A righteous man regardeth the life of his beast.

—The Bible,

Autumn River in the Rain and Clouds, formerly attributed to Xu Daoning, sixteenth century. Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Asian Art, Freer Gallery of Art, gift of Charles Lang Freer.

Geology is in all senses a more solid intellectual exercise than most, and when it comes to imagining truly plausible geological counterfactuals—what tectonically realistic what-ifs could have shifted the four-billion-year course of the planet’s history—it becomes quite clear that the possibilities are really rather limited. By comparison with earth scientists, historians have it easy: it is perfectly simple to imagine, for instance, the cascade of consequences that might follow if Hitler had sipped chamomile tea instead of a double espresso on a certain afternoon at Berchtesgaden; or, more recently, if the American secretary of defense had broken his neck instead of his arm when he tripped on the curb of his Chevy Chase driveway. In history all is plausible, so all is possible.

The earth, however, does not permit such flexible imaginings. One cannot realistically suppose a volcano erupting in Manhattan; and it would be difficult to persuade any reputable geophysicist that the Atlantic Ocean could be ten thousand miles wide instead of its present three. The hard facts of the earth’s equally hard surface circumscribe such fancies. Even in those areas where some imaginings can reasonably occur—what if the Bering Strait had never closed, or what if the English Channel had never opened, both of which are within the realm of the geologically possible—the imagined effects are generally rather limited too.

Then again, contemplating the development of Britain as a peninsular rather than an insular nation is, perhaps, a little more likely to yield some interesting scenarios. The English like to believe their uniqueness derives from the maritime barrier that stands between them and France. But it is perfectly reasonable to argue otherwise. It is just as likely that Britain’s remarkable genetic mélange has mattered most and that geology has been less important than any soliloquy about scepter’d isles and precious jewels set in silver seas would have us believe.

In a far corner of the world, however, there is one geological possibility—a very reasonable, very plausible one at that—which, had it been exercised about forty million years ago by the planet’s subterranean engine, would have changed just about everything. And that is the imagined shift, by just a few hundred yards, of a small and insignificant-looking mountain that rises two thousand feet from within a flower-filled valley in the southern part of the Chinese province of Yunnan. If Cloud Mountain, as it is locally known, had been only half a mile from where it currently stands then the entire world would be a very, very different place.

It all has to do with the Yangtze River and with a geological configuration known all across China as the Great Bend.

Five of the noblest rivers in the Eastern world have their beginnings at an altitude of over fifteen thousand feet in the soggy grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau. To get around the Himalayas all five of them first swing to the east, although one of their number, the Brahmaputra, turns swiftly south to wander through the lowlands of Bengal. The other four, however, turn rather more lazily in tandem. Indeed, they all run alarmingly close to one another and in parallel like two sets of railroad tracks.

Eventually, the Irrawaddy peels off toward western Burma, while the remaining trio—the Salween, the Mekong, the Yangtze—travel for a long and topographically unprecedented stretch. They rush due south in adjoining valleys not thirty miles apart. All keep their relentlessly identical direction. The Salween spears its way down toward Rangoon. The Mekong barrels its way into the jungles of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. And the Yangtze—it is worth mentioning that the Chinese do not know it by its British-given name, but as Chang Jiang, Long River—would do the same. But after nine hundred miles of unyielding southerly progress, the river reaches the point where it suddenly collides, head-on, with the utterly unexpected protrusion of Cloud Mountain.

You can see just what happens if you stroll up through the laneways of Shigu Town nearby and climb up the mountainside—brushing through the groves of rhododendron bushes, ducking under the camellias and the stunted camphor trees, until reaching the summit where the grasses fold aimlessly in the warm breeze and cows graze amiably. The mountain seems vaguely out of place. All of the other blue-hazed hills have ridges that trend north and south, lined into the distance in serried ranks, arrayed like soldiers in formation; but this modest hill is like a renegade flank standing athwart the pattern, its shape elongated toward the east and the west. If you stand atop the hill and look north by northwest, the effect of this difference becomes clear immediately.

Ahead is the unmistakable winding-sheet of the Yangtze: six hundred feet wide, furious with power, rushing down through an arrow-straight declivity that seems to reach all the visible way back to the blue Tibetan Hills. Closer and closer it comes, straight and true, and then quite suddenly, the stream plows into the mountain’s base with an enormous and perpetual thudding sound. The cannonade is so powerful—the river slamming so fiercely into the cliffs—that one can fancy the rocks quivering under the endless force of the water. The vast brown stream comes instantly alive with an array of currents and boils and white-rimmed rips—and then, just as quickly, the entire river bounces off the rockwalls and hurtles back northward again.

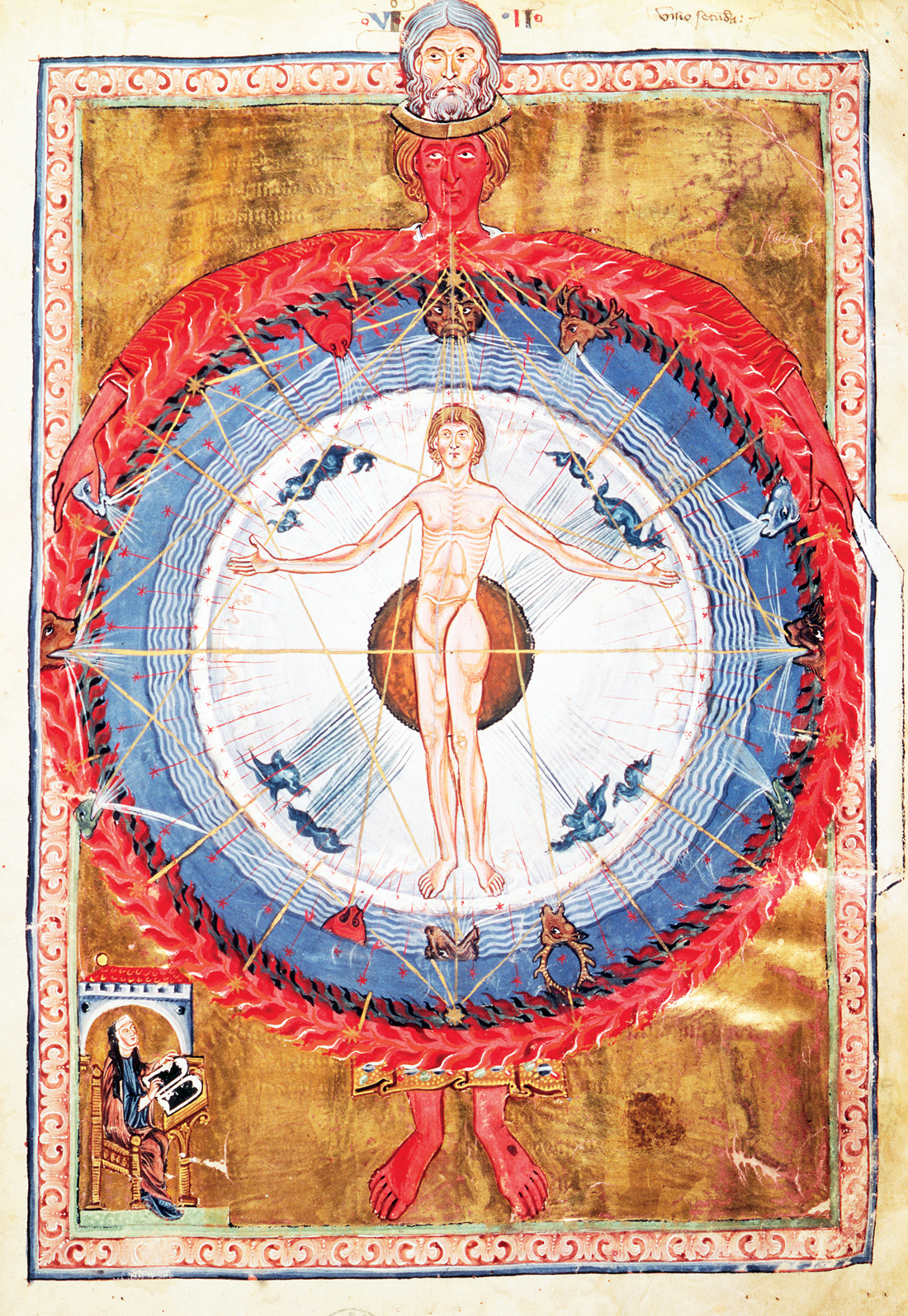

Man as the center of the universe, illustration from De Operatione Dei, by Saint Hildegard of Bingen, c. 1200. Biblioteca Statale, Lucca, Italy.

It gets to go there solely by virtue of what China now calls the Great Bend—the biggest bend that any great river anywhere in the world makes, an extraordinary turn-on-a-dime, whirl-on-a-sixpence, now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t kind of riverine backflip that is visible on even the smallest-scale maps. A nautical compass will show how much of a paperclip-like hairpin it executes: it roars into the bend southbound on a heading of 190 degrees and thrusts northward on a heading of 25 degrees—in just a hundred feet or so completing a swing of 165 degrees, almost, in other words, backtracking along its own path. Free of the geological obstacle, the Yangtze then gathers up its skirts and dances off to the northeast into a maelstrom of white water that has lately become world-famous: the Tiger-Leaping Gorge, one of China’s answers to the Grand Canyon.

From the Gorge the river then heads roughly eastward for three thousand miles—passing first into Sichuan, washing its way past Chongqing (now by some counts the world’s biggest city), on through the ocher-earthed granary that is known as China’s “red heart.” It next pours its waters into the 244-square-mile lake that has been created by the gigantic Three Gorges Dam begun in 1994. After this grim pause, the river, ever muddier and thicker, continues down toward the cities of Wuhan and Nanjing. By now it is laden with millions of tons of silt and polluted by a foul witches’ brew of chemical and heavy industrial metals. The river’s fish and its few remaining mammals, such as the charming pink-skinned Yangtze dolphin, are mostly dying and rotting by its oily shores. Finally, weary and slow, the river oozes out into the East China Sea through the gigantic and garish dream city of Shanghai. By the time it reaches the sea, the river will have traversed almost four thousand miles of land—a thousand miles south, then three thousand miles east—and descended sixteen thousand feet of altitude.

But not one single mile of its relentless eastward downflow would ever have happened had Cloud Mountain not given the river its almighty shove toward the east at Shigu Town. A glance at any topographical map will show exactly what would have occurred instead. Just like the Mekong and the Salween, the Yangtze would have continued to thrust its way south. It would have merged with a tributary called the Yuan River in southern Yunnan, crossed the border into Vietnam, swept grandly through the city of Hanoi, and finally entered the ocean in the Gulf of Tonkin. It would have enjoyed a total length of around fifteen hundred miles. It would have been a great river, true, but not very different in either aspect or effect from any of the other immense streams that flow into the sea between Calcutta and Hong Kong.

And it could have happened. Research published in 2002 by a Beijing geophysicist named Zeng Pusheng has shown incontrovertibly that it was a sudden eruption of Eocene volcanoes, around forty-two million years ago, that pushed lava out in front of the stream where Cloud Mountain now stands and promptly created an immense upriver lake. At the same time pressure from the ever-rising Himalayas lifted this lake up and up, tilting the landscape upward from the west to a point where the waters could only spill out eastward—which they finally did, escaping in an unimaginably fierce torrent that carved its way majestically through the Tiger Leaping Gorge and eventually out into the center of China.

Here then is the eminently plausible what-if. For it is entirely possible that this small Eocene volcano could have erupted as little as a mile from where it did. Had it done so, thereby leaving the passage of the proto-Yangtze unblocked, the river would have been quite unable to avoid the fate of its neighboring streams and would have wound south to Hanoi. Such a counterfactual falls readily within the realm of the geologically believable. And had it happened, the consequences would be utterly profound.

For without the Yangtze, there would be, quite simply, no China.

Such an impact on the building of nations can be said of very few rivers in the world. It is entirely reasonable, for instance, to imagine France without the Seine, the United Kingdom without the Thames, Brazil without the Amazon. It is even arguable that there could be America without the Mississippi. The countries would all be the poorer for the absences, but not devastatingly so.

There are, however, a few rivers that are so central to the birth of a nation, are so much keystones of national identity or economy, that it is difficult to imagine the one without the other. Egypt without the Nile, to take an obvious instance, would simply not be Egypt—it would in almost all certainty be dusty and barren, and thus likely uninhabited, a mere extension of the Sinai or the Western desert. No Abu Simbel. No Karnak. No Saqqara and certainly no Sphinx or pyramids at Giza. Then again, an India with neither the Indus nor the Ganges would be the palest shadow of herself, probably no more than a satrapy of Persia.

China without the Yangtze would be similarly reduced—probably even more so. Her northern part might survive as a distinct entity, confined by the valley of the Yellow River, but her south, her west, and most tellingly of all, her east, would all lie riverless—a series of wildernesses stifled in disparate and unarable confusion.

It is not just a question of reduction. A Yangtze-less China would not be China at all, and there are two reasons why.

The first is a simple matter of the life and death of those who live beside it. The Yangtze provides in sufficient abundance nutrient-rich water and a means of transport to support a population that is now almost as big as America and Western Europe combined—nearly half a billion people crammed into one almighty watershed. All other southern Chinese rivers save two flow into the Yangtze and all crops are watered by her. All the trading barges, the sampans, the passenger ferries, and the junks (and since the beginning of the last century, all of southern China’s powered boats) use the Yangtze as their principal interprovincial highway. The hundreds of millions who live between Chengdu and the east coast rely completely for produce grown in the fields watered by the Yangtze. To get this produce to them, or to get whatever they make to their customers, they rely on the boats that travel on the natural highway it provides. With no Yangtze there would be no practicable means of shipping coal or ore or hay or stone; there would be no water and no irrigation, and if not this, then no rice, wheat, sorghum, or soy. China’s Red Basin, today as fertile as Kansas, would be, sans Yangtze, as dry as Mongolia. The entirety of southern China would only be capable of supporting a population of nomads, wandering men answerable to no one, paying fealty to no central authority.

The second set of reasons concerns that very authority. It remains a fact that centralized command in China was established initially, and perhaps surprisingly, for one overarching reason: to exercise control over the annual and devastating flooding of the Yangtze, the one critical natural phenomenon that had long plagued the fledgling country.

Topographic and climatic realities ensure that every spring the Himalayan and Tibetan snowmelts cause the headwaters of the Yangtze to swell enormously. By the time the rolling waves of water reach the Red Basin, another environmental factor enters into the equation: the southwest monsoon sweeps in from the sea, dumping untold quantities of rain into the swelling rivers. The results are invariably spectacular, often catastrophic. The river floods, tears down villages, destroys bridges, and drowns thousands. It has been happening for scores of centuries; it is a problem that has never been properly solved. The construction of the Three Gorges Dam is one of the devices by which modern technology hopes to do so. Such an ambitious project was unsurprisingly supported by Chairman Mao, who wrote in 1956: “Walls of stone will stand upstream to the west… / Till a smooth lake rises in the narrow Gorges.” The dam is scheduled to provide 10 percent of China’s electrical needs—the same output of ten to twenty coal-burning stations—but Mao didn’t anticipate his dam would be so ill-built, nor perhaps did he care that millions of people would face the same prospect of basin-flooding: not natural and seasonal this time, but state-sanctioned and permanent.

The Peaceable Kingdom and Penn’s Treaty, by Edward Hicks, 1829–1830. Yale University Art Gallery, Bequest of Robert W. Carle, B.A. 1897.

The regular summertime Yangtze flooding created the stimulus for a development in ancient China that has endured like little else: a supranational bureaucracy. Wise ancients realized that the problems caused by a wayward river, rolling as it does from one region to another, could never be addressed adequately by regional authorities alone. A transnational body would have to be created to meet the challenges of a river that is a truly transnational entity. And so, some four thousand years ago, an emperor named Da Yü—Yü the Great, a legendary figure still revered today, a heroic visionary who assumed the duty of harnessing and taming his country’s wilder streams—took the first steps.

According to myth, Yü built cofferdams, dug spillways, carved diversion channels, and, crucially, helped establish the first all-China bureaucracy both to manage the construction and deal with the country’s yearly flooding problems. With this bureaucracy there came government, and with this there came consistent rule, and law, and sets of shared goals. In time, these processes led to the unification of all of China. Out of the great mass of confusions that is known to historians as the Warring States Period came a united China.

The initial creation of China was, in other words, the consequence of a direct intellectual and physical response to the caprices of a river—and a river that might, in short, have never existed. If the volcano at Shigu Town erupted just half a mile or so to the west of where Cloud Mountain now rises so prettily, the Yangtze would have gone elsewhere. But for a few hundred yards of tectonic randomness, the world’s oldest civilization might never have been created, and the country that is surely about to become the world’s richest, grandest, and most powerful might never have even been born.