then should not the first have done the same? Is it the recollection of the preceding sounds or movements, set in juxtaposition to the last one? But this same recollection, if it is later on set in juxtaposition to a single sound or movement, will remain without effect. Hence we must admit that the sounds combined with one another and acted not by their quantity as quantity, but by the quality which their quantity exhibited, i.e., by the rhythmic organization of the whole.

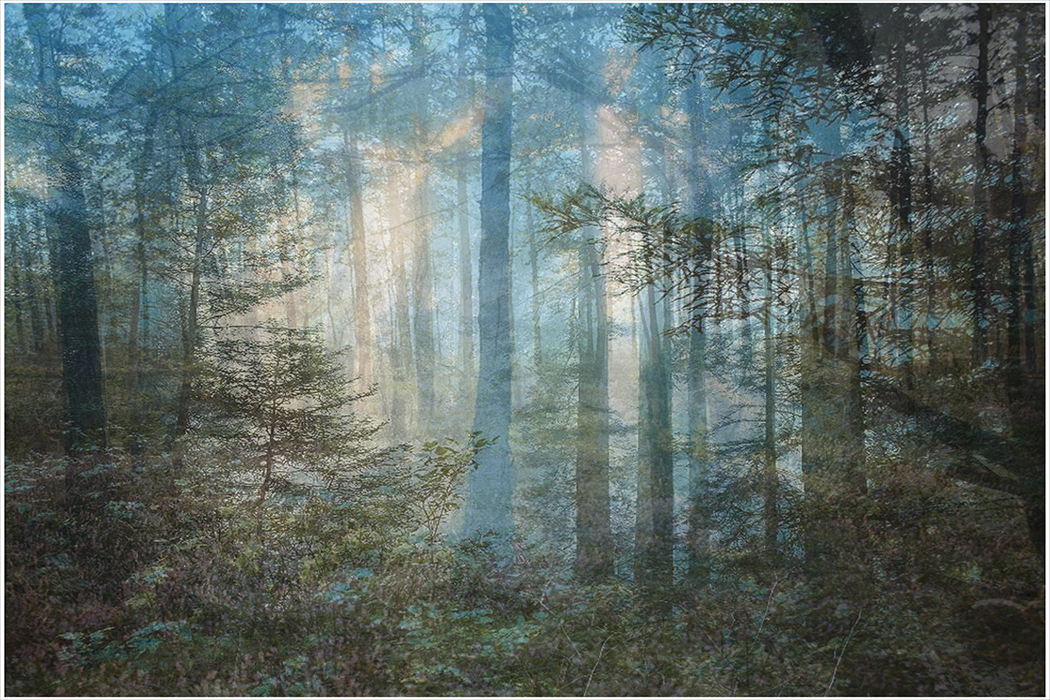

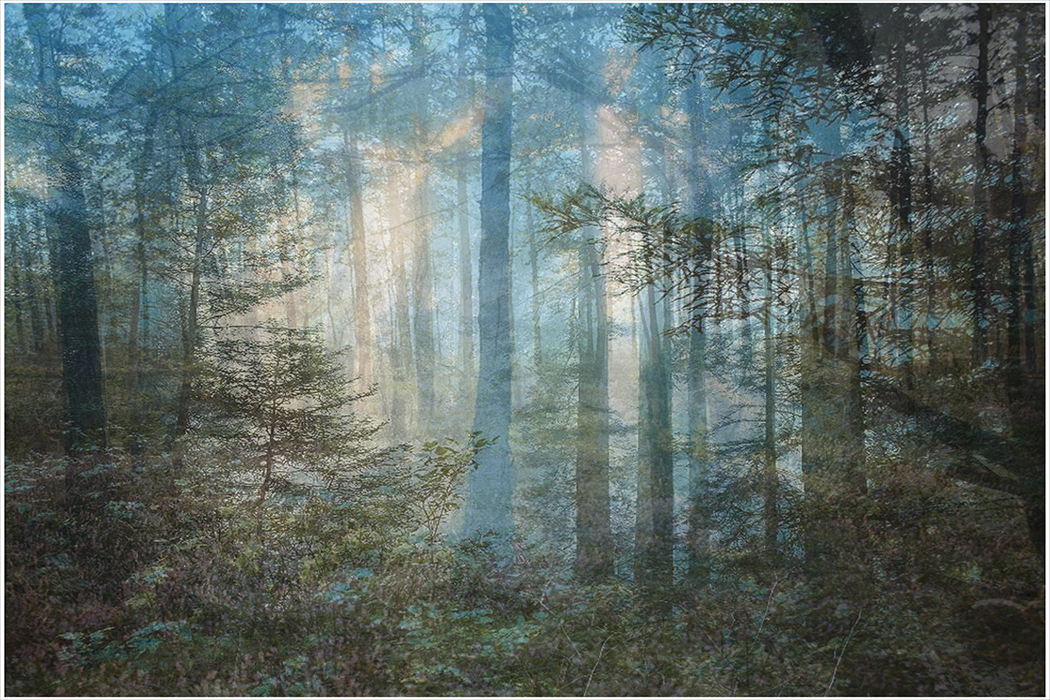

Four Years out of a Death Row Sentence (Forest), from the series Black Is the Day, Black Is the Night, by Amy Elkins, 2011. © Amy Elkins, courtesy of the artist.

Could the effect of a slight but continuous stimulation be understood in any other way? If the sensation remained always the same, it would continue to be indefinitely slight and indefinitely bearable. But the fact is that each increase of stimulation is taken up into the preceding stimulations, and that the whole produces on us the effect of a musical phrase which is constantly on the point of ending and constantly altered in its totality by the addition of some new note. If we assert that it is always the same sensation, the reason is that we are thinking not of the sensation itself but of its objective cause situated in space. We then set it out in space in its turn, and in place of an organism which develops, in place of changes which permeate one another, we perceive one and the same sensation stretching itself out lengthwise, so to speak, and setting itself in juxtaposition to itself without limit. Pure duration, that which consciousness perceives, must thus be reckoned among the so-called intensive magnitudes, if intensities can be called magnitudes: strictly speaking, however, it is not a quantity, and as soon as we try to measure it, we unwittingly replace it by space.

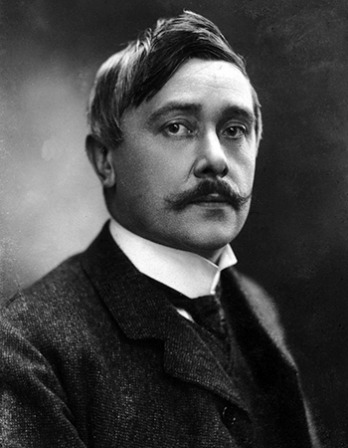

From Time and Free Will. This work was Bergson’s doctoral dissertation. In it he emphasized the importance of regarding time as an inner state of pure duration rather than as a measured quantity, its customary conception. His ongoing emphasis on inner experience came to influence novelists such as James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and Marcel Proust (who was the best man at Bergson’s wedding in 1891). Bergson published Matter and Memory in 1896 and Creative Evolution in 1907, and he received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1927.

Back to Issue