The boy is, of all wild beasts, the most difficult to manage.

—Plato, 348 BCPaths to Glory

Marie Bashkirtseff’s dramatic teenage diary.

Sunday, July 2

Oh, how hot it is! And how dull! No, I am wrong in calling it dull—one cannot be dull with so many mental resources as I have. I am not dull, because I can read, sing, paint, and muse to myself, but I am restless and depressed.

Is my poor youth to be spent between the dining room and petty domestic worries? A woman lives from sixteen to forty. I shudder at the thought of losing even a month of my life.

What is the good of my having studied, of having tried to know more than other women, of priding myself on knowing all the branches of learning that are attributed to famous men in their biographies?

I have some idea of them all, but I have only really gone into history, literature, and natural philosophy, so as to read everything about them—everything that is interesting. As a matter of fact, I find everything interesting that I put my heart into, and this sets me on fire.

What then is the good of my having studied and thought? Why endowed with wit, beauty, and a voice? To grow moldy, to be bored to death? If I were ignorant and coarse, perhaps I should be happy.

Not a single living soul to talk to! A girl of sixteen cannot be quite satisfied with the family circle, especially when she is a girl like me.

Of course Grandpapa is clever. But then he is old and blind, and he is everlastingly quarreling with his man and grumbling about the dinner.

Mama has plenty of esprit, but not much information; her manners are not polished, she hasn’t any tact, and her mind has got dull and rusty through her never talking about anything but the servants, my health, and the dogs.

Auntie is rather better. She even rather impresses you when you don’t know her well.

Have I ever mentioned their ages? Mama would still be a fine woman if it were not for her bad health. Auntie is a few years younger, but she looks the elder of the two. She is not good-looking, but tall and well proportioned.

I am going away tomorrow. I can’t say how sorry I am to leave Nice.

All these preparations for the journey rather damp my resolution.

I have selected the music to take with me, and some books, the encyclopedia, a volume each of Plato, Dante, Ariosto, and Shakespeare; also a number of English novels by Bulwer, Collins, and Dickens.

I was rude to Auntie, and then I went out on the terrace. I stopped out in the garden till dusk. How lovely the twilight is with the sea and space for background, and these luxuriant plants and thick-foliaged trees! And then, by way of contrast, the bamboos and palms. The fountain, the grotto with its little waterfall trickling from rock to rock before falling into the basin. All around, the bushy trees give the spot a look of peacefulness and mystery, which makes one lazy and sets one dreaming.

Why does water always make one dreamy?

I stopped in the garden and looked at a stone vase in which a lovely canna was just unfolding. I thought how pretty my white dress and leafy crown must look in that entrancing garden.

Is that all I am ever to do in life—dress myself carefully, put leaves in my hair, and think about the effect?

Well, candidly, if other people were to read me I think they would consider me a bore. I am still so young, I know so little of life!

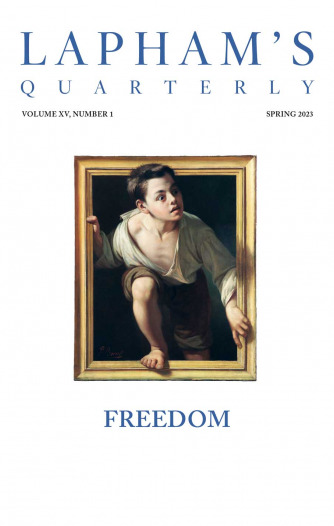

Fresco of boxing boys, Akrotiri, Greece, sixteenth century BC. National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece.

I cannot speak with the authority or the assurance of writers who profess—what presumption!—to know men, to lay down laws and to bind their maxims on other people.

My maid is here with a dress for me to wear tomorrow; it reminds me of my departure.

I went back to my room, followed by all the dogs. I drew my white trunk close to the table. Ah, my chief regret!…my diary…It is part of myself. Every day I have been in the habit of running through the pages of one of my manuscript books when I wished to recall Rome or Nice, or something older still!

When people talk of glory, soul, or beauty, they are only talking of love. They only talk of glory and beauty in order to make a fittingly handsome frame for that picture which is always the same yet ever new.

The idea of leaving my diary here hurts me.

Poor diary, it contains all my strivings toward the light, all those aspirations that would be considered those of an imprisoned genius if they were crowned in the end with success. If, on the other hand, I never come to anything, they will be looked upon as the conceited ravings of a commonplace person.

To marry and have children! Any washerwoman can do that.

Unless I could find a civilized and enlightened man, or one who is pliant and very much in love.

What do I want? Oh, you know well enough. I want glory.

Marie Bashkirtseff

From her journal. A year after making this entry, Bashkirtseff at the age of eighteen wrote, “To die!!!! Without leaving anything behind me? To die like a dog! Just as a hundred thousand women have died, whose names are barely inscribed on their tombstones…God wills that I should renounce everything and give myself up entirely to art.” She exhibited paintings at the Paris Salon for the first time in 1880 and four years later died of tuberculosis. Her journals were published in 1887, prompting British prime minister William Gladstone to call the author a “true genius.”